4 Brass Acoustics

Brass instruments are all built on a shared set of acoustical principles. These principles make it that concepts learned on one instrument transfer to all other brass instruments. If you can develop your familiarity with these underlying principles, your movement between instruments as a performer and a teacher will be greatly simplified.

Overtone series

All musical sounds make use of a fixed overtone series which is dictated by physics. These overtones become apparent on non-brass instruments as well in particular situations, such as the altissimo register on single reed instruments and harmonics on strings. The particular combination of overtones with varying degrees of prominence is also what gives each instrument its unique timbre. A great illustration of these overtones can be heard if you play a note on any instrument directly into an undampered grand piano. The strings of the piano will sympathetically resonate the present overtones, creating a harmonic echo of the instrument that was played.

For all musical sounds, the overtone series is fixed based on sound wave ratios. Every time the length of a sound wave is cut in half, our ear perceives the difference of an octave between any two pitches. So to use a commonly referenced pitch, A440 is the A above middle C (aka a4). A220 is one octave lower, the A below middle C (aka a3). A880 is the A above the treble clef staff (aka a5). Similar ratios exist for every harmonic interval. A quick Google search for “Harmonic Series Ratios” will give you a much more scientific and detailed explanation than will be provided here for the curious!

So what does this mean for brass instruments? As you have already noticed, there are only 3 valves on most brass instruments (or seven slide positions for the trombone). There are obviously well more than seven notes that can be played on a brass instrument, and this is done through the manipulation of the overtone series.

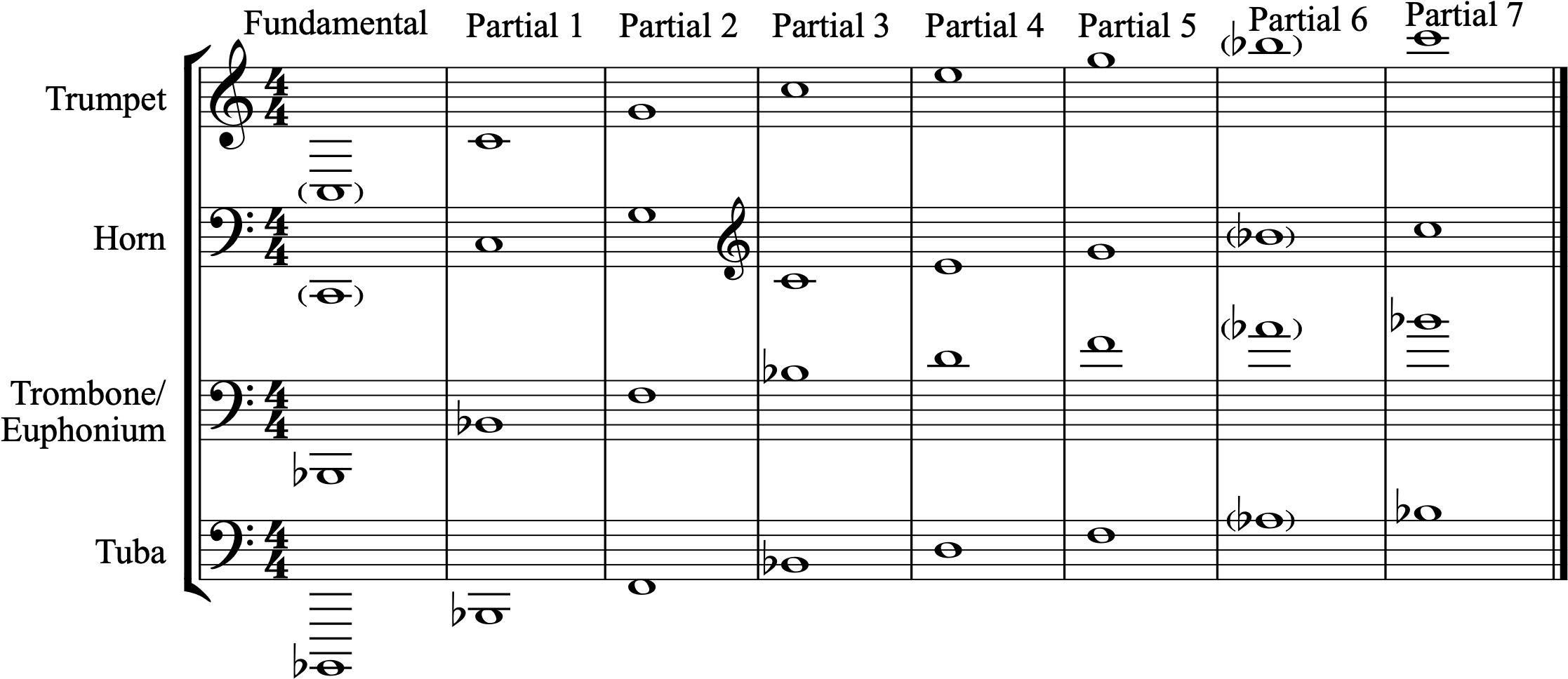

On any fingering combination, a sequence of partials can be played. Partials are the presentation of the various overtones as the primary overtone on a brass instrument. You may also hear brass players refer to shelves, which is a slang reference to brass partials. Each brass instrument has a fundamental pitch, which is the hypothetically lowest note in open fingering (or first position for trombone), as shown in the chart below. For some brass instruments, particularly the trumpet, this pitch is not usable due to the acoustical construction of the instrument which distorts the timbre in that register. With that said, this fundamental is regularly used in advance literature for various instruments including horn, bass trombone, and tuba.

Brass Instrument Fundamentals

Notes in parentheses are functionally unusable due to tone or intonation

Above that fundamental, open fingers follow the same pattern.

| Partial | Change from previous partial | Change from fundamental |

| Fundamental | ||

| 1st partial | Perfect 8 | 1 Octave |

| 2nd partial | Perfect 5 | 1 Octave + Perfect 5 |

| 3rd partial | Perfect 4 | 2 octaves |

| 4th partial | Major 3 | 2 octaves + Major 3 |

| 5th partial | minor 3 | 2 octaves + Perfect 5 |

| 6th partial | flat minor 3 | 2 octaves + flat minor 7 |

| 7th partial | sharp Major 2 | 3 octaves |

Hypothetically, this pattern continues infinitely with increasingly smaller intervals between notes. For musicians that perform advanced literature that continues into that upper register, individuals will frequently identify the easiest fingering combinations and partials to use for various notes. Historically, there was also literature written that utilized this extreme upper register, such as diatonic trumpet music of the Baroque period.

As shown in the chart below which presents the most common brass instruments, once the fundamental pitch is established, it becomes easy to identify the various partials using the series of intervals. Each partial also has characteristic tuning problems. Octaves of the fundamental are always in tune, but the other partials need to be adjusted through the embouchure to ensure that they are played in tune. Notably, the 6th partial is so flat that it is functionally unusable.

| Partial | Intonation tendency |

| Fundamental | in tune |

| 1st partial | in tune |

| 2nd partial | 2 cents sharp |

| 3rd partial | in tune |

| 4th partial | 14 cents flat |

| 5th partial | 2 cents sharp |

| 6th partial | 31 cents flat (functionally unusable) |

| 7th partial | in tune |

Valve acoustics

The valves on all brass instruments are developed the same way, allowing for the transfer of fingering concepts across brass instruments. The role of each valve stays the same between brass instruments, and the same sequence of combinations is used as it relates to the partials. Once you learn valve sequences on one brass instrument, you can transfer those ideas across instruments.

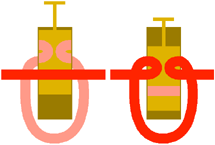

Whether a valve, a rotor, or a slide, the underlying function remains the same. When the valve or rotor is depressed or the slide is moved out, additional tubing is added to the instrument by the additional channels that are opened in the valve or rotor. By adding additional tubing, the pitch on the instrument moves flat.

When pressed down, valves and rotors open additional tubing for air to move through, thereby making the pitch flat.

All brass instruments aside for trombone have three valves or rotors, and many are augmented with 4th valves (and in the case of tuba, occasionally 5th and 6th rotors). Valves, rotors, and trombone slides are mechanically different, but their function is the same: to open up additional tubing for air to move through. By adding tubing to the brass instrument, the instrument becomes longer, which results in a lowered pitch. The role of each valve/rotor is as follows:

1st valve-lowers Major 2nd

2nd valve-lowers minor 2nd

3rd valve-lowers minor 3rd

4th valve-lowers perfect 4th (found on piccolo trumpet, higher quality euphonium, and many tubas)

5th valve-lowers flat Major 2nd (found on advanced tubas in some keys)

6th valve-lowers flat minor 2nd (found on advanced tubas in some keys)

The horn additionally has a unique system that creates two instruments in one. The so called “trigger” on double horns opens a second set of tubing that is pitched a perfect fourth higher from F to Bb which provides a different set of fingering combinations and allow for greater ease in certain registers.

When learning valve combinations, the same sequences are used to produce chromatic notes as they relate to the fundamental. Because the partials on brass instruments become closer together the higher the register is, many pitches have multiple fingerings that can be functionally used. In general, the preferred fingering is the one positioned higher up on the chart below, as the intonation issues become more pronounced lower down on the chart. The other available fingerings become alternates that can be used in rare occasions such as trills, complicated technical passages, and corrections to particularly out of tune upper partials. You will notice that the 1st and 2nd valves on their own are naturally slightly flat and the 3rd valve is unusably flat. This is to accommodate fingering combinations with them that become sharper.

Valve combination |

Chromatic change down |

Intonation tendency |

| 0 (no valves) | Unaltered partial | In tune |

| 2 | minor 2nd | 5 cents flat |

| 1 | Major 2nd | 5 cents flat |

| 1-2 | minor 3rd | 1 cent sharp |

| (3) | minor 3r d (unusable) | 21 cents flat |

| 2-3 | Major 3rd | 8 cents flat |

| 1-3 | Perfect 4th | 7 cents sharp |

| 1-2-3 | Augmented 4th | 28 cents sharp |

Different fingerings or other techniques are used to allow for the correction of the innate intonation problems of various fingerings, which will be discussed in the chapters on individual instruments. Pertinent at the moment, the 4th valve found on many euphoniums, tubas, and specialty trumpets serves a specific purpose as a more in tune alternate to 1-3 combinations. 4 can be used in place of 1-3 to play a perfect 4th and 2-4 in place of 1-2-3. It also allows the player to close the gap created between the fundamental and first partial, functionally extending the range of low brass instruments.

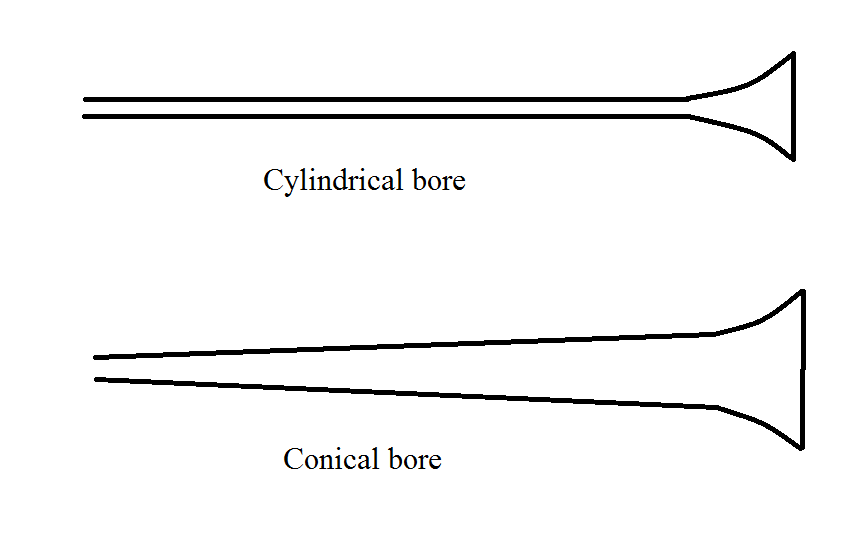

Conical versus Cylindrical Construction

The acoustic design of brass instruments affects their overall timbre as well as aspects of individual instruments’ technical performance. The primary distinction deals with the construction of bore (diameter) of the tubing which come in two variations:

The bore gradually increased in diameter from the mouthpiece through the bell flare. The resultant timbre is typically warmer and less direct. A conical bore instrument will require more air than a similarly sized cylindrical bore instrument but will typically have a smaller mouthpiece that is more responsive to pitch adjustment.

The bore stays the same from the mouthpiece to the flare of the bell. The timbre tends to be very direct and bright. The mouthpiece will be wider than a similar conical instrument but will be more temperamental to embouchure changes in regard to timbre.

While there are no standard brass instruments that are purely cylindrical or conical, brass instruments are typically grouped around these tendencies. Instruments with cylindrical tendencies include trumpet, trombone, baritone, and sousaphone. Instruments with conical tendencies are horn, euphonium, tuba, cornet, and flugelhorn.

Familiarity with these characteristics can help teachers understand issues that students encounter. Beginner students on conical instruments need to focus on rich tone development and may have issues centering pitch. These instruments also require more air than similarly sized cylindrical instruments, requiring a more relaxed embouchure that allows for free buzzing. Depending on construction, valve/rotor slides may not be reversible, so students should take care to place slides back into the instrument with correctly matched tubing bores.

Beginner students on cylindrical instruments will find that fatigue sets in more quickly and need to be aware of the potentially strident tone that they often create. Their embouchure needs to be more focused and firm than students on similarly sized conical instruments as well.

Transposition and Notation

Similar to clarinets and saxophones, brass instruments are pitched in different keys. The pitching of brass instruments refers specifically to the position of the fundamental pitch of the instrument. Instrument names refer to the concert pitch which sounds when playing the lowest fundamental partial. This system dates back to when brass instruments were without valves, rotors, slides, or keys to allow for chromatic performance. As pieces were written in different keys, crooks needed to be added to the instruments to allow them to play the most typical notes in each key. As chromatic additions were made to brass instruments, various keys became preferred for each instrument. Common keys for each instrument are listed below.

| Instrument | Most common key(s) | Additional keys |

| Trumpet | Bb, C (orchestral) | Eb, D |

| Horn | F | Eb, Bb |

| Trombone | Bb | |

| Euphonium | Bb | |

| Tuba | BBb, CC (orchestral) | Eb, F |

Brass Notation

The notation of brass instruments is not consistent in how it addresses keyed instruments. Treble and bass clef notations differ.

Treble Clef Instruments

Trumpet and horn parts are typically written to reflect instrument pitch, as opposed to concert pitch. This allows for transferability across different keyed instruments. On these instruments, the pitch C represents the instrument’s fundamental, regardless of concert pitch. So, on a Bb trumpet, the written C is concert Bb. Similarly, on an F horn, the written C is a concert F.

The general rule of thumb for transposing instruments is that the written pitch is written higher than the concert pitch. so for the Bb trumpet, the transposition from concert pitch to written pitch is a Major 2nd up. For the F horn, the transposition from concert pitch to written pitch is a Perfect 5th up.

The benefit of this system of notation is that students can easily move between instruments that are pitched differently. A trumpet player will play a written F with the first valve regardless of whether they play on a Bb, C, or Eb trumpet (provided the part is written for that instrument). The disadvantage is that the player must know what their written pitch transposes to in concert pitch to communicate with other musicians.

Bass Clef Instruments

Bass clef brass parts are typically written to reflect concert pitch, regardless of the key of the instrument on which the part is being played. The Bb that is written for a trombone, euphonium, or tuba is a concert Bb. If the musician is playing on an instrument that is not pitched in Bb (for example, a CC tuba), the fingering combinations change, forcing them to transpose the part to perform it.

The benefit of this system is that bass clef musicians speak the same key language as the rest of the ensemble. An F on the trombone is the same as the F on the piano. The disadvantage is for musicians when they become more advanced and move between instruments that are pitched in different keys. They must make sure to be aware of the key of their instrument, and properly transpose fingerings to match the transposition.

Euphonium BC/TC

The euphonium (or baritone) pose a unique challenge, in that parts for bands are often written for both bass clef (BC) and treble clef (TC). The parts are typically identical in performance, but are notated differently. Euphonium TC follows the tradition of notating C as the fundamental, making it a transposing instrument. Euphonium BC is notated in concert pitch. So while the sound created would be the same, Euphonium TC would have a C notated at the same time as Euphonium BC would have a Bb notated, matching concert pitch. This notational practice is due to the frequency of having trumpet players switch to euphonium or baritone. The notation of Euphonium TC parts eliminated the student’s need to relearn fingerings and clef in the transition to a new instrument.