3 Screens, Spins, and Perceptions of “Reality”

We are living in the information age, characterized by our digital communication tools and our constant and instantaneous access to information. Ironically, that doesn’t always mean we’re more informed. Surely, you’ve learned by now that just because you read something on the internet doesn’t mean it is true. Digital literacy is largely about learning how to navigate through the infinite amount of information online—full of agendas, spins, willful ignorance, and outright lies—to find the answers you’re looking for and to discern what information is credible and what isn’t.

The downside of the web’s infinite capacity for information sharing is just that. It’s infinite, and anybody can contribute. There is no gatekeeper or quality control specialist who makes sure that information posted on the internet is accurate. A Forbes article published in 2003 reported that roughly 53% of Americans believe that the internet is “reliable and accurate” (“For 53%”). Mind you, that was before the iPhone was invented, before it was common to have constant access to the internet through our phones and other handheld devices. Even then, as the article reports, internet use among average Americans was climbing, while their confidence in online information was on the decline.

Now compare those findings with a more recent Gallup poll from 2018. This survey is a little more complex, as it doesn’t lump all online information into a single category. Instead, it focuses more specifically on Americans’ perception of the news media, reporting that 62% of respondents believe that much of the news they receive from traditional sources (television, newspaper, radio) is biased, inaccurate, and purposely misleading (Jones). Respondents were even more skeptical of the news they encountered online or on social media.

As the Gallup poll suggests, there are reasons to be wary of information you encounter online, particularly in our current political environment in which people are quick to latch onto articles and studies that seem to validate their existing beliefs while people on the other side of the aisle are quick to label it as “fake news” (University of Michigan Library). Even more complex are the screens and biases that we bring to a message, drawing from personal experiences and our unique ways of seeing and thinking, which impact how we interpret that information. As many theorists argue, the meaning of a message isn’t inherent in the text itself; meaning is always found in the interpretation(s) of the receiver(s), which may or may not align with the intention of the sender.

Clearly, discerning “fact” from “fake news” is tricky business, especially in the digital realm where there is so much contradictory information, and it’s sometimes difficult to know who authored (or better yet, who sponsored) the information being presented. In some instances, digital messages lack the rich details—nonverbal nuances like body language, facial expression, tone, and so on—that help us interpret a message. At other times, digital tools make it possible to enhance or completely fabricate those same details. The goal of this chapter is to dive into some of those complexities to provide a deeper, more nuanced understanding of “truth”—both in general and online. We’ll also look at tools you can use to verify the information you encounter online and to guard yourself against the “fake news” that you might encounter.

Learning Objectives

- Consider the existence of multiple realities based on individual experiences and personal lenses for seeing the world.

- Understand the limitations of language and the importance of listening and seeking to understand the perspectives of others.

- Gain insight into how knowledge and our certainty of reality develop.

- Gain a deeper understanding of the political spins and biases that pervade the news media and provide different versions of the truth.

- Consider the prevalence and underlying agendas of fake news.

- Consider the dangers of the echo chamber.

- Learn how to distinguish fake news, gauge source credibility, and assess your own underlying biases and attitudes that might distort the way you receive information.

Terministic Screens and Perceptions of Reality

Have you ever walked away from a conversation with a friend, feeling like it was a really positive encounter, only to discover later that your friend was upset by something that was said? It’s a common phenomenon. Here’s a more specific example to demonstrate the point: Let’s say you pass one of your friends on the sidewalk. You’re in a rush to get where you’re going, so you don’t stop to chat. Instead you give a little wave and say, “I’ll talk to you later!” In your mind, perhaps, that was a positive exchange. You acknowledged your friend and made plans to catch up some other time. But your friend has a different impression. Maybe they just left a job interview that didn’t go well, and they’re already feeling down. Or maybe, their date for tonight just canceled on them, and they’re already feeling rejected. So to your friend, your quick greeting seemed halfhearted and insincere.

Misunderstandings are just that easy. Actually, they are even more prevalent when the message gets more complex and when we are communicating with people we don’t know or who are different from us in a significant way. That’s because all communication—both verbal and nonverbal—is subject to our individual interpretation. Every message has a text or a symbol—the thing that is actually said or the nonverbal cue that is displayed. In the above example, it’s the wave and the phrase, “I’ll talk to you later!” It’s the part of the message that you observe that is clearly true because everyone else can observe it, too. All the other bystanders on the sidewalk, for instance, would agree that you said, “I’ll talk to you later!” It’s a fact. They would also probably agree that “talk to you later” literally means that you plan to communicate with your friend again in the future. The denotation, or the literal meaning of a text or symbol, also tends to be fairly obvious to everyone involved, though not always.

Things get tricky when you interpret what is said—the implied meaning. In other words, the person sending this message has a purpose, a meaning that they intend for you to receive based on their selection of symbols. But it is up to you to encode the message to arrive at that same shared meaning. All too often, we don’t receive information the way that it was intended, and we arrive at a different meaning. To you, your greeting to your friend on the street meant “I care about you, but I’m too busy to talk right now.” To your friend, it meant “I don’t care about you that much. You’re not a priority.” Even more concerning is that if you don’t clear up the misunderstanding, your friend will accept it as fact that you aren’t as good of friends as they thought, and it will probably create a lot more misunderstandings in the future.

A good way to think about the way we interpret information is a term coined by Kenneth Burke in 1966 called our terministic screen (Stob). Burke was a philosopher and rhetorical theorist responsible for developing a deeper understanding of how people use language and the social effect that usage has. According to Burke, reality isn’t something that is stable or fixed. It’s in constant flux, varying from one person to another depending on their terministic screen, or the lens they use to process information. Put another way, your terministic screen is your way of seeing and thinking about the world, and it develops over time based on a complicated web of experiences and relationships. In Burke’s words, a terministic screen is “a screen composed of terms through which humans perceive the world, and that direct attention away from some interpretations and toward others.” Factors such as gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, family structure, socioeconomic status, existing beliefs, and personal biases have a complex and fundamental effect on the way that we view the world and how we receive new information.

Burke also references our use of selection, based on our terministic screen, when we send and receive information. Language is always a selection. When we describe an event, for example, it would be impossible to share every single detail about that event. We would select details that we think are important to the meaning of that event, and we would select words that we think most accurately capture those details. And by default, if we are selecting details and words to craft a message, we are automatically deselecting other details and words that don’t align with our perspective. Maybe you’ve heard people make the argument that language is never neutral or objective. This is what they mean. All language is a selection based on individual values and perspectives.

By the same token, when we receive information, we are also selecting details we think are most important to the overall meaning, which is why you and a friend could read the same book or watch the same movie and come away with different ideas about the overall theme. The more dissimilar your background is, the more likely it is that you will make different selections and form different interpretations. It’s like that movie What Women Want, in which Mel Gibson’s character is suddenly given the ability to read women’s minds. He is confronted with the stark contrast between how he and the women around him interpret information based on their lived experiences and personal values, and over time, he begins to see things through their lens a little more clearly. Admittedly, it’s an oversimplification of terministic screens, which are complex accumulations of all of our lived experiences and aspects of our identities, but it brings home the point about perspective.

Similar to Burke’s concept of terministic screens are two related theories that will deepen our understanding of “interpretation”—sociocultural theory and social constructivist theory. Both theories emphasize the way that meaning is negotiated as people interact. There isn’t one clear meaning that is inherent in our communication; it’s always subject to interpretation based on a variety of factors. Sociocultural theory relates more to the social context of a message and how cultural and historical factors might influence meaning (Mcleod). Lev Vygotsky was particularly interested in how children develop cognitively through speech, which mediates activity and organizes information in new and culturally significant ways. According to Vygotsky, behavior is an “interweaving” of both the biological reception of external stimuli and the psychological processing of information through a sociocultural lens. In other words, communication and how to interpret meaning are things we learn through relationships with other people, and often the way that we communicate changes when we interact with different groups of people—different discourse communities (University of Central Florida). Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger emphasize the idea that all learning is “situated” within complex systems where learning is “relational,” “negotiated,” “dilemma-driven,” and informed by “relations of power” (33, 36).

Social constructivist theory looks more at the individual within a social context—how an individual person might interpret information based on their unique perspectives, experiences, and ways of thinking and knowing. Using the social constructivist framework, “multiple realities” emerge as individuals organize and reconcile new information with their existing experiences and beliefs. Learning, therefore, is an active process as “the learner constructs his or her own knowledge” (Gipps 372). Social constructivism emphasizes the idea that, while communication is a collaboration that takes place in a social context, meanings are ultimately interpreted and internalized by an individual based on their connections and thought processes (Onore; Probst). There is still room for individual variations based on personal experiences, attitudes, and perceptions (Dweck; Powell and Driscoll). So even in the same social community with a shared communication system, one person might still interpret a message differently than someone else. In fact, chances are that two people won’t understand the meaning of a message in exactly the same way.

How does all of this relate to digital media? Quite simply, digital media is often what mediates our communication with people. To “mediate” means to go between two things or to “facilitate interaction” (Jones and Hafner 2). Jones and Hafner point out that while we tend to think of a “medium” as being something like a computer screen or a “mass medium” like a newspaper or radio, “all human action is in some way mediated” (2, original emphasis). By this definition, language itself is a medium that links people together to bring about a shared understanding, but as we’ve already discussed, coming to that place of mutual understanding can be difficult, and that’s especially true when messages are filtered through a screen, which increases the likelihood of misunderstanding (Sermaxhaj). Texts and emails offer very little by way of rich detail and contextual cues that would inform our interpretation of the message (Jones and Hafner). It’s hard to know sometimes if a message is meant to be funny, sarcastic, or angry. Subtle nuances are often absent or difficult to identify. What’s more, the language of digital media has evolved at a rapid pace—think about slang terms, SMS abbreviations, memes—which made it even harder for some people to fully grasp the meaning of a message (Kleinmen). Things like font choice, pictures, videos, and charts/graphs (things that aren’t available through spoken communication) can all be really helpful in adding clarity or depth to the meaning of a message, particularly when messages are crafted with readers’ perspectives in mind. Even so, it’s sometimes difficult to predict how a message might be misinterpreted or misconstrued, which is perhaps the biggest takeaway. It’s also impossible to pinpoint which interpretation is “correct.” Not every interpretation is equally valid. We’re all at times guilty of jumping to (false) conclusions at times or harboring biases that distort our perception of a message. However, nobody can stand outside of their individual perspective to access the “right” meaning. Communication is about negotiating meaning through open dialogue and mutual respect. It’s just as much about listening to other people’s perspectives as it is sharing your own (Edwards).

Activity 3.1

Make a list of your own terministic screens—the lenses through which you interpret information based on your own experiences, values, and beliefs. Each one of us has multiple screens, perhaps as an older brother, a college student, a Christian, a parent, an American, a child of divorce, and so on.

Come up with as many parts of your identity and background experiences as you can think of and consider how each one influences the way that you attend to and interpret information. Which ones are most central to your identity? How do they affect the way that you attend to and interpret various situations?

Underlying Agendas and Media Spins

Hopefully, it’s clear by now that online communication isn’t always easy. Language is often insufficient as a mediation tool that brings clarity and mutual understanding. Misunderstandings and disagreements are bound to happen, and so you might have to work a little harder to understand someone else’s ideas or help someone else understand your own. What makes everything even more difficult is the prevalence of misinformation and disinformation, perpetuated by economic and political agendas and media spins that add to the confusion and widen the chasm of political division. In many cases, false news stories and social media rumors have sparked civil discord and even violence as people get worked up over events that never happened or didn’t happen the way they were presented (CITS, “The Danger”). Even more disheartening is that many disinformation campaigns are intentional misdirections with the sole purpose of making money (Herasimenka). It’s tricky to navigate online spaces and distinguish fact from fiction, but since media stories and your interactions with other people surrounding these stories help shape your beliefs, worldviews, and relationships, having effective digital literacy means being more discerning about the stories you read and your reactions to the information you encounter.

Let’s start with a fundamental principle of how knowledge develops. Obviously, we accrue “knowledge” over time based on our interactions with the world and the “evidence” that we collect. Evidence might be our own experiences and the things that we witness firsthand, or as you might have guessed, evidence can also be secondhand based on what we learn from other sources—parents, teachers, friends, colleagues, books, news media, and so on. As we encounter new evidence that either confirms, contradicts, or extends our existing beliefs, we undergo a cognitive process of examining the evidence to either accept it as true or reject it as false. And that knowledge shapes our behaviors in specific ways. For instance, you (hopefully) brush your teeth every day (the action) based on the belief that it’s good for your teeth and breath, which is probably based on firsthand experience as well as information from your parents, your dentist, and so on (the evidence). You probably never sat down and really investigated your underlying beliefs about toothpaste; your beliefs developed subconsciously over time and solidified as you encountered more consistent evidence.

The formal term for how knowledge develops over time is called “epistemology” or the study of knowledge. This entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy examines the reason or rationale inherent in the cognitive process of adopting information as knowledge, also known as “cognitive success” (Steup and Neta). However, there are potential constraints that could lead to cognitive failure, in which we don’t adopt the information as knowledge, either because of the evidence itself or because of existing beliefs/values that contradict the new information. When existing evidence contradicts existing beliefs, we experience cognitive dissonance, a mental discomfort resulting from conflicting information (Kerwer and Rosman). Interestingly, the stronger our prior beliefs or the more grounded those beliefs are in our personal values, the less cognitive dissonance we experience because we are so quick to reject the new evidence. This is also known as the “backfire effect” as people “double down” on their beliefs even in the face of contradictory information (Wills).

Does that sound familiar? It might help to explain why people are so entrenched in their beliefs, why they are so quick to adopt information that confirms those beliefs, and why they are equally quick to reject anything that conflicts. They haven’t gone through the sometimes painful process of examining their current beliefs, where they come from, how valid they are, and how this new information might fit into or even change their beliefs and behaviors. However, the growing buzz about “fake news” and the idea that we are living in a “post-truth” era have created more skepticism among ordinary citizens (Schwarzenegger). However, most people are overly confident in their ability to detect fake news while believing that other people are fooled by media spins and fabrications (Jang and Kim). As Schwarzenegger put it in his study of media beliefs and personal use, “Users know that it is essential and socially favorable to be critical of information, but they rarely invest the energy and motivation to actually criticize it. Moreover, awareness of the need for information skepticism does not equate to being competent in critical practices.”

One thing to consider is the inherent connection between bias and a person’s vulnerability to fake news. Otherwise known as confirmation bias, this happens when information that we receive lines up with what we already believe—or want to believe. So we are quick to adopt that information as true. Ciampaglia and Menczer from Scientific American explain, “The fact that low-credibility content spreads so quickly and easily suggests that people and the algorithms behind social media platforms are vulnerable to manipulation.” In fact, often salacious, emotionally charged false information spreads more rapidly than information that is true (Vosoughi et al.). Ciampaglia and Menczer go on to identify three different types of bias that cause people to latch onto fake information: 1. Cognitive bias, resulting from “tricks” the brain uses to quickly sift through large amounts of information. The shortcuts bypass the more logical methods a person might use to decipher the credibility of a source. 2. Social bias, pertaining to the people we are around and the way information is filtered through friend groups. People tend to have a more positive impression of information if it comes from people in their social circle (another form of the echo chamber). “This helps explain why so many online conversations devolve into ‘us versus them’ confrontations” (Ciampaglia and Menczer). 3. Algorithm bias, utilizing what social media platforms and search engines consider to be the most compelling content for an individual user. However, the authors note, “But in doing so, it may end up reinforcing the cognitive and social biases of users, thus making them more vulnerable to manipulation” (Ciampaglia and Menczer).

There are obvious reasons to be skeptical of news sources. Even legitimate news organizations are made up of people with their own political values and beliefs, and there are external pressures from government agencies, advertisers, and interest groups that influence which stories are covered and the angles that are adopted. Going back to Burke’s concept of the terministic screen, all news stories are made up of selected details and descriptions. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the information provided is untrue, but it does mean that news stories aren’t 100% objective. They reflect a perspective that highlights certain details while ignoring others, and these selections always relate to underlying values and beliefs.

Then there is the prevalence of misinformation and disinformation, which create additional layers of confusion and chaos. The difference is about intent. Misinformation is inaccurate or misleading in some way, but it’s not intentional. Some people believe the false news stories they read online and promote them as fact because they are misinformed. They have been misled in some ways, but they aren’t trying to mislead others. Similarly, news outlets sometimes publish inaccurate information because they fail to verify the facts. This is particularly true following some sort of tragedy in which emotional tensions are high and news stations rush to post a story. Disinformation, on the other hand, is the intentional distortion of information or outright fabrications, often for the purpose of inciting panic, anger, or excitement. Tabloids, for instance, are known for sensationalized stories meant to grab readers’ attention and manipulate their emotions with little regard for accuracy or balance. Similarly, even reputable news organizations utilize sensational tactics to push ratings and political agendas (Vanacore). Even more scary are organizations that purposely promote fake news for the purpose of creating chaos and distractions (PBS News). This article from the Center of Information Technology and Society (CITS), gives several examples of fake news stories that have gone viral, demonstrating how easy it is (CITS, “Where Does”). In fact, Politifact.com, working with Facebook, put together a list of 330 fake or impostor news sites that either sound like legitimate news (ABCnews.com.co, for instance) or that target people whose political orientations make them less likely to question the information presented (AngryPatriotMovement.com, for example).

To make matters worse, there are two things to keep in mind. First, fact-checking sites exist to provide balanced information and help to either verify or debunk questionable information, but these organizations have their limits (CITS, “Protecting”). We’ve already established that “truth” isn’t fixed or stable, but beyond that, when looking into the details of a situation, fact-checkers often have no legitimate source other than the politician or organization in question. They can verify what the politician said, but they can’t verify the accuracy of that information. There are also inconsistencies between fact-checking sites when it comes to standards of truth or the verification process itself.

Second, even scientific studies, which are considered to be the standard of credibility and are used as the basis for many of our beliefs about the world, are prone to error, misinterpretation, and personal agendas. Though studies are designed intentionally to reduce bias and increase validity, no study is free from bias. They are all rooted in selections that the researchers make in terms of the study of the design, selection of participants, interpretation of the findings, and the language in reporting those findings. In fact, people often overlook the rhetorical nature of studies, in which researchers have a clear stake in promoting their own professional ethos and the importance of their findings. Furthermore, studies are all conducted and their results are interpreted by people who have their own ways of seeing and thinking about the world. Not only are news sites often guilty of distorting scientific studies to suit their own agendas (Woolston), but the studies themselves are sometimes flawed because they are purposely or inadvertently set up to reach a specific conclusion (Ioannidis). That’s why studies sometimes contradict one another and why they are often repeated. The more studies that come to the same conclusion, the more credible that conclusion becomes.

Activity 3.2

Find two or more different news stories reporting on the same event. These could be video reports, social media posts, or newspaper articles. The more types of sources you can collect, the better. Read/watch each one and make comparisons about their approach. Consider the details that are included as well as the language, both positive and negative, used to describe the event. How do these texts align? How do they differ? How might readers come away with different interpretations of the event based on which source they use?

If possible, see if you can find information about this event on a fact-checker site. Allsides.com, Emergent.info, FactCheck.org, or Snopes.com are all sites that try to verify information and provide balanced perspectives. What do these sites say about the event in question?

Alternatively, you might come up with your own list of details about the event that you think would need to be verified in some way. You could also come up with a list of questions that would help clarify the information you encountered in the articles and/or that would address information that seems to be missing.

The Dangers of the Echo Chamber

Given the uncertainty surrounding the information that we encounter online, it’s no wonder people are skeptical. In fact, many people are so turned off by the prevalence of fake news and political division that they avoid news media altogether (Edgerly et al.), which means that they’re not informed about current events or issues, and they aren’t participating in the conversations or the solutions. However, equally problematic are people who retreat to the safety of like-minded people and the (one-sided) information that supports their preexisting beliefs (also known as confirmation bias). As noted above, the more strongly people feel about particular beliefs, the less likely they are to examine the validity of those beliefs and to wrestle with conflicting evidence, no matter how valid it might be. Instead, they reflexively fall back on news sites and social media groups that validate their perspectives, and they become further entrenched in their own worldview instead of trying to understand the worldviews of others, find common ground, and negotiate solutions that are mutually beneficial.

In fact, one of the dangers of the echo chamber, besides the fact that it stifles personal growth, is that it prohibits original thinking (Pazzanese). Nobody is thinking critically or productively about the problems that exist, and even if they were, their ideas would immediately be dismissed because they don’t conform to the group mentality. Instead, it leads to confirmation bias and a deepening division that encourages people to think only of themselves. The previous chapter discussed some of the possibilities of civic engagement and progress that digital media affords. However, all too often, people are sucked into an online echo chamber that prohibits outward thinking, which can have devastating effects on public policy, random acts of violence by extremists, and the lived experiences of marginalized communities. In fact, Harvard law Professor Cass Sunstein points out the discrepancy between the ideal that the internet would be a place that celebrates diverse perspectives in the spirit of democracy and reality. He cites the “Daily Me,” a reference to how the echo chamber insulates us against other realities and normalizes our indulgence in personal interests, perspectives, feelings, and so on. (Pazzanese) It’s the opposite of social progress, and without digital literacies that encourage self-awareness and critical thinking, things will only get worse.

What Can You Do?

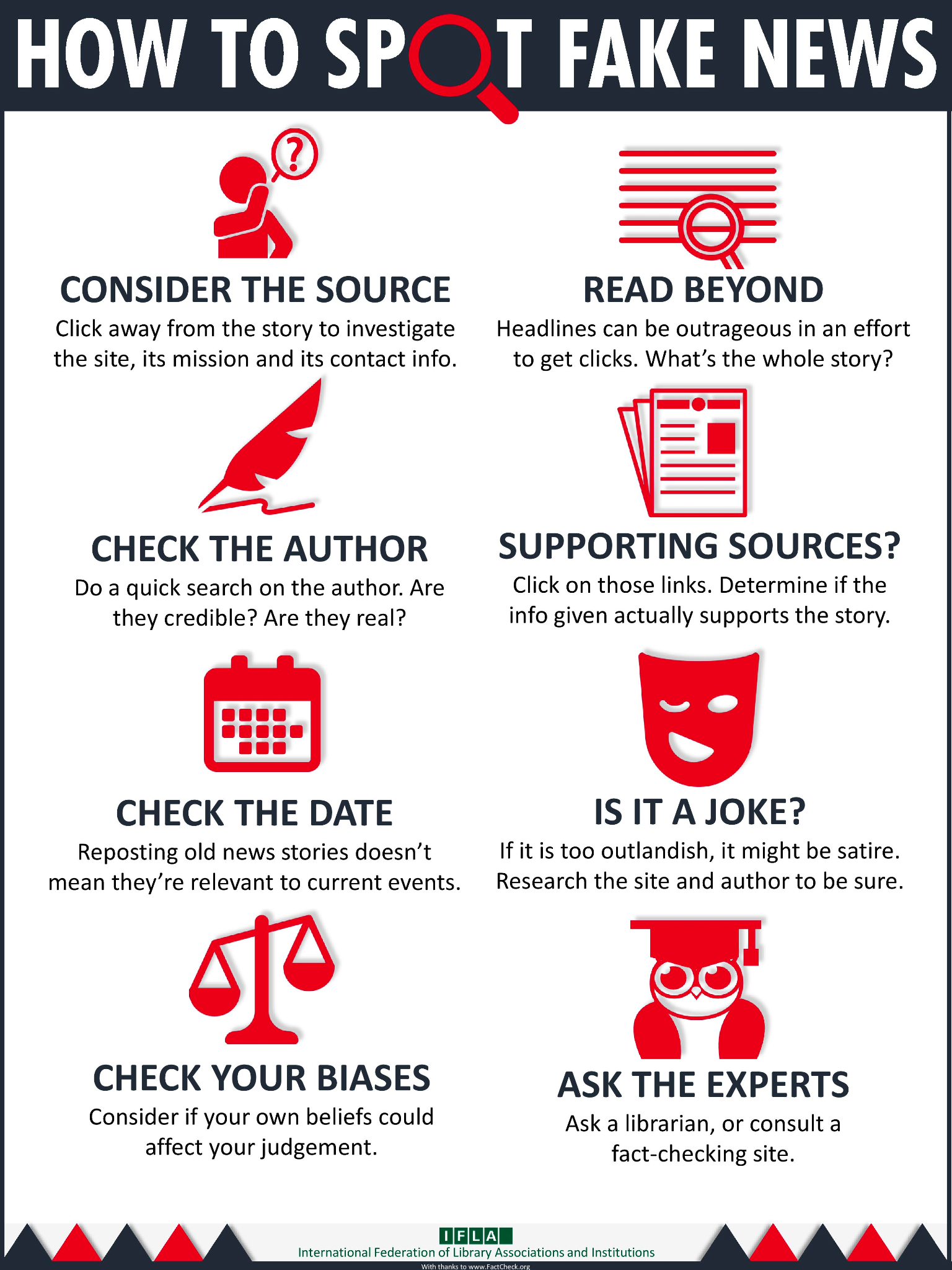

Originally, this section was going to be titled “How to Spot Fake News,” which is a significant aspect of digital literacy and an important countermeasure against the echo chamber mentality that actively suppresses information that isn’t personally beneficial. However, like much of the information presented in this chapter suggests, the problem lies a little deeper than a checklist that you might use to discern the “credibility” of a source (though there is one provided below as a starting point). We’re all predisposed in various ways to react positively or negatively to information that either reinforces or contradicts our existing beliefs. And besides, lots of credible sources contradict one another on important issues and seemingly fact-based events. To engage meaningfully with new information that you encounter—whether online or in person, on social media or in a scientific journal—first requires a little self-inventory.

For instance, when you encounter information that you immediately reject as false, take some time to consider why. What is it specifically about the information that you find untrustworthy? Can you pinpoint anything in particular about the writer, the news organization, the details that are presented, the writing style? List them out, but try to resist the urge to be dismissive or argumentative. Simply list them out for yourself so you can interrogate each item. Remember first off that information can be complex, full of major and minor details. A news article might have an inaccuracy or even a misspelling, but that doesn’t mean the entire article is false. Some items on your list might be valid reasons to be skeptical about the information (an underlying agenda, for instance, or a number of other articles that present conflicting information), and some aren’t (because the author is loyal to a different political party, for example, or because the author is different from you in some other fundamental way). The most dangerous item on your list might be “I don’t believe X because I already know Y.” So then, take some time to think more deeply—and honestly—about that. How do you know Y (whatever fact or belief that stands in contradiction to the new information presented)? Where did this information come from and why do you believe it so fervently? How valid are those experiences or other sources of information? And is the evidence mutually exclusive? In other words, is it possible that while your experiences are valid, it might also be possible that other viewpoints and experiences are also valid? It’s really not about being “right” or unraveling everything you think you know about the world. It’s about thinking critically and authentically.

Peter Elbow was an English professor and essayist whose ideas about teaching writing and subverting authority in the classroom had a pivotal effect on the composition field. In his writings in the 1970s and 1980s, he advocated for the “believing game,” which even then wasn’t popular, as most people like to play the “doubting game” (Elbow, “The Believing Game”). In contrast to our initial gut reactions to challenge something we hear, the believing game is a call to start out believing what you hear. You would look for the positives in others’ ideas and consider first what it means if they are true. Of course, it doesn’t mean that you have to agree with everything you hear or read, but it does open you up to engage more openly with other perspectives and to challenge yourself to see their value. As Elbow said in his 1986 book Embracing Contradictions: Explorations in Learning and Teaching, “The truth is often complex and…different people often catch different aspects of it.” When we embrace contradictions, we begin to understand that “certainty is rarely if ever possible and that we increase the likelihood of getting things wrong if we succumb to the hunger for it.”

The challenging part of self-inventory might be when you have to interrogate your reactions to information that you are inclined to believe, which you wouldn’t normally question at all because it seems so obviously true. Once again, you’d think about why. What is it about the author, the publishing organization, the information itself, the writing style, and so on that makes it seem credible? What are the underlying beliefs and assumptions that you have that might predispose you to believe or agree with this information? Can you pinpoint where those beliefs and assumptions might come from? What if you didn’t hold those underlying beliefs? What about the article might you question then? Again, it’s not about undoing all of your core beliefs; it’s simply an exercise in self-reflection where you think more critically about where your beliefs and attitudes come from. It might lead to some adjustments in your thinking, but the ultimate goal is self-understanding and reasoning based on logic instead of high emotion. It might also help you see that there is room for alternative viewpoints that are also logical and valid.

Of course, there are also strategies that you can use to discern the credibility of a source. A classic acronym that is easy to remember as you’re assessing a source of information is the CRAAP test:

- Currency: Is the information up to date? Of course, this criterion would be applied differently in different situations. Some topics like medicine or technology are constantly evolving, so it would be crucial to find a source that is current. For other topics—historical information, for instance—it might be okay, even preferred, to use sources that are a bit older.

- Relevance: Is the information relevant to your research question? This criterion is probably more useful for students in research courses, working to piece together a compelling research paper. Too often, students use sources that only loosely connect to their topic, resulting in a paper that is choppy and hard to follow. The point is to make sure that the source you use is focused on the same research question you are asking.

- Authority: Who is the person that is providing this information? What authority do they have on this topic? Something that is written by a credentialed expert in a particular field will have more authority on a related topic than a journalist or blogger without that specialized knowledge. Another thing that relates to authority is the research that the source presents. Where are they getting their information, and are they providing those sources as hyperlinks or citations? Does their own research look sound?

- Accuracy: Is the information accurate? Does it make sense and align with other information you’ve received on this topic? It might be a red flag if the information is contrary to everything else that you’ve learned on this topic. Again, you’d look more closely at their source of information or the methods they used to come to a conclusion (if it’s a study, for instance). Remember that a single study isn’t enough to prove that the conclusion is correct. Multiple studies that all arrive at the same conclusion have more weight.

- Purpose: What is the intention behind the source? What does it want you to think or do? How is it using information to be persuasive? At the very least, someone who has gone through the trouble of publishing information wants to catch your attention and wants you to agree that the topic is important. As we’ll discuss below, even academic studies have a rhetorical purpose beyond simply providing useful information that progresses our knowledge in a particular area. It’s always helpful for you to consider the financial or political motives of a source.

Though these guidelines don’t guarantee that the information is 100% accurate, they do help you gauge the credibility of a source. You should also be on the lookout for fake news stories with these other red flags:

- URLs that are created to look similar to a more established, credible news source

- Unique information/events that aren’t confirmed on other news sites

- Claims that are outlandish and provoke strong emotional reactions

Digital literacy and the quality of your digital writing hinge on your ability to navigate your way through the endless sea of online information, to distinguish credible information from fake news, to engage with other ideas, to understand the complexities of multiple realities, and to wrestle with your own attitudes and personal biases that might hold you back from genuine and productive discourse.

Activity 3.3

This section challenges you to consider the beliefs and attitudes that you have that provoke you to respond to information in certain ways. However, it can be difficult to honestly and accurately pinpoint attitudes and values. This short chapter in Principles of Social Psychology explains that our behaviors always stem from our underlying attitudes and beliefs (Jhangiani and Tarry). So to begin to understand your beliefs and attitudes, it might help to begin with your behaviors. Everything that you do is informed by some sort of underlying belief. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, you brush your teeth because you believe that you won’t have good dental hygiene if you don’t and because you value your health.

What other examples can you come up with? Think of some of your ordinary, everyday habits related to your diet, your exercise routine (or lack thereof), the tasks at work or school that you prioritize, your evening routine, and so on. Think about the things that you do and also the things that you don’t do. The way you spend your time and energy says a lot about the things that you believe and value. What do your daily activities say about you?

Discussion Questions

- What is a terministic screen? How does it influence the ways that different people interpret information?

- What does it mean that our terministic screens guide our selections of information as well as our deselections?

- What are sociocultural theory and social constructivist theory? When it comes to language and meaning, how are the two theories similar? How are they different? How do these two theories work together to extend your understanding of language and communication? How do they connect specifically to digital communication?

- How does information that conflicts with our preexisting beliefs create cognitive dissonance? What are people likely to do when they experience dissonance?

- What is the difference between misinformation and disinformation? How do they contribute to confusion and division?

- What is an echo chamber? Why do people succumb to the “Daily Me”? What are some of the dangers of this habit?

- What is the believing game? How can it be helpful when examining key issues?

- What are some ways that you can distinguish the credibility of a source?

- What are some key identifiers of fake news?

Sources

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action. Cambridge University Press, 1966.

CITS. “The Danger of Fake News.” CITS.uscb.edu, 2022, https://www.cits.ucsb.edu/fake-news/danger-social.

———. “Protecting Ourselves from Fake News: Fact-Checkers and Their Limitations.” CITS.uscb.edu, 2022, https://www.cits.ucsb.edu/fake-news/protecting-ourselves-fact.

———. “Where Does Fake News Come From?” CITS.uscb.edu, 2022, https://cits.ucsb.edu/fake-news/where.

Confessore, Nicholas. “Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far.” The New York Times, 4 Apr. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html.

Dweck, Carol. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Publishing Group, 2007.

Edgerly, Stephanie, et al. “New Media, New Relationship to Participation? A Closer Look at Youth News Repertoires and Political Participation.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699017706928.

Edwards, Renee. “Listening and Message Interpretation.” International Journal of Listening, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. Jan. 2011, pp. 47–65, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233145847_Listening_and_Message_Interpretation.

Elbow, Peter. “The Believing Game—Methodological Believing.” The Journal For Assembly of Expanded Perspectives on Learning, vol. 5, Jan. 2008, https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=eng_faculty_pubs.

———. “Methodological Doubting and Believing: Contraries in Inquiry,” in Embracing Contraries: Explorations in Learning and Teaching, N.Y., Oxford University Press, 1986.

“For 53% Reliable Information, Click Here.” Forbes, 31 Jan. 2003, https://www.forbes.com/2003/01/31/cx_da_0131topnews.html?sh=15b92ae831f3.

Gipps, Caroline. “Socio-Cultural Aspects of Assessment.” Review of Research in Education, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan 1999, pp. 355–392. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732×024001355.

Ioannidis, John A., “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.” PLOS Medicine, 30 Aug. 2005, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124.

Jang, Mo, and Joon K. Kim. “Third Person Effects of Fake News: Fake News Regulation and Media Literacy Interventions.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 80, Mar. 2018, pp. 295–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.034.

Jhangiani, Rajiv, and Hammond Tarry. Principles of Social Psychology. 1st Int. ed., 2022. https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/changing-attitudes-by-changing-behavior/.

Jones, Jeffrey M. “Americans: Much Misinformation, Bias, Inaccuracy in News.” Gallup.com, 20 June 2018, https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/235796/americans-misinformation-bias-inaccuracy-news.aspx.

Kapnick, Izzy. “Will Democrats Ever Regain Ground with South Florida’s Cuban Voters?” Miami New Times, 9 Nov. 2022, https://www.miaminewtimes.com/news/republicans-capitalize-on-fear-of-communism-in-florida-cuban-communities-15669381.

Kerwer, Martin, and Tom Rosman. “Epistemic Change and Diverging Information: How Do Prior Epistemic Beliefs Affect the Efficacy of Short-Term Interventions.” Learning and Individual Differences, vol. 80, May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101886.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Lumen Learning. “Discourse Communities.” Lumen, n.d., https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-englishcomp2/chapter/discourse-communities/.

Mcleod, Saul. “Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development.” SimplyPsychology.org, 18 Aug. 2022, https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html.

Onore, Cynthia. “The Student, the Teacher, and the Text: Negotiating Meanings through Response and Revision.” Writing and Response: Theory, Practice, and Research, edited by Chris M. Anson, National Council of Teachers, 1989, pp. 231–260.

O’Sullivan, Donie, and Geneva Sands. “Spread of Election Lies in Florida’s Spanish-Speaking Communities is ‘Fracturing Democratic Institutions,’ Advocates Warn.” CNN, 5 Nov. 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/11/05/politics/florida-election-lies-spanish-language/index.html.

Pazzanese, Christina. “Danger in the Internet Echo Chamber: To Combat Endless Feeds of One-Sided Data, Sustain Suggests an ‘Architecture of Serendipity.’” Harvard Law Today, 24 Mar. 2017, https://hls.harvard.edu/today/danger-internet-echo-chamber/.

PBS News. “The Long History of Russian Disinformation Targeting the US.” PBS.org, 21 Nov. 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/the-long-history-of-russian-disinformation-targeting-the-u-s.

Powell, Roger, and Dana Driscoll. “How Mindsets Shape Response and Learning Transfer: A Case of Two Graduate Writers.” Journal of Response to Writing, vol. 6, no. 2, 2020, pp. 42–68. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=journalrw.

Probst, Robert E. “Transactional Theory and Response.” Writing and Response: Theory, Practice, and Research, edited by Chris M. Anson, National Council of Teachers, 1989, pp. 68–79.

Schwarzenegger, Christian. “Personal Epistemologies of the Media: Selective Criticality, Pragmatic Trust, and Competence—Confidence in Navigating Media Repertoires in the Digital Age.” New Media & Society, 20 Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856919.

Sermaxhaj, Grese. “Online Communication and Misunderstanding.” Youth-Time.eu, 18 Mar. 2020, https://youth-time.eu/online-communication-and-misunderstanding/.

Steup, Matthias and Ram Neta. “Epistemology.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology/#WhatKindThinEnjoCognSucc.

Stob, Paul. “‘Terministic Screens, Social Constructionism, and the Language of Experience: Kenneth Burke’s Utilization of William James.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 41, no. 2, 2008, pp. 130–152, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25655306#metadata_info_tab_contents.

University of Michigan Library. “‘Fake News,’ Lies and Propaganda: How to Sort Fact from Fiction.” UMich.edu, 4 Aug. 2022, https://guides.lib.umich.edu/fakenews.

Vanacore, Rylan, “Sensationalism in Media.” Reporter, 12 Nov. 2021, https://reporter.rit.edu/news/sensationalism-media.

Vygotsky, Lev. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, edited by Michael Cole, Vera John-Steiner, Sylvia Scribner, and Ellen Souberman, Harvard University Press, 1978.

Woolston, Chris. “Scientist Criticizes Media Portrayal of Research.” Nature, vol. 523, no. 505, 24 July 2015, https://www.nature.com/articles/523505f.