17 Remix Culture and Copyright

At the time of this writing, ChatGPT is quickly emerging as a sophisticated AI that can compose complex, seemingly “original” texts and can craft a text to follow the specifics of many types of prompts (Open AI). It can write computer code, short stories, academic essays, songs, cover letters, emails, and much more. Ironically, not only can this new AI be used by students to write academic papers, it can also be used by teachers to grade essays and give detailed feedback, which would lead to a rather sad state of affairs in which nobody, not even writing teachers, is doing the intellectual and creative work of composing original texts. It’s easy to see why so many people are concerned about the consequences of such technologies, which allow “writers” to sidestep the cognitive, often emotional and intensely personal, process of putting thoughts and experiences into words—the right words. For many of us, it’s a labor of love, and the satisfaction of producing a thought-provoking text that can engage the emotions and imagination of an audience is tied up in the inherent struggle of the writing process. It’s much more than a reflection of ideas that are already fully formed and simply need to be translated into text. The writing process is generative, where ideas and connections take shape that wouldn’t have otherwise (Sayre). In other words, writing facilitates personal growth, critical thinking, and human connections that AI can’t replicate—and even if it could, where would that leave us? Much of the reason that copyright exists is to validate human expression and the unique ways that writers and artists go about putting their ideas into words and images.

On the other hand, the word “original” when it comes to creative and academic writing is fairly misleading. Many discussions of the writing process begin with a stage called “invention,” where writers “discover the ideas upon which their essays will focus” (Vanderbilt University). However, many people argue that true invention is a myth, that people don’t create new ideas and connections as much as they discover possibilities that existed all along but hadn’t been recognized in quite that same way. Architect David Galbraith says, “We can only select things that are possible, [sic] invention is merely when the possible is new. Real invention, out of nowhere, not selecting from the possible, is impossible, by definition.” Then there’s the reality that in many instances, there aren’t really new ideas as much as there are new ways of applying old ideas—or different ways of combining seemingly disparate ideas to create something new. That’s what a remix is. It restructures existing content, making selections and deselections from a variety of texts, to create something new and interesting. It’s a lot like cooking. Chefs don’t create brand new ingredients; they combine existing ingredients in different ways, sometimes making adjustments to existing cooking processes, in order to create something fresh and interesting. The whole idea behind “fusion” is that classic recipes from different cultures are combined to create new flavors and culinary experiences. The same is true for writers who combine and build upon existing words and ideas. If you really think about it, all of the seemingly “new” ideas that people have emerge from somewhere—something someone else says, a process or experience that triggers an “aha” moment, an existing line of thought that can be retooled, the cultural nuances that influence your way of seeing and thinking about the world. It’s impossible to trace those disparate strands that come together at the exact moment a “new” thought enters your mind, but it didn’t materialize from nothing. All writing (and thinking) is a remix. According to Everything Is a Remix, “When we create, we often seem alone, but we are in fact together” (Ferguson), referring to the ways that ideas transcend time and space, always setting the stage for and guiding the choices of what comes next.

As you can probably see, there are two opposing ideas at work in this chapter, complicating the very notion of what is an “original” work. Writers don’t write in a vacuum. They are influenced by other artists, historical events, cultural contexts, and existing texts, and human progress depends on our ability to build on what came before. What’s more, with the digital tools that are now so widely available, it’s easier than ever before to create remixes—mashups, edits, blends, and megamixes. While many amateur works of this nature exist that aren’t particularly inspiring, there are also many digital remixes that are engaging, enjoyable, and thought-provoking, providing an outlet for the author’s creativity and expression and adding to the collective repertoire of ideas from which we all benefit. However, copyright law is still a fundamental concept for all published works, serving to protect the artistic integrity and financial remuneration of the author. The purpose of copyright was to promote the development of new ideas by providing a mechanism of control and financial incentive for people who invest their time and expertise in scientific and creative works. According to the Copyright Alliance, “The theory is that by granting certain exclusive rights to creators that allow these creators to protect their creative works against theft, creators receive the benefit of economic rewards and the public receives the benefit of the creative works that might not otherwise be created or disseminated.” In many cases, copyright law creates a barrier for people to redistribute, remediate, remix, or revise someone else’s work without their express permission, and now that there are so many digital tools that make those very practices so much easier, it’s more important than ever to understand what the rules are.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the history of remix culture and explore arguments made by Lawrence Lessig and others who see the inherent value in being able to remix. We’ll also explore different examples of remix and the ways these examples have expanded in recent years with the development of new social media platforms. The second part of the chapter will look more closely at copyright law within the context of the digital age, providing key terms and guidelines about the rules as well as the consequences of breaking those rules.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the arguments advanced by remix culture about the importance of creative freedom and the inherent remix that shapes all thoughts and texts.

- Learn about key terms and the different types of remix that are possible in music and how those same terms can be applied to other types of texts.

- Consider how remix has shaped the development of cultures throughout history and how remix culture has emerged in response to stricter copyright laws.

- Connect the shift between “read-only” culture to “read-write” culture with the advancements of digital technology.

- Understand both sides of the debate regarding the benefits and drawbacks of remix culture.

- Learn about copyright law and the types of works that do and do not qualify for copyright.

- Learn about the law of fair use and be able to apply it to a wide range of works.

- Learn about the different types of copyright licenses and the permissions they afford.

Remix Culture

Remix has become an umbrella term to refer to derivative works, created by combining or editing existing content. As we’ll see in this chapter, remix culture encourages derivative works, believing that digital editing tools have provided a valuable way for more people to take an active role in the production of creative and scientific works (Murray). Many proponents of remix argue that the process of remix is an inherent part of the creative process and that copyright laws have become too strict, thus inhibiting the creative process and prioritizing corporate greed. Others see the more blatant forms of remix—beginning with others’ music, videos, images, or texts—as mimicry, which sidesteps the creative process, unfairly leverages the talents of other artists, and impedes the unique voices, perspectives, and styles that might have emerged otherwise.

However, before we examine the history of remix and the various perspectives, let’s look at a few key terms and the overwhelming prominence of remix. On a fundamental level, to “remix” means to mix again—to take existing elements and rearrange them to create something different. “Remix” is an umbrella term that captures all kinds of processes (adding, removing, or adjusting elements in some way) in a variety of media (text, music, film, and graphic art as well as live plays and spoken word). According to Remix Theory, it’s “the activity of taking samples from pre-existing materials to combine them into new forms according to personal taste” (Navas). Under this broad definition, several different types of remix exist, often related to audio production since that’s one of the most common forms of remix:

- Production remix—starts with the “stem” of an old song, utilizing new instruments and other stylistic choices to create something different than the original. In some cases, the music may change dramatically to accommodate the original lyrics, or the lyrics themselves might change to reflect new interpretations of the song. An “official remix” happens with the original artist’s consent, and a “bootleg” does not.

- Flip or sample flip—uses a small sampling of an original song and turns it into a completely new piece of music.

- VIP or variation in production—is a remix done by the original artist to put a new spin on an old song.

- Edit—makes minor changes to the song related to tempo or elements that might be added, dropped, or changed. These types of edits are often done by DJs to make songs flow together better or to make a song more entertaining for a live audience on a dance floor.

- Mashup—mixes together two or more different songs to create a new track. In some cases, the words of one song are combined with the instrumentals of another.

These musical remixes were around long before the rise of digital media and the technologies that make it so much easier to sample, remix, and mashup songs. For instance, Madonna was known for remixing her own songs in the 1980s, which is one of the ways she gained popularity (O’Brien). Art of Noise (The Art of Noise Online) and Girl Talk (Booker) created new songs entirely out of existing works. In fact, some bands such as Nine Inch Nails and Erasure have encouraged fans to remix their music.

In addition to the possibilities that exist in the music industry, the term “remix” has been extended to include many different types of compositions—literature, paintings, film, and graphic design. Many types of remix have become much easier and more commonplace with the rise of technologies like Photoshop and GarageBand, but many other examples have existed for centuries. Some common examples of remix include:

- Food recipes, which are modified and combined with other recipes to create something new.

- Parodies are works that comment on or make fun of another work, often in a humorous or satirical way. While many contemporary parodies exist (e.g., Weird Al Yankovic [Sulem] or Family Guy [Lagioia]), this genre dates back to ancient Greek literature (SuperSummary).

- Paintings and graphic arts combine new and existing elements. Think of how many times the Mona Lisa or American Gothic have been remixed. Many examples of remixes exist that have taken historical photos and paintings and reimagined them with a more contemporary twist (Rogers).

- Fanfiction creates new stories from characters and settings that already exist (Collins). While this type of writing has existed for a long time, the internet has made it much easier to access existing stories and for writers and readers to come together to share and discuss their work.

- Wiki platforms like Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons encourage users to access, add to, and remix existing content in order to invite collaboration and add to the existing pool of knowledge.

- Book mashups combine two or more existing stories into one. Some examples include Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, and It’s a Wonderful Death (Goodreads).

- Literary intertextuality is where one text alludes to another text, either directly or implicitly. In some instances, this includes quoted material from an original text. For instance, in Dead Poets Society, Robin Williams quotes from Walt Whitman’s poem “My Captain.” Or it might take the form of an allusion, which makes an implicit connection to another text. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 alludes to the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland, which would have created an instant image in readers’ minds. Intertextuality can also include the retelling of classic stories. For instance, the more contemporary film 10 Things I Hate about You is a contemporary take on Shakespeare’s classic play The Taming of the Shrew.

- Memes and GIFs are also forms of intertextuality, relying on the audience’s familiarity with a particular photo or scene from a movie in order to understand the implied meaning.

- Open source software makes it possible for users to access code that would otherwise have been proprietary so that they can add to, modify, or enhance the code in some way to create something new (OpenSource.com).

- Film can be used to blend a variety of content. Many contemporary movies are adaptations of classic novels, comic book stories, or older films. YouTube videos and TikToks also incorporate elements from other videos, movies, photos, and songs.

- Academic texts build from other academic texts, often implicitly through quoted information and citations but also implicitly through various genre conventions, organizational strategies, and rhetorical choices. Most scientific studies build on studies that have already been conducted.

Activity 17.1

The above section provides some basic types of remix along with several examples. For this activity you should:

- Review the different types of remix listed and see if you can come up with more examples that would fit under each category.

- See if you can identify types of remix that haven’t been identified above along with an example or two.

History of Remix Culture

The history of remix culture is a long one, and it’s incredibly complex. Some texts are fairly obvious in the ways that they have purposely integrated elements from preexisting texts. Other texts are much more subtle, and it would be impossible to trace all of the different experiences that came together to influence all of the artistic (or academic) choices the author(s) made. While this section endeavors to provide a very brief overview of that history, the main point is to trace the underlying arguments by many proponents of remix culture and to demonstrate how prevalent the concept of remix has been throughout history. As we will see, many high-profile texts and pivotal inventions are a form of remix, which begs the question of where our society might be now if it weren’t for remix culture.

Though many people might equate the digital age with the rise of remix culture, the reality is that remix has been around for centuries, often as a comment on the culture of the time and almost always building from other works that came before. Writing for the World Intellectual Property Organization, Guilda Rostama says, “Most cultures around the world have evolved through the mixing and merging of different cultural expressions.” She goes on to list examples of oral traditions dating back to medieval times, Renaissance architecture inspired by ancient Rome and Greece, and folk traditions in the nineteenth century. Some also note that the Panchatantra, dating back to around 400 BCE is an early form of remix (Roy). Another example can be found in the early Quaker movement in the seventeenth century, in which followers told Bible stories in their own words and reenacted scenes from the Bible (Daniels).

However, remix culture truly emerged in the twentieth century as new technologies made different types of remix possible. In Everything Is a Remix, Kirby Ferguson traces the remix history of individual songs and artists and the way genres of music took shape through remixing techniques. For instance, he notes that as early as the 1970s, DJs were looping songs together at dance parties, alternating between two or more songs, and speaking words to the beat of the music, all of which sparked the beginning of rap. Sampling became more complex, combining different kinds of sound effects and mixing techniques and expanding to other genres like hip-hop and rock. All songs, according to Furguson, employ remix ideas, starting with existing ideas and transforming and combining them into something else. Some examples are fairly subtle, perhaps using chords, stylistic techniques, and turns of phrase that are fairly common. Others are more obvious and have sparked a great deal of controversy over the years. For instance, Greg Gillis’s Girl Talk project was a “series of flagrantly illegal mashup albums that can be downloaded for free. Each song is composed entirely of dozens of uncleared samples by popular artists” (Furgeson). Gillis is featured in the 2008 open source documentary RIP: A Remix Manifesto, which explores the concept of copyright in the digital age (Gaylor). Led Zeppelin is another group that has been criticized for copying lyrics from other songs, even being accused of plagiarizing part of the song “Taurus” in its 1971 release of “Stairway to Heaven.” The lawsuit finally came to court in 2016, with the jury deciding that “the descending musical pattern shared by both songs had been a common musical device for centuries. One example cited was Chim Chim Cher-ee, from the 1964 Disney musical Mary Poppins” (BBC).

As new remix techniques emerged in the 1970s, the Copyright Act of 1976 was put in place to thwart unrestricted use of licensed materials, imposing strict financial penalties to anyone who violated the rules. For instance, if the Led Zeppelin lawsuit cited above had turned in favor of the plaintiff, Zeppelin would have had to repay somewhere between $3 million and $4 million. As a result of these restrictions and penalties that some people felt discouraged creativity and civic participation, remix culture advanced as a form of protest. Professor Lawrence Lessig is a Harvard law professor and a political activist who founded Creative Commons in 2001 to provide a platform where people can access, share, and build upon other people’s work. In his book, Remix, Lessig says copyright restrictions of the twentieth century discouraged people from taking an active role in the creative process. “The 20th century was the first time in the history of human culture when popular culture had become professionalized, and when the people were taught to defer to the professional” (29).

The advancement of digital media was also an important shift toward remix culture. While analog media encouraged a “read-only” culture in which people were passive consumers, digital media allowed a “read-write” culture that was more reciprocal, allowing people to not only consume but produce creative works. Videos and audio files could be reproduced over and over without losing quality. In the 1980s, home computers became more popular and the free and open software movement sparked a cultural shift in favor of resources that allow materials to be freely used and edited by anyone (Tozzi). Also the rise of Web 2.0, defined by platforms that allow for more collaboration and user-generated content, provided even more opportunities for people to remix texts, photos, videos, songs, and more. Now anyone can create remixes, edits, and spinoffs, and it is a very common form of expression that provides entertainment and provokes further conversation.

The Remix Controversy

Despite its prevalence, remix culture is controversial, begging the question of where the line is between creative inspiration drawing that builds on previous ideas and outright plagiarism. On the one hand, people argue that remix is a natural part of the thought process and that it has immense cultural and social value. Kirby Ferguson, for instance, argues on his website Everything is a Remix as well as his TED Talk Embrace the Remix that all ideas are essentially a remix, incorporating the basic elements of copying, combining, and transforming previous content. We learn first by copying what others have created, which becomes a gateway to transforming and combining elements to create something “new.” “I think these aren’t just the components of remixing,” Furgeson said in his TED Talk. “I think these are the basic elements of all creativity. I think everything is a remix, and I think this is a better way to conceive of creativity.” Similarly, Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel point out that remix extends far beyond the act of combining or revising songs or pictures. It’s a broad concept that defines what a culture is: “We could say that knowledge is a remix, that politics is a remix, and so on. Always and everywhere, this is how cultures have been made—by remixing: taking what others have created, remixing it, and sharing with other people again” (Lankshear and Knobel).

As ChatGPT, Bard, and other generative AI platforms have emerged, educators and digital writers alike have found more complex and productive uses for these technologies, beyond the simple (and largely unethical and ineffective) practice of inputting a prompt and then copying and pasting the resulting text. For instance, these platforms can be used to help brainstorm topic ideas, create outlines, provide examples of genre conventions, as well as expand or revise content that has already been written. In fact, a recent study by Wieland et al. in Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence found that people are more productive when brainstorming or developing ideas using artificial intelligence (a platform that wasn’t judging their ideas) than with another person. In other words, like all other writing where every idea and writing strategy is a remix, writing produced in collaboration with generative AI is also a remix, and that isn’t always a bad thing.

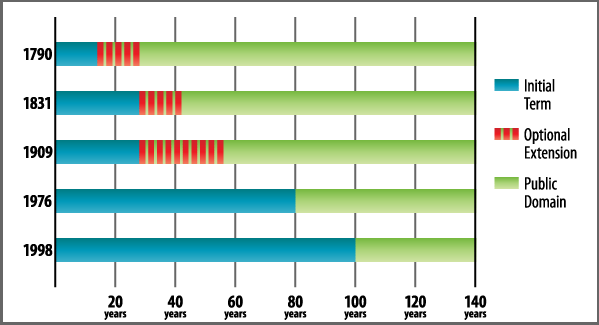

Of course, proponents of remix culture are quick to point out the many examples of remix, many of which are identified above, that have greatly benefited society as a whole. Ferguson’s TED Talk provides several more examples of remixes by Bob Dylan and Steve Jobs. He has quotes from Picasso as well as Henry Ford clarifying that they didn’t create anything entirely new; they built on artwork and discoveries that came before. Many classic examples of remix can be found in the works of Walt Disney. Not only is Disney remaking many of the old classics, like Lion King and Dumbo (Simmonds), but many of the original characters in Disney movies originated from other stories in the public domain (Khanna). Even our contemporary version of Mickey Mouse underwent several remixes over the years on his journey to being the Disney icon (Trammell). However, in addition to the prevalence of remix, advocates also argue for the social value. Ferguson says, “Rixing can empower you [to] be more creative. Remixing allows us to make music without playing instruments, to create software without coding, to create bigger and more complex ideas out of smaller and simpler ideas” (“Everything”). Not only does remixing add to the cultural repertoire of artistic works, but it teaches people to actively engage in political discussions and cultural activities, providing a means of participation, critique, and even social protest. For instance, memes (Williams) and hashtags (Vickery) have been used to advance political movements like the #MeToo and the #BlackLivesMatter movements. It’s obvious, then, why advocates like Ferguson and Lessig (“Re-examining”) argue that copyright law is too restrictive, stifling creative and political expression, used for the financial gain of artists and other creators who used remix in their own creations. Their argument is predicated on the way that copyright law has changed throughout history. While the original copyright law in 1790 allowed for 14 years of copyright protection for a work with the opportunity to renew copyright for another 14 years—28 years total, the current interaction extends copyright protection for the life of the author plus another 70 years. Their argument also assumes that “remix” involves some sort of transformation of the original work. Copying or plagiarizing a text isn’t the type of “remix” that Ferguson and Lessig support.

On the other side of the debate, people argue that remix culture encourages plagiarism, that artists should have the rights to their own creative works and be able to control how they are altered and disseminated. In some instances, remix takes the original text out of context and alters it to purposely misrepresent the original idea. There is also the fact that many people are paid for their creative works, and they lose money and notoriety when their works are taken without financial compensation or due credit. An article in The Atlantic by Adrienne LaFrance underscores this problem by describing the experience of an artist named Gelila Mesfin, whose artwork was displayed on Pinterest without proper credit and then copied by someone else who used it as a mural as part of an urban planning initiative, calling it his own form of art. LaFrance says, “The same tools that enable artists to share their work widely makes it easier for those same artists to get ripped off by outsiders who sometimes profit from this kind of theft. These incidents are especially fraught, too, because of how often the person benefiting is already privileged and powerful.” In other words, the professionals who spent years developing their craft and developing the skills to create various forms of art lose out because of blatant theft by people who don’t have those same professional talents and skills. Craig Robinson is another artist who was mentioned in LaFrance’s article because his work was copied by someone else using his ideas who claimed that “everything is a remix” when he confronted her. “Which is convenient, isn’t it?” Robinson said. “Very convenient that your school of thinking allows you to piggyback off my idea, my work, my hours and hours and thousands of hours to get yourself a sugary write-up in the New York bloody Times and exhibitions in New York” (qtd. in LaFrance).

Another argument against remix centers on the fact that many of the original artists are from marginalized groups whose cultural expressions are appropriated and twisted to fit someone else’s agenda. April Reign, the managing editor of the website Broadway Black, told Wired magazine, “I cannot name a person of color who has created something viral and capitalized off of it” (qtd. in Ellis). Similarly, Thomas Joo argues that remix isn’t really a form of equal opportunity in which individuals find their voice. More often than not, he says, the “dominant [cultural] institutions appropriate from the underdog” and “use their influence to ‘drown out’ those individual voices” (415), which only reinforces dominant ideologies and the social injustices that those individual voices are trying to work against.

It’s a complex issue as both sides advocate for artistic freedom and the value that such expression has in society. The digital age has made things more complicated as olds works are remediated into new forms and have made it possible to significantly transform the original work, sometimes beyond recognition. Judges tend to focus on the degree of transformation of a remixed work as well as the type of alterations made to the original (LaFrance). There is also the question of the author’s original intent and whether they are still living, assuming that the original author can be identified. In fact, as remix culture advances and digital technologies continue to evolve, the very concept of authorship has become a complicated one, making it difficult to identify where even our most “original” ideas came from and what we can claim as our own.

Activity 17.2

Write a reflection based on the controversy surrounding remix culture. Which side of the controversy do you agree with more and why? What are some of the most compelling arguments on the other side of the debate? You should also comment on your own opinion regarding the line in which “remix” becomes “plagiarism.”

See if you can find other examples, like the ones cited above, to support your position.

Copyright Law

The debate about remix culture is directly related to the idea of intellectual property and the desire to protect authors’ rights and encourage ingenuity. Copyright law is intended to provide that protection. Grounded in the U.S. Constitution, copyright literally means “the right to copy,” and as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, it’s automatically given to the author of a work, whether it is written text, graphic art, or a recording. It provides that individual with the sole right to publish, print, copy, and distribute their work (U. S. Copyright Office, “Copyright Law”). While many people register their work with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to have documented proof in the event that someone violates their copyright, an original work is protected automatically “the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form that is perceptible either directly or with the aid of a machine or device” (U.S. Copyright Office, “Copyright in General”). In other words, a text that exists in your mind isn’t protected, but the minute that you write it down on paper or type it up on a screen, it has copyright protection. Similarly, a dance or theater performance isn’t protected when it is performed because it’s not yet in a “fixed and tangible” medium. However, if the play is written down or the dance is recorded on film, then it has copyright protection.

You might typically associate copyright with literary texts—poems, short stories, novels, memoirs, and so on—but it extends to many different types of authorship, including academic essays, news stories, songs, computer software, architectural blueprints, sculptures, movies, and more. To receive copyright, three elements must be present:

- Originality. It is the work of the author and hasn’t been copied from someplace else. Based on our discussion in the remix section of this chapter, it’s clear that the term “original” is hard to pin down. According to the University Libraries at the University of North Texas, “This doesn’t mean it has to be ‘novel’ in the way an invention must be to get a patent.” While the idea itself might not be new, the expression of that idea should be unique to that author.

- Creativity. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, a work must have a “modicum” of creativity to have copyright. This is in some ways up to the interpretation of individual courts, but the main idea is that lists of names and numbers don’t require any sort of creativity while other forms of expression that are less straightforward and obvious do.

- Fixation. As mentioned above, the work must be in a fixed medium that is stable and can be perceived by an audience.

Given these criteria, you can probably see that many things aren’t protected by copyright. For one thing, there’s a difference between a copyright, a patent, and a trademark. The U.S. Copyright Office explains that a copyright applies to “works of authorship,” while a patent is more appropriate for an invention, process, discovery, or scientific creation. A trademark is more about branding, intended to protect things like logos, symbols, taglines, and slogans that are associated with a particular brand. In other words, a tagline wouldn’t be protected by copyright, but it might be eligible for trademark protection. Other things that aren’t eligible for copyright include the following (U.S. Copyright Office, “Circular 33”):

- Ideas, concepts, or processes. As stated above, these might be more appropriate for a patent. While you certainly could write down the idea or create a drawing that represents a particular system, the word choice or the drawing would be protected by copyright, but the underlying idea or process isn’t.

- Names, titles, and short phrases. This one might be surprising: the title of a work, such as a novel or a movie, isn’t protected by copyright. Similarly, the name of a business, a slogan or catchphrase, the name of a character, or a domain name or URL can’t be copyrighted.

- Facts and discoveries. These are things that weren’t created by an individual and therefore aren’t eligible for copyright or patent protection.

- Straightforward language about a process or function. While very creative expressions of an idea or process can be copyrighted, some expressions are very common or don’t have creative elements. For instance, the phrase “Preheat the oven to 350 degrees” is a very common phrase that doesn’t have any creativity. It wouldn’t be protected by copyright.

- Typeface and special lettering. In other words, a specific font can’t be copyrighted.

- The layout or format of a document or design. The actual design would be protected by copyright, but a template of a web page or a magazine layout wouldn’t.

- Blank forms, such as order forms, scorecards, address books, timecards, and calendars. “Blank forms that are designed for recording information and do not themselves convey information are not copyrightable” (U.S. Copyright Office, “Circular 33”).

Fair Use

The main exception to copyright law is called fair use, which allows individuals to copy portions of a copyrighted work for certain purposes without explicit permission to do so. In many instances, fair use is about copying only a small part of a protected work in order to fulfill a noncommercial purpose, such as archiving, teaching, critiquing, news reporting, or researching. A teacher in a classroom, for instance, can photocopy a page out of a textbook and hand out multiple copies to students for the sake of teaching a specific concept or idea.

According to Copyright Law Section 107, several elements should be considered when deciding whether a protected work can be copied under fair use (U.S. Copyright Office, “Chapter 1”):

- “The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.” If something is copied for commercial reasons in order to make money or promote a product or service, then it wouldn’t be protected under fair use. If something is reproduced for educational purposes or noncommercial purposes, it is more likely to be considered fair use, though there are other factors to consider.

- “The nature of the copyrighted work.” Copyright is intended to protect creative expression, and therefore more creative works like novels, poems, or songs are less likely to be considered fair use than if it were a more technical or factual work like a textbook or a news article.

- “The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.” In this case, courts will consider the amount of the original work that is copied as well as the quality of the work. Smaller portions of the work are more likely to be considered fair use than larger portions. However, if the selected portion is a really significant section of the piece, containing the main idea or underlying personality of the whole thing, it might not be protected by fair use, even if it is a small portion.

- “The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” If the use of the copyrighted work creates financial harm to the creator, then it’s less likely to be considered fair use. This is especially true if the use of the material is preventing people from buying their own copy of the original.

Harvard University notes that recently, courts have paid more attention to the degree to which the original work is “transformative,” meaning that it has been added to or built upon in a way that changes the nature of the original work and provides new meaning (a.k.a. remix). While works copies of a work don’t have to be transformative to be fair use (e.g., copies of a textbook excerpt in a classroom), “a use that supplants or substitutes for the original work is less likely to be deemed fair use than one that makes a new contribution and thus furthers the goal of copyright to promote science and the arts” (Harvard University). The Harvard University article goes on to mention other factors like common practice and the motives of the person copying the material to help determine whether it is fair use.

Activity 17.3

Review this worksheet that was created by the Copyright Advisory Office at Columbia University Libraries. It has a checklist that goes through each element of fair use. Use it to consider the various examples of copying listed below and whether each one is fair use and why or why not. Keep in mind that some of the examples are fairly complex and are open to interpretation by a jury.

- You repost or share a link to someone else’s social media post on your own account.

- A teacher copies a photo from Google Images and pastes it into their slideshow for class.

- A teacher photocopies an entire chapter of a textbook and distributes it to students so they don’t have to purchase the book.

- A friend sends you a picture they took with their digital camera, and you use it to create a meme that you post on your social media page.

- Part of a popular song is used in a commercial.

- You edit part of a published film by inserting yourself into the scene and then posting it on YouTube.

- You and your friends perform a famous part of a song in your garage.

- You take the color scheme and overall layout of another website and apply it to your own.

Understanding Copyright Licenses

Because texts are so readily available in online spaces, it’s important to be familiar with the different types of copyright licenses and what they mean. In all instances, the creator holds the copyright and gets to decide which type of license they want to use. A standard copyright, as noted above, prohibits other people from copying, adapting, or redistributing their work. However, there are other types of licenses (known as copyleft) that provide more flexibility in how they can be used. The most common copyleft license that allows the author to retain basic rights over their work while still allowing others to reuse it in different ways is a Creative Commons license. Founded in 2001 by Lawrence Lessig (an advocate for remix culture and more lenient copyright laws), Creative Commons “is a nonprofit organization that helps overcome legal obstacles to the sharing of knowledge and creativity to address the world’s most pressing challenges.” As they explain on their website, the Creative Commons licenses are composed of four different elements or rules:

- BY: attribution is required (the author must be given credit)

- NC: No commercial use (can’t be used to make money)

- ND: No derivative works (can’t be changed)

- SA: Share alike, which applies only to derivative works and requires that they have the same license as the original.

Obviously, an ND and SA can’t be combined to form a CC license, but the other elements can be combined in various ways to form six different licenses:

- CC BY (least restrictive)

- CC BY-SA

- CC BY-ND

- CC BY-NC

- CC BY-NC-SA

- CC BY-NC-ND (most restrictive)

Each Creative Commons license gives permission for people to share, but they include different rules that must be followed. Another type of license not listed above is the CC 0, which is the designation used for a work that is in the public domain. It is the same thing as “no rights reserved,” meaning that the author has relinquished any claim on the work and it can be used, adapted, and copied without limit.

Understanding how copyright works and the types of licenses that are available is important so that you can ensure you are using material legally. All work should have some sort of copyright designation, but when in doubt, you should always contact the original author and get written permission to use their work in whatever way you intend.

Remix culture and copyright law have evolved in tandem over the last few decades as digital technologies have enhanced our ability to access, modify, and redistribute information. Interestingly, they are both focused on protecting the artistic and scientific progress of our society, but they envision the creative process in different ways. Whatever school of thought you espouse, it’s important to understand the ways that digital media encourages a more participatory culture where new ideas and different forms of expression emerge, but it’s equally important to understand the legal restrictions that are in place and the consequences of misuse.

Discussion Questions

- What is a remix? Give a definition of the different types of remix along with some examples.

- How can the concept of remix be applied to other forms of knowledge and expression beyond music?

- What is the purpose of copyright law? How does the concept of remix contradict the underlying principles of copyright?

- In what ways has remix shaped human history? Why did remix culture emerge so strongly in the twentieth century? What were some of the factors that facilitated its advancement?

- Explain the remix controversy. What are some of the important arguments for and against remix?

- Why is the concept of “ownership” and “originality” so complex? How does digital media further complicate these ideas?

- Explain what copyright is and how a work gains copyright protection. What are the three elements that must be in place for a work to be copyrighted?

- What are some examples of works that can be copyrighted? What works can’t?

- Explain what fair use means and what the standards are for deciding whether copying a work is considered fair use.

- How does a Creative Commons license extend permission to users beyond a traditional copyright?

Sources

The Art of Noise. “History.” TheArtOfNoiseOnline, 2017, https://theartofnoiseonline.com/The-Art-of-Noise.php.

BBC. “Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven Copyright Battle Is Finally Over.” BBC.com, 5 Oct. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-54423922.

Booker, Christopher. “How One Artist Put a New Spin on Mashing Up New and Old Music Tracks.” PBS.org, 23 Apr., 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-one-artist-put-a-new-spin-on-mashing-up-new-and-old-music-tracks#:~:text=For%20the%20last%2020%20some,album%20with%20fully%20licensed%20samples.

Collins, Bryan. “What is Fanfiction? 5 Types of Fanfiction.” BecomeAWriterToday, 26 Sept. 2022, https://becomeawritertoday.com/what-is-fanfiction/.

Copyright Advisory Office. “Fair Use Checklist.” Columbia University Libraries, 14 May 2008, https://copyright.columbia.edu/content/dam/copyright/Precedent%20Docs/fairusechecklist.pdf.

Copyright Alliance. “What Is the Purpose of Copyright Law.” CopyrightAlliance.org, 2023, https://copyrightalliance.org/education/copyright-law-explained/copyright-basics/purpose-of-copyright/.

Creative Commons. “What We Do.” CreativeCommons.org, n.d., https://creativecommons.org/about/.

Daniels, C. Wess. “Remix Culture and the Church.” GatherlingLight.com, n.d., https://www.gatheringinlight.com/2011/03/04/remix-culture-and-the-church/.

Ellis, Emma Grey, “Want to Profit Off Your Meme? Good Luck If You’re Not White.” Wired, 1 Mar. 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/03/on-fleek-meme-monetization-gap/.

Ferguson, Kirby. “Embrace the Remix.” TED, 2012, https://www.ted.com/talks/kirby_ferguson_embrace_the_remix/transcript.

———. “Everything Is a Remix.” EverythingIsARemix, 24 Mar. 2023, https://www.everythingisaremix.info/.

Galbraith, David. “There Is No Such Thing as Invention.” Medium.com, 7 June 2013, https://medium.com/i-m-h-o/there-is-no-such-thing-as-invention-30f0adc336ee.

Gaylor, Brett. RIP! A Remix Manifesto. National Film Board of Canada, 2008, https://www.nfb.ca/film/rip_a_remix_manifesto/.

Goodreads. “Mashup Books.” Goodreads.com, n.d., https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/mashup.

Harvard University. “Copyright and Fair Use.” Harvard University, 16 Feb. 2023, https://ogc.harvard.edu/pages/copyright-and-fair-use#:~:text=Fair%20use%20is%20the%20right,law%20is%20designed%20to%20foster.

Joo, Thomas W. “Remix without Romance.” Connecticut Law Review, 138. Retrieved from https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/138/.

Khanna, Derek. “50 Disney Movies Based on the Public Domain.” Forbes, 3 Feb. 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/derekkhanna/2014/02/03/50-disney-movies-based-on-the-public-domain/?sh=1995b56f329c.

LaFrance, Adrienne. “When a ‘Remix’ Is Plain Ole Plagiarism.” The Atlantic, 3 May 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/05/the-indignities-of-remix-culture/525129/.

Lagioia, Stephen. “The 10 Funniest Family Guy Spoof Episodes (According to IMDB).” ScreenRant, 3 Dec. 2019, https://screenrant.com/family-guy-funniest-spoof-episodes-imdb/.

Lankshear, Colin, and Michele Knobel. “Lankshear and Knobel Remix Lessig.” NewLearningOnline.com, 2008, https://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-1/lankshear-and-knobel-remix-lessig.

Lessig, Lawrence. “Re-examining the Remix.” TED, n.d., https://www.ted.com/talks/lawrence_lessig_re_examining_the_remix#t-573398.

———. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Penguin Press, 2008.

Murray, Ben. “Remixing Culture and Why the Art of the Mash-Up Matters.” TechCrunch, 22 Mar. 2015, https://techcrunch.com/2015/03/22/from-artistic-to-technological-mash-up/.

Navas, Eduardo. “Remix Defined.” RemixTheory, n.d, https://remixtheory.net/?page_id=3.

O’Brien, Jon. “Madonna’s 20 Top Remixes of All Time.” Billboard.com, 22 June 2022, https://www.billboard.com/lists/madonna-remixes-best-all-time-songs/.

Open AI. “Introducing ChatGPT.” OpenAI, 30 Nov. 2022, https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

OpenSource.com. “What is Open Source?” RedHat Inc, 2023, https://opensource.com/resources/what-open-source.

Rogers, S. A., “Art Remix: 26 Modern Takes on Famous Historical Paintings.” WebUrbanist, n.d., https://weburbanist.com/2011/11/07/art-remix-26-modern-takes-on-famous-paintings/.

Rostama, Guilda. “Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma.” WIPO Magazine, June 2015, https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2015/03/article_0006.html.

Roy, Nilanjana S. “The Panchatantra: The Ancient ‘Viral Memes’ Still with Us.” BBC.com, 17 May 2018, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180517-the-panchatantra-the-ancient-viral-memes-still-with-us.

Sayre, Eleanor C. “Generative Writing: How to Make the First Draft of Your Research Paper.” Zaposa.com, 18 Aug. 2023, https://handbook.zaposa.com/articles/generative-writing/index.html.

Simmonds, Ross. “The Disney Strategy: Why You Should Take Old Ideas and Remix Them.” Medium.com, 11 Dec. 2019, https://medium.com/@thecoolestcool/the-disney-strategy-why-you-should-take-old-ideas-remix-them-970102dee970.

Sulem, Matt. “The 25 Best ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic Parody Songs.” YardBarker, 19 Jan. 2022, https://www.yardbarker.com/entertainment/articles/the_25_best_weird_al_yankovic_parody_songs/s1__30317705.

SuperSummary. “Parody.” SuperSummary, n.d., https://www.supersummary.com/parody-in-literature-definition-examples/.

Tozzi, Christopher. “For Fun and Profit: A History of the Free and Open Source Software Revolution.” MIT.edu, 2017, https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/3528/For-Fun-and-ProfitA-History-of-the-Free-and-Open.

Trammell, Kendall. “6 Mickey Mouse Facts You Probably Didn’t Know.” CNN.com, 18 Nov. 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/18/entertainment/mickey-mouse-fun-facts-trivia-trnd/index.html.

University Libraries, University of North Texas. “Copyright Quick Reference Guide.” University of North Texas, 28 Oct. 2022, https://guides.library.unt.edu/SCCopyright/basics#:~:text=The%20three%20basic%20elements%20of%20copyright%3A%20originality%2C%20creativity%2C%20and%20fixation,-There%20are%20three.

U.S. Copyright Office. “Chapter 1: Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright.” Copyright.gov, n.d., https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#107.

———. “Circular 33: Works Not Protected by Copyright.” Copyright.gov, Mar. 2021, https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ33.pdf.

———. “Copyright in General (FAQ).” Copyright.gov, n.d., https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-general.html#:~:text=Copyright%20is%20a%20form%20of,both%20published%20and%20unpublished%20works.

———. “Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17)” Copyright.gov. N.d., https://www.copyright.gov/title17/.

U.S. Supreme Court. “Feist Publications Inc., v. Rural Tel. Ser. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).” Justia, n.d., https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/499/340/.

Vanderbilt University Writing Studio. “Invention (aka Brainstorming).” Vanderbilt.edu, 17 July 2023, https://www.vanderbilt.edu/writing/resources/handouts/invention/ .

Vickery, Jacqueline Ryan. “Mapping the Affordances and Dynamics of Activist Hashtags.” Paper presented at AoIR 2017: The 18th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers. Tartu, Estonia: AoIR. https://spir.aoir.org/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/10205.

Williams, Apryl. “Black Memes Matter: #LivingWhileBlack with Becky and Karen.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 4, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120981047.