12 Best Practices for Digital Writing

It’s probably not surprising that younger generations—millennials and iGens—are more likely to use and have a more intuitive understanding of technology than older generations. According to a study from the Pew Research Center, millennials are ahead of other generations when it comes to owning a smartphone (93%), using the internet (nearly 100%), and subscribing to social media (86%) (Vogels). Other studies report equally high numbers for Gen Z, also known as the iGeneration (Dorsey; Treatt), a group that is often assumed to be more tech savvy than other people because of the significant amount of time that they spend on digital devices. However, exposure to technology doesn’t necessarily enhance a person’s functional digital literacy—their ability to use a wide range of platforms effectively. In fact, a recent WorkLife article asserts that it’s often a misconception that younger people are innately better at technology (Pickup). In referencing a 2022 study by HP Inc., Oliver Pickup notes that 20% of employees between the ages of 18 and 29 felt “judged” when they experienced technical issues at work: “While young professionals may be more accustomed to digital environments, and certainly social media platforms, this doesn’t always carry over to professional tools,” said Debbie Irish, head of the Human Resources Department for HP in Ireland and the UK (qtd. in Pickup). Irish goes on to assert the importance of training, especially for younger professionals who don’t have the same experience with specific platforms and have less self-confidence to ask for help. Another study by the World Economic Forum reports that less than half of young employees have the digital skills they need to be successful, and many employers don’t offer the type of training that would help raise their skill level (Moritz and Stubbings).

While it’s impossible to prepare beforehand for every possible digital tool you might encounter—either academically or professionally—it is possible to cultivate a problem-solving mindset that allows you to adjust to new technologies that you encounter and figure out the most effective ways to use them to meet your specific purposes. Jill Castek et al. define digital problem-solving as the “nimble use of skills, strategies, and mindsets required to navigate online in everyday contexts, including the library, and use novel resources, tools, and interfaces in efficient and flexible ways to accomplish personal and professional goals” (2). This is a very broad definition that encompasses several different kinds of skills: finding useful information relevant to a particular topic, evaluating the credibility of information, learning how to use various technologies, and being able to discern which technology or platform is most appropriate in a given situation, troubleshooting problems as they arise with an attitude of confidence and patience.

In fact, one key cognitive dimension of digital problem-solving relates to a person’s ability to self-regulate, which is the mental process a person goes through when they are solving a problem or working to complete a task. It’s the ability to identify your goals, understand the steps that are involved in working toward those goals, and monitor your progress along the way so that you know when it’s time to move on to the next step. Castek et al. also assert the need to move beyond the cognitive dimensions of digital problem-solving to also include the “affective motivational domains” (1). In other words, they are interested in understanding how a person’s goals drive their use of technology and how their attitudes toward technology affect their problem-solving abilities. Someone with strong digital literacy skills might not always already know how to accomplish specific tasks. The real skill is in knowing how to apply what they already know to new situations, how to find the solutions they are looking for, how to imagine the creative possibilities of a specific tool to help them reach certain goals, and how to apply critical thinking and rhetorical insights to their everyday use of technology.

Like you might expect, the best practices for learning a new technology revolve around open-mindedness, curiosity, and knowing how to utilize resources to get the help you need. Obviously, knowing how to look up information on YouTube is a big help for many of your technology issues. Chances are that experts in a particular field or the creators of a particular platform have put how-to videos on YouTube to help novice (and even more advanced) users work through specific problems or tasks. For instance, SquareSpace is an increasingly popular platform for putting together a website, and there are a number of YouTube videos that walk new subscribers through how to set up their account and how to use the various tools. Similarly, there are numerous tutorials for Photoshop, InDesign, and even word processing applications like Microsoft Word and Google Docs. Using YouTube videos and also resources available online can make a huge difference when it comes to learning a new technology or troubleshooting specific problems. Other best practices are pretty obvious: Be willing to ask for help. Be patient with yourself as you encounter challenges. Give yourself plenty of time to do research and to practice with the platform.

As we’ve stressed in the previous two units of this textbook, there is an important difference between knowing how and knowing why—utilizing deeper critical and rhetorical thinking to understand your audience, your underlying communication goals, the affordances and constraints of a particular technology, and the underlying ideologies and moral consequences of using specific technologies. For instance, at the time of this writing, the ChatGPT language model has stirred up quite a bit of conversation about the opportunities it provides to create marketing content, write academic papers, and compose more creative pieces like songs and poetry (OpenAI). It seems pretty easy to use ChatGPT. You pose the question and then it crafts a response based on information from its databases. But a more critical perspective looks deeper into the moral consequences of having artificial intelligence do our writing for us. A rhetorical perspective would understand the limitations of ChatGPT when it comes to inaccuracies as well as the more subtle nuances of audience and purpose.

The point is that functional literacy works in tandem with critical and rhetorical literacies in order to make the most effective use of technology. This chapter, in particular, focuses on best writing practices for digital platforms, and it does so from a rhetorical perspective, focusing on the cognitive habits and information-gathering processes of the audience to inform the way that online texts are written. The same principle of knowing why applies to the concept of digital writing practices. It’s not that difficult to create a website, to subscribe to a social media account and post messages, or to write text messages and emails. Most people know how—or they could easily find out how—to do these things. The real skill comes in knowing why one platform is more appropriate for a given message than another or why specific writing strategies might be more effective with a particular audience than others. While it’s easy to post a blog article, you probably know that there are a lot of poorly written blog posts available online that don’t follow best digital writing practices and don’t consider the needs and perspectives of the audience. As we move into this final unit of the textbook, we’ll unpack some of the more “basic” digital writing strategies that are applicable to most online platforms, and as we move forward into the remaining chapters, we’ll drill down into specific genre conventions or different platforms and explore more technical aspects of writing and publishing in online spaces.

Learning Objectives

- Understand how functional literacy relates directly to critical and functional literacy.

- Learn how readers evaluate and process information that they encounter online.

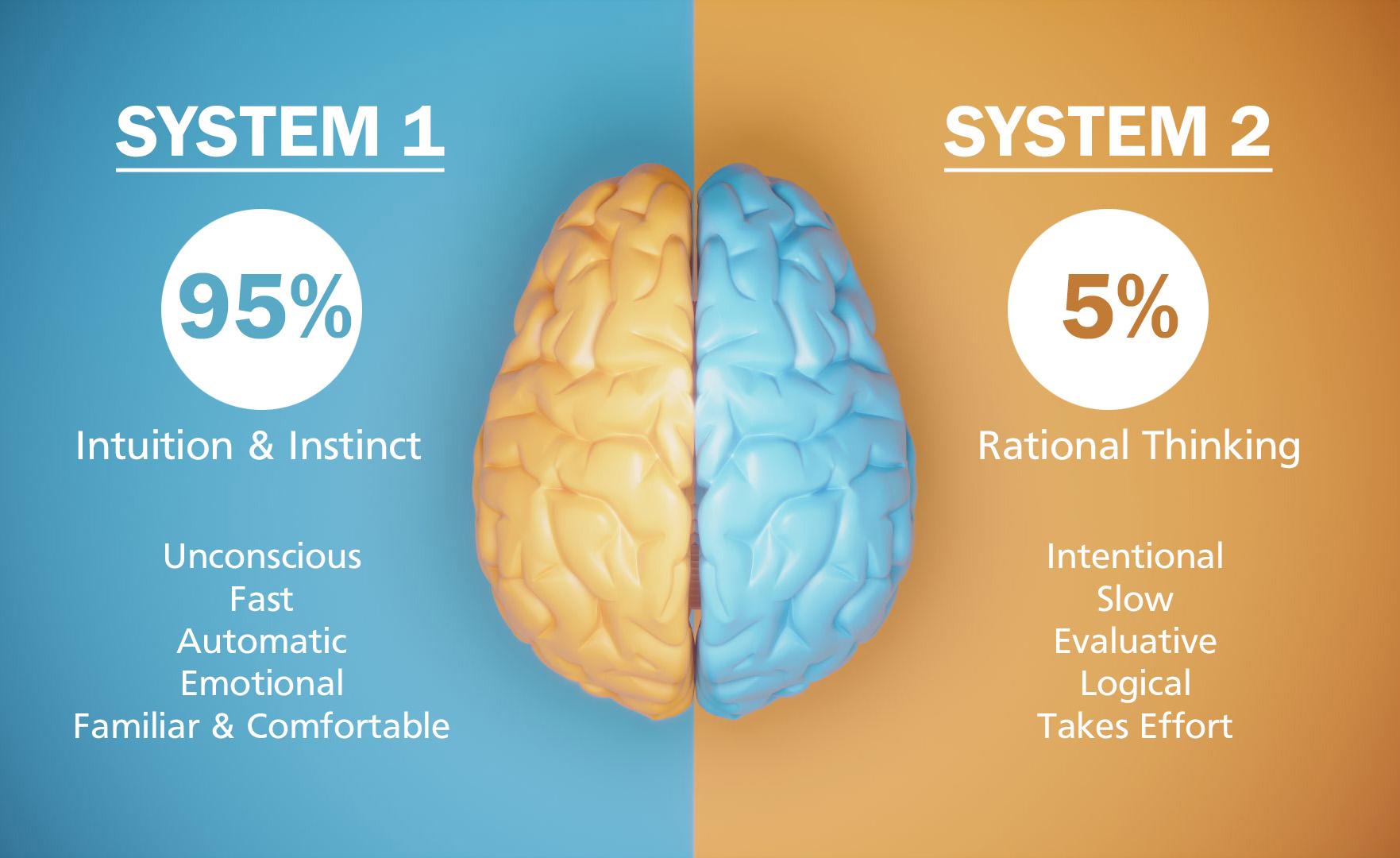

- Understand System 1 and System 2 thinking and the features that distinguish each one.

- Consider how specific writing strategies can be used to engage readers’ attention.

- Learn best practices for clear writing that helps readers quickly and easily understand your main ideas.

- Learn how to be concise.

- Understand what it means to have a professional tone and how it can be used to enhance credibility.

- Learn the principles of effective social media monitoring.

- Learn to be direct with a call to action at the end of your messaging.

System 1 and System 2

As you already know, good writing is reader-centered, considering the needs, perspectives, and expectations of the intended audience. In fact, all of your choices in a particular message should (ideally) enhance the audience’s understanding and engagement, which in turn, increases their likelihood of responding favorably to your message, either by seeing your perspective on a given topic or taking some sort of action. In digital writing, that means that you must also consider your readers’ thought processes, which begins the moment that they encounter your message and make the split-second decision to read it more carefully or move on to something else. The reality is that readers are pretty impatient when it comes to their reading habits. As we’ll see in this section, most people bounce away from a message if they don’t immediately see what they are looking for. And because users are constantly bombarded with digital messaging, they are more easily distracted.

To really capture and hold people’s attention, you have to be strategic with the way that information is presented, and this is where it will be helpful to understand System 1 and System 2—“fast” thinking and “slow” thinking. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes the two types of thinking that drive people’s daily activities and decision-making. System 1 thinking is “fast” thinking. It’s impulsive and makes quick decisions based on habits and first impressions. Kahneman describes System 1 as “operating automatically and quickly with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control” (20). System 1 thinking is also typically based on emotional responses and decisions that are comfortable or familiar. Unfortunately, System 1 is almost always running. It guides most of our decisions throughout the day, which allows us to prioritize tasks and conserve time and energy.

A good way to describe System 1 thinking is to think about your daily routine. Most of us have a schedule that we follow from one day to the next or from one week to the next, and once we are familiar with that schedule, we can almost run on autopilot to go from one task to the next. Driving to work or school, for instance, is pretty routine for most people, and it doesn’t take a whole lot of critical thinking—at least not on a normal day with normal traffic and weather patterns. You don’t have to invest a whole lot of mental energy into the act of driving. In fact, many people sing along to music, have conversations, and think about other things entirely while they are driving, which means that when they arrive at their destination, they probably can’t recall the specific places where they had to stop at a red light or the moments when they decided to change lanes. They were on autopilot. The same thing occurs in the morning when you are getting ready for the day, when you order from your favorite restaurant, when you are making a meal that you’ve made lots of times before. The same is also true at a store when you are deciding between one product brand and another. You probably don’t put a lot of time into researching the pros and cons of each item. You probably make a snap judgment based on the information that is easily accessible, like the price or the packaging.

System 2, in contrast, is the more logical, critical-thinking process where you more deeply engage with a particular topic or event, carefully evaluate your options, and make choices that are grounded in evidence and reason. Kahneman says, “System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration” (21). He goes on to explain that people tend to associate themselves with System 2—“the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do” (21). The problem is that System 2 is lazy. It takes quite a bit more time and mental energy to engage meaningfully in a particular activity and to go through the intellectual task of taking in and evaluating information, and System 2 is reluctant to put in that kind of effort. Fortunately, it’s also not always necessary for you to engage System 2. The process of brushing your teeth (or deciding whether to brush your teeth) and making a selection from the dollar menu at McDonald’s aren’t activities that require a lot of deep, critical thinking.

However, many activities do require System 2 thinking. Kahneman explains, “When System 1 runs into difficulty, it calls on System 2 to support more detailed and specific processing that may solve the problem of the moment. System 2 is mobilized when a question arises for which System 1 does not offer an answer” (24). There are some obvious instances when this might occur. Take our driving example above, which is normally pretty routine and can be easily accomplished from System 1. However, if you run into a serious downpour, heavy traffic, or hazardous road conditions because of ice, then System 2 engages. You’d probably turn off your radio and avoid other distractions or conversations so that you can more fully “focus” on driving. Or if you pull up to the McDonald’s drive-thru and discover that they are out of the number-two combo meal that you always order, suddenly you have to look more carefully at the other options and weigh out your choices.

There are also instances when people probably should engage System 2 thinking, but they don’t because they don’t necessarily encounter an immediate problem. For instance, if you’re in a meeting or in a class, and you can get by with nodding along during the discussion without really listening to or trying to process or apply the information that is presented, then it’s possible that you might not engage System 2. Only when you sense that it’s necessary to engage System 2—maybe because there will be a test over the material presented in class or because you have to complete a project based on the information in the meeting—will you do so. In other words, if you perceive that the information is important or relevant in some way, then you will engage more deeply. But how and under what circumstances different people discern information as being important is wildly inconsistent. Some people will be more interested in the topic than others. Some people have better mental habits that allow them to plug in when others are talking. And so on.

Understanding people’s thought processes—System 1 and System 2—can significantly enhance your digital writing strategies. If your goal is to get readers to engage System 2, in which they engage with your message and think critically about the information that you are presenting, you have to first capture the attention of System 1, which is no easy task in today’s digital realm. According to the Nielsen Norman Group, which specializes in understanding the user experience and the types of information that creates positive user engagement, most web users will only stay on a page for 10 seconds if they don’t immediately see the “value proposition”—or the reason that the information provided is relevant and important to their needs. “The first ten seconds of the page visit are critical for users’ decision to stay or leave” (Nielsen, “How Long.”). That’s because they are operating in System 1 to quickly analyze the information provided. In System 1, a user might actively be looking for specific information or they might happen on a page that initially piqued their interest, but if they don’t immediately perceive that the information is relevant—based on the title, the pictures, a quick glance at topic sentences—then they will bounce away without engaging System 2. However, if their initial impression of the page is that it is relevant and interesting, then System 2 is mobilized, and they are likely to stay on the page for much longer to read and process the information provided.

The Nielsen Norman Group article ends with this key takeaway from their research: “To gain several minutes of user attention, you must clearly communicate your value proposition within 10 seconds” (Nielsen, “How Long”). Your message might not be relevant to everyone, but the people in your target audience must immediately discern that your message is relevant, interesting, and important in some way. The best practices identified in this chapter are geared toward just that—helping readers understand the value of your message so that they will engage their System 2.

Activity 12.1

Write a reflection about your own System 1 and System 2 thinking. In your daily routine, which tasks tend to fall under System 1 because they are automatic and require very little intentional thought? Which tasks require you to engage System 2, applying a deeper level of attention and critical thinking?

Now evaluate your System 2 thinking a little more. Under what circumstances do you tend to activate System 2 thinking? Are there moments when you should activate System 2 but you don’t? Are you too quick to dismiss information as irrelevant and unimportant?

When it comes to digital messaging, what type of information catches your attention? Think beyond the content itself to consider the structure and the overall approach to the message.

Be Clear

Given that a reader won’t engage System 2 unless they perceive that the information presented is relevant to their needs, you have to be as clear as possible to let readers know what the content is about and what they will gain from reading it—that is, the value proposition. Also, remember that System 2 is pretty lazy and that you only have a few seconds from the moment someone lands on your page to convey that value. If the language is difficult to understand or if the main idea of the page is buried somewhere in the fourth paragraph, readers won’t engage.

This section provides some basic strategies for making sure that your digital writing content is clear, but first, a quick reminder about rhetorical context. Many of the best practices listed in this chapter are helpful guidelines for a variety of digital texts, and they align with the audience’s expectations in most circumstances. However, what we’ve learned about rhetoric and the use of effective communication is that it’s highly contextual. It’s important for you to think clearly about your audience and their expectations for a given message. For instance, academic articles are often published on digital platforms, and in that case, the audience—with specialized knowledge in a given field—would expect the text to be long and more complex, with language that other people might not completely understand. Similarly, an email to colleagues in a particular department would likely rely on more technical language in order to communicate key ideas.

The point is that the writing must still be clear—easy to follow and with easily identifiable main ideas—but your approach to clear writing might be different from one context to the next, depending on your audience and also your message. We’ll talk more in-depth about genre selection and conventions in later chapters. While some of these best practices might be applied a little differently depending on the circumstances, the general principles are consistent. Below are important guidelines to make sure your writing is clear:

- Put the main idea of the text in your title. Many web genres have titles—blog posts, web pages, some social media ads, and emails. The very first thing that readers look at when deciding whether the information is relevant to them is the title, so don’t be cryptic or overly creative. A short, clear title that identifies the value proposition will be more effective in grabbing the attention of people in your target audience. For instance, a blog titled “10 Best Vacation Spots in Indiana” gives a very clear picture of what the article will be about. On the other hand, the title “Pack Your Bags” doesn’t immediately convey the main idea of the article and would be less likely to get the attention of readers, even those readers who might otherwise have been interested in the article. The title didn’t seem relevant to their needs.

- Use headings and subheadings. Especially for longer texts, breaking it up into smaller sections with headings and even subheadings can be a very effective way to help readers stay engaged and follow along with the main ideas. Once again, it’s important that headings be descriptive so readers have an idea of what the section will be about. Headings are especially common for blog articles and web pages, but they can also be effective for longer emails. Put headings in bold so they are easier to spot.

- Put the most important information near the beginning. It’s okay to hook readers into a longer blog article with a clever opener, but pretty quickly, the intro paragraph should identify the main idea. For shorter social media posts and emails, it’s usually best to lead with your main point in the very first sentence.

- Keep the language and sentence structure simple. That doesn’t mean that you have to “speak down” to your audience or craft overly simple sentences that are short and choppy. It does mean that you’d avoid jargon that might alienate or frustrate some people in your target audience. You’d also avoid consistently long, complex sentences that are difficult to untangle. Generally speaking, digital writing tends to be pretty conversational. Writing that is overly formal or advanced is not only more difficult to understand, but it doesn’t create emotional connections with readers and probably doesn’t communicate the type of brand that you are trying to build.

- Use precise language. A lot of beginning writers tend to be fairly vague in their writing, which always leaves lingering questions in the minds of readers and has less of an impact than writing that is more specific. Vague writing always invites the question “Can you be more specific?” For example, let’s consider a blog article about the importance of wearing a seat belt. If the article begins with a “recent” narrative in which the author was “severely injured” in a car accident because they weren’t wearing their seat belt, you probably have enough information to generally understand the main idea. However, you’d probably also want to know more about “how recent” the incident was and also what made the injury so severe. Similarly, if the blog cited “recent studies” about the efficacy of seat belts, you’d want to know which specific studies the author is referring to. While it’s probably not necessary to include every minute detail, good writing is always specific and uses language that is precise.

- Use hyperlinks. Adding hyperlinks to relevant information is an easy way to clarify information, build credibility, and point readers toward additional resources. So if a blog does mention a particular study or article, a hyperlink to that specific study gives readers a chance to read the study for themselves and understand how it supports a particular idea presented in the blog. All platforms are slightly different, but the idea of a hyperlink is that you aren’t breaking up text with a long URL. You select appropriate words and phrases within the text to become the hyperlink. Highlight those specific words, click the “insert link” icon, and then paste the URL of the outside web page into the dialogue box.

- Repeat keywords. No, we’re not talking about SEO yet. Repeating certain keywords and phrases that capture the main idea of the text will help readers follow along. Those keywords would obviously appear in the title, and then when it’s repeated in the introduction and in subsequent paragraphs, it helps readers to make important connections and see how one idea builds on the next. Obviously, you don’t want to be overly redundant, but you do want to be mindful of your keywords and how they can be used to enhance readers’ understanding.

Be Concise

Another important best practice for digital writing is to be concise. Avoid long sentences and long blocks of text. You can probably resonate with the fact that large text blocks can be overwhelming and discourage readers from engaging with the text. In fact, most readers don’t actually read a web page word for word; they scan (Nielsen, “How Users Read”), only taking in about 20% of the information on the page (Nielsen, “How Little”). Finding ways to tighten up your sentences and organize information into smaller sections improves readability and helps readers persist through the main points of your message.

- Condense information. This is often easier said than done, but many times, writers include unnecessary details and information that could easily be cut and still convey the same overall meaning. You’d also avoid redundancies, find ways to shorten wordy sentences, and eliminate “filler” words that don’t add meaning. The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has some excellent suggestions for condensing long sentences. Chapter 18 of this textbook also provides useful strategies.

- Organize information into chunks. While paragraphs in print publications might be fairly long (sometimes up to 10 or more sentences), paragraphs on digital writing platforms are short—around two to five sentences. In addition to keeping paragraphs short, longer articles are also broken down into different sections with clear headings. This is called “chunking” your content, and it makes the key ideas easier to follow. Limit the length of each section to just a few paragraphs.

- Use hyperlinks. Once again, hyperlinks can be a helpful tool to keep texts short. Instead of elaborating on specific details from a separate web page, creating a hyperlink to that page allows readers to find the information for themselves and eliminates clutter in your message.

- Use bullets. Another strategy for increasing the readability of your texts is to create bulleted lists where appropriate. Since readers tend to scan long paragraphs, often missing the key information embedded, the bulleted list makes it easier for readers to quickly see all of the key points in a list.

- Write in an active voice. Active voice puts the emphasis on the person or thing that is doing the action, whereas passive voice emphasizes the person or thing that is acted upon. Active voice tends to be shorter and easier to understand. For instance, “Jenny made a cake last night and then ate a big piece before bed” is in active voice and it puts the focus on Jenny and her actions. It’s much easier to understand than the passive version: “The cake was made last night by Jenny, and a big piece was eaten by Jenny before she went to bed.” It’s always better to use active voice when you can.

- Eliminate “be” verbs when possible. Often “be” verbs (am, is, are, was, were, be, being, been) are wordier and less meaningful than alternative verbs and phrases. For instance, instead of saying, “We will be eating dinner at 5 p.m.,” the sentence “We will eat dinner at 5 p.m.” is slightly shorter and creates a stronger verb more relevant to the main idea of the sentence. Here are a number of other strategies for eliminating “be” verbs, created by Beacon Point.

Be Professional

It probably goes without saying that you want your content to come across as professional. That doesn’t mean that it has to be stuffy or boring. It does mean that the writing would demonstrate your maturity and understanding of writing strategies that build your credibility and invite readers to engage. While there might not be a set definition of what makes writing “unprofessional,” the effect is that it comes across as self-centered, unfocused, or lazy. For instance, writing that doesn’t seem to have a clear main point, meandering from one topic to the next and interweaving personal stories and opinions, might be okay for a personal journal or diary, but it would come across as unprofessional on a web page because it isn’t considerate of readers’ needs and expectations. Similarly, writing that is filled with grammar and punctuation errors would come across as unprofessional because it seems lazy—and it makes it much harder to read a message. In general, best practices for professional writing include the following:

- Avoid slang. While there might be occasion (rhetorically speaking) to use slang in a blog article or social media post, you’d probably want to avoid it most of the time—especially words and phrases that are only familiar to a narrow group of people. Using slang alienates some readers who don’t know the meaning of the slang terms. It also might not be appropriate for articles or web pages with a more professional purpose.

- Avoid language that is inappropriate or offensive. Always. This is a hard and fast rule. Cuss words and other language that comes across as rude, sexist, racist, homophobic, ageist, and so on should always be avoided, even if you’re writing a simple text message to a friend, and the inside joke seems harmless enough. You never know who will see that message or how your language might be taken out of context.

- Stick to your purpose. Stay focused on one clear main idea and the evidence and reasoning that helps to develop that idea. Personal asides and other tangents can be very frustrating to readers who are looking for specific information.

- Be respectful. Part of being professional is being accommodating to different ideas and perspectives and to treat alternative viewpoints with respect. Posts or emails written in anger or with little regard for differing opinions will come across as childish and self-centered. That doesn’t mean that you must always agree with other people or that you can’t verbalize your own position on a topic, but your writing should invite calm, reasoned engagement from other perspectives instead of being dismissive or condescending.

- Proofread. Correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling can go a long way to build credibility. That’s not to say that every single comma must be in the correct spot or that you’ll lose readers’ attention if you have one fragment sentence, but writing that is full of errors is hard to read, and it gives the impression that you didn’t put as much time and energy into the message as you could have.

Be Engaged

Successful digital writing that truly engages audiences and develops a strong brand demonstrates a level of author engagement—your effort to be involved in conversations with people as they respond to your content. This is called “monitoring,” and though it might not be part of your original content, the way that you respond to comments, questions, and complaints becomes part of a public thread that other people can see, and it can have a significant influence on their perception of you and your brand.

At a minimum, monitoring means that you keep tabs on and respond appropriately to comments on your digital channels—web pages, blog articles, social media accounts—which helps you understand how your audience is reacting to your content and maintain a positive brand identity. The advantage of so many of these platforms is that they offer the opportunity for readers to participate in the conversation and for writers to engage with their audience on a deeper level. Even simple metrics like the number of views, shares, and likes help you understand how people are responding to your message, but more than that, you should pay attention to the comments that people post—this includes positive feedback as well as questions and even negative comments. This allows you to offer additional information and to try to understand and address the more negative comments. Below are a few best practices for monitoring audience engagement:

- Respond thoughtfully to at least some of the positive feedback. You might not be able to respond to everyone, but having a presence in the discussion thread lets people see that you are engaged in the conversation.

- Provide complete and specific answers to relevant questions.

- Be respectful as you engage with negative comments. You might not be able to come to an easy resolution in every circumstance, but your effort can go a long way toward building trust and goodwill, if not with that specific person then at least with other people who read the discussion thread.

- Avoid the urge to delete every negative comment. That makes it seem like you are hiding something or unwilling to engage with anyone with a different perspective.

- Delete comments that are offensive in nature. This includes comments with profanity as well as comments that are threatening or that resort to name-calling. In some instances, you might even screenshot the post before you delete it, so you can report it to the platform administrators.

- Consider ways to monitor discussions about your brand in other places. This might include customer reviews, posts where you are tagged in a photo, brand hashtags, and @ mentions.

Be Direct

One final suggestion for many of the posts that you write is to be direct. Often there is a particular way that you will want audiences to respond, especially if your post is related to some sort of campaign or marketing strategy. You might want your audience to click a link to get more information, to sign up to receive your newsletter, to purchase a particular product, to schedule a meeting, or to go to your website. Even when you send an email to colleagues or clients, there is often a response that you are looking for—maybe a deadline that a project should be completed or the answer to a question that you have. Whatever it is that you want the audience to do as a result of your message, be direct about it. Most blog articles, web pages, and even emails end with a CTA (call to action) that tells readers exactly what you want them to do next and gives them all of the information they need to take that action. You’re much more likely to get the response you are looking for with clear and direct instructions.

Activity 12.2

Social media platforms are full of posts that you can use to critique and improve your own writing. Find a social media post or blog article that relies heavily on written content and evaluate it for the best practices identified above. The exercise will probably work better if you identify content written by a company or organization as opposed to an individual on a personal account.

Now review the content of the post you’ve selected. Is it clear? Concise? Professional? Engaged (in the discussion thread)? Direct about CTAs? What are the post’s strengths? What could still be improved? Write a revised, improved version of the post that follows each of the best practices.

Discussion Questions

- The beginning of the chapter noted that functional literacy works in conjunction with rhetorical and critical literacy. What does this mean? How is functional literacy (learning how) informed by both critical and rhetorical literacy?

- Which elements of the rhetorical situation seem especially relevant to this section on best practices for digital writing? Why?

- What is System 1 thinking? How does it work? Give some examples.

- What is System 2 thinking? How does it work? Give some examples.

- In what circumstances does System 2 activate? In particular, how can digital writing strategies be used to engage readers’ System 2 thinking?

- What is the value proposition? Why is it important to be clear and upfront about the value proposition of a text? Can you find examples online where this is done well?

- What are some other important strategies for making sure that your message is clear and easy for your intended audience to understand?

- What are some key strategies for concise writing?

- In the context of this chapter, what does “professional” writing mean? Why is it important?

- What is social media monitoring and why is it important? What are some ways that an author can effectively engage with their audience?

- What is a CTA, and why is it important to include in digital messaging?

Sources

Beacon Point. “8 Strategies to Eliminate ‘Be’ Verbs.” Bacon Point, 9 May 2018, https://beaconpointservices.org/8-strategies-to-eliminate-be-verbs/.

Castek, Jill, et al. Defining Digital Problem-Solving, 2018, https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=digital_equity_toolkit.

Dorsey, Jason. “Gen Z and Tech Dependency: How the Youngest Generation Interacts Differently with the Digital World.” JasonDorsey.com, n.d., https://jasondorsey.com/blog/gen-z-and-tech-dependency-how-the-youngest-generation-interacts-differently-with-the-digital-world/.

HP, Inc. “Are We There Yet?” HP.com, 19 Aug. 2022, https://h20195.www2.hp.com/v2/getpdf.aspx/4AA8-2370EEW.pdf.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux: New York, 2011.

Moritz, Bob, and Carol Stubbings. “Global Youth Expect Better Access to Skills. Here’s How Businesses Can Respond.” World Economic Forum, 15 July 2022, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/youth-workers-skills-access-business/.

Nielsen, Jakob. “How Little Do Users Read?” Nielsen Norman Group, 5 May 2008, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-little-do-users-read/.

———. “How Long Do Users Stay on Web Pages?” Nielsen Norman Group, 11 Sept. 2011, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-long-do-users-stay-on-web-pages.

———. “How Users Read on the Web.” Nielsen Norman Group, 30 Sept. 1997, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-users-read-on-the-web/#:~:text=People%20rarely%20read%20Web%20pages,out%20individual%20words%20and%20sentences.&text=Share%20this%20article%3A,read%20word%2Dby%2Dword.

OpenAI. “ChatGPT: Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue.” OpenAU.com, 30 Nov. 2022, https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/.

Pickup, Oliver. “Gen Z Workers Are Not Tech-Savvy in the Workplace—and it’s a Growing Problem.” Worklife.news, 14 Dec. 2022, https://www.worklife.news/technology/myth-buster-young-workers-are-not-tech-savvy-in-the-workplace-and-its-a-growing-problem/.

Treatt. “Introducing the iGeneration.” Treatt.com, 2 Dec. 2020, https://www.treatt.com/news/introducing-the-igeneration.

Vogels, Emily A. “Millennials Stand out for Their Technology Use, But Older Generations also Embrace Digital Life.” Pew Research, 9 Sept. 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/09/us-generations-technology-use/.

The Writing Center. “Writing Concisely.” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2023, https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conciseness-handout/.