5 Privileged Spaces

As we continue our critical investigation of digital technologies and practices, it’s important to consider the many ways that social inequalities are perpetuated in digital spaces. In fact, the word “critical” has a deeper meaning that goes beyond thinking carefully about a topic from different perspectives. It can also be applied more specifically to the examination of power structures within a particular culture and how systems are often used to reinforce the unequal distribution of benefits among different groups of people. In fact, many issues that you might debate with someone are really about power: Who should have the power to make and enforce decisions? Which perspectives, behaviors, and people should be prioritized? Which ones should be subordinated or ignored?

This type of critical analysis requires constant self-awareness and self-discipline to identify flawed thinking, uncover “blindspots” and “self-delusions,” and apply different modes of thinking (e.g., scientific, social, economic, moral) in order to reach a conclusion that will inform personal growth and positive action. It also requires repetition, making you examine the same issue over and over again as you encounter it in different contexts. This is perhaps the most challenging—and important—aspect of critical thinking: adopting a growth mindset that remains open to authentic self-analysis and revision, even (and especially) when it’s an issue in which you struggle to engage with opposing perspectives.

What does critical thinking have to do with social justice? Everything. Your actions are driven by your values and beliefs—your ways of thinking about the world. We all fall into habits of mind based on personal perspectives and social norms, which guide our daily interactions and routines; more often than not, we’re not fully conscious of where our underlying beliefs came from, how they align (or not) with our core values, and what consequences they have on other people. We might overlook or ignore how our actions perpetuate the status quo in big and subtle ways. In contrast, critical thinkers do the difficult work of asking questions, wrestling with contradictions and complications, and silencing the natural feelings of defensiveness and dismissal that emerge when existing assumptions are challenged. The Foundation for Critical Thinking describes critical thinkers like this:

They work diligently to develop the intellectual virtues of intellectual integrity, intellectual humility, intellectual civility, intellectual empathy, intellectual sense of justice and confidence in reason. They realize that no matter how skilled they are as thinkers, they can always improve their reasoning abilities and they will at times fall prey to mistakes in reasoning, human irrationality, prejudices, biases, distortions, uncritically accepted social rules and taboos, self-interest, and vested interest. They strive to improve the world in whatever ways they can and contribute to a more rational, civilized society.

It’s not about guilt. As we studied in chapter 3, everyone has their own terministic screen that shapes the way that they interpret information. Being a critical thinker means that you examine your perspectives and personal biases and that you try your best to understand other viewpoints and experiences that are vastly different from your own.

When it comes to digital technology, this means looking beyond the utopian perspective of technology as being always inherently beneficial for everyone. In fact, contrary to what many people believe, digital technology has not leveled the playing field for minority groups. While it is true that the web was originally intended to be a marketplace of ideas where lots of different voices could be heard, the reality is that the internet has reinforced social inequalities based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education level, age, and so on. Minority groups don’t have equal access to digital technologies, which is particularly true if we consider the different types of access. In his book Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground, Adam Banks identifies five types of access: (1) material access, “equality to the material conditions that drive technology use or nonuse” (41); (2) functional access, having “the knowledge and skills necessary to use technological tools effectively” (41); (3) experiential access, “access that makes the tools a relevant part of [the users] lives” (42); (4) critical access, “understandings of the benefits and problems of any technology well enough to be able to critique, resist, and avoid them when necessary as well as using them when necessary” (42); and (5) transformative access, “genuine inclusion in technologies and the networks of power that help determine what they become, but never merely for the sake of inclusion” (45).

Indeed, minority groups struggle with multiple levels of “access,” and as our culture becomes more reliant on digital technologies for social (Helsper and Deursen), educational (Human Rights Watch), professional (Townsend), and financial (Sridhar) activities, the digital divide continues to grow (Li). What’s more, when they are online, minorities continue to experience different forms of discrimination, such as exclusion, stereotyping, and hate speech intended to belittle and discourage (Nguyen et al.). As you probably know already, hate speech is often more aggressive when done online because people can reach a wider audience; navigate in an echo chamber of other like-minded users who are unlikely to challenge in-group bias; and hide behind keyboards, pseudonyms, and anonymous avatars.

This chapter takes a critical look at the social inequalities that exist within—and are often made worse because of—digital technologies and online spaces. First, we will define what “privilege” is and how it functions in different contexts. Then we’ll look at some of the social consequences of inequality and how the status quo is perpetuated in digital spaces, even amid technologies that are intended to promote positive change. Finally, we’ll look at some practical tools you can use to evaluate the digital spaces you visit/support as well as your own digital messaging so you can act as a positive force in the fight for social justice.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the different types of “access” that relate to digital technologies.

- Consider the numerous advantages that come with access as well as the ongoing disadvantages for people who don’t have access.

- Have a clear understanding of what “privilege” means and the tangible effects that it can have for those with and without privilege.

- Understand what the digital divide is and the different factors that relate to a person’s ability to access digital spaces.

- Learn about the different ways that some groups of people are marginalized in online spaces. Consider the ways that this divide relates to other forms of privilege.

- Learn critical literacy tools that will enable you to be more aware of and have a positive influence on discriminatory policies and exclusionary messages.

Defining Privilege

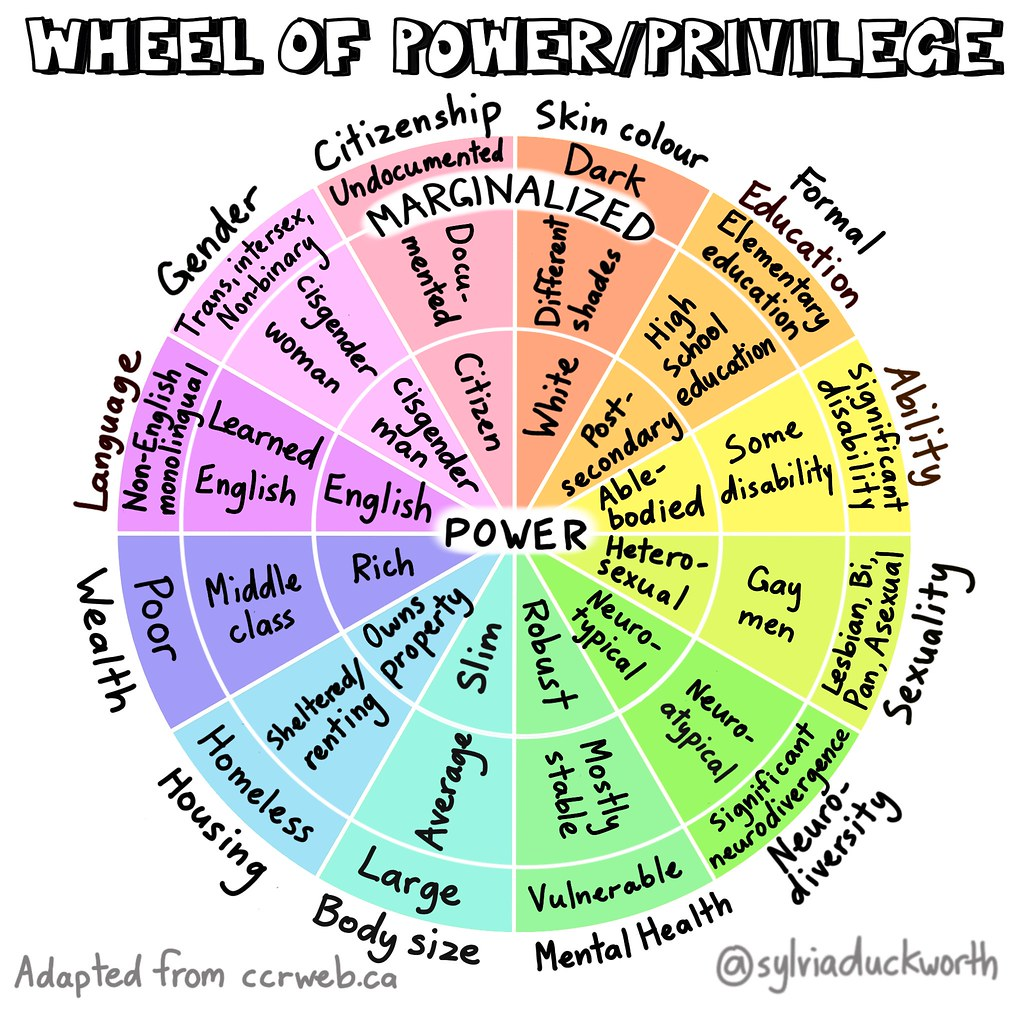

Unfortunately, the word “privilege” has become politicized in recent years (Boyers). Some people automatically shut down or become defensive when they hear the word, perhaps because it is sometimes used to invoke guilt or to obfuscate other significant experiences and qualities that make people unique. The point of discussing it here in this chapter is not to reduce people’s rich human experiences and complex characteristics to a single attribute (e.g., gender, skin color, economic status), and it’s certainly not intended to create feelings of guilt or defensiveness. The purpose is to bring awareness to the fact that most people have varying types of privilege depending on their social location. They experience certain benefits that other groups don’t have access to because of lingering discriminatory practices and consequences. It’s helpful for you to consider how privilege (or lack thereof) in certain circumstances has had an effect on your life and the opportunities that you’ve experienced and to consider the consequences of privilege (or lack thereof) for other people who are different from you.

First, a quick definition is in order. According to a library guide at Rider University, privilege can be defined as “certain social advantages, benefits, or degrees of prestige and respect that an individual has by virtue of belonging to certain social identity groups.” The guide goes on to describe privilege that centers around qualities like race, class, religious affiliation, gender, education level, ability, sexuality, and so on. Everyone has a social location comprised of varying identities. To have privilege means that because of one or more of these attributes, you experience rewards and opportunities that other people don’t. In contrast, in some circumstances, you might experience discrimination or unequal access to rewards and opportunities based on one of these social markers.

Let’s look at a simple example: the world is clearly set up for people of average height. They are “privileged” because they experience automatic benefits based simply on this one physical characteristic. They can easily reach the pedals in their car. They can see over the person in front of them at a movie theater or concert. They can reach items on a top shelf at the grocery store or in their own closet. Their feet touch the ground when they sit in a normal chair. They can ride any roller coaster of their choosing at an amusement park. Socially, they fit more easily into conversations because they are at a similar eye level with other people. These are all things they take for granted because they are in a privileged position. The world is set up for them, and they don’t have to deal with the disadvantages of being short, which makes it easy to overlook. A short person, on the other hand, deals with the hassles every day of being short, which sometimes means they don’t get the opportunity to ride a particular roller coaster or sit comfortably in normal chairs. In other cases, it means they have to work harder than other people to reach the top shelf or operate a vehicle. They are probably well aware of the disadvantages they face every day.

A similar example happened just a few years ago at an academic conference in which a panel of speakers was positioned to sit in chairs across a platform in an auditorium. A series of tall steps led up to the platform, and one of the speakers who was walking with a cane had a very difficult time getting up the stairs to the platform. The venue was set up for—it was “privileging”—people who were able-bodied and could easily climb a couple of stairs. No doubt, the people who organized and set up the venue with the platform were also able-bodied. They in no way intended for this woman to feel excluded or inconvenienced in any way. They simply didn’t think about the problems that she would encounter because they didn’t encounter those problems themselves.

You can probably see where this is going. These are both poignant examples of privilege that give some groups of people—tall or able-bodied people—an advantage over others. Of course, short people can still drive a car just fine with a few accommodations, and once they are able to reach the ingredients they need off the top shelf in the grocery, maybe with the help of a clerk or a step stool, their short stature doesn’t have anything to do with the quality of the meal they might make when they get home. Similarly, the woman at the conference delivered an excellent presentation based on her expertise and years of study. However, in both cases, the short person or the disabled person had to work harder to overcome obstacles in order to participate in the same activities as other people. This is what privilege is, and it can be applied to lots of different circumstances: the poor family who can’t afford childcare for their children, the female employee who is always asked to make food for social events, the Black shopper who gets followed by store security.

This connects to digital technologies in profound ways. All digital technologies are designed by people with their own biases and blind spots, which in turn influences the way those technologies are designed and the experience that different users have. In the first chapter, we touched briefly on the idea of biased algorithms that serve dominant groups and further marginalize certain populations (Eubanks; Metz). That’s often because the technology is created by people in dominant groups, those who have multiple layers of privilege and aren’t accustomed to examining the world through a different lens. Take, for instance, the experience of Joy Buolamwini, who started an organization called the Algorithmic Justice League after realizing that the software she was using to develop a new “facial analysis technology” was racist. It would only work if she put on a white mask; it wouldn’t recognize her black face. She coined the term “coded gaze” to refer to “the priorities, preferences, and prejudices of those who have the power to shape technology—which is quite a narrow group of people” (Buolamwini). In other words, many technologies are designed in ways that further marginalize certain groups and reinforce the status quo.

To truly understand privilege and its consequences, it’s important to consider a few additional concepts:

- Having privilege doesn’t mean that someone hasn’t worked hard for the things they’ve received. As Allan Johnson explains in his book Privilege, Power, and Difference, “The existence of privilege doesn’t mean I didn’t do a good job or that I don’t deserve credit for it. What it does mean is that I’m also getting something that other people are denied, people who are like me in every respect except for the social categories they belong to” (21–22).

- Your social location doesn’t really say anything about you as a person. The color of a person’s skin, their gender, their economic status, and their education are all qualities that people have, but they don’t say anything deeper about a person’s personality, their values and beliefs, their hopes and dreams for the future, and so on.

- Privilege is also not the same as difference, though the two things are related. Again, Johnson helps shed light on the fact that difference, in and of itself, is not a bad thing. People are not naturally afraid of or repelled by difference: “The trouble is produced by a world organized in ways that encourage people to use difference to include or exclude, reward or punish, credit or discredit, elevate or oppress, value or devalue, leave alone or harass” (16). He goes on to explain how even the categories of difference are socially constructed as a way of creating labels and that these labels are used to “reduce people to a single dimension of who they are” for the sake of creating an “other.”

- The benefits of privilege are exponential (McCrann). Privilege means having advantages and resources on a daily basis to further your education, to obtain and maintain a career, to access job promotions, to develop a social support system, to take care of your own mental and physical health, and to pursue your interests and life goals. These things have a cumulative effect that puts someone in a greater position to reap more benefits. Something as simple as having the money for a tutor in middle school and high school would help a student learn study skills as well as important concepts that would elevate their GPA and test scores, help them get into more prestigious universities (perhaps with a scholarship), be successful in the academic program of their choosing, and be more likely to get a high-paying job in their given field, which leads to more financial benefits related to credit scores, material possessions, health care, retirement benefits, and so on. Yes, this is a simplified example. The ability to pay a tutor might not be the sole reason for all of this success, but it would be a condition of privilege that would correspond with other advantages, such as parents who are well-educated, a comfortable home that is conducive to personal learning and growth, networking and internship opportunities, or the money to pay for a prestigious college once accepted. It’s a complex network of advantages that facilitates continuing success. And for people who don’t have particular types of privilege, their educational, social, and financial losses are also exponential.

- Privilege is easy to ignore or explain away if you have it. As demonstrated in the examples above, someone who is benefiting from some sort of privilege isn’t likely to realize it. They aren’t actively or intentionally oppressing anyone; they are simply living their lives in systems that are created to put them at the center, which makes it difficult to recognize the disadvantages other people face. If you aren’t convinced, this Buzzfeed article has a long list of privileges that most people in first-world countries take for granted without giving a second thought to the significant personal benefits they provide or the reality that so many people around the world don’t share these same benefits (Sloss).

The challenge, of course, is to recognize your own privilege in different ways. The simple fact that you have the ability and the time to sit and read this text—perhaps for a college class—signifies that you have the privilege of furthering your education, of taking the time to nurture your own personal and professional interests, of working toward a degree that will greatly enhance your chances of obtaining a rewarding career and reaping the financial benefits. In these and probably other areas as well, you’ve had some advantages that other people haven’t because of previous and continuing privileges. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t work hard or take advantage of opportunities as they arise. It also doesn’t mean that you should feel guilty for your success. What it does mean is that you should pay attention to the way society is organized to benefit certain people, recognize your own privileged circumstances, and do what you can to effect positive change so everyone has equal access to opportunities and personal benefits regardless of differences.

Activity 5.1

Review this identity wheel (Scripps College) or something similar that will help you identify the different aspects of your own social location. Consider the areas in which you have privilege as well as the areas in which you don’t. Can you identify examples of the privileges and/or disadvantages that you’ve experienced because of these identity markers?

Once you are finished, share your list with someone else, preferably someone who is “different” from you in one of the categories. As they share with you, be attentive to and respectful of their perspectives. See if you can identify privileges or disadvantages in their examples that you hadn’t previously recognized or thought about before.

Activity 5.2

Privilege is easy to overlook, which is why this Buzzfeed article by Morgan Sloss is useful. It challenges you to think about privileges that you probably haven’t considered before. Review the list in the article itself as well as the user comments at the bottom. What other types of privilege can you think of that are often overlooked? Come up with as many as you can from your own life.

Marginalized Identities in Online Spaces

As noted in the introduction of this chapter, “access” can mean different things—having access to digital technologies, having access to the digital literacy skills necessary to effectively navigate online spaces, and having social access (acceptance) in various online communities. Marginalized groups lack access in at least one, if not all, of these ways. While many people are privileged enough to have automatic access to digital technologies and the personal, educational, professional, and civic advantages that come with them, others are excluded as an ongoing consequence of their oppression. This is called the digital divide, referring to the growing chasm between groups of people who have access and those who do not (IEEE.org).

Indeed, the digital divide is getting worse. For one thing, as new technologies emerge and integrate into our everyday lives, the list of technologies and applications that marginalized groups can’t access grows. For another thing, access to these technologies is increasingly a way of life for those who have it. This has been particularly true following the COVID-19 pandemic, in which everything—education, professional activities, health care access, and so on—shifted to online spaces and created a large disadvantage for people without internet access (University of Washington Bothell). Lan Fang et al. discuss those disadvantages:

Information and communication technologies (ICTs), products that enable information storage, retrieval, manipulation, transmission, or reception in digital form, can improve access to goods and services; generate and maintain a safe and secure independent living environment; facilitate self-management of age-related challenges; and enable social connectivity and participation.…The inaccessibility of ICTs has resulted in significant inequities in respect to who can access, use, and benefit from these interventions.

There are interrelated factors that contribute to the digital divide. While it might be easy to simplify the issue into “haves” and “have-nots,” the problem is more complex, centering around the different types of access. Beaunoyer et al. identify four “proximal factors” that determine a person’s ability to successfully use digital technologies:

- Technical means—access to quality digital tools, both hardware and software, as well as internet connection

- Autonomy of use—the personal time and space required to freely use the technology

- Social support networks—connection with experienced users who can help a person learn various skills

- Experience—enough time to become familiar with and to reap the benefits from digital technology

Importantly, it’s no coincidence that some people have access to digital technologies and the benefits they provide and some people don’t. Digital inequalities mirror, and thus reinforce, existing social inequalities related to race and ethnicity, which are inherently linked to socioeconomic status and educational attainment (American Psychological Association). Fang et al. call it a “pattern of privilege,” in which a person’s social location is a determinant of other intertwined factors. Race, education, and income are connected and tend to create further challenges related to health, manual labor, strict gender roles, and so on, which further decrease the chances of someone gaining access to digital technologies. Though “access” is determined by a complex matrix of factors, there are several that stand out as particularly salient predictors:

- Age. Though the gap is getting smaller as more older adults gain access to digital spaces, there is still a significant number of older adults who aren’t online. Hall et al. found that many older adults do have access to the devices themselves, but they aren’t comfortable using digital technologies. They don’t have a clear understanding of how the technologies work, and they don’t have confidence that they will be able to learn. This is particularly concerning because so much health information—access to health records and communication with providers—occurs online.

- Socioeconomic status. Perhaps the most obvious factor is the digital gap between people who have the financial means to buy the latest technologies and internet services and those who don’t (Khan Academy). Some people simply don’t make enough to afford broadband internet or the range of devices that would allow them to be fully integrated into digital spaces. However, this also means that they lack access to resources and opportunities that might improve their financial situation—online degree programs and other educational activities, professional networking, job opportunities that are posted online or that require stable internet access, financial services, and so on. In other words, the divide grows wider as people with lower incomes fall further behind, while people with money are able to leverage digital technologies to acquire more wealth.

- Education level. People with higher levels of education are more likely to consistently and effectively use digital technologies. This article by the Pew Research Organization demonstrates that people with lower levels of education and less income are less likely to use the internet for personal and professional learning activities. Instead, “the internet is more on the periphery of their learning activities” (Horrigan). This is one instance where “access” might take a couple different forms—the money to obtain digital devices as well as the literacy skills to effectively navigate online spaces. Once again, lack of access further widens the divide, as people in this group are less likely to effectively participate in school activities that would enhance their education level (American University). As the American University article explains, students without access to quality digital devices are less likely to perform well in online learning activities and are less likely to persist to higher levels of education.

- Race. As discussed above, race is closely connected with socioeconomic status and education level. Nonwhite groups, particularly people who are Black or Hispanic, are more likely to experience poverty, which further deprives them of important resources, like educational opportunities and digital technologies, and as we’ve already seen, the negative consequences are further compounded by ongoing disadvantages and missed opportunities. What’s more, when racial minorities do gain access to online spaces, they are more likely to experience discrimination that excludes them and discourages their participation. In other words, they are denied “access” to social communities. According to Tynes, online racial discrimination is a significant problem that affects a growing number of adolescents and includes things like “racial epithets and unfair treatment” based on race and ethnicity. It might also include rude or derogatory images, videos, comments, symbols, or graphic representations. Tynes also includes “cloaked sites” in the list of discriminatory practices, created to “spread misinformation about the history and culture of certain racial/ethnic groups.”

- Gender. Though there don’t seem to be any indicators that one gender has more access to digital devices or literacy skills than another, women are more likely to experience different forms of abuse online. This article by the Council of Europe names a few examples: “non-consensual image or video sharing, intimidation and threats via email or social media platforms, including rape and death threats, online sexual harassment, stalking, including with the use of tracking apps and devices, as well as impersonation, and economic harm via digital means.” The article goes on to explain that women are more likely to be the victim of cyberbullying and sexual exploitation online. What’s more, individuals in the LGBTQ+ community are also more likely to experience online discrimination, exclusion, and harassment.

- Immigration status. Immigrants are less likely to have access to digital devices or literacy skills (Cherewka). Like other examples we’ve explored, immigration status is closely linked to other predictors, such as socioeconomic status and education level. Also, immigrants in more rural areas are less likely to have broadband services.

These are just a few of the factors that influence a person’s level of access to digital spaces along with the numerous tangible and intangible benefits that access affords. As indicated in the examples, the negative effects of having little or no digital access are cumulative, including fewer educational and employment opportunities, limited social support (Courtois and Verdegem), diminished health literacy and access to health care resources (Beaunoyer et al.), and more struggles with mental health and social well-being (Büchi et al.). Beaunoyer et al. explain:

As an emerging form of social exclusion, digital exclusion contributes to worsen material and social deprivation. Being digitally excluded has consequences on health determinants such as education, work, and social networks, which impacts contribute in return to maintain limited access and use of technologies, a phenomenon referred to as the “digital vicious cycle.”

Activity 5.3

This section touched briefly on some of the more obvious consequences of the digital divide, especially for those populations that don’t have access to digital tools, literacy skills, and social communities. See if you can come up with other consequences—for individual populations as well as society as a whole. Some of the ongoing effects might be fairly obvious and significant, while others might be more subtle.

Critical Literacy in Action

Social inequality is a complex and pervasive problem, and there aren’t any simple solutions. Nevertheless, there are things we can do to help close the digital divide, especially if we make a conscious effort to pay attention to the disadvantages that other people face and practice an attitude of inclusion. For one thing, we can support programs and government policies that are working toward digital equality and oppose decisions that would increase the gap. For instance, net neutrality is a common term relating to the equal access of users and businesses to high-speed internet capabilities (Finley). It’s the principle that internet providers should not be able to discriminate against some types of content (by blocking or slowing down internet speeds) in favor of others (that load much faster), which in turn reduces the access of some people and/or businesses to have their message heard.

Ultimately, without net neutrality, providers can prioritize some information—and also some types of people—over others based on people’s ability to pay more money. According to Finley, “The fear is that, over time, companies and organizations that either can’t afford priority treatment, or simply aren’t offered access to it, will fall by the wayside.” Unfortunately, many of the net neutrality laws that had been in place during the Bush and Obama administrations were overturned in 2017, which has opened the door for providers to take advantage of fewer restrictions and more financial incentives.

You can also support government programs and projects that are geared toward closing the divide. For instance, part of Biden’s American Jobs Plan is to “revitalize America’s digital infrastructure,” which would include 100% broadband coverage so that “unserved and underserved areas” gain access to internet services, greater competition among a greater number of large and small providers, and reduced internet prices (The White House). However, as Chakravorti of the Harvard Business Review points out, “Infrastructure alone does not necessarily translate into adoption and beneficial use. Local and national institutions, affordability and access, and the digital proficiency of users, all play significant roles—and there are wide variations across the United States along each of these.” In addition to the infrastructure that makes it possible for underserved populations to access the internet, Chakravorti points out the need to increase “inclusivity” (so that broadband is affordable and increases the likelihood that people will be able to adopt internet technologies), “institutions” (to promote government policies and best practices that prioritize public access), and “digital proficiency” (to help people learn how to effectively navigate digital technologies to send and receive information).

According to the North Carolina Department of Information Technology (NCDIT), adoption is really key. Yes, it’s important to expand the infrastructure to make broadband services available and affordable, and it’s helpful to subsidize the cost of emerging technologies so that everyone can use and benefit from them, but availability doesn’t matter if people don’t adopt the technology, either because they don’t have the skills to effectively engage with it or because they don’t believe that it’s beneficial. As the NCDIT page explains, there are grants and other programs available to not only provide resources to underserved communities but also supply the training needed to help them successfully utilize those resources.

DEI Framework

While there are some political agendas and grant programs that might seem pretty far removed from your everyday sphere of influence, there are also more direct, individual practices you can adopt to create an online environment where everyone feels welcome. The whole point of understanding your own privilege in certain circumstances is to better identify moments where other people are marginalized in some way and to utilize your own influence to help rectify those issues. While the DEI framework is most often used by businesses trying to cultivate a more just and welcoming environment, it is also a great way to begin thinking about your digital practices so that you can have a positive effect on the communities you’re a part of.

DEI stands for diversity, equity, and inclusion (Extension Committee on Organization & Policy). According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), “The diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) function deals with the qualities, experiences and work styles that make individuals unique (e.g., age, race, religion, disabilities, ethnicity) as well as how organizations can leverage those qualities in support of business objectives.” In other words, being inclusive of different identities and perspectives is not only ethical but it promotes business success. In fact, a 2022 study found that companies with a diverse workforce earn 2.5 times more revenue per employee, and inclusive teams are 35% more productive (Research and Markets). Let’s look at each word in the acronym and consider how it might influence your online activities:

- Diversity. In this case, diversity refers to differences in race, gender, location, socioeconomic status, age, religion, (dis)ability—anything related to a person’s social location that has a natural influence on the way that they experience and perceive the world. People and organizations that work to foster diversity are intentional about cultivating a diverse community because they see the inherent value in having different types of people and perspectives. It enriches the overall community, as people share their own ideas and experiences and are likewise challenged to consider viewpoints that are different from their own. What this means for your online activities is that you too would be intentional about openly and respectfully engaging with diverse people to better understand their experiences and ways of thinking. It doesn’t mean you have to agree with other people all of the time, but it does mean that you should try to listen and to see where they are coming from. In addition to engaging with different people on various social media platforms, you’d also make an effort to diversify the places where you go to get your news and entertainment, all of which would make you more sensitive to the experiences and concerns of people who are different from you.

- Equity. This term refers to practices that value and prioritize social justice so that all people have equal opportunities. To be a proponent of equity means that you have a deeper understanding of the inequalities that persist in our society and the tangible effects that they have on people’s lives. You not only recognize that these inequalities exist, but you advocate for marginalized groups in an effort to challenge discriminatory practices and mindsets and evenly distribute resources and opportunities. It means that as you engage with different groups of people online, you’d be aware of overt discriminatory practices as well as microaggressions that make people feel excluded or uncomfortable. At the very least, you’d stop engaging with groups and/or individuals who exhibit these negative attitudes. You might even feel compelled to address discriminatory behaviors in order to (hopefully) develop other people’s sense of awareness and sensitivity.

- Inclusion. Whereas equity is about addressing social injustice, inclusion is about making people who are typically marginalized feel welcome, like they are wanted and valued. In fact, the word “tolerance” has in some ways developed a negative connotation because it doesn’t imply that someone is truly wanted. To feel like someone is simply tolerating you would probably not make you feel particularly welcome. You’d feel like you are a nuisance. You’d still feel marginalized. Inclusion is about going out of your way to make people feel comfortable and included in the group. You’d invite other people to share their perspectives and participate in the conversation. You’d affirm their sense of belonging and the benefit/insight that they bring to the group.

Utilizing this DEI framework won’t help with the larger problem of the digital divide, but it does help with one kind of access. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, there are different kinds of access, including not only access to the technology or the skills necessary to use that technology but also access to groups online where people feel that they are respected and that their voices are heard. If more people enacted a DEI mentality as they engaged with different groups of people in digital spaces, there would be fewer “privileged” spaces where some people feel ignored or unwelcome.

Practicing Third Persona

Admittedly, it can be difficult sometimes to step outside of your own perspective to really understand or predict how someone from a marginalized group might be feeling in response to a particular conversation or message. It’s the type of thing that requires intentionality and practice. It also requires a degree of humility because the odds are that as you engage with different types of people, you might unintentionally say something that is offensive or insensitive, and in those moments, the best thing to do is to apologize and learn from the situation by trying to understand it from the other person’s point of view.

Learning also comes from thinking critically about the messages that you encounter as well as the messages that you create in order to identify the effect that they might have on your audience. Here we’re dipping into the rhetorical literacy that is covered more extensively in part two of the textbook, but it’s worth a brief mention here, since thinking critically about your messaging also requires thinking critically about your audience and your underlying purpose. The main concept that is really helpful for identifying insensitive or exclusive messages is called “third persona,” a concept that was introduced by Philip Wander in 1984. However, first it might be helpful to refresh your memory about “point of view.” You’ve probably learned that a text can be written in first person (with the focus on the speaker—“I” or “me”), second person (with the focus on the audience—“you”), or in third person (with the focus on other people outside of the group—“he,” “she,” “they”).

Wander’s concept of third persona was a response to Edwin Black’s 1970 essay, “The Second Persona.” In his essay, Black discusses the concept of second persona as the audience that is implied within a message. It isn’t so much about the actual, real-life people who are part of the audience; it’s more about the ideal audience that is invoked in a message, which in turn invites the real audience to adopt a certain identity. Walter Ong discusses a similar concept in his article “The Writer’s Audience Is Always a Fiction,” in which the writer imagines an ideal audience and crafts their message accordingly. For example, if a student is going to miss class for a doctor’s appointment, they might send a professor an email that looks like this:

Professor X, I’m so sorry to have to miss class, but I have a doctor’s appointment tomorrow that I wasn’t able to reschedule. I know that you take attendance very seriously, as do I, but I’m having some important tests run tomorrow. I’ll be sure to get notes from a friend so I can catch up on what I miss. Thank you for understanding!

In this short email, the student invites the professor to adopt a certain identity as someone who “takes attendance very seriously” but would also be understanding of the importance of a doctor’s appointment and the tests that are scheduled. The student is also portraying the professor and the class as a serious endeavor, implied by the fact that she is “sorry” to miss and that she knows important information will be presented, so she’ll be sure to find out what she missed from a friend. The actual professor—the one behind the computer screen reading the email—may or may not have all of those qualities, but chances are that the professor would read the email and feel somewhat compelled to adopt the identity of a serious yet gracious instructor and respond positively to the student’s message. In other words, second persona is about understanding the ideal target audience and how that audience is portrayed in a particular message. A well-crafted message will invoke an audience with particular interests, qualities, and values that are appealing and therefore increase the likelihood of a positive response.

Whereas second persona is about the ideal target audience (“you”), Wander’s concept of third persona is about the segment of the audience that is left out—the “other.” He describes it as the part of the audience that is “negated” or “alienated” by a text. He says, “But just as the discourse may be understood to affirm certain characteristics, it may also be understood to imply other characteristics, roles, actions, or ways of seeing things to be avoided. What is negated through the Second Persona forms the silhouette of a Third Persona” (Wander 209). In other words, just as a message will automatically invoke ideal, good qualities that the audience should possess, it also inherently implies negative qualities that should be avoided. He makes it clear that many texts don’t do this intentionally; they simply take for granted what is “good” or “normal,” probably based on the speaker’s own social location and perspectives. Those identities are put in the center of the message, while audiences who don’t fit that criteria are pushed to the fringes. Their lived experiences and perspectives are portrayed in a negative way or ignored altogether. And often the identities that are negated in a text are those same marginalized groups that have historically been “left out” of all types of conversations, resulting in continuing inequalities: “Beyond its verbal formulation, the Third Persona draws in historical reality, so stark in the twentieth century, of peoples categorized according to race, religion, age, gender, sexual preference, and nationality, and acted upon in ways consistent with their status as non-subjects” (Wander 216).

Another example might be helpful to really see how the concept of third persona might be applied to a message. Here is an example of a simple assignment prompt for a college-level writing course:

For this assignment, you will write a rhetorical analysis of an online space—ideally someplace where you are fairly active. To begin, you should explore why you are drawn to this site. Does it in some way confirm your own Christian values? American values? You should also consider what you think is the purpose of the site and how the different elements of the site work together to help fulfill that purpose. When you get home this evening, post a brief response on our Canvas forum (around 500 words) discussing your perspective of the website you have chosen.

At first glance, this assignment prompt might seem innocent enough. It’s asking students to do a very common writing assignment—a rhetorical analysis—and to consider their own perspectives of a particular online space. However, a closer look through the lenses of second and third persona reveals a pretty significant problem when it comes to the way that the ideal audience—those conscientious students in the course—are portrayed. It assumes (second persona) several things about the audience:

- That they are “active” online.

- That they might naturally have “Christian” or “American” values as part of their identity.

- That they automatically have the extra time and the resources when they get home that evening to write a response.

- That they are confident writers and 500 words is a “brief response” that should be fairly easy.

This is the ideal, “normal” audience that is implied in the assignment prompt. Certainly, in many college classes, there are students who would fit this persona and they would likely feel compelled to step into the identity of a confident and thoughtful writer. However, many students don’t. The assignment prompt wasn’t written with the intent to make anyone feel discouraged, frustrated, or alienated, but that would absolutely be the result for some groups of students. The assignment prompt ignores the fact that some students might not be “active” online for whatever reason. It ignores the fact that students might have different nationalities or religious beliefs. It ignores the fact that many students work in the evenings or have other personal obligations that would prevent them from being able to complete this type of assignment so quickly. It ignores the reality that some students don’t have access to digital technologies or Wi-Fi at home and that for them, completing this assignment would be much more difficult. It also ignores students who struggle to write, who would need a lot more time and direction to put together a 500-word response.

Because of the power dynamics and the nature of some of these assumptions about what it means to be a “normal” college student, chances are that students who did feel alienated by this message wouldn’t necessarily challenge the professor or even call to attention the difference in their own identities and experiences. Some would probably still do the assignment, but they would have to work a lot harder to find a public-access computer and to spend the couple of hours it might take to complete the assignment. Some might go ahead and write an analysis that centers their own values regarding religion, ethnicity, race, sexuality, and so on, or they might feel pressured to conform to “American” or “Christian” or some other dominant identity because they think they will get a better grade or because they don’t want to draw attention to themselves as different. And then there will be some students who are alienated by this assignment prompt and won’t do it because they don’t have the technological resources or the assumed writing abilities to complete it in one evening. They’ll get a zero for the assignment, and if the course is sprinkled with lots of similar assignments that put them at a disadvantage, they’ll eventually disengage and either withdraw or fail the course.

This might seem like an extreme example, but the reality is that messages have a great deal of influence over an audience and their responses. For audiences who feel included in and valued by the message, who feel capable of stepping into the ideal persona that is portrayed, they are likely to respond positively to the message and receive the ongoing rewards of acceptance and prosperity, be they social, financial, educational, and so on. The reverse is true for people who aren’t included in the message, who don’t feel valued or capable of stepping into the ideal persona, who feel ignored altogether.

As we have studied throughout this chapter, there are tangible disadvantages that come with being excluded from digital spaces. Taking a critical approach to your own digital writing and the messages that you encounter online is an important step toward true equality where everyone has access. Obviously, the point of adopting a DEI framework and analyzing a message—particularly your own—through the lens of third persona is to make necessary revisions to your habits of mind and digital practices that might unintentionally perpetuate others’ marginalized status. In an ideal world, there wouldn’t be “privileged” spaces; there would instead be a rich, diverse community of ideas and perspectives that benefit everyone involved and continually invite more people to the conversation(s). Critical literacy is at the very heart of making that vision a reality.

Activity 5.4

Reread the section of this chapter about DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion). For each concept of this acronym, write a reflection about your own digital practices. What are you already doing in this area? What problems or challenges do you encounter? In which spaces do you feel “included”? In which spaces do you feel “excluded” in some way? What types of things can you do in each category to have a more positive effect?

Activity 5.5

Select a handful of texts in which you are in the audience. This might be a diverse selection of text messages / emails directly to you or a group that you’re a part of, and it might also include messaging on social media or websites in which the audience is broader. Analyze these messages using second and third persona. Remember that second persona is about the ideal target audience, and third persona is about members of the target audience who are ignored or devalued. What types of qualities (and identities) are implied as positive or normal in the message you selected? What types of identities are overlooked or even devalued?

Now do the same thing for a handful of texts that you have recently written. Once again, try to select a variety of texts and emails as well as other messages, such as blog posts, social media posts, forum responses, and so on. What do you notice about the assumptions that you make about your audience? What kinds of qualities do you assume that your audience has? What types of people might feel marginalized when they read your message? Are there ways that the text could have been written differently to be more inclusive?

Discussion Questions

- What are the different definitions of the word “critical”? How can they be applied to your own digital writing?

- What are the different types of “access” that are referred to in the chapter? Can you give a deeper explanation or example for each one?

- What is privilege? What forms of privilege do you have that put you at an advantage over others? What forms of privilege don’t you have?

- The chapter also makes some additional distinctions about the concept of privilege. What are they? Which ones strike you as particularly relevant or important for you and the experiences you’ve had?

- What is the “coded gaze”? The chapter identified one example of a biased algorithm. Can you think of other examples? What are the ethical consequences of these technologies?

- What is the digital divide? In what ways is the digital divide getting worse? What are the four different factors that influence a person’s ability to participate in the digital realm? Can you think of other factors that might be important or relevant?

- How is the digital divide connected with other forms of privilege? In other words, people who are denied “access” in some way also experience discrimination and inequalities based on other factors (e.g., race, age, ability, gender). Explain this connection.

- What are some of the more prominent factors that influence a person’s level of digital access?

- How are the advantages and disadvantages of digital access “exponential”? What does this mean? Can you come up with some examples?

- What is the DEI framework? What do the different terms in the acronym stand for? How can this be applied to help remedy inequalities of access? Why do you think that businesses that utilize DEI are more successful?

- Explain the concepts of second and third persona. How can these concepts be used as a lens to critically analyze a text to understand how “access” is being denied to certain identities?

Sources

American Psychological Association. “Ethnic and Racial Minorities & Socioeconomic Status.” APA.org, July 2017, https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/minorities#:~:text=The%20relationship%20between%20SES%2C%20race,SES%2C%20race%2C%20and%20ethnicity.

American University. “Understanding the Digital Divide in Education.” American.edu, 15 Dec. 2020, https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/digital-divide-in-education#:~:text=Students%20from%20marginalized%20communities%20are,is%20for%20more%20privileged%20students.

Beaunoyer, Elisabeth, et al. “COVID-19 and Digital Inequalities: Reciprocal Impacts and Mitigation Strategies.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 111, Oct. 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7213963/.

Black, Edwin. “The Second Persona.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 56m, no. 2, 1970, 109–119, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00335637009382992?journalCode=rqjs20.

Boyers, Robert. “The Term ‘Privilege’ Has Been Weaponized. It’s Time to Retire It.” The Guardian, 8 Nov. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/nov/08/the-term-privilege-has-been-weaponized-its-time-to-retire-it.

Büchi, Moritz, et al. “How Social Well-Being is Affected by Digital Inequalities.” International Journal of Education, vol. 12, 2018, 3686–3706,https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3871751.

Buolamwini, Joy. “Fighting the ‘Coded Gaze.’” Ford Foundation, 26 June 2018, https://www.fordfoundation.org/news-and-stories/stories/fighting-the-coded-gaze/#:~:text=I%20think%20of%20the%20coded,a%20narrow%20group%20of%20people.

Chakravorti, Bhaskar. “How to Close the Digital Divide in the U.S.” Harvard Business Review, 20 July 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/07/how-to-close-the-digital-divide-in-the-u-s.

Cherewka, Alexis. “The Digital Divide Hits U.S. Immigrant Households Disproportionately During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Migration Policy Institute, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/digital-divide-hits-us-immigrant-households-during-covid-19.

Council of Europe. “No Space for Violence against Women and Girls in the Digital World.” COE.Int, 15 Mar. 2022, https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/no-space-for-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-the-digital-world.

Courtois, Cédric, and Peter Verdegem. “With a Little Help from My Friends: An Analysis of the Role of Social Support in Digital Inequalities.” New Media & Society, vol. 18, no. 8, 9 July 2016, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814562162

Eubanks, Virginia. Automating Inequality. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2017.

Extension Committee on Organization & Policy. “What is Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)?” DEI.Extension.org, n.d., https://dei.extension.org/.

Finley, Klint. “The WIRED Guide to Net Neutrality.” Wired.com, 5 May 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/guide-net-neutrality/.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking. “Defining Critical Thinking.” CriticalThinking.org, 2019, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766.

Fox, Pamela. “The Socioeconomic Digital Divide.” Khan Academy, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/computing/computers-and-internet/xcae6f4a7ff015e7d:the-internet/xcae6f4a7ff015e7d:the-digital-divide/a/the-socioeconomic-digitaldivide.

Hall, Amanda, K., et al. “The Digital Health Divide: Evaluating Online Health Information Access and Use Among Older Adults.” Health Education & Behavior, vol. 42, no. 2, 25 Aug. 2014, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1090198114547815?journalCode=hebc.

Helsper, Ellen A., and Alexander J. A. Deursen. “Do the Rich Get Digitally Richer?” Quantity and Quality of Support for Digital Engagement. Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 5, 2017, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1203454.

Horrigan, John B. “Lifelong Learning and Technology.” Pew Research Center, 22 Mar. 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/03/22/lifelong-learning-and-technology/#:~:text=The%20survey%20clearly%20shows%20that,take%20advantage%20of%20the%20internet.

Human Rights Watch. “Years Don’t Wait for Them: Increased Inequalities in Children’s Right to Education Due to Covid-19 Pandemic.” HRW.org, 17 May 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/05/17/years-dont-wait-them/increased-inequalities-childrens-right-education-due-covid.

IEEE.org. “Solutions to the Digital Divide: Moving Toward a More Equitable Future.” IEEE.org, 2023, https://ctu.ieee.org/solutions-to-the-digital-divide-moving-toward-a-more-equitable-future/#:~:text=The%20digital%20divide%20refers%20to,have%20access%20to%20the%20internet.

Johnson, Allan. Privilege, Power, and Difference. Boston, McGraw Hill, 2005.

Khan Academy. “The Socioeconomic Digital Divide.” Khan Academy, n.d., https://www.khanacademy.org/computing/computers-and-internet/xcae6f4a7ff015e7d:the-internet/xcae6f4a7ff015e7d:the-digital-divide/a/the-socioeconomic-digitaldivide.

Lan Fang, Mei, et al. “Exploring Privilege in the Digital Divide: Implications for Theory, Policy, and Practice.” Gerontologist, vol. 59, no. 1, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny037.

Li, Cheng. “Worsening Global Divide as the US and China Continue Zero-Sum Competitions.” Brookings, 11 Oct. 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/10/11/worsening-global-digital-divide-as-the-us-and-china-continue-zero-sum-competitions/.

McCrann, John. T. “The Reparations I Owe: An Exponential Growth Model of Privilege.” EdWeek.org, 13 July 2016, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-the-reparations-i-owe-an-exponential-growth-model-of-privilege/2016/07.

Metz, Cade. “Who Is Making Sure the A.I. Machines Aren’t Racist?” The New York Times, 23 June 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/technology/artificial-intelligence-google-bias.html#:~:text=Buolamwini%20and%20Ms.,31%20percent%20of%20the%20time.

Nguyen, Sarah Hoan, et al. “How Do We Make the Virtual World a Better Place? Social Discrimination in Online Gaming, Sense of Community, and Well-Being.” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 66, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101747.

North Carolina Department of Information Technology. “Closing the Digital Divide.” NCBroadband.gov, n.d., https://www.ncbroadband.gov/digital-divide/closing-digital-divide.

Research and Markets. “Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) Global Market Report 2022.…” Research and Markets, 9 Aug. 2022, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/08/09/2494604/0/en/Diversity-and-Inclusion-D-I-Global-Market-Report-2022-Diverse-Companies-Earn-2-5-Times-Higher-Cash-Flow-Per-Employee-and-Inclusive-Teams-Are-More-Productive-by-Over-35.html.

Scripps College. “Social Identity Wheel.” ScrippsCollege.edu, n.d., http://www.scrippscollege.edu/laspa/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/Social-Identity-Wheel.pdf.

Sloss, Morgan. “People Are Pointing Out Privileges That Lots of People Don’t Even Recognize, And This is So Important.” Buzzfeed.com, 25 July 2021, https://www.buzzfeed.com/morgansloss1/things-people-dont-realize-are-privileges-reddit. 15 Oct. 2022.

Society for Human Resources Management. “Introduction to the Human Resources Disciplines of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” SHRM, n.d., https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/toolkits/pages/introdiversity.aspx.

Sridhar, Rama. “Bridging the Digital Divide is Key to Building Financial Inclusion.” Forbes, 10 Sept. 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinessdevelopmentcouncil/2021/09/10/bridging-the-digital-divide-is-key-to-building-financial-inclusion/?sh=2c4c395b75ae.

Townsend, Phela. “Disconnected: How the Digital Divide Harms Workers and What We Can Do about It.” The Century Foundation, 22 Oct. 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/disconnected-digital-divide-harms-workers-can/?session=1.

University Libraries at Rider University. “Privilege and Intersectionality.” Rider University, 9 Oct. 2022, https://guides.rider.edu/privilege.

University of Washington Bothell. “The Pandemic Reveals Digital Divide.” UWB.edu, 1 July 2021, https://www.uwb.edu/news/july-2021/pandemic-reveals-digital-divide.

Tynes, Brendesha, M. “Online Racial Discrimination: A Growing Problem for Adolescents.” APA.org, Dec. 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20200724033710/https://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2015/12/online-racial-discrimination.

Wander, Philip. “The Third Persona: An Ideological Turn in Rhetorical Theory.” Central States Speech Journal, vol. 35, no. 4, 1984, 197–216, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10510978409368190.

The White House. “Fact Sheet: The American Jobs Plan.” WhiteHouse.gov, 31 Mar. 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/31/fact-sheet-the-american-jobs-plan/.