7 The Everyday Function of Rhetoric

Remember that word “ubiquitous” from the introduction? It’s probably a fairly obvious thing to say that digital technology is everywhere, embedded in our most basic daily tasks and often going completely unnoticed. However, following our discussions in the first section of the textbook, the hope is that you have a deeper understanding of the ubiquitous nature of digital media. Now we turn our attention from critical literacy to “rhetorical literacy.” Even more pervasive than our use of digital technology is our use of rhetoric, and much like the technologies we use, rhetoric often goes unnoticed. In fact, you are constantly sending messages out into the world—whether it be written or verbal messages that you carefully crafted beforehand or unanticipated conversations, offhand remarks, facial expressions, or body language. Even the clothing you wear sends messages to people about who you are and what your interests, occupations, and moods might be.

Unfortunately, rhetoric is a word that is often misunderstood. People sometimes think of it as an act of manipulation—something politicians use to garner attention and increase votes, but their words don’t have any real meaning. It’s all “hot air.” However, while this is certainly an example of rhetoric, it’s nowhere near complete. In simple terms rhetoric is the art of communication. If you were to Google the term, the Oxford Languages would tell you that rhetoric is “the art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the use of figures of speech and compositional techniques.” The second definition given is “language designed to have a persuasive or effective effect on its audience, but often regarded as lacking in sincerity or meaningful content.” That’s the “hot air” definition described earlier. However, these definitions are both inadequate because they fail to recognize the more subtle, everyday uses of rhetoric. While you might intentionally use rhetoric for specific occasions—a speech or a debate or an op-ed article, for instance—you also use rhetoric in the more mundane interactions you have with people all day long. You use rhetoric as you walk down the aisle at the grocery store, drive through town, or sit quietly in a classroom. You might not always be aware of the messages you are sending and the effect that you have on other people, but you are indeed using rhetoric, and the more that you are able to cultivate an awareness of rhetoric and how it functions in your everyday life, the more effective you will be in your interactions with other people—both in person and online.

The goal of this chapter is to help you understand what rhetoric is and how foundational it is to our everyday lives. Far from being an act of manipulation, rhetoric in its most useful form is about enhancing mutual understanding and respect in order to facilitate compromise, problem-solving, and healthy relationships. It’s also inherently connected to your sense of identity and the way that you develop knowledge about the world. Defining rhetoric as the art of effective communication intentionally broadens the parameters of when and how we use rhetoric. It’s also fairly simple, particularly compared to the definitions that other rhetoricians have given throughout history. For instance, American Rhetoric lists a number of “scholarly” definitions of rhetoric:

- “The art of enchanting the soul” (Plato).

- “The faculty of discovering in any particular case all of the means of persuasion” (Aristotle).

- “One great art comprised of five lesser arts: inventio, dispositio, elocutio, memoria, and pronunciatio” (Cicero).

- “That art or talent by which discourse is adapted to its end. The four ends of discourse are to enlighten the understanding, please the imagination, move the passion, and influence the will” (George Campbell).

- “The study of misunderstandings and their remedies” (I. A. Richards).

- “A form of reasoning about probabilities, based on assumptions people share as members of a community” (Erika Lindemann).

The list goes on, but the point is that there are a lot of different ways that we could consider rhetoric and its function. What all of these definitions have in common is a focus on purpose—what the communicator is trying to achieve as a result of their message, whether written or spoken, whether explicit or implicit. Similar to our definition of rhetoric is the one articulated by Andrea Lunsford, who defines rhetoric as “art, practice, and study of human communication” (American Rhetoric). This is also a broad definition that encompasses not only the message itself but also the academic and personal endeavor of understanding how communication works and how it can be utilized effectively.

Perhaps one more definition will be useful as we launch into this unit about rhetorical literacy and its relationship to digital communication. The Department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at San Diego State University defines rhetoric like this:

Rhetoric refers to the study and uses of written, spoken and visual language. It investigates how language is used to organize and maintain social groups, construct meanings and identities, coordinate behavior, mediate power, produce change, and create knowledge. Rhetoricians often assume that language is constitutive (we shape and are shaped by language), dialogic (it exists in the shared territory between self and other), closely connected to thought (mental activity as “inner speech”) and integrated with social, cultural and economic practices. Rhetorical study and written literacy are understood to be essential to civic, professional and academic life.

That’s obviously a more complex and nuanced definition than some of the others we’ve reviewed, but it accurately captures the significance of rhetoric to our thought processes, our civic engagement, our relationships, our activities, and our very identities. In this first chapter of the rhetorical literacy unit, we’ll take a closer look at the elements that comprise the rhetorical situation as well as examples of rhetorical appeals that are used to enhance the effectiveness of a message. Developing a deeper awareness of these concepts will help you identify how they are used in the messages you encounter and utilize them more intentionally and effectively in the messages you send.

Learning Objectives

- Gain a broad understanding of what rhetoric is and how pervasive it is in your everyday life.

- Understand what the rhetorical situation is and the key elements that are involved.

- Consider the criteria of rhetorical discourse in contrast to other forms of speech.

- Learn how the elements of a rhetorical situation can be transferred from one circumstance to the next for a deeper analysis of effective communication.

- Examine the three main types of rhetorical appeals and how they can be applied.

- Learn more specific rhetorical strategies of rhetorical modes and rhetorical devices and how they can be used to enhance a message.

- Consider the larger functions of rhetoric in everyday conversations.

The Rhetorical Situation: Key Terms

Probably the best way to cultivate a deeper understanding of rhetoric is to consider the elements of the rhetorical situation, which was defined by Lloyd Bitzer in his 1968 essay “The Rhetorical Situation.” In this essay, he considers the elements that are present when rhetorical discourse emerges—the circumstances that precipitate the message and would have an impact on how it is received. No message can be fully understood without considering the larger context, which Bitzer says is crucial in understanding the effectiveness of that message to meet its intended goal. Bitzer defines rhetoric as

a mode of altering reality, not by the direct application of energy to objects, but by the creation of discourse which changes reality through the mediation of thought and action. The rhetor alters reality by bringing into existence a discourse of such character that the audience, in thought and action, is so engaged that it becomes mediator of change. In this sense, rhetoric is always persuasive. (4)

In other words, rhetoric creates action. It has the power to influence the thoughts and behaviors of the audience in certain ways, depending on the motives of the speaker along with the message itself and the context in which that message is delivered—all elements of the rhetorical situation.

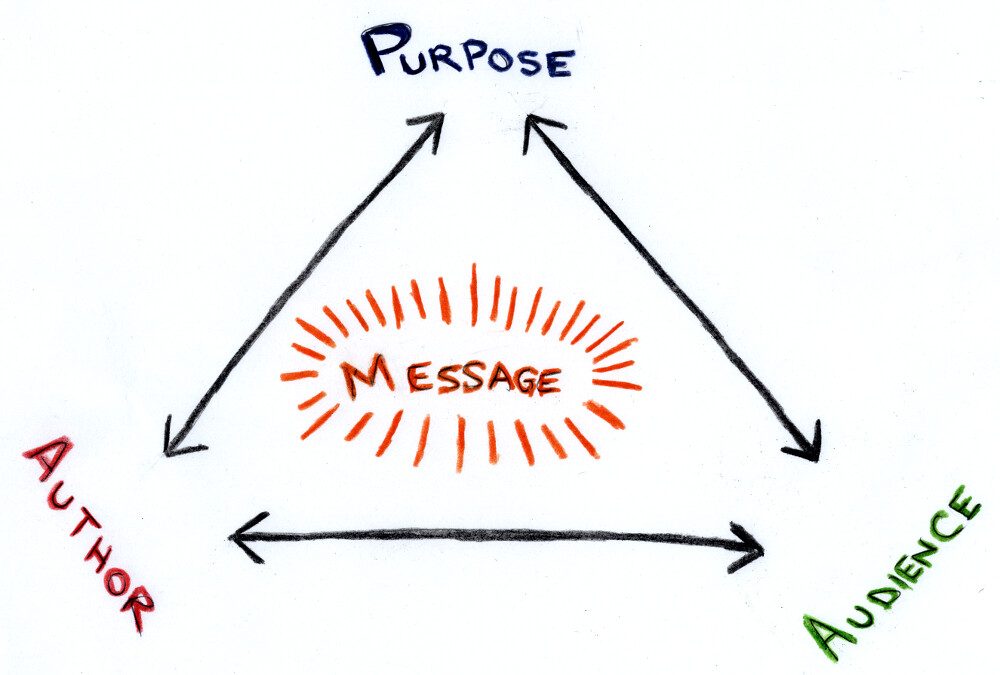

Let’s back up, though, and consider the most fundamental element of rhetoric: purpose. All rhetorical discourse has a purpose, something that the speaker hopes to accomplish as a result of the message. As already discussed, this purpose might be really obvious and explicit. For instance, you might find yourself in some sort of debate about a political issue, and so you are using logical reasoning and evidence to convince your audience to agree with your position. Or you might be out with friends or family members, and you want to convince them to eat at a certain restaurant or agree to see a specific movie with you. Once again, you’d use all of your rhetorical skills to get them to do whatever it is you are suggesting. In many other circumstances, though, the purpose might not be quite so obvious. Maybe you’re out for a walk in your neighborhood and when you pass one of your neighbors, you feel compelled to stop and say hello. Maybe your neighbor is the talkative sort, and so you end up locked in a conversation for longer than you might like, but you don’t want to be rude. That is also a rhetorical situation with a purpose: to maintain a friendly relationship with your neighbor. And if someone stops you and asks you for directions, your response would also be rhetorical. Your purpose would be to give clear directions so they can get where they want to go.

Every time you craft a message for an audience—whether it’s an in-person conversation, an email, a text message, a “like” on Facebook, or a quick wave hello to a friend in the hallway at school—you have a purpose. It might be to persuade your audience about a particular issue or course of action, it might be to inform them about a process or a concept, or it might be to give a positive impression of yourself and cultivate or maintain social relationships. Rhetoric, then, refers to the communication strategies you use in a given situation to meet that purpose, to influence the attitudes and behaviors of your audience. This suggests, as Bitzer says, that all rhetoric is persuasive. Even if your primary purpose is to inform your audience about a topic, there is an underlying purpose to convince them that the topic is worthwhile and that you are a credible source of information. There is also the reality that one seemingly minor message could have more than one purpose, often with a social component. A teacher who gives a short lesson in class has multiple purposes—to inform students clearly about the topic, to persuade them that this is an important topic worth their time and effort, to encourage them that they are able to learn and effectively apply the material, to maintain a positive social rapport with the class so that students are engaged and more open to learning. It might be a five-minute lesson about semicolons, but the underlying rhetorical purpose is likely multifaceted and nuanced.

One important aspect of Bitzer’s essay about the rhetorical situation is his discussion of exigence. According to Bitzer, before a speaker has a purpose, there must be an exigence, which he defines as “an imperfection marked by urgency” (6). Or, as Kate Mele puts it, exigence is the source, the “driving force.” Just like a river starts from somewhere—a spring—Mele explains that a message also starts from somewhere: the exigence. To really understand a rhetorical message and the speaker’s purpose, it’s crucial to understand the exigence that prompted the message. If, for example, you wake up sick one morning and can’t make it into work, that’s an exigence that prompts a message to your boss. Most people can’t simply not show up to work. You’d have to notify a boss or coworkers in some way to avoid confusion and any potential problems that could arise from your absence. These are the imperfections—the exigence—that would compel you to send a text message to coworkers or to call in sick to your boss.

An exigence might be a problem that has already arisen that needs to be addressed. For instance, if you fail to call in sick and you receive angry text messages from your coworkers, that’s a problem that has materialized and has to be addressed. Alternatively, an exigence might be a potential problem that could arise if you don’t speak up. For instance, you’d call in sick to prevent the potential confusion and chaos that might arise from your absence. Similarly, you engage in the conversation with your neighbor, even though you don’t want to, to avoid the negative consequence of making your neighbor mad or hurting their feelings. Exigence is so important because it compels the message, it informs the speaker’s purpose, and the effectiveness of the message can be evaluated based on whether the exigence is resolved. In fact, according to Bitzer, rhetoric is about understanding the underlying problem and then creating discourse that can fully or partially resolve that problem. So in our example of you calling in sick to work, the exigence isn’t the fact that you are sick. Calling in to your boss won’t have any effect on whether or not you are sick. The exigence is the negative consequences that could arise at work that day—either in the overall workflow or in the impression that your boss and coworkers have of you. Communicating clearly with everyone about your situation would help resolve those potential problems.

Like many other aspects of rhetoric, the idea of exigence can be fairly complex when you consider various elements of the rhetorical situation and the different perspectives involved. For one thing, there might be multiple exigencies that inform a single message. If we go back to our example above about calling in sick, one exigence would certainly relate to the more productive aspects of the workplace. Being short-staffed would mean that important tasks aren’t completed or they aren’t completed well. It could have an impact on production quality, customer satisfaction, sales revenue, and so on. Another exigence to the same message might be social. If you don’t let others know you won’t be at work, they will think of you as being lazy and inconsiderate. Those relationships might be strained the next time you see those people if you don’t let them know what’s going on. Another exigence might relate to your own professional success. If you don’t call in, you might get fired, or you might not be seriously considered for the next raise or promotion.

Not only do multiple exigencies exist, but the very existence of an exigence is up to the interpretation of the rhetor. Whereas Lloyd Bitzer argued that the rhetorical situation compels rhetorical discourse, Richard Vatz argued that there isn’t a single, objective rhetorical situation that exists outside of our individual interpretations. It’s up to each individual to select the details from a particular situation that are important and then to interpret the meaning and the potential consequences of those details. Vatz says, “I would not say ‘rhetoric is situational,’ but situations are rhetorical; not ‘…exigence strongly invites utterance,’ but utterance strongly invites exigence; not ‘the situation controls the rhetorical response…’ but the rhetoric controls the situational response” (159). In other words, we wouldn’t all objectively agree that an exigence exists or that one specific response is the “right” one. Individual interpretations, values, and agendas inform how we perceive a situation and how we respond.

Once we understand the underlying exigence, which compels the purpose of the rhetorical discourse, we’d consider the other elements of the rhetorical situation to evaluate the effectiveness of the message:

- The speaker—the person who is sending the message. We’d probably look more closely at this person’s authority on the subject, their reputation for being trustworthy, and the relationship they have with the audience. If you are someone who calls in sick all the time, for instance, then chances are your message won’t be as well received by your boss because you have already created a negative impression.

- The audience—the intended recipients of the message. Per our definition above, the audience has the power to resolve the exigence in a rhetorical situation by adopting certain attitudes and behaviors. In that case, a closer look at the audience—their current attitudes, values, experiences, expectations, impressions of the speaker, and so on—is crucial in understanding the effectiveness of a message. If you did wake up sick and needed to let people know, your message would be very different if you were sending it to your boss as opposed to your family or friends. Your relationship with those potential audiences and their expectations are vastly different.

- The message—the spoken, written, or visual text that corresponds with the speaker’s purpose. This is the mediating tool intended to help the target audience understand the speaker’s thoughts and ideas and to compel them to respond in ways that will resolve the exigence.

- Kairos—the most opportune timing of a message (Pantelides). Again, this is a highly contextual element that considers the message itself as well as the location, the expectations of the audience, and other constraining factors. For instance, if you are interested in asking someone out on a date, you’d consider the appropriate moment for this type of conversation that would increase your chances of success. You’d wait until they are in a good mood and not distracted by other conversations or tasks. You might also wait until you are with that person in a place that is fairly quiet. All of those elements relate to kairos, which would have a significant influence on the audience’s response.

- Constraints—the “persons, events, objects, and relations which are parts of the situation because they have the power to constrain decision and action needed to modify the exigence” (Bitzer 8). Anything that could interfere with the audience’s willingness to react positively to the message—whether their own beliefs and attitudes, their negative impression of the speaker, past experiences, a lack of understanding about key concepts or cultural values—is considered a constraint. Though not all constraints can be overcome, the key to a successful message is often the speaker’s ability to predict and craft their message to overcome as many constraints as possible.

These are but a few of the elements that are present in any rhetorical situation. Other considerations might include the medium that the speaker uses to communicate the message (be it with spoken language, sign language and gestures, an email, etc.), the genre of the message (with standard conventions that might dictate things like format, organization, and tone of the message), and the larger historical and social context that influences the way that an audience would interpret a message. What is important to keep in mind is that while all of the specific details of a rhetorical situation are unique, the elements themselves are always present. There will always be a speaker, a message, an exigence, a purpose, and so on, and your ability to identify and carefully consider these elements will equip you to more effectively craft a message that anticipates potential constraints and persuades your intended audience.

Activity 7.1

Summarize a handful of conversations you’ve had today—with friends, coworkers, teachers, acquaintances. They might be in person, or they might be text messages, emails, phone calls, and so on. Describe what the conversation was about and then see if you can identify some of the elements of the rhetorical situation: speaker, audience, message, purpose, exigence, kairos, and constraints.

Pay close attention to your own purpose in these conversations as well as the exigence that provoked your response and any constraints that might have existed to prevent you from meeting your goal. What does a closer examination of these conversations say about rhetoric and how it functions in your everyday life?

Rhetorical Strategies

We’ve been talking pretty broadly about the message that emerges as a response to some sort of exigence, but the message itself is the most important aspect of rhetoric. It’s the force that allows for the expression of ideas and a deeper connection with other people. It compels attitudes and behaviors that provide tangible solutions to real problems. Often the study of rhetoric requires a deeper examination of the message that is produced and how it is fitting (or not) for a given audience in a particular situation. In that case, we’d look at the rhetorical strategies of the message—the way that the message is crafted in order to help the speaker inform and/or persuade the audience.

There are many different types of strategies that we could look at. In this section, we’ll look at three primary groupings that can be particularly helpful when you are evaluating the effectiveness of a message, including your own. The first set of strategies are called rhetorical appeals, which were introduced by Aristotle in 350 BC in his classic work Rhetoric I & II (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). In it, he set forth three broad types of persuasive appeals:

- Logos refers to logic. We might try to persuade someone based on logical reasoning, principles of cause and effect, statistics, and other forms of evidence. A sound argument is one that clearly lays out the reasons for the argument and clearly articulates that line of reasoning with strong evidence. It makes explicit connections between the evidence, the reasoning, and the larger claim. It might also examine counterarguments and use the same type of evidence and logical reasoning to refute opposing views. Particularly in academic writing, logos is considered the strongest appeal because it demonstrates a high level of critical thinking and it comes to a conclusion based on an examination of the issue itself. Digital writers also use logos when they use hyperlinks to show supporting evidence, explain how a particular process or concept works, give examples, and provide statistical evidence, often in the form of pie charts or bar graphs.

- Pathos refers to emotion. This type of appeal tries to persuade readers to adopt a specific attitude or take action in some way based on an emotional response that is invoked in the message. Advertisements are often based around pathos appeals, with pictures of people who are having fun or benefiting in some way from a particular product or service, thus creating feelings of desire in the target audience, who want to experience those same benefits. Other messages might try to invoke feelings of anger or pity or fear to incite specific behaviors in the audience. An ad seeking donations for the Humane Society would likely show pictures of cute puppies and kittens. Political ads often use misleading statistics and outright fabrications to get audiences to feel angry about the opposing candidate. While pathos appeals are sometimes used to manipulate or distract audiences, there are positive uses of pathos, too, that help audiences get a deeper sense of understanding and empathy for people and problems outside of their personal experience. Narratives and descriptions are often used as pathos appeals that help audiences emotionally connect to a message. Digital writers use pathos not only in their language but also with pictures, videos, and even color choices that reinforce certain emotions.

- Ethos refers to credibility. This has everything to do with the speaker and how much the target audience trusts this person to provide accurate and reliable information on the topic at hand. The ethos appeal is often threefold. (1) Phronesis: The wisdom, experience, and credentials of the speaker. Do they have personal and/or expert knowledge about the topic? Is this person an expert in a particular field and/or has done extensive research on this topic. (2) Arête: The personal virtues, ethics, and character of the speaker. Is this an honest and ethical person? (3) Eunoia: Goodwill exhibited toward the audience. Does the speaker seem to have the audience’s best interest in mind? An audience is more likely to believe and respond positively to a person whom they trust based on that person’s past behaviors, their reputation, and perhaps their position as an established leader. While a message can’t always overcome an audience’s negative impression of the speaker, there are definite ways to build credibility by demonstrating sound evidence and research (expertise) and by crafting a message in a way that comes across as genuine and transparent (ethics). Digital writers might also develop ethos by displaying specific certifications or awards, customer testimonials, and pictures that demonstrate professional excellence or personal ethics.

While some people think of these rhetorical appeals as being antiquated—perhaps since they are Greek words that date back to Aristotle—their importance really can’t be overstated. Nearly all rhetorical discourse fits into at least one of these categories, though they aren’t mutually exclusive. (A logos appeal might also be an ethos appeal. Using evidence from a recent study, for instance, provides logical support for an argument while also building your credibility as a knowledgeable researcher.) And since all rhetoric revolves around specific purposes that solve existing or potential problems, these rhetorical appeals are the building blocks of discourse that have real consequences in the world. In fact, as we progress through the remainder of the textbook, we’ll often refer back to these appeals as guiding principles for effective digital writing.

The next group of rhetorical strategies that we’ll examine are the modes of discourse, which are more specific categories that fit under the larger umbrella of the logos, pathos, and ethos appeals. These are methods of communicating different types of information so that the audience can more fully understand the intended meaning. They provide methods you can use to clarify vague concepts or events with information that is specific and concrete. As outlined in Jenifer Kurtz’s chapter on “Rhetorical Modes,” they are

- Narration—telling a story or anecdote, often with the goal of helping readers connect emotionally with the main character and/or understand how an event unfolded.

- Description—using sensory details that make a particular setting or object more vivid for readers, so they can more fully picture what it looks like, feels like, and so on.

- Process—giving readers step-by-step details about how something works or how they can accomplish a specific task.

- Illustration and exemplification—demonstrating a concept or idea through the use of evidence or examples.

- Cause and effect—describing why something happened and/or what the consequences of an event or action might be.

- Compare and contrast—helping audiences more fully understand a concept or object by describing how it is similar to or different from something they are already familiar with.

- Definition—giving a statement of meaning for a particular term or idea.

- Classification—organizing parts of a larger whole into categories to help readers understand similarities and differences between them.

As you can see, each rhetorical mode, depending on how it’s used, could be classified as a type of rhetorical appeal. A narrative, for instance, is often used as a pathos appeal—to get audiences to connect with a particular character and the circumstances they are facing more fully and emotionally. Similarly, clear description could be used to compel certain emotions in audiences (a pathos appeal), and it might also be used to provide clarity and imply further logical connections (a logos appeal). The main point here is that so much of the communication we do—in spoken word and in writing—is built around these rhetorical modes, which become the building blocks of larger rhetorical appeals that—if crafted well—help the speaker to meet their communication goals. We’ll look more specifically at the rhetoric of digital writing in a later section, but suffice it to say for now that digital writing is also built from rhetorical strategies, though there are quite a few more tools at your disposal to engage audiences and build meaning.

The final group of communication strategies that we’ll discuss are called rhetorical devices, which refer to a way of using language for persuasive purposes. Whereas the rhetorical modes we discussed above relate more to the content of a message, a rhetorical device is often more about word choice. It’s a way of phrasing a particular idea in order to increase the audience’s engagement as well as their emotional reaction. In fact, rhetorical devices are sometimes called “slanters” because they put a certain spin on a message—either positive or negative—to make audiences feel a certain way. Rhetorical devices are typically emotional (pathos) appeals, sometimes intended to help audiences engage on a deeper level with a topic and sometimes—in the case of a slanter—intended to manipulate their emotions or distract them from the logical (or illogical) aspects of a message.

The list of rhetorical devices is extensive (Merriam-Webster)—way beyond what we could practically study in one chapter—but it might be worth looking at a few examples to demonstrate how common they are and the persuasive effect they can have:

- Simile—a comparison using “like” or “as.” This is a common device that has clear connections to the compare-and-contrast rhetorical mode identified above. However, whereas the mode would provide a deeper discussion of the similarities and differences between two or more things, a simile is a simple phrase and is often used to create positive or negative associations. For instance, saying that a political candidate was “grasping for words like a drowning man clinging to driftwood” puts the politician in a more negative light, making them seem desperate.

- Metaphor—a comparison that doesn’t use “like” or “as.” A metaphor can’t be taken literally, which requires the audience to recognize that it’s a figure of speech, implying a comparison. For example, saying that one of your friends “didn’t pull any punches” in a recent conversation with you is (hopefully) a metaphor. It doesn’t literally mean that your friend was hitting you. It’s a comparison that implies your friend wasn’t trying to spare your feelings.

- Euphemism—making a topic that is negative or neutral seem more positive than it is. For instance, instead of calling someone “stubborn” (a fairly negative term), calling them “tenacious” or “determined” puts a more positive spin on it. Similarly, instead of selling “used cars,” a car dealership will often refer to them as “pre-owned vehicles,” which has a slightly more positive ring to it.

- Dysphemism—making a topic that is positive or neutral seem more negative than it is. For instance, calling one of your teachers a “dictator” would obviously put that person in a more negative light. A person who calls their spouse a “ball and chain” is also using a dysphemism that makes their spouse and their marriage seem confining.

- Hyperbole—extreme exaggeration, typically for dramatic effect to demonstrate the importance or significance of something. Saying that you could have “died” of embarrassment at a particular moment emphasizes the significance of your feelings and would probably garner more sympathy from your audience.

The list goes on. It can sometimes be really helpful to know the various rhetorical devices so that you can identify them when they are used in a conversation. However, more important than knowing the specific terms is being able to recognize how language is used in a given situation to elicit specific emotions and how those emotional responses benefit the speaker. Obviously, not all rhetorical devices are negative. They can be used in positive ways to capture an audience’s attention and demonstrate the significance of a particular idea. Also, when used well, a rhetorical device can be extremely effective in persuading an audience. However, rhetorical devices can be used to manipulate or distract, and when they come across as melodramatic or underhanded, then they have the opposite effect, often diminishing the credibility of the speaker in addition to dissuading the audience. For that reason, understanding how rhetorical devices are used and for what purpose is helpful as you interpret and respond to messages and as you craft your own.

Activity 7.2

Collect a handful of various digital messages. These might include an email you have received, text messages, blog posts, social media posts, and so on. Try to make each one different in terms of the platform and what you perceive to be the purpose of the message.

Now consider the rhetorical strategies that are used in each message. You might begin by simply labeling the broad rhetorical appeals—logos, pathos, and ethos—remembering that a given text could use more than one appeal. Then drill down into each category. Can you identify specific rhetorical modes that are used to engage the audience or clarify information? Can you identify specific rhetorical devices?

Finally, consider whether each message is effective based on its use of the various appeals. Which strategies enhance the meaning and persuasiveness of a given message? Which ones are ineffective because they are unclear, illogical, or clearly manipulative? What other strategies might have been used to make the message more effective?

The Ubiquitous Nature of Rhetoric

So back to where we started: rhetoric is everywhere, all the time. This chapter was designed to demonstrate this point more fully (using a blend of logos and ethos appeals) and to underscore the importance of the messages you send as well as the complexity of a given rhetorical situation. While many situations might call for very intentional and thoughtful attention to the rhetorical elements that should influence the way that a message is crafted and how audiences might react (a marriage proposal, for instance, or a public speech or sermon), there are many rhetorical situations that materialize each day that we are prone to overlook because they might seem insignificant. We might not even identify them as a rhetorical situation because they are so informal, low-stakes, or brief. However, the reality is that every time a message is conveyed to an audience—whether it is intentional or not, whether it is planned beforehand or not—it is a rhetorical situation with an exigence, a purpose, and a reaction from the audience. A quick text message, a wave to someone that you know, and your body language as you sit in class or in a meeting are all examples of rhetorical messages that can result in positive or negative consequences depending on the context of the situation and the audience’s interpretation of the message.

Having a clearer understanding of rhetoric and how it can unfold in both the big and the small moments will, at the very least, help you see how rhetoric functions in your everyday life. In fact, so many of the things that you strive to accomplish rely on rhetoric. All of your social relationships are built on and largely consist of rhetorical messaging. Similarly, your ability to effectively send and interpret messages has a direct impact on whether you pass a class, get a job, pay your bills on time, buy or sell a house or a car, enjoy a night out with your friends, and so on. If you were to track your conversations throughout the course of a day or a week and then consider the rhetorical implications of each one, you’d see that even the most mundane exchange with someone helps you work toward larger goals. Here are some examples of how rhetoric functions in your everyday life:

- To complete a task. You rely on clear messaging with your boss/coworkers and or your teachers/peers in order to complete work tasks and larger projects. You receive messaging that details deadlines and other requirements for assignments, and you send messages in order to clarify those instructions, work with peers/colleagues on projects, and interact with customers. Even minor tasks like renewing your driver’s license or filling a grocery order require rhetorical discourse.

- To forge and maintain social relationships. These are often more mundane, seemingly meaningless text messages and informal conversations that you have—sometimes with close friends and family and sometimes with acquaintances and even strangers. These interactions are also persuasive, meant to facilitate people’s positive impressions of you and to create feelings of connectedness and care. Even minor interactions with strangers, in which you let someone get in front of you at the grocery checkout or you tell the McDonald’s drive-thru attendant to have a great day, are social interactions that encourage goodwill and create momentary connections.

- To express yourself. Often you speak up in order to express an idea or an emotion. Sometimes, this might overlap with other functions of getting work done or forging social connections. Self-expression might seem like a more personal discourse that doesn’t relate to rhetoric, but when you have an audience, it’s rhetorical—often for the sake of being heard and understood. Even when you are expressing feelings and ideas that won’t be positively received by your audience, there is still the underlying goal of being part of a conversation and sharing your perspective.

- To solve problems. Rhetorical discourse can be used to identify a problem and to work through the potential solutions and consequences with others who are involved. This is also a social exchange, since it involves working through different perspectives and finding solutions that will appease everyone.

- To learn. In this case, you receive messages, ask clarifying questions, and produce texts that apply specific concepts in order to develop your understanding of a given subject.

- To receive a personal benefit. You use rhetoric to persuade audiences to act in your favor. Maybe you get pulled over, and you use rhetoric to dissuade the officer from issuing you a ticket. Or you missed an assignment deadline, and you convince your teacher or your boss to let you turn it in a couple of days late.

- To benefit others. In this case, you would speak up in some way to help other people. Maybe you clearly explain a concept or an idea to someone who is trying to learn, so you take the time to help them understand. Or perhaps you defend the viewpoint of a person or a group in order to defend their rights or interests.

These are a few examples of how rhetoric functions in deeper ways in our everyday lives, helping us work toward big-picture objectives in our personal, civic, and professional lives. When put into that larger context, it becomes clear that a conversation is never just a meaningless conversation. There are larger objectives at stake, and having a clear understanding of what those objectives are and how they stem from rhetorical discourse will aid in your success.

Activity 7.3

Track your conversations for an entire day, or maybe several days in a row, even the ones that seem minor. Write down some basic elements of the rhetorical situation—speaker, audience, message, exigence, purpose. At the end, review your data and look for larger patterns in these conversations, perhaps related to the functions identified above or other “functions” or types of objectives that you identify. Many conversions have more than one function, so be sure to give all of the appropriate labels.

Write a brief response that explains the different functions that you identified and how some of the smaller conversations you had work toward those larger goals.

Discussion Questions

- What is a rhetorical situation? What are the key elements that are involved? Can you use those key elements to demonstrate an example of a rhetorical situation you’ve encountered recently?

- What does Bitzer mean when he says that rhetoric can alter reality? How does rhetorical discourse alter reality? How does this view of rhetoric relate to Bitzer’s definition of exigence?

- What does Vatz mean when he says, “Meaning is not discovered in situations, but created by rhetors”? Can you think of an example in which two people might interpret the exigence differently?

- Define kairos and explain how it relates to the effectiveness of rhetorical discourse.

- What are some possible constraints that can influence the success of a message?

- Define the three rhetorical appeals and give examples of each one.

- What does it mean that the rhetorical appeals might overlap in a particular message? Can you give an example?

- What are the rhetorical modes of discourse? How do they relate to the rhetorical appeals?

- What is a rhetorical device and how does it relate to the rhetorical appeals? Define two to three rhetorical devices that aren’t defined in this chapter but are identified on the Merriam-Webster website. Give your own example for each device that you select.

- How do even small conversations fit into the larger definition of rhetoric? How does all rhetorical discourse work toward larger objectives?

- The definition of rhetoric given by the Department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at San Diego University says that “we shape and are shaped by language.” Explain what you think that means.

Sources

American Rhetoric. “Scholarly Definitions of Rhetoric.” American Rhetoric, n.d., https://www.americanrhetoric.com/rhetoricdefinitions.htm.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 1, 1968, pp. 1–14, http://www.arts.uwaterloo.ca/~raha/309CWeb/Bitzer(1968).pdf.

Department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies. “What Is Rhetoric?” San Diego State University, n.d., https://rhetoric.sdsu.edu/about/what-is-rhetoric.

Eidenmuller, Michael E. “Scholarly Definitions of Rhetoric.” American Rhetoric, 2021, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/rhetoricdefinitions.htm.

Kurtz, Jenifer. “Rhetorical Modes.” Let’s Get Writing! edited by Ann Moser, Virginia Western Educational Foundation, Inc., 2018, https://pressbooks.pub/vwcceng111/chapter/chapter-5-rhetorical-modes/.

Pantelides, Kate. “Kairos.” Writing Commons, n.d., https://writingcommons.org/article/kairos-2/.

Rapp, Christof. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/#StruRhet.

Merriam-Webster. “31 Useful Rhetorical Devices: ‘Simile’ and ‘Metaphor’ Are Just the Beginning.” Merriam-Webster.com, n.d. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/rhetorical-devices-list-examples.

Mele, Kate. “Rhetorical Situation, Exigence, and Kairos.” In Introduction to Professional and Public Writing. Pressbooks, 2020. https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/wtng225/chapter/exigence-and-rhetorical-situation/.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 15 Mar. 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/#StruRhet.

Vatz, Richard. “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 6, no. 3, Summer 1973, pp. 154–161. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40236848.