11 Rhetoric and the Ideological Turn

Think about your favorite story. It might be a movie or a novel or even a memoir. Now think about the main things that you like about this story. It might be the plot twists or the underlying premise of the story that engages your imagination. Most likely, if it’s your favorite story, you have some sort of connection with the protagonist—the main character of the story, whose internal thoughts and feelings are revealed as the plot unfolds and with whom the audience is invited to identify. When that main character experiences loss or when obstacles emerge that prevent our “hero” from reaching their goals, we feel their pain and anger. As the climactic moment approaches, we feel anxiety as we hope for the best but worry about defeat. And as is the case for many narratives, we rejoice with the main character at the end when, against all odds, they experience success.

One of the most important, yet difficult, aspects of a good story is characterization, referring to the level to which a character’s personality, motivations, feelings, and perspectives are revealed. A well-developed character creates an emotional connection with the reader, who begins to empathize with the character’s struggle and invests time and emotional energy into their story. Even the villain of an engaging story can be developed in such a way that the audience begins to understand and even sympathize with their situation. They become more than the greed, arrogance, or cruelty that might have characterized them at first. On the other hand, a flat character can ruin a story because they don’t come across as genuine. Instead of fleshing out that character’s complex experiences, emotions, and motives, the story focuses on a singular aspect of the character, leaving the audience with very little understanding or concern about what happens to them.

Unfortunately, the digital realm has a terrible way of flattening people so that all we focus on is a singular aspect of their identity, whether it’s their political affiliation or their stance on a particular issue. Alongside political tensions that have increased significantly since the pandemic, ranging from mask mandates to vaccines to race relations to sexual identity, some people are very quick to attack anyone who opposes their viewpoint, condemning them for being selfish, greedy, racist, overly sensitive, or intentionally divisive (Jørgensen et al.). This is especially true in online spaces where tensions quickly escalate with a series of posts designed to cut the other side down. Seldom do people listen to try to understand the full complexity of another person’s perspective—the experiences, emotions, and motives that inform their position on a topic. Rarely do people consider the larger ideologies, assumptions, and social contexts that inform their own position. We tend to assume that we are in the “right,” and that the other person, through their own ignorance and immorality, is clearly wrong.

Many people argue that our democracy has lost its ability to discuss important issues in a rational and productive way. Henry Giroux argues that as digital media emerged with an emphasis on target marketing, individualism, and algorithms that insulate users into an echo chamber of similar views, we’ve lost our focus on public values and relationships necessary for a healthy democracy. He says, “Instead of public spheres that promote dialogue, debate, and arguments with supporting evidence, we have entertainment spheres that infantilize almost everything they touch, while offering opinions that utterly disregard reason, truth, and civility” (10). Similarly, James Klumpp and Thomas Hollihan point to our “current moment” as an especially critical time to refocus on “democratic values” and the intellectual practice of analyzing public discourse to understand the rhetorical strategies and ideologies that influence our moral development and our behaviors. In fact, more than 30 years ago (1989), Klumpp and Hollihan wrote their landmark essay “Rhetorical Criticism as Moral Action,” arguing that rhetorical critics must look beyond the persuasiveness of a message; they must also interrogate the moral implications—the effect that a message has on the experiences and opportunities of real people. In their 2020 follow-up to that article titled “Rhetorical Criticism and Moral Action Revisited,” Hollihan and Klumpp reiterate the importance of their original argument in the context of increasing political turmoil:

The current moment prompts us to pause to evaluate how well academic critics are honoring democratic values and promoting a democratic culture. Democratic values, particularly comity and broad participation, have been under assault for the past several years in the United States and many of the same threats are undermining democracies around the world. Among the central values requiring attention and defense in our democracy are, in fact, values which shape our rhetorical interactions with our fellow citizens. The moral and rhetorical imperatives we pointed to 30 years ago have merged in ways beyond a theory of criticism; today’s moral crisis fully implicates the rhetorical. (334)

This chapter endeavors to make explicit connections between public discourse, rhetorical strategies of persuasion, and ideologies that demonstrate our values and inform our actions. It emphasizes both critical and rhetorical literacy. In fact, language and ideology are deeply intertwined, constantly revealing our values, our beliefs about what is “true,” and the way that we define ourselves in relation to other people (Berlin). Understanding this connection and doing the intellectual work of analyzing the rhetorical strategies and ideologies embedded in public discourse equips us to be more discerning about the information that we like, share, repost, hyperlink, and ultimately accept as fact. It puts us on the defensive against misinformation and disinformation as well as the underlying motives to manipulate our emotions and destroy our sense of reality. It allows us to examine our own messaging and the ideologies that are embedded therein. And it creates a habit of careful analysis and reasoned engagement that helps us move toward “vibrant public spheres and a political culture that invites deliberation, discussion, debate, and dissent” (Hollihan and Klumpp, “Rhetorical Criticism and Moral Action Revisited” 335).

Learning Objectives

- Understand the connection between rhetoric and ideology.

- Learn how to analyze rhetorical discourse for the ideologies embedded within.

- Be able to identify rhetorical strategies that are used to create emotional reactions in an audience and create division against an opposition.

- Learn about Burke’s theory of identification and how it can be both a positive communication tool as well as a tactic of manipulation.

- Consider the way that ideology in language links to motives and compels people to behave in particular ways.

- Understand the shifts in rhetorical analysis as a result of the Ideological Turn and how these shifts are still relevant today.

- Consider the effect of digital media on people’s ideologies and their ways of engaging with controversial issues.

- Be able to identify the logic of an augment based on its premises.

- Understand the principle of a logical fallacy and be able to identify weak and illogical arguments.

- Consider how Burke’s theory of the “comic corrective” can be applied to your own way of framing specific issues.

Rhetoric and Ideology

In order to make the connections between rhetoric and ideology, some review might be in order. Remember that rhetoric is about effective communication, and often our communication goals center on persuasion—compelling the audience to react in a certain way. It’s about prompting specific thoughts and behaviors. However, not all persuasion is explicit. There isn’t always a call to action at the end of a message. Not all persuasion centers around a central claim in which the speaker outlines clear and specific reasons. When we think about the ways that ideologies are embedded in our language, the focus tends to be on the subtle nuances and the beliefs that are implied. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines ideology as “a manner or the content of thinking characteristic of an individual, group, or culture.” These are the foundational beliefs we have about the world—what we hold to be “true” or “right” or “normal.” These beliefs are implied in our communication with others, and often we assume that others do or should share the same beliefs. We tacitly, perhaps even unconsciously, impel the audience to adopt these same beliefs.

For instance, a couple that has been dating for a while will often have different family members and friends ask, “When are you two getting married?” It’s a simple question that isn’t an explicit argument, but it does imply that the couple should be thinking about getting married. There are also some assumptions embedded in this question—that marriage is a good thing, that finding a partner and getting married should be a priority. Culturally, there are also a lot of assumptions built into what “marriage” means—that it’s typically between man and a woman, that most married couples have children, that married couples eventually buy a home and conform to established gender roles. Of course, not all romantic relationships are this way, particularly in the last few decades as ideologies have begun to shift, but couples who resist the more conventional system of marriage are still met with questions and well-meaning concern because their relationship doesn’t conform to what seems “normal.”

You can probably see how different ideologies can create discord. The current political landscape, with so much tension and debate surrounding numerous issues, has a lot of people worn out. They’re tired of rehashing the same arguments about the same issues and confronting the emotional tensions that coincide with such conversations. They might say things like “I don’t want to discuss anything political” or “Why does everything have to be so political?” These statements signal their fatigue over the underlying political agendas (and ideologies) and our tendency to reduce complex problems to a matter of Republican versus Democrat. However, on a much deeper level, everything is political, not in the sense of right versus left but in the sense of demonstrating our beliefs, values, interests, and identities, which connect us to certain groups of people. In his book Politics for Social Workers, Stephen Pimpare devotes an entire chapter to the reality that “everything is political.” He says,

Politics is the way that we make people aware of problems, introduce ideas into the public sphere, create frameworks for thinking about issues and their relative importance, structure debates about policy, frame defenses of justice and fairness and equity, and build consensus for change. (49)

Pimpare goes on to explain that politics has a fundamental effect on the quality of our lives and our communities and that even when we do retreat from political debate, there are still political implications of reinforcing the status quo.

Similarly, our language, even when we veer away from hot-button political topics, is inherently connected with our ideology—our conception of how the world is and how it should be. At the height of the “Ideological Turn” in rhetoric, when scholars like Philip Wander and James Berlin argued that everything is political and there is no way to avoid ideology even in the most “neutral” spaces like a classroom, Berlin argued that our language is never value-free: “Conceived from the perspective of rhetoric, ideology provides the language to define the subject (the self), other subjects, the material world, and the relation of all of these to each other. Ideology is thus inscribed in language practices, entering all features of our experience” (Berlin 479). In other words, all of our communication points toward our values, beliefs, relationships, and identities—what we hold to be “true,” “right,” and “normal.” If we are considering the ideologies embedded in a message, we’d look beyond the immediate benefits to the speaker, also considering what types of ideas and what types of people are valued.

Let’s look at another example. Within the last several years, especially following the COVID-19 pandemic, the topic of mental health has become more prominent and more normalized as people are increasingly aware of the importance of this issue. Whereas the idea of seeing a therapist used to be highly stigmatized, signaling that someone was “crazy” or somehow inadequate, it has become much more commonplace for people to openly discuss their mental health needs and personal strategies. Much like going to a physician for an annual checkup is considered to be a normal, beneficial practice, having a counselor and implementing mental health strategies has become a more “normal” aspect of personal wellness. This means that when someone states that they are overwhelmed by a project and need more time to have it completed or that they are taking a “mental health” day, they are invoking a larger set of values and cultural shifts. They are asserting the value of their own mental health, but they are also tapping into bigger conversations and historical contexts about the importance of mental health in general, and they want their audience to respond in ways that confirm that value and promote further awareness and sensitivity. The ideology is embedded in the way that the speaker implies the reality that mental health (along with the person with the mental health needs) should be prioritized. However, someone who responds that these issues are in a person’s head or that they are being overly “sensitive” or “fragile” is invoking a different set of values, de–emphasizing the importance or the reality of mental health challenges.

Though this is just one possible example, it demonstrates an interesting dichotomy that characterizes much of our everyday speech patterns—an “us” versus “them,” a “right” versus “wrong,” and a “real” versus “imagined” way of framing a topic and our own position, selected from a range of possible perspectives. We are more likely to be persuaded and to persuade others when issues are framed from the perspective of an in-group versus an out-group, compelling audiences to identify with and make choices that validate their belonging to the in-group. In his book A Rhetoric of Motives, Kenneth Burke calls this phenomenon “identification” and “consubstantiation.” Though we are all separate individuals, we use language to mark our identity as part of select groups (i.e., discourse communities) with common interests, values, and goals (i.e., areas in which we are “consubstantial”). Consider, for instance, a sports team, which is its own discourse community imbued with unique communication patterns. Members of the team share a common goal of advancing their skills and having a successful season, and to that end, much of their conversation is about game strategy. This discourse community is defined not only by the topic of conversation but also the specialized terms that are used and the genres where communication happens—that is, team huddles, locker room speeches, group chats, and so on. Going back to our discussion about ideology, if we were to take a closer look at these discussions, we’d certainly discover some underlying values and assumptions of what is right or beneficial— perhaps teamwork, physical fitness, or competition. And according to Burke’s theory of identification, each individual on the team demonstrates their belonging through a series of rhetorical choices, such as their participation in the team huddles and their use of the accepted jargon. It even includes the sports gear and apparel they wear. They conform to the established communication patterns in order to persuade others that they are “normal,” that they are part of the group. And it is that sense of belonging and common interest that increases their likelihood of adopting specific perspectives and behaviors that align with the in-group.

It’s not difficult to see how language can be used to create solidarity with an in-group that is “right” in its view of “reality,” purposely set up against an out-group, whose complex experiences, perspectives, and beliefs are oversimplified and dismissed. Burke originally considered his theory of identification as a positive phenomenon that would create empathy and mutual understanding for perspectives different from our own. He said, “Identification is compensatory to division. If men were not apart from one another, there would be no need for the rhetorician to proclaim their unity” (A Rhetoric of Motives 22). However, he also warned that identification could be twisted, used as a weapon to create division. His “The Rhetoric of Hitler’s ‘Battle’” (from the book The Philosophy of Literary Form) provides a rhetorical analysis of how Hitler used identification—the “us” versus “them” framework—to create solidarity among the Nazis and dehumanize the Jewish population. In a similar way, Thomas Hollihan and James Klumpp, in both their 1889 and their 2020 essays, analyze the rhetorical discourse of authority figures to show how identification is a persuasive tactic that invites the audience to be on the “right” side of an issue by establishing common values and perspectives, pitted against a common enemy.

While language is often an intentional mechanism used to further an agenda and reinforce particular ideologies, it’s important to point out that ideology exists in our language, even if we don’t have a particular agenda in mind. Our selection of words and topics that merit discussion and our way of framing those issues will always imply a set of values and beliefs. Consider, for instance, our previous discussion about Philip Wander and the second and third personas implied in a message. There is the ideal audience who is pushed to the center, whose beliefs and perspectives are valued as “normal” or idea. The third persona is the group in the audience who is pushed to the periphery, either intentionally or unintentionally, by the speaker because they don’t share particular qualities, perspectives, or abilities. For instance, the song “Stand by Your Man” begins with the following lyrics: “Sometimes it’s hard to be a woman, givin’ all your love to just one man.” The message is clearly geared toward women, but it makes some assumptions about what it means to be a woman (second persona)—someone who is devoted to a man. However, if we consider the third persona—members of the target audience who are marginalized or ignored by the message—we’d see that there are lots of women who don’t fit this ideal because they aren’t (and possibly don’t want to be) in a relationship with a man. Chances are the song wasn’t intended to alienate these members of the audience. Nevertheless, like all language, it promotes a certain perspective about what is true or normal.

Similarly, the way that we respond to the ideology in a message tends to be automatic and deeply ingrained, reflecting our own core beliefs that we are often unwilling to question or reexamine. As opposed to forming a logical response, we fall back on identifications and familiar ways of thinking and seeing. According to Stephen Pimpare, this is even more true the older that we get:

By the time we are adults, we have constructed a robust set of positions and beliefs. When thinking about the political world, we begin with those beliefs, those inherent biases, and then work backward (often unconsciously) to fit whatever facts we are being presented with into that preexisting schema. Our minds use this motivated reasoning to protect us from cognitive dissonance—information that could unsettle our established beliefs or worldview. As a consequence, our brains literally process information differently depending on whether it fits with or challenges a preexisting belief.…This helps explain why presenting people with evidence showing that they are incorrect about something can make them less likely to change their minds—they double down on their position, adopting a defensive crouch. (146)

The point is that our language is steeped in ideology, sometimes in subtle but nevertheless powerful ways. As we’ll discuss in the next section, language does more than reflect reality. Rhetoric is so important because of its ability to shape reality, to frame a topic in particular ways that change how an audience understands an issue and affect the choices they make. It has tangible consequences in the world.

Activity 11.1

Using Burke’s theory of identification, consider the different ways that you signal your belonging to different groups. This might be as simple as the type of clothing that you wear to different events or the way that you position yourself in a room of people. It might also include activities that you’re a part of, images or logos that you display on your car or walls, and words and phrases that you use in various contexts.

Activity 11.2

Choose an online text that advances a particular viewpoint or perspective. It doesn’t have to be an explicit argument, nor does it have to be long. It could be a video, social media post, blog article, or speech. Read and annotate this text with identification in mind. Some questions to consider include the following:

- Who is the intended audience?

- What seems to be the purpose(s) of this text?

- What are some things that the audience is invited to identify? It might be a perspective, a common goal or problem, or an interest, belief, or value. Underline specific sentences where this occurs.

- If applicable, what are ways that other people—outside the in-group—are portrayed? Underline specific words and phrases and consider their effect on the audience.

- How successful is the text in persuading the audience?

Rhetoric and Moral Action

A common misconception is that words don’t matter, that they are nothing more than air. Kids on the playground like to say, “Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” Teenagers and even adults when confronted by dialogue they don’t like will shrug and say, “Whatever,” to show they aren’t affected at all by what was just said. But the whole purpose of this unit on rhetoric is to show that words do matter. Through the power of language, ideas take shape, personal connections form, perspectives change, emotions swell, and people take action. Ideologies inform policies, legislation, legal proceedings, codes of conduct, and individual behaviors—all things that have tangible effects on people’s lives. As discussed above, Hollihan and Klumpp wrote two essays focusing on the moral consequences of rhetoric, arguing that rhetorical criticism is about more than unpacking the underlying purpose and rhetorical strategies utilized to persuade an audience but that it should also consider the ethical implications of the message: How moral are the underlying motives of a message? How will it affect audiences in positive or negative ways? What actions does it compel, and how do those actions affect different groups of people?

Morally engaged critics owe our democracy attention to the multiple forces at work in discursive practices that mislead the public, limit their ability to act in their own best interests, transform their disagreements into hostile uncooperative factions, and reallocate political, economic, and social power from the ordinary citizens to increasingly wealthy elites. Such citizen critics, when fervently but soundly engaged, seek to bend the curve of history in a new direction in which aroused public and resilient institutions regain democratic sensitivities and reclaim democratic civic virtues. (Hollihan and Klumpp, “Rhetorical Criticism as Moral Action Revisited” 334)

In their original 1989 essay, Klumpp and Hollihan discussed three shifts in rhetorical criticism that put the focus more squarely on the moral consequences of rhetoric, and these ideas are still incredibly relevant today. This first shift relates to our understanding of rhetoric as being situated in a cultural and historical context. An individual speaker has a purpose and a unique way of persuading an audience, but their words are always part of a larger “social milieu” that significantly enhances the meaning of their words and the effect on the audience. “The question of ‘Who is the author?’ is thus answered with attention to the forms of the culture from which the speaker draws, or the speaker becomes interesting as an authority who speaks for society even as s/he speaks to society; thus the shift to rhetor as socially grounded” (88; emphasis original). In other words, a speaker presents ideas and perspectives to an audience, but they also use language that is inscribed with cultural significance, carrying a socially agreed upon set of values and emotional responses. Michael Calvin McGee coined the term “ideograph” to refer to words and phrases that are imbued with meaning to generate particular responses from an audience. They connect to larger ideologies and can be used in rather vague and abstract ways to induce a reaction from an audience. For instance, the word “equality” is an ideograph, deeply embedded in historical events and cultural values, and when used as part of a message—even when its meaning in that specific context is ill-defined—it tends to automatically garner attention and support. In summary, the first shift in rhetorical criticism examines the moral consequences of a message by considering the larger cultural and historical significance of the message and the way key words and phrases are used to invoke particular reactions.

The second shift identified by Klumpp and Hollihan pertained to the power of rhetoric to create meaning, informing the way that people perceive a topic or event. Instead of seeing rhetorical discourse as a reflection of meaning that has already taken place as part of an event, scholars began to see the power of rhetoric to create meaning through selections (and deselections) of details and word choice. It shapes our way of seeing and knowing about the world, our sense of reality about how things are and how they should be. According to this view, “rhetoric transform[s] material contexts into social order” (Klumpp and Hollihan, “Rhetorical Criticism as Moral Action” 89). It doesn’t reflect a fixed reality; it creates a sense of what is “real” or “true.”

The third shift in rhetorical criticism put more focus on the motive of the speaker—their intended outcome regarding the way that the audience perceives and responds to reality. You’ll recall from chapter 7 in this textbook that all rhetoric is grounded in an exigence—an imperfection or problem that the speaker hopes to remedy as a result of rhetorical discourse. In that view of rhetoric, only the audience—through their response to the message—can resolve the exigence. Rhetoric compels action, and it’s through this intended action that the ideology and ethical implications of a message can be evaluated.

The point in all three of these shifts is that rhetoric has a significant impact on the lived experiences and material reality of people in the world. Ideology has a direct influence on our views of right and wrong, shaping everything from parenting strategies to university admission standards to hiring practices to school curriculum to legal proceedings. And because language is the vehicle through which ideologies are established, language is the place where we begin to examine social values and the material consequences of rhetoric.

The Effect of Digital Media

Much has changed since the Ideological Turn of the 1980s, largely as a result of the prevalence of digital media as the primary means through which people receive information. It used to be that people received most of their news from newspapers, which had more information and were organized as an inverted pyramid with the most important information near the beginning, which made it easier for readers to process information (Xenos et al. 709). What’s more, the format of the newspaper allowed readers to take in information at their own pace, perhaps going a bit slower and rereading important information. The fact that it took more mental energy meant that readers concentrated more and typically processed information on a much deeper level than they would have from a television news story (Xenos et al. 709).

As you probably guessed, as digital media emerged and grew in popularity, newspaper readership diminished. According to recent statistics from the Pew Research Center, the circulation of U.S. daily newspapers was 55.7 million in 2000 and has decreased dramatically in the last two decades, down to 24.3 million in 2020. In contrast, 68% of Americans report that they get their daily news from social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, X, and Reddit (Shearer and Matsa). This number is especially high considering that so many survey respondents in Shearer and Matsa’s study admit that they believe much of the information they get on social media is “inaccurate,” but they continue to use it for news information because of the “convenience.”

In addition to the misinformation that is so prevalent online, disinformation and misinformation permeate digital media, intended to produce division and distraction. Market segmentation and algorithms create an echo chamber effect that prevents users from accessing the full spectrum of perspectives on key issues, creating a false sense of “reality.” All of these distortions and cognitive shortcuts further entrench people in preset biases and beliefs and make them more resistant to anything outside of their own point of view. As Giroux argues, “Numbed into a moral and political coma, large segments of the American public and media have not only renounced the political obligation to question authority but also the moral obligation to care for the fate and the well-being of others” (14). Positive engagement in today’s digital realm requires users to proactively step outside of their perspective, purposely seek out alternative voices, and engage thoughtfully with rhetorical discourse to understand the underlying ideologies and social consequences.

Logical Fallacies

The discussion regarding language, ideology, and underlying agendas points to an important skill that will help you discern the logic of an argument without getting swept away in language that is designed to distract and deceive: the ability to identify logical fallacies. We’ve talked at length about rhetorical strategies (pathos, ethos, logos) and rhetorical devices that are intended to persuade an audience. In many instances, these are sound strategies that present evidence and help audiences connect emotionally with a specific point of view. However, many arguments aren’t sound. Whether intentionally or not, they present a line of reasoning that isn’t logical. Sometimes, there’s no “reasoning” at all. Instead, the rhetor uses emotionally charged words, hoping to evoke an emotional response. These are called logical fallacies, which the Purdue OWL defines as “illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points…often identified because they lack evidence to support a claim.”

We could spend an entire textbook discussing argumentation and logic. For now, suffice it to say that a sound argument is one that employs logical reasoning. It draws a conclusion (the position or claim) based on evidence and/or principles that are laid out for the audience to demonstrate that they are true and that they logically lead to the conclusion. In the case of inductive reasoning, specific events or examples are used to draw a general conclusion (Miller and Poston). For example, if you fail an exam every time that you cram the night before, you’d probably eventually conclude that cramming for a test doesn’t work, and you’d find a different way to study. In contrast, deductive reasoning (Miller and Poston) begins with a general idea or principle (often called a major premise) and applies it to specific circumstances (the minor premise) in order to draw conclusions. For example:

- Major premise: All birds lay eggs.

- Minor premise: A parakeet is a bird.

- Conclusion: Parakeets lay eggs.

Of course, arguments about social and moral issues can get a lot more complicated than that. However, once someone gives a reason that supports their position on an issue, then it’s easier to examine the premises that led to their conclusion. For instance, if one of your professors says, “I don’t accept extra credit because it undermines student learning,” then you can examine the major and minor premises that led to that conclusion to discuss if they are really true and if they inevitably lead to the conclusion:

Major premise: Anything that undermines student learning in a classroom is bad. (Most people would probably agree that this is true given that the primary purpose of a class is learning, though some people might have different ideas about how important a particular class really is and what “learning” looks like.)

Minor premise: Extra credit is an example of something that undermines student learning in a classroom. (This is especially open for debate. Some people might argue that it depends on the activity that leads to extra credit. Some extra credit assignments aren’t very challenging or meaningful, but some can do quite a bit to engage students with course material and further their understanding of particular concepts.)

Conclusion: Extra credit in the classroom is bad.

You can see how examining the premises that lead to a conclusion can be really useful in deciding whether they are true and whether they are valid (i.e., they logically lead to the conclusion). Premises are also helpful in examining the underlying values of an argument. This argument about extra credit is obviously valuing the importance of student learning and the integrity of the grading system. That doesn’t mean that this teacher doesn’t value students’ mental health or retention rates, but it does imply that when considering their policy regarding extra credit, they are prioritizing student learning. The reasoning behind an argument will help you uncover the beliefs and values implied in that position, which makes it possible for you to analyze the implied ideologies and your own position on the issue.

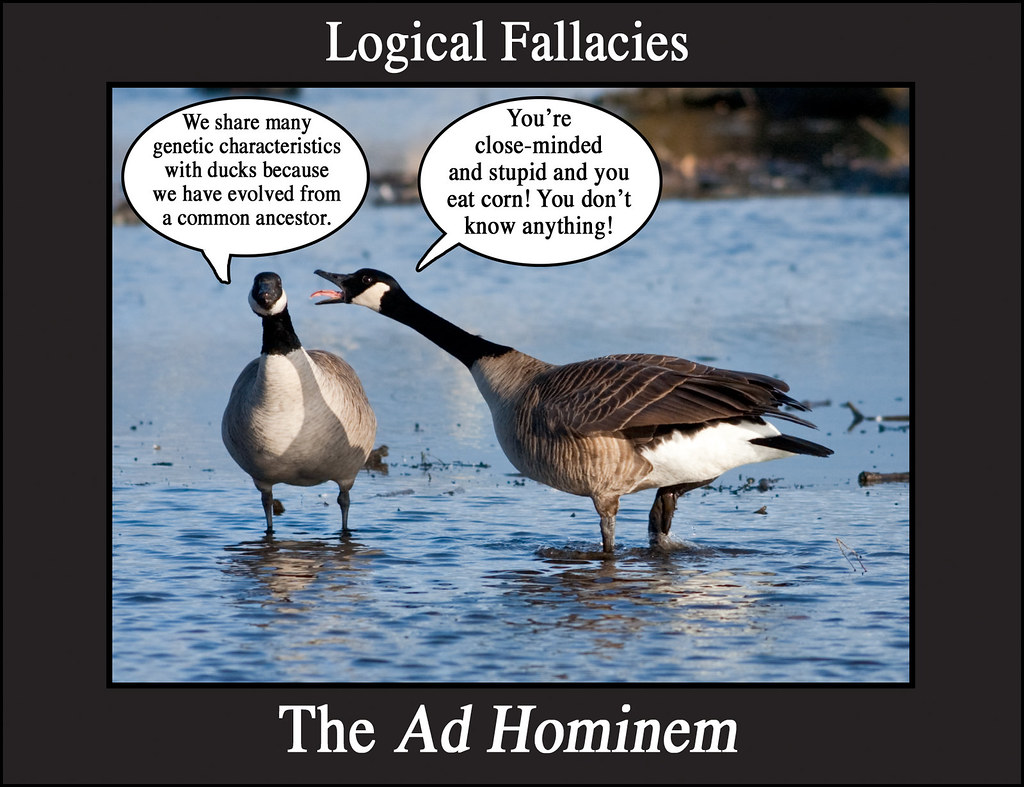

A logical fallacy is so named because there is an error in logic. The premises either aren’t stated or they don’t logically lead to the conclusion. There are too many fallacies to name here, but many resources exist that give a more exhaustive list of the fallacies (LogicalFallacies.org). For now, let’s focus on a few that are fairly common, especially in heated discussions intended to shut down the opposition instead of engaging meaningfully with the issue.

- Hasty generalization. This is especially common with inductive arguments that are built from specific examples. A hasty generalization comes to a general conclusion based on insufficient evidence—sometimes from just one or two examples. If, for instance, you talk to three women and they all say that they love cooking, it would be a hasty generalization to therefore assume that all women love cooking. It’s easy to see how this could lead to stereotyping and prejudice.

- Ad hominem. This Latin term refers to arguments that attack a person instead of refuting an idea or position. These arguments often resort to name-calling or statements that attack a person’s character, thereby ignoring the issue at hand and the premises that led to a specific conclusion. Many political ads resort to this type of fallacy. They assert that the opposing candidate is lazy, underhanded, or in some way unfit for office, which is a way of sidestepping deeper discussions about key legislative or fiscal issues.

- Straw man. This type of argument misrepresents the opposition in some way, often by making their reasoning look weak or immoral. The speaker can then easily “refute” this false account of the opposing view instead of engaging with their stronger reasons. For instance, if someone opposes a tax referendum that would increase teacher pay, it would be a straw man fallacy to say that the person hates teachers or doesn’t care about education.

- Bandwagon. The arguer claims that a particular position is the “right” one simply because it’s the most popular. Saying that we should get rid of speed limit laws because nobody follows the speed limit is an example of a bandwagon fallacy.

- Post hoc (also called false cause or causal fallacy). In this instance, an arguer assumes that since one event happened before another, the first event caused the second event. There might be a correlation between the two things (often occurring together based on a range of complex factors), or they might not be related to each other at all. A valid argument must demonstrate how one thing causes another. For instance, if you had Fruit Loops for breakfast and then got an A on an important test, it would be a post hoc fallacy to say that the Fruit Loops caused you to ace the test. Certainly, it might have helped that you had breakfast (a correlation), but other factors like how well you studied, how well you slept, and how much you were able to focus during the exam would also have to be taken into account.

- Appeal to pity. This type of argument attempts to persuade an audience based on making them feel sympathy or pity. Using your puppy-dog eyes to convince a friend or family member to lend you money is an appeal to pity.

- Appeal to authority. This fallacy claims that a position is the right one because an “expert” on the subject agrees. However, in this case, the person’s expertise is not relevant to the issue at hand, or it’s exaggerated. Having a celebrity or public figure endorse a brand of detergent is an example. While this person is popular and may have expertise on certain subjects, they aren’t an expert on detergent and aren’t qualified to make a credible claim.

- Circular argument (also called “begging the question”). The term refers to the fact that an argument makes the same (or a similar) statement for both the premise and the conclusion. In other words, the argument doesn’t develop clear reasons; it simply restates the conclusion in different ways. For instance, saying that we shouldn’t enforce the death penalty because it’s wrong to put a criminal to death is a circular argument. The reason and the premise are saying the same thing, and there isn’t any explanation about why the death penalty is wrong.

- False dilemma. In this situation, the arguer makes it seem like there are only two possible options or positions for a particular problem or issue, ignoring that there are other—often more reasonable—alternatives. For instance, to say that you can only afford a new car if you get a second job would be a false dilemma because it ignores all of the other financing options.

- Slippery slope. This type of argument is based on cause and effect, identifying a highly improbable sequence of events that will unfold following a specific decision or starting point. It has the “snowball effect” of making a problem seem really big and potentially out of control if we make the wrong decision. It would be a slippery slope if you say that you can’t miss one homework assignment because it will lead to more and more missed assignments and failed tests, causing you to eventually fail out of school and end up homeless on the street.

- Equivocation. An equivocation uses vague language to confuse listeners, to make the other side look guilty, or to avoid telling the truth about a topic or event. For instance, if you said you had a healthy lunch because you had a salad, your audience might feel deceived if they later discovered you had a taco “salad.”

The list goes on. Probably many of these seem pretty familiar, reflecting the types of statements you’ve seen people make in social media posts, interviews, or even political debates. For our purposes, it’s not that important that you memorize the entire list of fallacies. What’s more important is that you recognize an argument (especially if it’s your own) that isn’t logical, that relies on these strategies to trick or manipulate the audience in some way, or that lays out illogical premises that don’t match the conclusion. While these fallacies might seem obvious, people are often vulnerable to logical fallacies when the argument aligns with their cognitive biases—their preconceptions and tendencies to oversimplify complex situations and ideas. Because of their own ideologies, they take shortcuts when presented with information that confirms their own assumptions, which means they don’t take the time to examine the logic behind certain arguments. That’s why logical fallacies are often effective, even though they might seem so obvious.

Activity 11.3

Review the information about inductive and deductive argumentation. Practice writing your own inductive argument, beginning with a set of examples and building toward a conclusion, as well as a deductive argument that lays out general premises to make a statement about a specific situation.

You should also practice deconstructing an argument statement, which is a statement that gives both a claim and a reason. It can be a statement that you make up or that you find online. See if you can use that statement to construct the major and minor premises that led to that claim and then evaluate whether or not you agree that the premises are true and that they automatically lead to the conclusion.

Activity 11.4

This YouTube video has examples of logical fallacies from various television shows and commercials (Brown). It names each type of fallacy before showing the clip with the example. Review the clip and then see if you can explain the fallacy in each example. In other words, what makes a particular clip a slippery slope or an ad hominem?

Alternatively, you can find your own clips or make up your own examples of logical fallacies and take turns with other students to see if you can guess which logical fallacy they are using.

Raising Your Awareness

The point of this chapter is to help you raise your level of consciousness when it comes to the ideologies that are embedded in the language that we use every day and to be equipped to logically and rationally engage in discussions with people about right versus wrong. On one hand, this is an internal exercise that first and foremost should challenge you to examine your own values and beliefs, how those ideologies are communicated through language, and what the consequences are as you interact with other people who listen and respond to your words. At the heart of rhetorical analysis and our discussion of rhetoric as moral action is a focus on people. Certainly, that means understanding your own perspectives and experiences and how that has led to specific opinions, viewpoints, and behaviors, but it also means seeking to understand the perspectives and lived experiences of other people, especially those people who are vastly different from you in some way. Whereas our tendency is to flatten the personhood of people in “out-groups,” who might seem far removed from our daily lives, true analysis (and problem-solving) requires you to ask questions and seek to more fully understand the complexity, the value, of other people and their perspectives.

In one of his most classic theories, Kenneth Burke identifies “systems of meaning” that people use to frame the “human situation.” “Out of such frames we derive our vocabularies for charting of human motives. And implicit in our theory of motives is a program of action, since we form ourselves and judge others (collaborating with or against them) in accordance with our attitudes” (Attitudes 92). Burke says that one popular way of framing a situation is through the lens of victim and villain, thereby setting up our position on the side of good in the battle against a clear enemy. As we’ve already discussed in this chapter, this is a very common strategy used in rhetorical discourse to rally support and ultimately villainize anyone with an opposing opinion. Burke identifies this tendency as scapegoating when we villainize members of the out-group and blame them for problems outside their control (Permanence and Change). Fortunately, Burke points to another frame—the “comic corrective,” which operates on a higher level of consciousness to see the misguided notions of the victim/villain dichotomy. Accordingly, the comic attitude “should enable people to be observers of themselves, while acting. Its maximum would not be passiveness, but maximum consciousness” (Attitudes 171). This is not so much a comedy in the traditional sense, as if you’d be laughing with amusement. It’s more about recognizing the inherent limitations in all of human thinking. As Jessica Chaplain writes, “Comedy involves the recognition of a shared humility in that all people, no matter how much they do know, cannot know everything. Comedy requires the ability to recognize and describe human foibles and mistakes in non-essentializing terms” (5). The point, then, is to use Burke’s theory of “identification” to find connections and common ground with other people and to find ways to rise above the dichotomous ways of thinking, speaking, and being that focus solely on “right” versus “wrong” or “good” versus “evil.” The world we live in and the people we encounter are far more complex.

Activity 11.5

Write a reflection about your own way of framing the human experience. Are there any situations in which you tend to simplify the issue into the victim versus villain dichotomy? What might it look like for you to take more of a comic corrective approach?

You can also think about issues in which you already have a comic corrective approach. What are these issues? Do you find that other people tend to use the victim versus villain frame when discussing these issues? How might you respond to further the conversation in productive and positive ways?

Discussion Questions

- The chapter gives several ways that people tend to “flatten” the opposition and oversimplify opposing viewpoints. Discuss some of the theories used in the chapter to explore this phenomenon. What is the danger of oversimplifying alternative perspectives?

- In their 2020 article, Hollihan and Klumpp argue that our current historical context is a critical moment to reevaluate public discourse and the way that we engage with debate. What do they mean by this? What examples can you provide? In what ways has digital media exacerbated political turmoil and division?

- Define ideology. Describe how ideology is embedded in the language that we use every day. Why do scholars like Berlin and Wander argue that it’s impossible to have rhetoric that is neutral?

- Explain Burke’s theory of identification. How is language often used to create identifications with an audience that will shape their thinking and compel specific behaviors?

- How does Pimpare say that our brains process information differently when we are confronted with information that contradicts our preexisting beliefs?

- This chapter discusses three shifts in rhetorical criticism during the Ideological Turn of the 1980s that put the focus on the ethical consequences of rhetorical discourse. What are those three shifts? How does each one relate to ethics? In what ways is each shift still relevant today?

- Describe the difference between inductive and deductive reasoning and give your own examples of each one.

- What are the qualities that make an argument logical?

- What are the qualities that make an argument illogical? Define what a logical fallacy is, and give some examples from the text. How do these fallacies connect to issues of rhetoric and ideology discussed previously in the chapter?

- Describe Burke’s theory of the “comic corrective.” What does that mean? How can it be used to raise your consciousness regarding the ideologies that are embedded in language and to inform your own response?

Sources

Berlin, James. “Rhetoric and Ideology in the Writing Classroom.” College English, vol. 50, no. 5, Sept. 1988, pp. 477–494, https://www.jstor.org/stable/377477.

Brown, Nicole. “Fallacy Examples.” YouTube, 14 July 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c5QdzqbCxgI.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. University of Berkeley Press: Berkley, 1945.

———. Attitudes Toward History. Third ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

———. Permanence and Change. New Republic: New York, 1935.

———. The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action. Vintage Books, New York, 1957.

Chaplain, Jessica Lauren. “No Laughing Matter: Revisiting Kenneth Burke’s Comic Approach to Criticism.” 2018. Appalachian State University, Honors Thesis. http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/f/Chaplain_Jessica_2018_Honors%20Thesis.pdf.

Giroux, Henry A. “The Crisis of Public Values in the Age of the New Media.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 28, no. 1, Mar. 2011, pp. 8–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2011.544618.

Hollihan, Thomas A., and James F. Klumpp. “Rhetorical Criticism as Moral Action Revisited: Moral and Rhetorical Imperatives in a Nation Trumped.” Western Journal of Communication, vol. 84, no. 3, 2020, pp. 332–348, https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2019.1704856.

“Ideology.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ideology#:~:text=plural%20ideologies,an%20individual%2C%20group%2C%20or%20culture.

Jørgensen, Frederik, et al. “Pandemic Fatigue Fueled Political Discontent During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” PNAS.org, 21 Nov. 2022, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2201266119.

Klumpp, James F., and Thomas A. Hollihan. “Rhetorical Criticism as Moral Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, no. 75, 1989, pp. 84–97.

LogicalFallacies.org. “Logical Fallacies.” Logicalfallacies.org, 2023, https://www.logicalfallacies.org/.

McGee, Michael Calvin. “The ‘Ideograph’: A Link Between Rhetoric and Ideology.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 66, no 1, 1980, pp. 1–16.

Miller, Chris, and Mia Poston. Exploring Communication in the Real World. Pressbooks.pub, 2020, https://cod.pressbooks.pub/communication/.

Pew Research Center. “Newspapers Fact Sheet.” PewResearch.org, 29 June 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/newspapers/.

Pimpare, Stephen. Politics for Social Workers: A Practical Guide to Effecting Change. Columbia University Press: New York, 2022.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. “Logical Fallacies.” Purdue.edu, n.d., https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/logic_in_argumentative_writing/fallacies.html.

Shearer, Elisa, and Katerina Eva Matsa. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2018.” PewResearch.org, 10 Sept. 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/.

Wander, Philip. “The Third Persona: An Ideological Turn in Rhetorical Theory.” Central States Speech Journal, vol. 35, no. 4, 1984, 197–216, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10510978409368190.

Xenos, Michael A., et al. “News Media Use and the Informed Public in the Digital Age.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 12, 2018, pp. 706–724.