1 Introduction

We’ll begin our exploration into writing for digital media with a fundamental premise that is both obvious and profound: Digital media is ubiquitous. Something that is ubiquitous is everywhere, all the time. Constant. Its prevalence in our lives has deep and enduring consequences, though it’s easy to become desensitized and overlook what those consequences might be. Our devices—our cell phones, smart watches, digital assistants (e.g., Echo Dots), laptops, iPads, smart TVs—are ubiquitous. For many of us, there isn’t a single moment of the day when our cell phone isn’t within arm’s reach so that we can quickly, if not compulsively, check our email, respond to a text message, scroll through social media, read the latest news updates, and so on.

Certainly, we are in the digital age. Reports vary depending on demographics, but many studies, including this one from Forbes, estimate that the average American spends nearly seven hours a day on some form of digital media (Koetsier, “Global”). This Forbes article describes our usage as “consumption,” which underscores the idea that we are perpetually compelled to engage in digital spaces and that we internalize those digital interactions as we form ideas about what is valuable or normal or true. So much of what we know about the world, from history to current events to every other subject imaginable, comes from the internet in some form. It not only provides information that helps shape our worldviews, beliefs, and identities, but it mediates most of our communication with other people, and it facilitates many of our daily activities, from ordering food to paying bills to finding the fastest route to our next destination. The word “consumption” also highlights the commercial aspect of digital media. Not only is digital content a commodity, but users themselves have become commodities as organizations compete for more views, likes, shares, click-throughs, and subscribers.

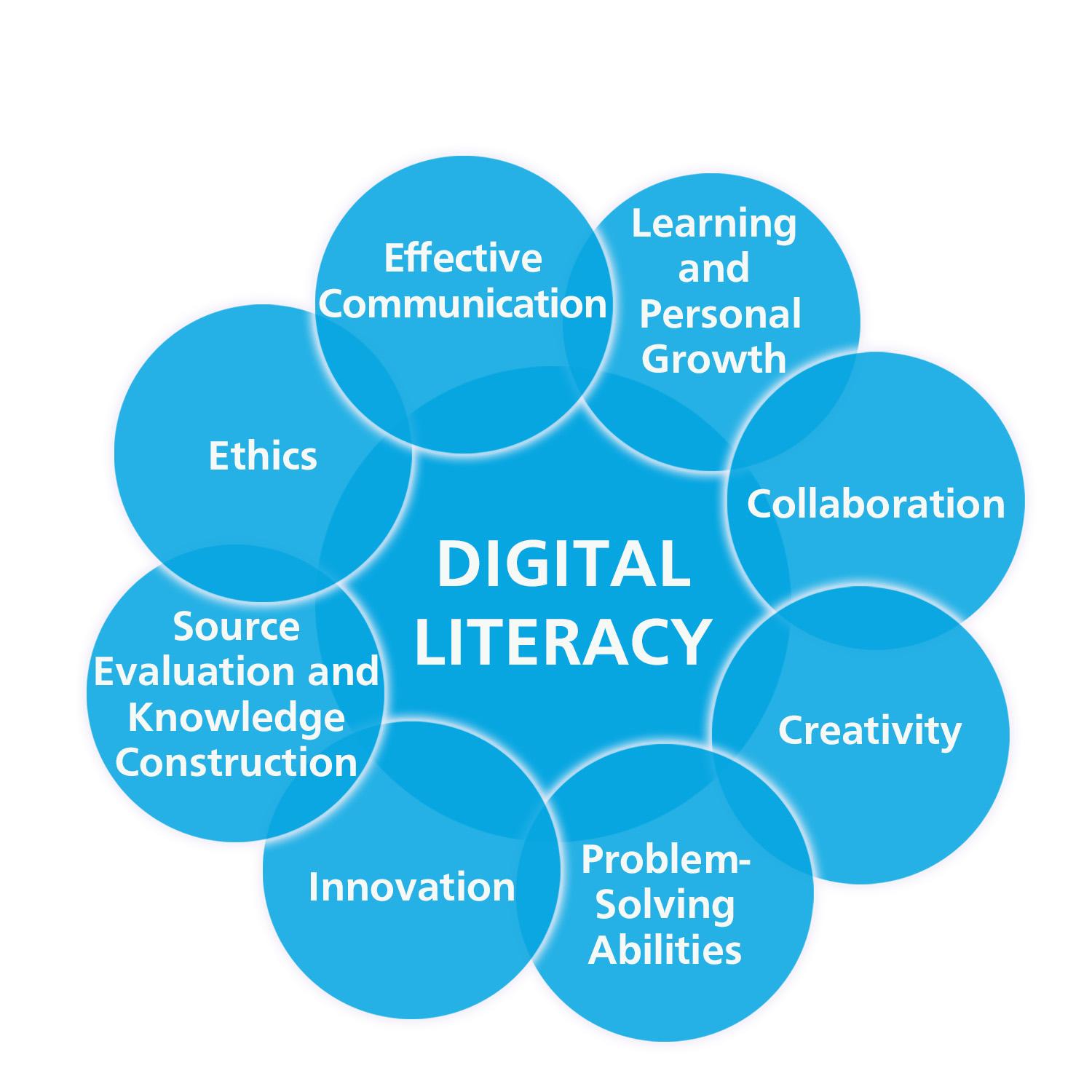

It’s no wonder that digital literacy has become such an important topic. In this book, digital literacy is defined as the ability to engage with digital spaces in meaningful, productive, and ethical ways to achieve personal, professional, or civic goals. It includes the strategies we use to find and evaluate information. It also includes our ability to share information and respond to others thoughtfully, strategically, and respectfully. In other words, digital literacy is more than knowing how. Yes, it’s important to know how to publish a website or how to create a social media post. However, it’s equally important to know why you are making certain choices and to what effect. Of particular importance are the ethical consequences of those choices. While many digital writers and designers leverage their rhetorical skills effectively in order to manipulate, dismiss, confuse, and control their audience, this textbook emphasizes digital literacy as an opportunity to develop a deeper awareness of complex power structures and social injustices that are often ignored and to challenge the status quo.

The most recent student learning standards published by the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) articulate the goals of digital literacy quite well. In acknowledging how important it is to prepare students “to thrive in a constantly evolving technological landscape,” ISTE identifies seven core objectives:

- Empowered Learner: Students leverage technology to take an active role in choosing, achieving, and demonstrating competency in their learning goals.

- Digital Citizen: Students recognize the rights; responsibilities; and opportunities of living, learning, and working in an interconnected digital world, and they act and model in ways that are safe, legal, and ethical.

- Knowledge Constructor: Students critically curate a variety of resources using digital tools to construct knowledge, produce creative artifacts, and make meaningful learning experiences for themselves and others.

- Innovative Designer: Students use a variety of technologies within a design process to identify and solve problems by creating new, useful, or imaginative solutions.

- Computational Thinker: Students develop and employ strategies for understanding and solving problems in ways that leverage the power of technological methods to develop and test solutions.

- Creative Communicator: Students communicate clearly and express themselves creatively for a variety of purposes using the platforms, tools, styles, formats, and digital media appropriate to their goals.

- Global Collaborator: Students use digital tools to broaden their perspectives and enrich their learning by collaborating with others and working effectively in teams locally and globally. (International Society for Technology in Education)

These standards underscore the deep critical thinking, developed from a strong sense of social ethics and personal values, that true digital literacy entails. And these skills have never been so important. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, everything shifted to the digital realm—classes, jobs, church attendance, doctor appointments, grocery shopping, conversations with family and friends. Digital media became our lifeline to the outside world and helped us maintain some sense of normalcy. Social media platforms exploded with chatter from people who were desperate to make connections with other people and to gain perspective on the ongoing crisis. While some of these interactions were positive, strengthening a sense of community and belonging, many were not. Fueled by the political and financial agendas of powerful media and commercial organizations, confusion, misinformation, conflict, and ultimately division have permeated social media. So many posts are hateful. So many people are unwilling (unable?) to listen to perspectives different from their own. Way too many people automatically accept or reject information that either coincides with or contradicts what they already believe—what they want to believe.

Recently, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, wrote an open letter about the “sources of dysfunction” on the web. He says, “The fight for the web is one of the most important causes of our time,” advocating for the need to protect human rights, equal access, and the open marketplace of ideas and social progress that the web was designed to provide. It follows, then, that true digital literacy is about much more than scrolling, surfing, liking, posting selfies, gaining followers, influencing buying habits, and spreading your opinions with the intent to shut other people down. It’s also not about being as active as possible on as many platforms as possible. In fact, given the ubiquitous nature of digital media, intentionality and selectivity are crucial. True digital literacy is about meaningful and thoughtful engagement that has a positive impact on you as well as the communities of which you are a part.

Writing for Digital Media was written with these lofty ideals in mind. This first chapter focuses on the historical shift from legacy media to digital media, which gave rise to active participation and personalization by and for everyday citizens, who experienced significantly more control over their media experiences. Even more significant were the fundamental changes to communication patterns and social interactions. The second part of the chapter sets up the remainder of the textbook by describing the overall framework of the remaining chapters and how that framework relates to the definition of digital literacy discussed above.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the history of digital media and how it quickly evolved to transform our daily lives.

- Compare the original intent of the World Wide Web to the current reality of privatization and commercial enterprise.

- Consider the trade-offs as technologies have developed to afford greater access to and participation in a growing marketplace of ideas.

- Recognize the ways that powerful organizations have sought to control the flow of public information throughout history.

- Compare the differences in audience engagement between traditional media and digital media.

- Understand the organizational structure of the textbook and how different forms of literacy create a more holistic and flexible approach to digital writing.

The History of Digital Media

A brief history lesson is in order to contextualize our digital media use and the opportunities it affords. It’s actually a pretty short history given that the World Wide Web, which precipitated the mass adoption of digital media, is little more than 30 years old. On the other hand, in that short period of time, it has grown at an astronomical rate. According to Broadband Search, 5.25 billion people worldwide are currently connected to the internet, which represents 66.2% of the world’s population, and that number grows by the millions every year. In fact, the percentage of online users grew by 1,355% from 2020 to 2022. The site goes on with statistics about the millions of people who are active on social media, who write blogs, who utilize video streaming services, and who shop online. Perhaps even more significant is the sharp increase in remote working (Saad and Wigert) and remote learning (National Center for Education Statistics) in the U.S., along with the recent spike in e–commerce that continues to claim a higher percentage of our total retail sales every year (U.S. Department of Commerce).

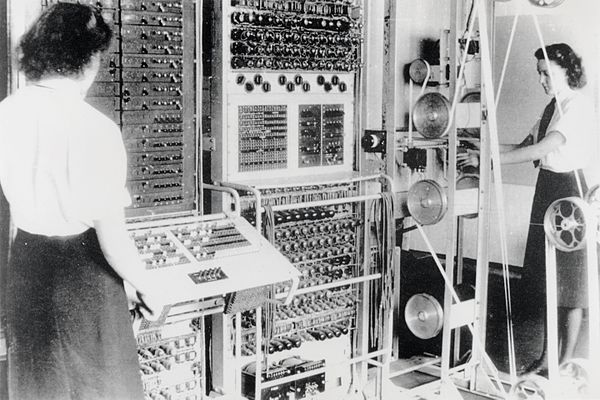

It’s not an exaggeration by any stretch to say that digital media is a central component of our daily lives—or that most of the world would come to a grinding halt without it. Given this reality, it’s even more startling to consider digital media’s humble beginning. Development happened in stages, beginning with the invention of Colossus in 1944 (National Museum of Computing, “Colossus”). As its name suggests, Colossus was enormous, approximately the size of a living room and weighing more than five tons. And in contrast to the multifunctional, general-purpose devices we have today, Colossus had one job: to decode encrypted messages between Hitler and his troops during World War II. It was also incredibly slow: 5,000 characters per second compared with modern computers that process billions of instructions per second (Copeland).

What made Colossus digital was the way that it processed and stored information using Boolean logic. Though it didn’t have software to direct its operations like today’s digital devices, it did have a series of switches and plugs that worked much the same way to create binary values (positive and nonpositive) that told it what to do and could be expanded to create complex functions. Of course, in this early stage as digital technology became faster and held more memory capacity, its use was strictly limited to governmental purposes. In fact, the very existence of Colossus was kept secret until 1975 so that it could remain a secret weapon of the military (National Museum of Computing, “Colossus Decrypts”).

The internet was also developed as a tool for the U.S. military, this time as a mechanism of defense during the Cold War (History.com). Out of growing concerns for what might happen if the Soviet Union figured out how to shut down our telephone system—the crux of long-distance communication at the time—ARPAnet was created in 1965 to enable government computers to share information. Developed by electrical engineers and mathematicians at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), ARPAnet was special because it used “packet switching” to break down information into chunks of data that would have unique routing paths to their destination. This made it much less vulnerable to interception or enemy attack. However, development was fairly slow. It wasn’t until 1969 that the first message was sent from one (gigantic) computer to another. The word “login” was sent as a test, but only “lo” made it through before the system crashed. Eventually, electronic mail became one of the most important functions of ARPAnet.

Another challenge was figuring out how to grow the network. In fact, there wasn’t one singular network. ARPAnet, with its handful of computers, became one among several other mini-networks. As the number of packet-switching networks with differing configurations grew and tried to connect to one another, it became increasingly difficult to integrate them into one seamless communication system. As a result, Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) was developed in the late 1970s by Vinton Cerf and Robert Kahn, often referred to as the “fathers of the internet” (Nott). TCP/IP was—and still is—the fundamental language that allowed networks with different configurations to communicate, effectively bringing everything together under the umbrella of one global network.

Despite its growing capabilities, the use of the internet was restricted to government officials, military personnel, and university professors throughout the 1980s. The National Science Foundation developed the Computer Science Network (CSNET) for university computer scientists across the country, and as the need for faster communication amid increasing traffic arose, NSFNET was developed in 1986 as the “backbone” of an internet infrastructure that would later support widespread use (National Science Foundation, “A Brief History”). The most popular online communications at the time were email, discussion groups (1979) (Encyclopedia Britannica, “USENET”), Internet Relay Chat (IRC; 1988) (Dominquez), and text-based games (i.e., Multi-User Dungeons [MUDs] and MUD Object-Oriented games [MOOs]).

In other words, functionality as well as access was still fairly limited throughout the 1980s, but all of that changed in 1991 with the advent of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee. The web allowed use of the internet to go beyond simply sending information from one computer to another. Users could now post and retrieve information that was intended for mass consumption across the web. The web became a mechanism for sharing information among all participants, and with the release of the first popular web browser (Mosaic, later called Netscape) in 1993, the web became accessible for public use (Andreessen). From that moment on, the number of participants in as well as the varying uses of the internet grew exponentially, which precipitated the rapid advancement of digital media devices and platforms that have transformed our everyday lives.

Commercialization of the Internet

If the development of the internet was central to the advancement of digital media, so too was the commercialization of the internet as companies found ways to capitalize on its capabilities for financial gain. This continues to be an issue of debate as large corporations continually pioneer technological advances in order to privatize their services and extend their commercial reach (Goodman). On the one hand, these commercial firms paved the way for mass adoption of the internet and the digital innovations that are fundamental to our personal and professional activities. But on the other hand, the increasing commercialization of the internet has shifted its underlying purpose—from information sharing and collaboration to targeted marketing, clickbait, and commodification of all goods and services. Users themselves have become commodities in the fight to capture attention and increase CTRs (click-through rates) (Hess).

When the National Science Foundation (NSF) developed NSFNET, its purpose was to further the advancement of education and research, not commercial enterprise (Legal Information Institute). In fact, the use of NSFNET for commercial purposes was banned. It was free for academic institutions to share and access information. The NSF also paid for domain names so that it was free for users to register a website. But as the network grew, extending to university libraries, public schools, small-town libraries, and eventually individual households, it became more difficult for the NSF to keep up with the growing demand, and private companies battled for control. Commercialization occurred in stages throughout the 1990s (National Science Foundation, “A Brief History”), which was marked by several pivotal changes:

- “The World” emerged as the first commercial internet service provider (ISP; 1989). Though its dial-up service was incredibly slow by today’s standards, the number of customers multiplied (Schuster).

- The NSF lifted the ban that prevented the commercial use of the internet (1991). Private industries could now use the internet for business and commercial purposes. More commercial ISPs became available, including CompuServe, The Source, and America Online (AOL).

- Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web (1991), which is now commonly known as Web 1.0 because it focused on providing information to users, but pages were static and didn’t allow for much user participation. He later advocated for widespread public use of the web by relinquishing proprietary rights to the code he created (1993) (World Wide Web Foundation). The World Wide Web was the first internet browser, making it possible to search for specific information. Other browsers, including Netscape Navigator and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, improved the internet’s functionality and prompted increased growth.

- The NSF solicited bids from private companies to manage nonmilitary domain registrations (1993). Network Solutions, Inc. was awarded the five-year contract, and under their management, the number of commercial domains grew rapidly, increasing from 7,500 domain names in 1993 to more than two million at the end of their contract in 1998. In 1995, the NSF began charging a fee for domain registration.

- NSFNET was decommissioned (1995), which allowed for greater public access as private companies made their internet services available (National Science Foundation, “The Internet”). The NSF officially and completely discontinued any direct control it had over the management of the internet (1998).

- Technological advances throughout the 1990s and early 2000s made the internet much faster and more versatile. Broadband services included DSL (Digital Subscriber Line), cable internet, and fiber optic lines, which transferred increasing amounts of data that could travel around the world at the speed of light (Encyclopedia Britannica, “DSL”).

- Google began in 1998 as a search engine and soon offered other services, including email, analytical tools, maps, advertising programs, and a mobile operating system (Google). Of particular importance was the algorithm Google used to rank web pages in order of relevance and credibility (Star). Soon, companies were paying for ads and also “optimizing” their websites to ensure more prominent placement.

- Mobile internet technology became more advanced with the introduction of the 2G cellular network (1991), which allowed users to access media content and communicate via text message (SMS) and multimedia message (MMS). The iPhone 2G was released in 2007, but it was quickly replaced as 3G, 4G, and 5G technology developed, offering higher speeds, more data transfer, higher-quality streaming, and more functionality (Eadicicco).

- Web 2.0 was introduced (2004) with a focus on user-generated content and increased interaction among users (Encyclopedia Britannica, “Web 2.0”). Social media platforms like MySpace (launched in 2003), Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), and X (2006; formerly known as Twitter) became increasingly popular. However, increased user participation also resulted in more marketing opportunities as well as analytical features that allowed companies to collect information about specific behaviors and buying patterns.

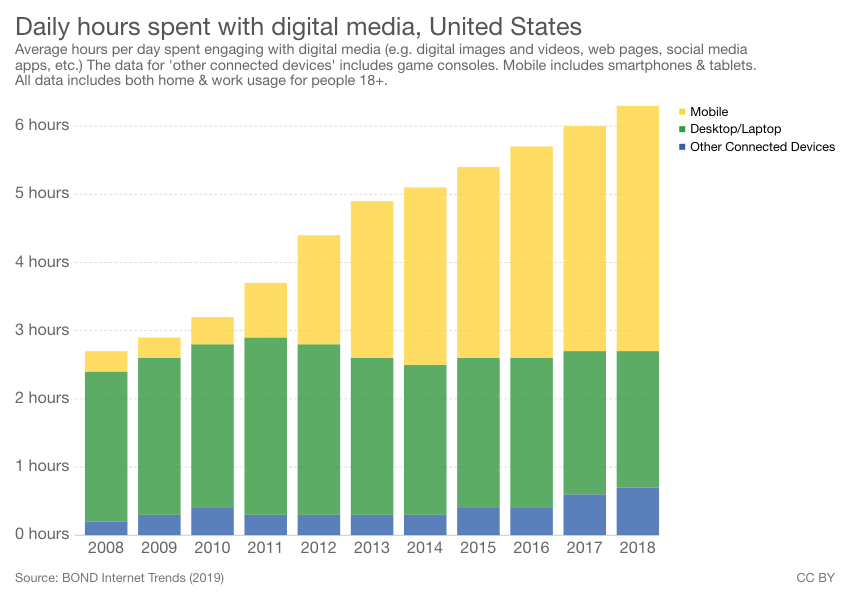

Of course, that was just the beginning. In the last two decades, advancing technologies have made it possible to capture people’s attention at all times of the day and night, even as they move from place to place. A recent article from the Pew Research Center reports that 85% of Americans own a smartphone, a number that is up significantly from just 35% in 2011 (“Mobile Fact Sheet”). What’s more, people’s digital media usage has more than doubled, as evidenced by the chart below by Our World In Data. While people averaged less than three hours a day of digital media usage in 2008, they averaged well above six hours a day by 2018. That number rose above seven hours in 2022, according to Insider Intelligence (Cramer-Flood). More time spent on digital media means more opportunities for companies to advertise to potential consumers, which is why they put so much money into targeted marketing, omnichannel messaging, optimizing their websites, sending push notifications, and tracking users’ online behaviors and buying habits. They want to tap into the digital economy, which rose to a record-breaking $1.09 trillion in 2022 (Koetsier, “E-Commerce Retail”).

As companies increasingly used digital spaces to compete for people’s attention (and money), several trends emerged in the 2010s:

- Social media marketing. While just 5% of the adult population used social media in 2005, today more than 72% use some sort of social media (Pew Research Center, “Social Media”). In fact, about half of Americans use social media as their primary source of news information (Pew Research Center, “News Consumption”). Social media has also become an important tool for social activists (consider the Arab Spring [Hempel] or the 2019 protests in Hong Kong [Shao], for instance), humanitarian campaigns (e.g., the war in Ukraine [Spotlite]), and political campaigns (Wharton). Most prominent are businesses that use social media to interact with customers and advertise their latest products and services. According to a recent Forbes article, 77% of small businesses use social media regularly (Wong). Many companies use social media as their primary method of marketing, believing that it is the most effective way to reach their target audience (Cision).

- Influencers. Increasingly, businesses hire influencers to engage with potential customers because they already have a large number of social media followers and can leverage those connections to influence people’s buying habits. They test products and make recommendations, and while it might seem that these people have the consumer’s best interest at heart, the reality is sometimes a little different. “On the consumer side, the relationship between influencers and consumers is based on perceived closeness, authenticity, and trust,” according to Michaelsen et al., who go on to discuss the potentially negative impact of influencers on consumers, particularly more vulnerable populations such as children or consumers with low education. Their study found several negative characteristics of influencer marketing, including “lack of transparency and unclear disclosure, lack of separation between advertising and content misleading messages, and targeting vulnerable consumer groups” (Michaelsen et al. 10). While in some instances it’s considered unlawful for an influencer to endorse specific products without fully disclosing that they are being paid to do so—see the anti-touting provision (Section 17b) of the Securities Act (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “Securities”) and the recent charges against Kim Kardashian for using social media to endorse an investment opportunity (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “SEC Charges”)—influencers often don’t fully disclose their financial incentives.

- App culture and push notifications. You’re probably familiar with Apple’s catchphrase “There’s an app for that,” which debuted in a 2009 commercial advertising iPhone’s latest capabilities. Since then, app culture has exploded with entertainment, educational, and lifestyle applications, which provide quick and easy access to a variety of activities and information. They also allow for notifications to be pushed out to users, often prompting them to take action to open the application, visit the website, or take advantage of a new product or promotional opportunity. While the Pew Research Center reported in 2010 that fewer than half (43%) of cell phone users had apps on their phones (“The Rise of Apps Culture”), more recent data suggest that the average cell phone user has 40 apps installed on their phone and consistently accesses 18 of those apps (Kataria).

- Gig economy. With more websites, applications, and channels of communication, more businesses and freelancers have emerged in the “gig economy,” which relies mostly on short-term and contract employees who value their independence to accept or decline jobs as they see fit but who also must “produce or perish” (Petriglieri et al.). In 2015, Hillary Clinton forecasted the “exciting” economic opportunities and new innovations that stemmed from the gig economy (qtd. in Sundararajan), but some people point out that on-demand businesses like Uber, Airbnb, Etsy, and TaskRabbit are the true beneficiaries, making money off the labor exchange without having to provide consistent salaries or benefits: “There’s a risk we might devolve into a society in which the on-demand many end up serving the privileged few” (Sundararajan).

- IoT and big data. The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to the emergence of objects and systems that use wireless internet connections to send and receive data, often through the convenience of your phone (Fruhlinger). Think about all of the devices that have emerged in the last 10 years with the word “smart” in front of them—smart watches, smart TVs, smart refrigerators, smart door locks, smart thermostats, smart vacuums. A 2019 article in Priceonomics put it like this:

The growth of Internet of Things in terms of number of devices, revenue generated, and data produced has been stunning, but most predictions expect that growth to accelerate. The number of connected devices is expected to grow to 50 billion in 2020 (from 8.7 billion in 2012) and the annual revenue from IoT sales is forecast to hit $1.6 trillion by 2025 (from just $200 billion today). (Team Recurrency)

The article goes on to discuss the astronomical amount of data (otherwise known as big data) collected by these devices—upward of 4.4 zettabytes in 2020—which is used to track user behaviors and trends, understand consumer needs, make product upgrades, and essentially market more relevant products and services to customers. While this might seem like a benefit in many ways, there are concerns about how closely IoT devices allow large corporations and government entities to track people’s behavior. Josh Fruhlinger used the recent example of a map released by X-Mode (O’Sullivan) in 2020 that was designed to track the location of spring breakers as they left Fort Lauderdale. The purpose was to predict the spread of COVID-19, but it also demonstrated “just how closely IoT devices can track us” (Fruhlinger).

- User tracking. While we’re on the topic of user tracking, it’s another trend that emerged in the 2010s. Although Urchin was an analytics business that formed in the early days of the web (1995), it wasn’t bought out by Google to become Google Analytics until 2005, and there weren’t sophisticated tracking tools until 2014, when Google released Universal Analytics, which could track individual users across multiple devices and platforms (Visualwebz). Once more, the benefit is a more enjoyable user experience, though there are significant concerns about user tracking, data security, and the use of data to not only predict but also compel purchasing decisions (Zuboff).

- Artificial intelligence. You might be surprised to learn that artificial intelligence (AI) dates back to the 1950s as technology advanced allowing computers to more easily store information and use algorithms to complete tasks (Anyoha). However, it wasn’t until the 2010s that AI became commonplace through Alexa devices, GPS, talk-to-text applications, and so on. Most of us encounter AI devices multiple times throughout the day, and our use of those devices (and the data collected as a result) is used in turn to train the AI to become smarter and better at what it does. Many IoT devices use AI to simulate human intelligence and complete tasks. This is called “machine learning,” which David Grossman describes as “exciting and somewhat terrifying” given this potential for complex functionality. Peskoe-Yang explains that as we use AI in our daily lives, “AI is tasked not only with finding the answers to questions about data sets, but with finding the questions themselves; successful deep learning applications require vast amounts of data and the time and computational power to self-test over and over again.” While recent AI technologies like ChatGPT have created some exciting opportunities, there are concerns about the performance accuracy of ChatGPT (Chen et al.) and the ethical implications of relying on AI devices fueled by biased algorithms (UNESCO).

- Scams and security breaches. Let’s not forget about those scammers, hackers, and phishers who are also hoping to profit from advanced technologies and all the user data out there. While viruses and other types of malware became a concern in the early 2000s, cybercrime became much more profound and sophisticated in the 2010s as criminals developed “multi-vector attacks and social engineering” (Chadd). Expensive data breaches have affected not only large corporations and government entities but also individual users, which is why cybersecurity has become such an important (and lucrative) field (Fortune Business Insights).

We now live in a world where the quality of life seems to hinge on the speed of our internet connection as billions of people spend hours every day streaming their favorite shows, scrolling through social media, and browsing Amazon merchandise. User activities are tracked and assessed for the purposes of providing more targeted, personalized ads and creating a more positive user experience that perpetuates increasing dependence on digital technologies. In so many ways, the commercialization of the internet ushered in the digital age that has provided tangible benefits in communication, entertainment, collaboration, access to information, and countless daily conveniences. But at what cost? According to Business Insider, 90% of the information we consume is controlled by a handful of powerful corporations (Lutz). Increased surveillance, misuse of personal data, cyberbullying, addiction, burnout, and self-indulgence are equally prevalent. These are issues that we will examine more closely in the first section of the textbook, which focuses on writing and digital media from a critical perspective.

Acronyms from this Chapter

|

Acronym |

Full Name |

Description |

|

ARPAnet |

Advanced Research Projects Agency Network |

The first public packet-switched network, created by DARPA in 1965. |

|

DARPA |

Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency |

Research agency that is part of the United States Department of Defense. It developed ARPAnet. |

|

CSNET |

Computer Science Network |

Network developed in the 1980s by the Computer Science Network for university computer scientists across the country. |

|

CTR |

click-through rate |

The number of times an ad receives a “click” to see more information divided by the number of views. |

|

DSL |

digital subscriber line |

A collection of technologies that transmit digital data over the telephone line. |

|

IoT |

Internet of Things |

The network of devices that connect to the internet and can exchange data with other devices and systems over the internet. |

|

IRC |

Internet Relay Chat |

Text-based chat system for instant messaging. |

|

ISP |

internet service provider |

Company that provides internet access. |

|

ISTE |

International Society for Technology in Education |

“A passionate community of global educators who believe in the power of technology to transform teaching and learning” (ISTE, “About”). |

|

MOO |

MUD Object-Oriented |

Online virtual reality system in which players are connected at the same time. |

|

MUD |

Multi-User Dungeon |

A multiplayer online space. |

|

NSF |

National Science Foundation |

A government agency that supports research and education in science and engineering. |

|

NSFNET |

National Science Foundation Network |

Network developed by the National Science Foundation in 1986 as the “backbone” of an internet infrastructure. |

|

TCP/IP |

Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol |

A standardized set of rules for delivering data across a digital network. |

The Shift to Participatory Media

One last historical shift is especially relevant to the scope of this book: that from traditional media, in which audiences took a passive role in their media consumption, to digital media, in which users are actively searching for the information they want and contributing to the pool of information with their own posts, shares, and comments. While this is such common practice in our current daily lives that it hardly seems remarkable, it’s particularly significant when we consider the larger historical context of censorship, in which institutions with centralized authority—such as the Catholic church in the fourteenth century (Mark) or the American government during the colonial period (Lokey)—controlled the flow of information to the masses. In fact, the invention of the Gutenberg Press in 1445 and the subsequent increase in literacy rates (Ormond) was considered a threat to the centralized authority of the church because people had more direct access to information and could read and interpret that information for themselves—and form their own opinions. You probably already know that literacy is a powerful tool for personal and intellectual growth, independence, and expression, which is why marginalized groups have historically been discouraged from reading (e.g., anti–literacy laws for slaves) and especially from writing about their own experiences and perspectives (Maddox; Monaghan).

We could talk endlessly about how information has been distributed throughout history—penny presses and wire services, for instance (Illinois University Library), as well as more secretive and subversive methods (Coleman; Harriet Tubman Historical Society)—and the social effect this information had, such as yellow journalism (Ferguson III), muckraking (Schiffrin), civic unrest (Green), and social movements (Coleman). What seems most important is that the flow of information had a profound effect on people’s thought patterns and worldviews, and the struggle to control that flow of information escalated as more people—usually professional writers—were able to publish their ideas. Further, as traditional media expanded to include radio and television, the amount of information people had access to grew exponentially. Suddenly, people could tune in from the comfort of their living rooms to watch their favorite show, learn about news events across the globe, and even hear directly from the president himself. However, it was a one-way line of communication. People themselves had very little control over the content that was widely dispersed for public consumption. They could tune in or not tune in, read the morning paper or not, but it made no difference in the content itself, and to miss out on the latest news would mean falling behind in public affairs and being left out of the social discourse.

Importantly, the limitations of traditional media stemmed from the technology that was available. Traditional media, also known as legacy media, included newspapers, books, magazines, radio, and television—all of which were defined by key characteristics:

- Intended for a mass audience. The same information was available to everyone, without distinction, and people couldn’t pick and choose the type of information that seemed most relevant or interesting to them.

- Limited space. A television or radio broadcast could only fit so much information into a 30-minute segment. Newspapers, books, and magazines were likewise limited by the amount of space available on the page.

- Linear format. No matter the publication, there was always a clear beginning and a clear ending, and people consumed the information in straightforward, chronological order.

- Fixed. Once something was published, it was permanently set on the page or the film. It couldn’t be revised.

- Noninteractive. Audience members could only receive information. There was no way to participate in the conversation.

- Limited access. Because of the limitations already listed, the role of producing information was reserved for professionals in the industry—journalists, news anchors, actors/actresses, novelists. There was very little opportunity for everyday people to have their voices heard on a mass scale.

Obviously, digital media ushered in a new era that dramatically altered the relationship between everyday citizens and the flow of information. The emergence of the World Wide Web, cable television, social media, and an onslaught of digital devices that make it possible for people to easily and quickly access the internet from almost anywhere has shifted our role from passive to active. People can actively search for the type of information they are looking for and cultivate an online repertoire of resources that fit their interests and perspectives. They can also contribute to the vast body of information that is available on the internet—without needing special credentials or authorization. In direct contrast to the limitations of traditional media, digital media is defined by qualities that invite user participation:

- Personalized based on online habits, interests, and the ability to customize your news feed.

- Unlimited space. The information available online is immeasurable and continues to expand.

- Nonlinear formatting as information is increasingly hyperlinked and put into chunks that can be viewed in any order.

- Fluid. Information posted to the internet can easily be updated.

- Interactive as people like, share, and comment on the information that is posted and can easily post their own information.

In so many ways, we have come full circle from the era of the Gutenberg Press. As new technologies emerge, they have completely revolutionized the way that we access information, which in turn has a deep and pervasive effect on our ways of thinking, being, and interacting with the world. Once again, as more voices emerge to share new ideas and perspectives, we often sacrifice quality for quantity and must question the credibility of information that is available. And once more, despite the purpose of the World Wide Web to be a marketplace for ideas and social progress, we must recognize the continuing (though certainly evolving) epic battle to control the flow of information and thought patterns for self-serving purposes.

Activity 1.1

Review the history of digital media as outlined in this chapter and make a list of key dates and events that you think are most important in understanding our current digital media practices. You might also add events to your list by reading sources that are linked in the text or by conducting your own research.

Once you’ve created your list, create some sort of visual representation of the events you’ve selected (a timeline, for instance, or a web). You can draw your visual representation. Or, ideally, you can use Canva, Photoshop, or some other design application of your choice to create a graphic that is informative, easy to understand, and visually appealing.

You will share your visual and explain the choices you made.

Looking Ahead: The Framework for This Textbook

At first glance, the topic of digital writing seems fairly straightforward. In fact, it’s true in some ways that digital writing is similar to traditional print media and that some writing skills and strategies will be similar. However, digital writing is also different from traditional forms of writing in fundamental ways and, therefore, often requires different strategies and skills, which we’ll explore in-depth throughout this textbook. However, as discussed in the beginning of this chapter, the goal of this textbook is about more than how to apply certain strategies in digital spaces, but also why and to what effect. It’s about having a deeper theoretical and ethical understanding of the communication choices you make, which will afford you greater intentionality and precision, not just in the things you write but in your interactions with other people and in your own literacy practices. To that end, the textbook casts a wider net to include both practice and theory, challenging readers to think critically about the opportunities that digital media affords as well as the challenges it presents to mental health, civil discourse, social justice, privacy, and so on.

The book is divided into three sections, mirroring the organizational structure of Stuart Selber’s Multiliteracies for a Digital Age, which focuses more broadly on computer literacy and targets writing and communication teachers in higher education. However, Selber emphasizes the need to extend conversations about digital literacy far beyond a simple and prescriptive how-to guide. He writes, “It is clear…that computer literacy programs can take a rather monolithic and one-dimensional approach, ignoring the fact that computer technologies are embedded in a wide range of constitutive contexts, as well as entangled in value systems” (22). In other words, an effective educational approach to digital literacy provides critical-thinking tools that can be applied to different situations and guide a more informed decision-making process based on the context at hand. In that spirit, this textbook offers a top-down approach to writing for digital media by examining three different literacies:

- Critical literacy, which challenges readers to think deeply about the affordances and constraints of digital media, their own practices, and the social ramifications of communication that takes place on digital platforms. In this first section, the word “critical” has two meanings. It relates to critical thinking about relevant theories that can be used as lenses to examine social norms and personal habits of digital media use from a variety of perspectives. It also relates to critical theory, which focuses on power structures and cultural biases that marginalize certain groups of people while privileging others. The chapters in this first section are intended to provide deeper insights and new ways of thinking about digital media use that will inform the rest of the book.

- Rhetorical literacy, which situates digital media as a communication tool that mediates between writers and their audiences, helping them to convey important ideas and perspectives as clearly as possible. All communication is about forging an understanding. Rhetoric is the study of how language (both verbal and nonverbal) is used in that endeavor, paying special attention to how a message is crafted by a speaker to engage a specific audience to fulfill key purpose(s) in a particular situation. This section of the book focuses on rhetorical considerations and strategies that make a message successful, particularly given the range of digital platforms and tools that are available.

- Functional literacy, which is the nuts and bolts of digital writing, providing guidelines, best practices, and design strategies for a variety of genres. The last section also gives important information about content strategy, search engine optimization, copyright laws, accessibility considerations, and basic editing rules. In essence, this is the how-to part of the textbook that builds from the theoretical and rhetorical considerations of the previous sections.

If you are familiar with Selber’s work, you might notice that this organization of sections is different from his as he begins with functional and then moves on to critical and then rhetorical. This book begins with critical literacy (arguably the most complex and theoretical) followed by rhetorical literacy because having this type of deeper awareness and reflection should be foundational in guiding the specific writing choices you make, bringing certain issues into focus and informing strategies that will align with your values and resonate more deeply with your audience.

Obviously, digital media is always evolving. The historical shifts outlined in this first chapter are evidence of how quickly digital media has emerged to transform our daily lives. And there’s no telling what digital innovations will arise in the years to come. The goal of this textbook is to provide a foundation of intellectual processes and rhetorical considerations that are flexible and easily adapted to a variety of circumstances, so that as new technologies evolve, so will you.

Discussion Questions

- Reflect on your own digital media practices. What types of reading and writing do you do most often? How would your life be different without digital media?

- Review the list of learning standards published by the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). Can you come up with specific examples of each objective? How would you rank your own skills in each category?

- Summarize the primary concerns outlined by Tim Berners-Lee in his open letter. In your opinion, which ones seem the most detrimental? Why? Are there other concerns about the state of the World Wide Web that you would add to the list?

- What do you find most surprising about the history of digital media and the ways that technologies have evolved?

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the commercialization of the internet.

- Give some examples of how commercialization and privatization affect your own digital experiences.

- How are the social and intellectual effects of the printing press similar to those of digital media?

- How and why have powerful organizations throughout history controlled the flow of public information? What is your reaction to claims that powerful corporations control the vast majority of information available?

- Summarize the three types of literacies that form the textbook’s framework. Why is it beneficial to study digital writing using this top-down approach?

Sources

Anyoha, Rockwell. “The History of Artificial Intelligence.” SITNBoston, 2017, https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/history-artificial-intelligence/.

Andreessen, Marc. “Mosaic: The First Global Web Browser.” LivingInternet.com, 20 Feb. 1993, https://www.livinginternet.com/w/wi_mosaic.htm.

Apple. “iPhone 3G Commercial: ‘There’s an App for That’ 2009.” YouTube, 4 Feb. 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szrsfeyLzyg.

Berners-Lee, Tim. “30 Years On, What’s Next #ForTheWeb?” Web Foundation, 12 Mar. 2019, https://webfoundation.org/2019/03/web-birthday-30/.

BroadbandSearch. “Key Internet Statistics to Know in 2022 (Including Mobile).” Broadband Search, 2022, https://www.broadbandsearch.net/blog/internet-statistics.

Chadd, Katie. “The History of Cybercrime and Cybersecurity, 1940–2020.” Cybercrime Magazine, 30 Nov. 2020, https://cybersecurityventures.com/the-history-of-cybercrime-and-cybersecurity-1940-2020/.

Chen, Lingjao, et al. “How Is ChatGPT’s Behavior Changing over Time?” Arxiv.org, 1 Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.09009.

Cision. “Small Businesses Value Social Media over All Other Digital Marketing Channels.” Cision PR Newswire, 21 Mar. 2022.

Coleman, Colette. “How Literacy Became a Powerful Weapon in the Fight to End Slavery.” History.com, 11 July 2023, https://www.history.com/news/nat-turner-rebellion-literacy-slavery.

Copeland, B. J. “Colossus Computer.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Aug. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/technology/Colossus-computer.

Cramer-Flood, Ethan. “US Time Spent with Media Forecast 2023: A Slight Decline Overall, Even as CTV Time Surges, and Digital Video Finally Overtakes TV.” Business Insider, 11 July 2023, https://www.insiderintelligence.com/content/us-time-spent-with-media-forecast-2023.

Dominquez, Amanda. “Internet Relay Chat.” NYU.edu, n.d., https://kimon.hosting.nyu.edu/physical-electrical-digital/items/show/1363.

Eadicicco, Lisa. “This Is Why the iPhone Upended the Tech Industry.” Time, 29 June 2017, https://time.com/4837176/iphone-10th-anniversary/.

Encyclopedia Britannica. “DSL Networking Technology.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Nov. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/technology/DSL.

———. “USENET: Internet Discussion Network.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 May 2021, https://www.britannica.com/technology/USENET.

———. “Web 2.0 Internet.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Sept. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Web-20.

Ferguson III, Cleveland. “Yellow Journalism.” The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009, https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1253/yellow-journalism#:~:text=Yellow%20journalism%20usually%20refers%20to,unconventional%20techniques%20of%20their%20rival.

Fortune Business Insights. “Cybersecurity Market Size, Share, and Covid19 Impact Analysis…” Fortune Business Insights, n.d., https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/cyber-security-market-101165.

Fruhlinger, Josh. “What Is IoT? The Internet of Things Explained.” Network World, 7 Aug. 2022, https://www.networkworld.com/article/3207535/what-is-iot-the-internet-of-things-explained.html.

Goodman, Carly. “Commercialization Brought the Internet to the Masses. It Also Gave Us Spam.” Washington Post, 4 Aug. 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2017/08/04/commercialization-brought-the-internet-to-the-masses-it-also-gave-us-spam/.

Google. “From the Garage to the Googleplex.” Google, https://about.google/our-story/#:~:text=In%20August%201998%2C%20Sun%20co,was%20officially%20born.

Green, Adam. “Yellow Journalism: The ‘Fake News’ of the 19th Century.” The Public Domain Review, 21 Feb. 2017, https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/yellow-journalism-the-fake-news-of-the-19th-century.

Grossman, David. “How Machine Learning Lets Robots Teach Themselves.” Popular Mechanics, 19 Dec. 2017, https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/robots/a14457503/how-machine-learning-lets-robots-teach-themselves/.

Harriet Tubman Historical Society. “Songs of the Underground Railroad.” Harriet Tubman Historical Society, n.d., http://www.harriet-tubman.org/songs-of-the-underground-railroad/.

Hempel, Jessi. “Social Media Made the Arab Spring, But Couldn’t Save It.” Wired, 26 Jan. 2016, https://www.wired.com/2016/01/social-media-made-the-arab-spring-but-couldnt-save-it/.

Hess, Amanda. “How Privacy Became a Commodity for the Rich and Powerful.” New York Times, 9 May 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/09/magazine/how-privacy-became-a-commodity-for-the-rich-and-powerful.html.

History.com. “The Invention of the Internet.” History.com, 28 Oct. 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/invention-of-the-internet#:~:text=The%20internet%20got%20its%20start,share%20data%20with%20one%20another.

Illinois University Library. “American Newspapers, 1800–1860: City Newspapers.” Illinois University Library, https://www.library.illinois.edu/hpnl/tutorials/antebellum-newspapers-city/.

International Society for Technology in Education. “About.” ISTE.org, 2022, https://www.iste.org/about/about-iste.

———. “ISTE Standards: Students.” ISTE.org, 2022, https://www.iste.org/standards/iste-standards-for-students.

Kataria, Maitrik. “App Usage Statistics 2022 That’ll Surprise You (Updated).” Simform, 4 Jan. 2023, https://www.simform.com/blog/the-state-of-mobile-app-usage/.

Koetsier, John. “E-Commerce Retail Just Passed $1 Trillion for the First Time Ever.” Forbes, 29 Jan. 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2023/01/28/e-commerce-retail-just-passed-1-trillion-for-the-first-time-ever/?sh=bff541a36df2.

Koetsier, John. “Global Online Content Consumption Doubled in 2020.” Forbes, 26 Sept. 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/09/26/global-online-content-consumption-doubled-in-2020/?sh=d429c9e2fdeb.

Legal Information Institute. “42 U.S. Code § 1862—Functions.” Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1862.

Lokey, Fiona. “The History of Censorship in America.” M-A Chronicle, 5 Oct. 2016, https://machronicle.com/the-history-of-censorship-in-america/.

Louise, Nickie. “These 6 Corporations Control 90% of the Media Outlets in America: The Illusion of Choice and Objectivity.” Tech.com, 18 Sept. 2020, https://techstartups.com/2020/09/18/6-corporations-control-90-media-america-illusion-choice-objectivity-2020/.

Lutz, Ashley. “These 6 Corporations Control 90% of the Media in America.” Business Insider, 14 June 2012, https://www.businessinsider.com/these-6-corporations-control-90-of-the-media-in-america-2012-6.

Maddox, Carliss. “Literacy by Any Means Necessary: The History of Anti-Literacy Laws in the U.S.” Oakland Literacy Coalition, 12 Jan. 2022, https://oaklandliteracycoalition.org/literacy-by-any-means-necessary-the-history-of-anti-literacy-laws-in-the-u-s/#:~:text=Anti%2Dliteracy%20laws%20made%20it,color%20to%20read%20or%20write.

Mark, Joshua. “Index of Prohibited Books.” WorldHistory.org, 21 June 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2018/index-of-prohibited-books/.

Michaelsen, Frithjof, et al. “The Impact of Influencers on Advertising and Consumer Protection in the Single Market.” Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, Feb. 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/703350/IPOL_STU(2022)703350_EN.pdf.

Monaghan, E. Jennifer. “Reading for the Enslaved, Writing for the Free: Reflections on Liberty and Literacy.” James Russell Wiggins Lecture in the History of the Book in American Culture, Antiquarian Society, 6 Nov. 1998, https://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44525153.pdf.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Fast Facts: Distance Learning.” Institute of Educational Practices, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80.

National Museum of Computing. “Colossus.” Tnmoc.org, 2022, https://www.tnmoc.org/colossus#:~:text=Colossus%2C%20however%2C%20was%20the%20first,Manchester%20Small%20Scale%20Experimental%20Machine.

———. “Colossus Decrypts to be Revealed After 75 Years.” Tnmoc.org, 19 Feb. 2019, https://www.tnmoc.org/news-releases/2019/2/5/colossus-decrypts-to-be-revealed-after-75-years#:~:text=The%20full%20impact%20of%20Colossus,of%20such%20complexity%20using%20valves.

National Science Foundation. “A Brief History of NSF and the Internet.” NSF.gov, 13 Aug. 2003, https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=103050.

———. “The Internet—Nifty 50.” NSF.gov, 2000, https://www.nsf.gov/about/history/nifty50/theinternet.jsp#:~:text=Internet%20 expansion,expansion%20in%20that%20very%20month.

Nott, George. “Father of the Internet Vint Cerf: IPv4 Was Never Production Version.” Computerworld.com, 2 July 2018, https://www2.computerworld.com.au/article/643174/father-internet-vint-cerf-ipv4-never-production-version/.

Ormond, Cullen. “The Creation of the Printing Press.” UNG University Press, 18 July 2017, https://blog.ung.edu/press/the-creation-of-the-printing-press/.

O’Sullivan, Donie. “How the Cell Phones of Spring Breakers Who Flouted Coronavirus Warnings Were Tracked.” CNN Business, 4 Apr. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/04/tech/location-tracking-florida-coronavirus/index.html.

Our World In Data. “Daily Hours Spent with Digital Media.” Wikimedia Commons, 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daily_hours_spent_with_digital_media,_OWID.svg.

Petriglieri, Gianpiero, et al. “Thriving in the Gig Economy.” Harvard Business Review, Mar.-Apr. 2018, https://hbr.org/2018/03/thriving-in-the-gig-economy.

Pew Research Center. “Mobile Fact Sheet.” Pew Research, 7 Apr. 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

———. “News Consumption across Social Media in 2021.” Pew Research, 20 Sept. 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/09/20/news-consumption-across-social-media-in-2021/.

———. “Social Media Fact Sheet.” Pew Research, 8 Apr. 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

———. “The Rise in Apps Culture.” Pew Research, 14 Sept. 2010, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/09/14/the-rise-of-apps-culture/.

Saad, Lydia, and Ben Wigert. “Remote Work Persisting and Trending Permanent.” Gallup, 13 Oct. 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/355907/remote-work-persisting-trending-permanent.aspx.

Selber, Stuart. Multiliteracies for a Digital Age. Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Schiffrin, Anya. “Muckraking.” Oxford Bibliographies, 24 July 2018, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756841/obo-9780199756841-0211.xml.

Schuster, Jenna. “A Brief History of Internet Service Providers.” Internet Archive, 10 June 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20190428045452/https://www.exede.com/blog/brief-history-internet-service-providers/.

Shao, Grace. “Social Media Has Become a Battleground in Hong Kong’s Protests.” CNBC, 16 Aug. 2016, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/08/16/social-media-has-become-a-battleground-in-hong-kongs-protests.html.

Spotlite. “How Social Media Has Helped the Ukraine Humanitarian Crisis.” Spotlite, 2021, https://gospotlite.com/blog/social-media-helped-in-the-ukraine-humanitarian-crisis.

Star, Danny. “An Abbreviated History Of SEO and What It Tells Us about SEO’s Future Role.” Forbes, 28 Feb. 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/02/28/an-abbreviated-history-of-seo-and-what-it-tells-us-about-seos-future-role/?sh=40575c6d11ef.

Sundararajan, Arun. “The Gig Economy’ Is Coming. What Will It Mean for Work?” The Guardian, 26 July 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/26/will-we-get-by-gig-economy.

Team Recurrency. “The IoT Data Explosion: How Big is the IoT Data Market?” Priceonomics, 9 Jan. 2019, https://priceonomics.com/the-iot-data-explosion-how-big-is-the-iot-data/.

UNESCO. “Artificial Intelligence: Examples of Ethical Dilemmas.” UNESCO, 21 Apr. 2023, https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics/cases#:~:text=AI%20is%20not%20neutral%3A%20AI,Rights%20and%20other%20fundamental%20values.

U.S. Department of Commerce. “Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales: 1st Quarter 2022.” Census.gov, 19 May 2022, https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “SEC Charges Kim Kardashian for Unlawfully Touting Crypto Security.” Securities and Exchange Commission, 2022, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-183.

———. “Securities Act of 1933.” Securities and Exchange Commission, 24 Jan 2023, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-1884/pdf/COMPS-1884.pdf.

Visualwebz. “History of Google Analytics.” Medium, 1 Dec. 2021, https://seattlewebsitedesign.medium.com/history-of-google-analytics-fb7b23b6dee0.

Wharton Staff. “How Social Media is Shaping Political Campaigns.” Knowledge at Wharton, 17 Aug. 2020, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/podcast/knowledge-at-wharton-podcast/how-social-media-is-shaping-political-campaigns/.

Wong, Belle. “Top Social Media Statistics and Trends of 2023.” Forbes, 18 May 2023, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/social-media-statistics/.

World Wide Web Foundation. “History of the Web.” Web Foundation, https://webfoundation.org/about/vision/history-of-the-web/.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Profile Books, 2019.