History

4 The Protestant Reformation and Metrical Psalms

In this chapter you will

- explore the musical impact of the Protestant Reformation

- learn about the Bible and music in early colonial North America

- discover what meter is and how it allows the same words to be sung to different melodies

- create your own adaptation of a biblical text to a standard meter that can then be sung to a familiar tune

Do you know the first book printed in colonial North America? It was a collection of psalms known as the Bay Psalm Book. This tells us something about the centrality of the Psalms in the Protestant worship that these European colonists engaged in. The book was a collection of metrical psalms, meaning that the biblical psalms were translated not merely from the original Hebrew into English but into English verses that followed a regular meter. Meter in this context means a regular pattern of numbers of syllables and rhythms. Meter is not just a number of syllables; it also has to do with where the emphasis falls in words. That is why even though the tune “Yankee Doodle” has the same number of syllables in each line as the melody you know as “Amazing Grace,” you cannot sing the words of one of them to the other melody and have it sound right and natural. The melody traditionally used for “Amazing Grace” is in what is known as common meter, so called because it was and is so widely used. It consists of groups of four lines that alternate between eight and six syllables. You may see this abbreviated in metrical psalm collections as CM (for common meter) or 8.6.8.6, indicating the actual meter.

The slogan sola scriptura means “scripture alone.” This became a key slogan of the Protestant Reformation, emphasizing the Bible as ultimate (even if in practice never the only) authority.

The fact that the Bay Psalm Book was the first book to be printed in the American colonies tells us something. So too does the fact that a printing press was set up at such an early point. These facts together highlight some important things one can learn about the Protestant Reformation at the intersection of the Bible and music. You definitely will want to explore these things further if you are interested in this topic, and just as there are many copies of and exhibits about the Bay Psalm Book online, there are many introductions to the Protestant Reformation. In this context, we can sum up a few major points. One is an emphasis on individual Christians reading the Bible. English translations of the Bible are so numerous and widespread, and the act of reading it so common, that it can be hard to imagine a world without those things. The printing press was a major innovation around the time of the Protestant Reformation that made it possible and dovetailed into its emphases. Just as individual Christians should, according to Protestants, take responsibility for reading and interpreting the Bible, so too worship became more participatory, with all believers having the same access to God in prayer without a need for other human mediators and everyone joining together in song. Put these emphases together, and the composition of singable songs derived from Scripture is a natural direction to take things. In the seventeenth century, the English Puritan minister Thomas Ford called the singing of psalms a “Christian duty.”[1]

The Bay Psalm Book is in the public domain (not surprising given its age), and so it can be read online in a variety of places, including Google Books. You will undoubtedly find aspects of such an old book difficult to read, but at least take a peek inside.

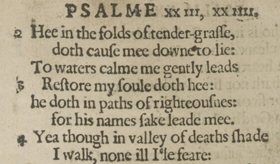

In order to adapt the psalms to a regular meter, it is inevitably necessary to paraphrase them at least somewhat. Some settings diverge more significantly from the source material than others. That’s the thing about translation and paraphrase: the one blurs into the other. No translation is without interpretation, and every genuine paraphrase remains connected to the meaning of the original. They represent a spectrum rather than two distinct and separate categories. Two settings by the famous hymnwriter Isaac Watts provide an example of how the same psalm might be rendered into metered English in two significantly different ways. Here are two renderings of Psalm 100, which he calls a “plain translation” and a “paraphrase,” respectively.

Two Renderings of Psalm 100 in Metrical Form by Isaac Watts

Psalm 100. A Plain Translation

Ye nations round the earth, rejoice

Before the Lord, your sovereign King;

Serve him with cheerful heart and voice,

With all your tongues his glory sing.The Lord is God; ’tis he alone

Doth life, and breath, and being give;

We are his work, and not our own,

The sheep that on his pastures live.Enter his gates with songs of joy,

With praises to his courts repair;

And make it your divine employ

To pay your thanks and honors there.The Lord is good, the Lord is kind,

Great is his grace, his mercy sure;

And the whole race of man shall find

His truth from age to age endure.

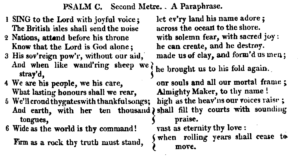

Psalm 100. A Paraphrase

Sing to the Lord with joyful voice,

Let every land his name adore;

The British isles shall send the noise

Across the ocean to the shore.Nations, attend before his throne

With solemn fear, with sacred joy;

Know that the Lord is God alone;

He can create and he destroy.His sovereign power, without our aid,

Made us of clay and formed us men;

And when, like wand’ring sheep, we strayed,

He brought us to his fold again.We are his people, we his care,

Our souls and all our mortal frame:

What lasting honors shall we rear,

Almighty Maker, to thy name?We’ll crowd thy gates with thankful songs,

High as the heav’ns our voices raise;

And earth with her ten thousand tongues

Shall fill thy courts with sounding praise.Wide as the world is thy command,

Vast as eternity thy love!

Firm as a rock thy truth must stand,

When rolling years shall cease to move.

Another famous setting of Psalm 100 has become known as “Old Hundredth” because it is one of the very early metrical settings of Psalm 100 (written by Louis Bourgeois in Geneva for use in Reformer John Calvin’s church), and its melody continues to be used to this day. There are many recordings of the psalm, including instrumental ones that you can sing along with. Here is a recording by the Harvard University Choir, conducted by Edward Elwyn.[2] The choir is accompanied by organ, which is how you will often hear it performed as well as sung in churches.

You will also find that some of these melodies have been arranged by famous composers (in this case, Ralph Vaughan Williams is an example) and that others may appear woven into other musical works. That’s not something we’ll explore here, but you may wish to if you haven’t had enough of this music or want to see how it has been influential beyond the boundaries of religious communities. In at least one famous instance, a melody originally composed for use with metrical psalms has become more closely associated with other words: many know the tune “Old Hundreth” as the music to which they sing words known as the “Doxology.”[3]

Some Reformed/Presbyterian churches practice exclusive psalmody, meaning they consider Psalms to be the only biblically authorized words for Christians to sing in worship.

Next you should try to participate in the singing and then the creation of metrical psalms yourself. Begin by singing along with some metrical psalms where the words and music are provided. Eventually, try adapting words from the Bible to a melody that you like, but start by finding a metrical psalm that already exists with words you like and then see if you can find a melody that suits it. Below I suggest some pairings of what may be familiar melodies with metrical psalms, but my musical tastes may not be yours, so look for ones that make sense for you. You can often find an instrumental karaoke track on YouTube to sing along with! Here are some suggestions:

Psalm 2 to the melody of “America the Beautiful”

Psalm 42 to the tune of the Gilligan’s Island theme

Psalm 113 to the melody of “House of the Rising Sun”

There are lots of different melodies that you already know that have a regular meter and thus to which it will be straightforward to sing any number of metrical psalms. There are free metrical psalm lyrics online, many being in the public domain, such as the Scottish Metrical Psalter of 1650. Metrical psalms also continue to be created, and there are recently published compilations that can be purchased. What happens when you sing an arrangement of a psalm to a tune you already know? What is the experience like? How does doing this influence your perception of the words and the music? Compare several different metrical arrangements of the same psalm. How do they convey the meaning of the original psalm in different ways? How much do they differ, and how much remains the same despite those differences?

For the record, the first printed book that we know for certain was published in the Americas was printed in Mexico. There is also very interesting early music from that era reflecting the Catholic tradition of the Spanish colonizers that draws on the Bible and more specifically the Psalms, with Hernando Franco’s “Circumdederunt Me” as one of the very first. Here is a performance by the Coro Melos Gloriae, conducted by Juan Manuel Lara Cárdena.[4]

For Further Reading

Anderson, Fred R. Singing God’s Psalms. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016.

Bertoglio, Chiara. Reforming Music: Music and the Religious Reformations of the Sixteenth Century. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017.

Duguid, Timothy. “Early Modern Scottish Metrical Psalmody: Origins and Practice.” Yale Journal of Music Religion 7, no. 1 (2021): 1–23.

Marín, Javier. “Hernando Franco’s Circumdederunt me: The First Piece for the Dead in Early Colonial America.” Sacred Music 135, no. 2 (2008): 58–64.

Stowe, David Ware. How Sweet the Sound: Music in the Spiritual Lives of Americans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Tierno, Alanna Ropchock. “The Lutheran Identity of Josquin’s Missa Pange Lingua: Renaissance of a Renaissance Mass.” Early Music History 36 (2017): 193–249.

- Thomas Ford, Singing of Psalmes the duty of Christians under the New Testament, or a vindication of that Gospel ordinance in V. sermons upon Ephesians 5. 19 (London: W. B., 1659). ↵

- The recording is shared by Memorial Church Harvard on their YouTube channel. ↵

- For those familiar with it or interested, the origins of the words for the Doxology can be traced to the hymnwriting career of Thomas Ken. ↵

- Shared by Enrique Guerrero on his Early Latin American Music YouTube channel. ↵