15 Writing a Preparation Outline

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Identify the benefits of outlining.

- Employ the principles of outlining to visualize arguments and clarify thinking.

- Construct a preparation outline.

In the previous three chapters, we discussed the importance of organizing your speech. We also named elements to include in your speech, such as an introduction, main points, and a conclusion. You may be wondering, “How will I know if I’ve included everything I need?” or “How can I see if my points make sense together?”

This chapter answers these questions by exploring the basics of outlining. An outline is a sketch or condensed version of your speech. We will focus on the preparation outline, which is the draft you write as you plan and organize your speech. It includes all your arguments, support, transitions, and citations. It helps you know if your points cohere together and if there are any gaps. Much of the hard but rewarding work of speech writing occurs while constructing and revising the preparation outline.

We begin by considering the importance of outlining for you and your audience. When we refer to the audience in this chapter, we mean your direct audience, who we described in chapter 10 as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech. Next we establish the principles to follow when crafting a Roman numeral outline. We conclude by explaining what to include in a preparation outline. For your reference, Appendix A and Appendix B offer full models of preparation speech outlines: one for an informative speech and one for a persuasive speech.

The Importance of Outlining

You may be tempted to avoid outlining and instead write your speech in free form or as an essay. We urge you to reconsider. Writing a well-crafted outline offers at least three benefits for speakers and audiences: It makes your speech more compelling, helps you identify and improve problems, and aids your memory of your speech.

You may be tempted to avoid outlining and instead write your speech in free form or as an essay. We urge you to reconsider. Writing a well-crafted outline offers at least three benefits for speakers and audiences: It makes your speech more compelling, helps you identify and improve problems, and aids your memory of your speech.

First, a preparation outline helps you arrange your ideas and supporting evidence in the most compelling manner. When you write a speech in free form, you can quickly lose your way and very quickly lose your audience too. Drafting your speech as an outline helps you focus on your thesis and visualize the linear or nonlinear arrangement you’ve chosen to support the thesis.

Second, the preparation outline helps you diagnose and address potential problem areas in your speech. The outline form allows you to locate points of repetition, gaps in reasoning, or extraneous information. You can more quickly determine if your main points are well balanced and if you have remembered to include an introduction and conclusion.

Finally, a preparation outline provides a visual representation of the speech, which helps you learn the speech. You can easily see your main points, so they become more memorable to you. You can also observe how transitions help you move from one point to another and how the introduction and conclusion open and close the speech.

Time spent constructing, arranging, and revising your speech outline now can reward you later, when audience members join your cause and have a clear sense of how to proceed. Outlining is the work you do to learn your speech, to know it well, and to communicate that deep knowledge to your audience. If you put the time in, it will show.

The presidential speechwriter Peggy Noonan said of speech preparation, “If you find yourself doing draft after draft, this is good. As you write and rewrite you are unconsciously absorbing, picking up your own rhythm and phrasing. This will show itself in a greater ease, a greater engagement when you stand up and give the speech. People will know that you know your text.”[1]

There are several specific guidelines that will help you write your preparation outline. Many instructors have strict requirements about how preparation outlines should look and what elements should be included, so be certain to check with your professor about their preferred format before you turn in your document. In the following section, we recommend general principles to follow when outlining.

The Principles of Outlining

The outlining system we present here is widely employed in public speaking courses, because it provides a visual representation of the structure of your speech. This visuality helps you see the relationship among your ideas, making the structure easier to develop and revise. Consequently, the principles are useful both for speeches that adopt a linear pattern of arrangement and for those that employ nonlinear patterns as discussed in chapter 13. Some instructors, however, may allow you to submit an outline that more visually matches a nonlinear pattern (i.e., appears as a star or as a spiral).

The outlining system we present here is widely employed in public speaking courses, because it provides a visual representation of the structure of your speech. This visuality helps you see the relationship among your ideas, making the structure easier to develop and revise. Consequently, the principles are useful both for speeches that adopt a linear pattern of arrangement and for those that employ nonlinear patterns as discussed in chapter 13. Some instructors, however, may allow you to submit an outline that more visually matches a nonlinear pattern (i.e., appears as a star or as a spiral).

Consistent Indentation and Symbolization

Make sure your outline is structured with a consistent pattern of symbols and indentations. Adopt a pattern of symbols that helps you visually differentiate main points from subpoints and quickly count the number of each. Avoid bullet points because they make these tasks much harder. Instead, main points should be identified by increasing Roman numerals, subpoints by sequential capital letters, and sub-subpoints by rising Arabic numerals. In addition, adopt a pattern of indentations to further distinguish types of points. Each Roman numeral should be flush left, each subpoint should be indented once, and sub-subpoints should be indented twice, as box 15.1 makes clear.

Box 15.1 Sample Indentation and Symbolization

Notice how each point uses sequential symbols (I, A, 1) and spacing (indentation or lack thereof).

I. First main point

A. First subpoint

B. Second subpoint

II. Second main point

A. First subpoint

1. First sub-subpoint

2. Second sub-subpoint

B. Second subpoint

III. Third main point and so on…

Indentation and symbolization help you see the flow of your speech and the relationship among your ideas. You can quickly observe, for instance, what your three main points are. You might discover an idea is not really a main point and functions better as additional support for a main point. This visual relationship among ideas is built on the principle of subordination.

Subordination

Subordination is the practice of making material that is less important, or primarily supportive, secondary to more central ideas and claims. Material in your outline should descend in order of importance. That is, supporting ideas or evidence should be listed under main points and indented.

Noting subordination is much different than writing an essay where subpoints are typically written with the claim they support as a single paragraph. Typically, paragraphs should be avoided when outlining. The subpoints instead should be visually subordinated.

Box 15.2 Sample Subordination

As Javon worked on his deliberation speech, he wanted to list the “benefits” and “drawbacks” of each potential solution or approach to the problem of concussions. These points he labeled “B” (benefits) and “C” (drawbacks). Underneath each of these points, and indented, he gave more detail about what the benefits and what the drawbacks were. This portion of his outline read as follows:

B. This approach foregrounds two benefits.

1. It tries to address the unhealthy aspects of hypermasculinity within football culture, like ignoring pain and ignoring the recovery protocols that may slow the chances of repeated concussion.

2. The education extends beyond players and coaches to include parents, fans, and community members who often perpetuate attitudes that celebrate players for sacrificing their bodies for the game.

C. But there are also drawbacks to this approach.

Here we see that points 1 and 2 are each listed under the claim “This approach foregrounds two benefits.” That’s because the individual examples of benefits (1 and 2) are subordinate to and support the claim that benefits exist (A). The drawbacks will similarly follow as points 1 and 2 under C.

Subordination is closely related to the next principle of outlining: coordination.

Coordination

Coordination is a visual representation of the proper relationship between ideas. It is related to subordination because it stresses that ideas of similar importance should be on the same level of the outline.

Box 15.3 Sample Coordination

Here is an example from Riley’s speech, discussing how members of the community can help spread awareness about animal abuse:

1. Use social media to broadcast pet news in our county.

a. Spread news about pet abuse and neglect to broaden awareness of this issue.

b. Spread news about current laws protecting animals.

c. Publicize agencies and phone numbers residents can call if they witness abuse or neglect.

d. Follow the Montgomery County Humane Society on Instagram and “like” them on Facebook.

Here we see coordination in that the four ways for community members to volunteer at the local animal shelter are listed on the same level of the outline: Each has a lowercase letter, each refers to subpoint 1, and each has identical indentation.

After you have sketched the subordination and coordination in your outline, you can turn to another important outlining principle: parallelism.

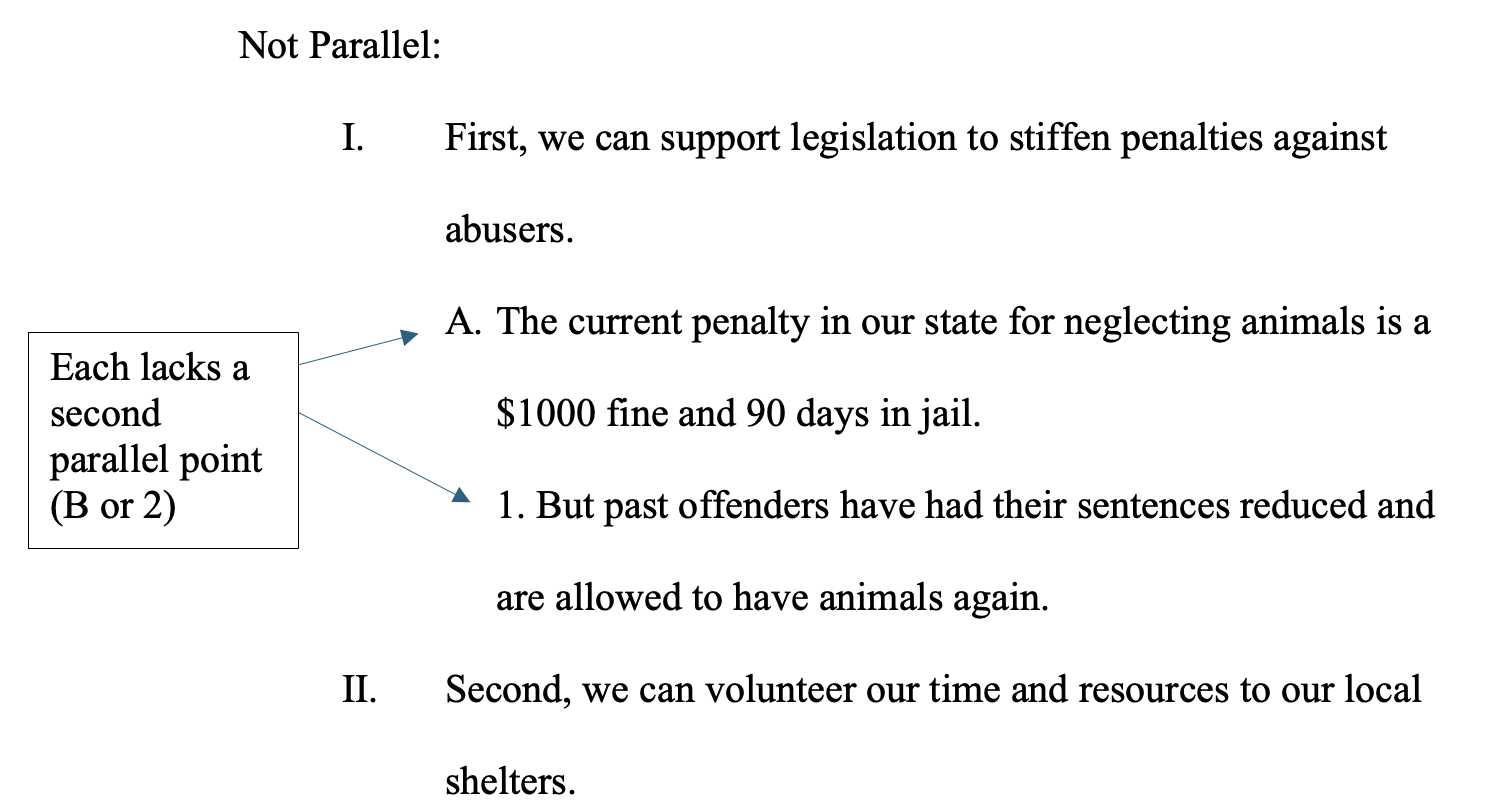

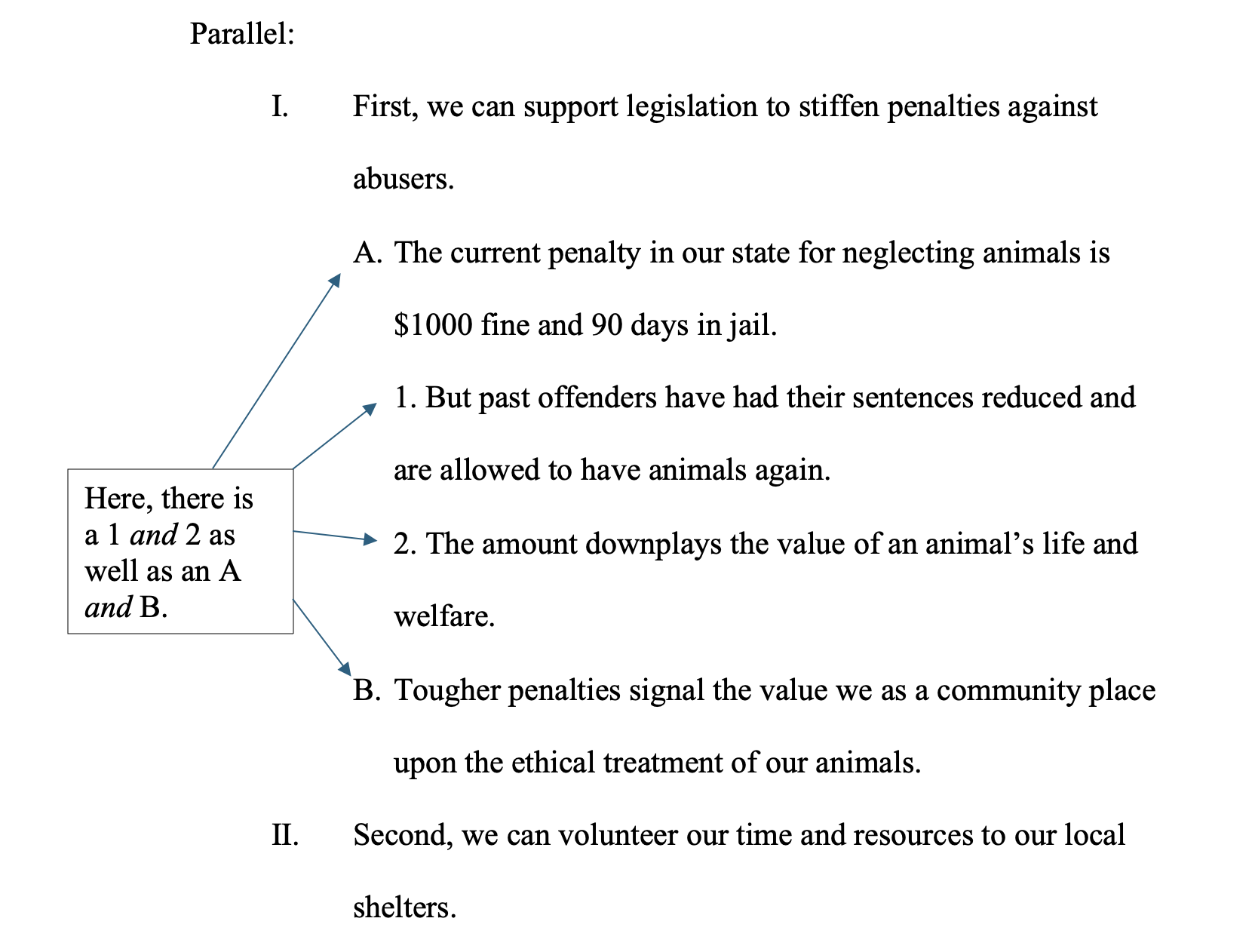

Parallelism

The parallelism principle dictates that you balance your points and subpoints as you divide them. Just as you cannot balance two ends of a scale with only one object, each level of your outline needs at least two points to be in balance or to justify the subdivision.

To explain this concept another way, we often say when it comes to outlining, “every little one has a little two.” In other words, there must be at least two relevant and worthy subordinate ideas to make the subdivision; otherwise, the division is not warranted.

Box 15.4 Sample Parallelism

Parallelism can best be illustrated through contrasting examples. Notice how the first example violates the principle of parallelism twice. Both subpoint A and sub-subpoint 1 lack a pair for balance. The second example provides such balance by adding subpoint B (to balance A) and sub-subpoint 2 (to balance 1).

Balance

The final principle of outlining is balance. Balance in speech outlining dictates each main idea receives roughly the same amount of time and attention in the speech. If the first main point of your speech lasts three minutes, the second main point lasts thirty-seven seconds, and the final main point is four minutes, then the audience suspects that your second “main” point really isn’t that important. An outline helps you visually detect such situations, because you can see how much or how little support you have included for each main point. If you find yourself with unbalanced points, consider adding or subtracting material to balance them.

Now that we have explained the guiding principles that will help you construct a coherent outline, we turn to the specific tasks of writing the preparation outline.

Constructing the Preparation Outline

As we said, the preparation outline is designed to help you think through and develop your speech. In a public speaking course, it is generally the version of a speech that you submit to your instructor, perhaps to receive feedback before you deliver the speech. Your preparation outline will be too detailed to serve as the notes you use to deliver your final speech, but writing a preparation outline is essential to the thinking and planning process. Unless your professor tells you otherwise, preparation outlines should include the following elements.

State Your Specific Purpose

The purpose statement is related to, but not the same as, your thesis statement. Another way to think of the purpose statement is as the overarching goal or objective for your speech. Since you are using this textbook, your purpose will likely be either informative or persuasive, so the verb you choose should reflect the goal (“explain” or “inform” versus “advocate” or “persuade”). Clearly label your purpose statement at the top of your outline. Here is Riley’s purpose statement.

Purpose statement: To urge audience members to become animal welfare educators in our county.

You will not state the purpose statement to your audience, but knowing and succinctly stating your purpose can help you write a good speech. If you do not know what you want your speech to accomplish, there is a good chance the rest of your speech will betray that lack of purpose.

Label Key Components of the Speech: Introduction, Conclusion, Thesis, Transitions

Visually highlight key components of the speech by labeling them in the outline. This helps you easily find them and better ensures they will fulfill their roles. The key components include the introduction and conclusion as well as the thesis and transitions.

First, clearly label the “Introduction” and “Conclusion” by writing those words with the Roman numeral assigned to each. Do not add any other information to the Roman numeral. Instead, the content of these points should appear below the Roman numeral and be indented to show subordination.

Second, label your “thesis” with that word whenever it appears in the outline. We discussed the characteristics of strong thesis statements at length in chapter 12. In your outline, labeling your thesis clearly will help you (and your professor) diagnose whether your central idea is well developed and is fully supported by the main points and subpoints.

The thesis’s location may depend on whether your speech is thesis driven or thesis seeking as we distinguished in chapter 14. If your speech is thesis driven, meaning the thesis “drives” or determines the route the speech will take, then the thesis will likely appear within both the introduction and conclusion (and should be labeled in each). If your speech is thesis seeking, meaning the introduction and main points build up to or “seek” a thesis, it is likely to appear only within the last main point and/or conclusion.

Box 15.5 Sample Labeling of the Introduction and Thesis in a Preparation Outline

Here is the introduction to Riley’s speech on animal welfare. Notice that only the label “Introduction” appears with Roman numeral I. The same would be true for the Conclusion, but with a different Roman numeral. Also notice that the thesis is noted as such, since it is a major speech component.

I. Introduction

A. In 2020, the Netflix documentary series Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness aired and became widely popular.

B. Many of you may have heard of or even watched Tiger King, or you may have laughed at parodies and memes of Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin. But how many of us focused on the animals who were treated cruelly?

C. Today I want to talk about this issue that is of great importance to me and I know to many of you as well. I’m an animal lover, and I became aware of pet abuse in our county through my volunteer work at the animal shelter. I was saddened by the Tiger King story and was motivated to do something locally.

D. (Thesis) There are several ways to support our local animal control agency’s power to remove and care for abused animals in Montgomery County, but the most important thing you can do is to increase awareness in our county so more people know what counts as abuse and how to report it.

E. In my speech, I will first establish the problem of animal neglect and cruelty in our county and state. Next, I will examine a frequently proposed solution and tell you why it will not make an immediate difference in the lives of our animal friends. Then I will advocate my preferred approach of educating the public about animal abuse, and I’ll tell you specific ways you can help spread the word.

Third, label each “transition” between main points by using that word. Transitions are crucial to how an audience makes sense of and follows your speech as you progress. Labeling your transitions in a preparation outline ensures that you include them and can find them easily. It also helps you evaluate the connections between main points and the flow of your reasoning.

Box 15.6 Sample Labeling of Transitions in a Preparation Outline

Within their speech, Riley included this transition to shift from the problem to an alternative solution:

* (Transition) Having addressed the problem of animal cruelty in our county and state, I will now turn to a potential solution to this problem.

Notice that “Transition” is explicitly labeled to draw attention to its presence and function.

Write Main Points, Subpoints, and Transitions in Complete Sentences

Except for the introduction and conclusion, which begin with only their labels, you should write every main point, subpoint, and transition as a full sentence. This is only true for the preparation outline because it helps you plan and organize your speech. Writing full sentences at this stage is a way to discipline yourself to complete your thought and fully prepare what you will say in your speech. Later, after you have developed your preparation outline and are ready to create speaking notes, you can remove full sentences and use keywords and phrases instead. We provide guidance on preparing speaking notes in chapter 19.

Include Spoken and Written Citations

As we explained in chapter 9, providing full citations for all your sources is a sign of ethical and responsible speech writing. That starts with the preparation outline. Include spoken citations—the source citations you plan to vocalize during the speech—in the outline itself. Add them wherever you plan to orally cite a source. Refer to chapter 9 for the specific information to cite each time.

As we explained in chapter 9, providing full citations for all your sources is a sign of ethical and responsible speech writing. That starts with the preparation outline. Include spoken citations—the source citations you plan to vocalize during the speech—in the outline itself. Add them wherever you plan to orally cite a source. Refer to chapter 9 for the specific information to cite each time.

In addition, include written citations within your preparation outline and at the end of this outline. Within the outline, add a written citation whenever you orally cite or draw information from a source. Each such written citation will likely appear similar to an in-text citation you might add to an essay. At the end of your preparation outline, on a separate last page, include a bibliography (or it might be called Works Cited

In addition, include written citations within your preparation outline and at the end of this outline. Within the outline, add a written citation whenever you orally cite or draw information from a source. Each such written citation will likely appear similar to an in-text citation you might add to an essay. At the end of your preparation outline, on a separate last page, include a bibliography (or it might be called Works Cited  or References). Be sure to check with your instructor about their preferred style guide (Modern Language Association, American Psychological Association, etc.).

or References). Be sure to check with your instructor about their preferred style guide (Modern Language Association, American Psychological Association, etc.).

Now that we have explained each element of the preparation outline, we encourage you to look at two full sample preparation outlines in Appendix A and Appendix B. One speech’s purpose is to inform an audience about the multiple approaches to a shared problem as they prepare to deliberate together. This type of speech is one you will learn more about in chapter 20. The other speech’s purpose is to persuasively advocate a particular solution to a problem (like you will learn more about in chapter 24).

Summary

This chapter stressed the importance of outlining and described general outlining principles that best produce a visual depiction of your organizational structure. It also explained the usefulness of a preparation outline and how best to construct one for your speech.

- Outlines have at least three benefits for you as the speaker: They help you arrange ideas in the best order for your purpose. They allow you to see where potential problems in evidence or logic emerge. They also help you learn the speech.

- Outlines should be written by following the principles of consistent symbolization and indentation, subordination, coordination, parallelism, and balance.

- Preparation outlines are full sketches of your speech, with ideas written in complete sentences to ensure complete thoughts. They label important elements such as the introduction and conclusion as well as the thesis and transitions. They follow outlining principles and include both spoken and written citations.

Key Terms

balance

coordination

outline

parallelism

preparation outline

purpose statement

subordination

Review Questions

- What are three reasons an outline is important for public speaking?

- Why is it useful to write the elements of your preparation outline in full sentences?

- How do the principles of consistent symbolization and indentation, coordination, subordination, parallelism, and balance help you develop a speech?

Discussion Questions

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of developing a speech by fully outlining it versus including large paragraphs?

- What parts of the outlining advice in the chapter seem the most daunting? The most useful? Explain your answers.

- Do you agree with the advice given in this chapter to avoid using bullet points in a speech outline? Why or why not?

- Peggy Noonan, Simply Speaking: How to Communicate Your Ideas with Style, Substance, and Clarity (New York: Regan Books, 1988), 24. ↵