16 Using Style to Harness the Power of Language

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Assess a speech’s style for how well it meets four core goals.

- Identify and distinguish common stylistic devices.

- Employ stylistic devices in a presentation.

If you live in the United States and speak English, do you use the word “pop,” “soda,” or “coke” to refer to a sweetened carbonated beverage? What kind of shoes do you wear: sneakers or tennis shoes? When you want to get others’ attention, do you say “you guys” or “y’all”?

These are just a few of the questions linguists Bert Vaux and Scott Golder asked Americans across the country in the early 2000s. Graphic artist Josh Katz updated and illustrated the responses with colorful maps for his 2016 book Speaking American. As you might expect, US residents differ considerably in their responses depending on where they live.[1] Your language probably reflects the words you heard where you grew up.

Of course, geographic region is just one of many factors that influence our word choice. Family upbringing, education, race, socioeconomic status, and age play roles too. Have you ever used popular slang terms with older adults, and they scratched their heads in confusion? If so, you know age contributes to language. What teenagers found “boss” in the 1960s, they called “rad” in the 1980s, “sweet” in the early 2000s, and “sigma” in the 2020s. That is, each generation develops its own style.

As defined in chapter 1, style is the language or expression we use—the words we choose. Style can significantly influence a message’s reception. To be an effective speaker, you must adopt a speaking style that suits your audience and purpose.

As defined in chapter 1, style is the language or expression we use—the words we choose. Style can significantly influence a message’s reception. To be an effective speaker, you must adopt a speaking style that suits your audience and purpose.

In what follows, we discuss four goals for style in public speaking. We then explore a few of the most helpful stylistic devices speakers can use to fulfill those goals.

The Goals of Style in Presentations

In everyday life, we often use style to mean how someone uniquely expresses themselves. Stylish people dress or walk in ways that exude sophistication, swag, or pizzazz. The same holds true for style in public speaking. A speaker who develops their personal speaking style is more likely to grab and hold their audience’s attention.

However, style can and should accomplish much more in public speaking. In this section, we discuss four desired outcomes of style: to create clarity, to maintain audience attention, to construct an appropriate mood or emotional state, and to generate a perspective on a topic for the audience. When we refer to the audience in this section, we are talking about your direct audience (unless we indicate otherwise). In chapter 10, we defined the direct audience as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech.

Clarity

Aristotle claimed that making ideas clear to the listener was the proper goal and result of all stylistic choices.[2] If a speech is composed primarily of technical terms, puzzling language, or unfamiliar words, audience members will not understand nor act upon the information presented. They will also not likely listen for very long.

Attention

Our language should capture and hold the attention of audience members. You have probably experienced boring or dry speakers. To be sure, this can be a product of delivery, but it is also an element of style. A speaker must create interesting, engaging images in our minds through words, such as by sharing vivid anecdotes, statistics, quotations, and rhetorical questions.

Emotion

Stylistic choices also help shape the emotional element of communication. Language can encourage listeners to overcome apathy by creating a feeling of intensity. Style also has the power to bring us together by emphasizing communal values and using inclusive words and phrases. Such feelings of unity can increase the persuasiveness of the message. Consequently, speakers must be ethical and reflective about the creation and use of such emotional bonds.

Perspective Creation

Finally, word selection has incredible power. Language shapes perspectives on the world—an idea we have alluded to in previous chapters.

Most of what we know we’ve learned through words rather than firsthand experience. For example, many people know a good bit about the country of China, including specific features of the topography such as the Yangtze River and the Great Wall, the population size, and its dramatic economic development over the last several decades. However, relatively few have traveled to China and seen any of this firsthand.

Words even influence how we perceive and react to things we do experience firsthand. For example, students sometimes describe their college education like a product they are purchasing from a business: “I need to get my money’s worth.” “The cost of time and money will pay off for me after graduation.” This metaphor turns students into customers and professors into service providers. Their relationship becomes purely transactional (an exchange of goods for payment) instead of potentially transformational to achieve a shared vision.

The words you choose to label or characterize your topic invite your audience to adopt a perspective on that issue. That means you must be especially thoughtful when talking about groups who are not part of your direct audience (and/or who will be impacted by your message). In chapter 10, we labeled these groups your implied and implicated audiences. The words you choose to describe them will shape your and your direct audience’s perspectives about them.

Style, then, is critical to forming your community’s attitudes, thinking, and even desire to act. Read box 16.1 for an example of how word choices shape your and your direct audience’s perspectives and actions.

Box 16.1 Word Choices Shape Perspectives and Actions

Imagine a drunk man sleeping in public.

- A court judge walks by, sees this publicly intoxicated man, and thinks, “Criminal.”

- A priest walks by, sees the same man, and thinks, “Sinner.”

- A medical doctor passes by next and thinks, “Sufferer.”

- A business owner walks by and thinks, “Loafer.”

Four different words are used to label the same person in the same situation, and each of these words is likely accompanied by a whole vocabulary. For example, along with “sinner,” the priest might use words like “repentance,” “forgiveness,” “God,” “weakness,” “spirit,” and “flesh.” The doctor, on the other hand, might adopt words like “blood alcohol level,” “addiction,” “healing,” “patient,” and “withdrawal.”

Each label—and the vocabularies that accompany them—evokes a different set of attitudes and likely encourages a different set of actions toward the man.

- The judge might fine or even incarcerate the man.

- The priest might attempt to bring the man to repentance to experience forgiveness and spiritual renewal.

- The doctor may medically examine him to help him physically recover.

- The business owner may simply walk past the man, determined to not hire him.

This example demonstrates the power of language to create each person’s perspective about, and (in)action toward, another person or group.

In sum, when chosen thoughtfully, your language choices should clarify your ideas, capture your audience’s attention, appeal to their emotions, and encourage them to adopt perspectives that facilitate community problem-solving. The next section examines specific devices you can use to help fulfill these goals.

Box 16.2 Tips for Meeting the Goals of Style

As you develop your speech, use this set of questions to reflect on and possibly revise your language choices. Doing so will help ensure your style fulfills the four core goals of style.

- Clarify the speaker’s ideas: Are all or most of the words you plan to say familiar to your audience? If not, will you supply clear definitions for words new to them? If you are using technical language, is it appropriate for your audience? If not, can you restate the ideas in more common language? How might you express your ideas in creative or imaginative ways that might better help the audience understand them?

- Maintain the audience’s attention: How well will your words themselves intrigue the audience? Can you communicate your ideas in interesting or engaging ways? How might language help the audience envision the problem or its solution?

- Evoke emotion: What words or phrases might help your audience feel strongly about the issue you will address? What forms of expression might move them to action? How might you adopt language to unify the audience in response?

- Create perspective: How might your labels and word choices shape the audience’s perceptions of the issue and the people affected? What vocabulary do you plan to employ, and what aspects of the issue does it highlight? Obscure? Which alternative labels and vocabularies could you use instead, and how might they shape the audience’s perceptions differently?

Stylistic Devices

Stylistic devices are language techniques and literary tools effective speakers use to present their ideas to their audience. These devices help fulfill the four goals previously covered by creating a sense of rhythm, providing visualization, enhancing argumentation, and developing a sense of community.

Rhythm

One effective function of stylistic language is to create a sense of rhythm in a speech. Rhythm helps maintain the audience’s attention because it creates a familiar and inviting pattern or cadence. Rhythmic language also heightens the audience’s emotions. There are several devices that develop rhythm, but here we briefly comment on four: parallelism, repetition, antithesis, and alliteration.

One effective function of stylistic language is to create a sense of rhythm in a speech. Rhythm helps maintain the audience’s attention because it creates a familiar and inviting pattern or cadence. Rhythmic language also heightens the audience’s emotions. There are several devices that develop rhythm, but here we briefly comment on four: parallelism, repetition, antithesis, and alliteration.

Parallelism

Parallelism is a series of ideas that is conveyed through language choices in a similar way. This can occur in a single sentence or across successive sentences. When he took the first steps on the moon, for example, astronaut Neil Armstrong famously said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” His repeated use of “one” followed by two words illustrated parallelism.

Box 16.3 Parallelism in Practice

An example of parallelism occurred in 2024 during a campaign speech by former South Carolina Governor and US Ambassador Nikki Haley when she ran for the Republican presidential nomination. About halfway through her speech, Haley shifted to the topic of national security: “Now let’s talk about national security. The world is on fire literally. You’ve got a war in Europe. You’ve got a war in the Middle East. You’ve got North Korea testing intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of hitting the US. You’ve got China on the march. But make no mistake, none of that would’ve happened had we not had that debacle in Afghanistan.”[3]

The four parallel phrases (each beginning with “you’ve got”) amplified anxiety about the country’s vulnerable and perilous state. They also invited listeners to join in the rhythm created, leading them to conclude that the country needs better leadership. Her final sentence bluntly ended the rhythm by blaming President Joe Biden for the calamities when she referenced his decision to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan in 2021.

Repetition

When using repetition, a speaker restates a word, sentence, idea, or theme. Repetition can emphasize a point and improve its retention. We often hear political leaders, for example, sprinkle a repeated phrase throughout their comments or even just within a sentence or paragraph.

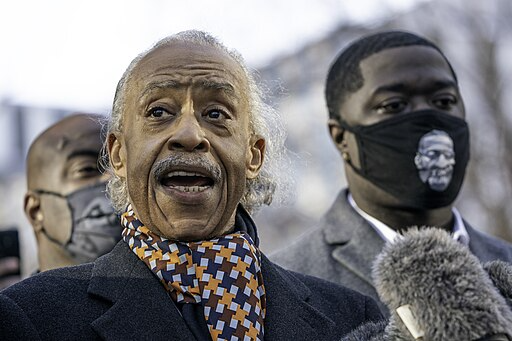

Box 16.4 Repetition in Practice

In August 2020, civil rights protesters organized a March on Washington in response to George Floyd and other Black Americans who died at the hands of police officers. During the event, Reverend Al Sharpton addressed the crowd from the same spot where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke in 1963 during the original March on Washington. At one point, Sharpton repeated a word to advocate for racial justice and police reform: “They keep telling me about how it’s a shame that Black parents have to have ‘the conversation’ with our children, how we have to explain if a cop stops you, don’t reach for the glove compartment, don’t talk back, the conversation. Well, we’ve had the conversation for decades. It’s time we have a conversation with America. We need to have a conversation about your racism, about your bigotry, about your hate, about how you would put your knee on our neck while we cry for our lives. We need a new conversation.”[4]

Sharpton’s repeated use of “conversation” cleverly shifted responsibility from Black parents to the broader country for keeping Black children safe during police interactions. It also created a sense of urgency for reform and built a connection with the audience through shared frustrations.

Antithesis

Antithesis is the juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, typically in the same sentence. For example, in his inaugural address, former President John F. Kennedy famously stated, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”[5] The contrasting commands (“Ask not” and “ask”) and the flipped positioning of words (“country” and “you”) are catchy to the ear and invite the audience to rethink a familiar idea.

Box 16.5 Antithesis in Practice

Civil rights activist and Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X delivered a famous speech, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” in 1964. He used a powerful antithesis wherein he contrasted a hopeful and patriotic sense of America (and identifying as American) with a cruel and exploitative characterization of the country: “No, I’m not an American. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. One of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but disguised hypocrisy. So, I’m not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver—no, not I. I’m speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.”[6]

The contrasting views of America climaxed in the last sentence with the direct antithesis between the dream and nightmare. The “American dream” was no doubt familiar to his audience, but the “American nightmare,” he argued, was his and other African Americans’ experience. His use of antithesis highlighted the difference between white and Black Americans’ lives, bringing sharp clarity and emotional intensity to the distinction.

Alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of a single consonant in a sentence or series of sentences. It’s prominent in tongue twisters such as “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” Alliteration is also frequently featured in songs and poetry because it can be melodic. In speeches, alliteration prompts us to repeat a phrase over in our minds.

Box 16.6 Alliteration in Practice

Beginning in the 1960s, Dolores Huerta helped farmworkers organize to advocate for better working conditions and payment. She cofounded the United Farmworker’s Association with Cesar Chavez in 1962 and helped organize several grape boycotts. In 1969, her proclamation of one such boycott included the following: “We did not choose the grape boycott, but we had chosen to leave our peonage, poverty and despair behind.…The boycott was the only way forward the growers left to us. We called upon our fellow men and were answered by consumers who said—as all men [sic] of conscience must—that they would no longer allow their tables to be subsidized by our sweat and our sorrow: They shunned the grapes, fruit of our affliction.”[7]

Her use of “peonage” and “poverty” as well as “subsidized by our sweat and sorrow” illustrates alliteration by the repeated use of the letters p and s. These repetitions helped make the statements melodic and memorable, thus augmenting their persuasiveness concerning the plight of farmworkers at the time.

Visualization

In addition to rhythm, stylistic language offers audiences visualization through vivid imagery. Such language heightens audience interest and helps an audience’s understanding and retention. Many stylistic devices can be used for visualization; here we highlight five: concrete language, visual imagery, simile, metaphor, and personification.

In addition to rhythm, stylistic language offers audiences visualization through vivid imagery. Such language heightens audience interest and helps an audience’s understanding and retention. Many stylistic devices can be used for visualization; here we highlight five: concrete language, visual imagery, simile, metaphor, and personification.

Concrete Language

Concrete language includes words that ground ideas in examples from the physical world. Good speakers move up and down the ladder of abstraction as they discuss their ideas. We can take the concept of transportation as an example. We can imagine a speaker discussing transportation and, as they do, also discussing automobiles, then American-made cars, and finally, Ralph’s beat-up 1975 metallic blue Ford Maverick. By moving “down” the ladder of abstraction, the speaker will make the concept of transportation concrete and easier for the audience to understand.

Box 16.7 Concrete Language in Practice

We find a gripping example of concrete language in President Ronald Reagan’s 1984 speech on the fortieth anniversary of the D-Day invasion of Normandy by American and Allied forces during World War II. He spoke at Pointe-du-Hoc, where American Rangers climbed the one-hundred-foot cliffs under heavy fire to take the strategic location during the invasion. Some of the surviving Army Rangers were seated before him as he spoke.

Reagan first described the events abstractly as when “the Allies stood and fought against tyranny” and the particular battle as when the Rangers “began to seize back the continent of Europe.” But then he turned to very concrete language to describe this battle:

We stand on a lonely, windswept point on the northern shore of France. The air is soft, but 40 years ago at this moment, the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was filled with the crack of rifle fire and the roar of cannon. At dawn, on the morning of the 6th of June, 1944, 225 Rangers jumped off the British landing craft and ran to the bottom of these cliffs. Their mission was one of the most difficult and daring of the invasion: to climb these sheer and desolate cliffs and take out the enemy guns. The Allies had been told that some of the mightiest of these guns were here and they would be trained on the beaches to stop the Allied advance.[8]

This powerful passage helps us appreciate how concrete language can clarify and drive home a much more abstract point.

Visual Imagery

Visual imagery is a way to describe ideas with word pictures so your audience can see in their mind’s eye a double-decker bus traveling through downtown London or a seagull flying in the sky above the beach in Santa Monica, California. The idea is to help your audience see, hear, and even smell and taste what you describe.

Box 16.8 Visual Imagery in Practice

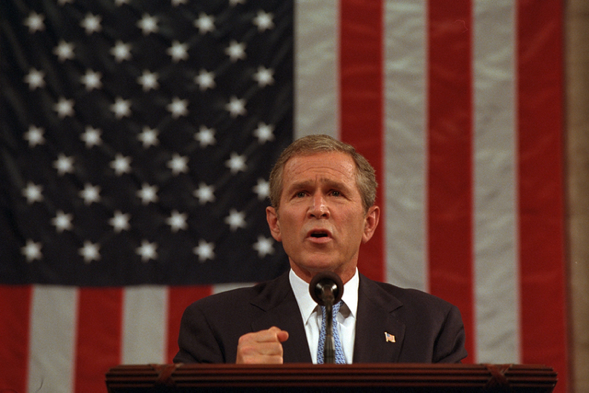

In his September 20, 2001, State of the Union address to Congress, President George W. Bush began with powerful visual imagery to help Americans see the country’s condition just nine days after the terrorist attacks of 9/11:

Mr. Speaker, Mr. President Pro Tempore, members of Congress, and fellow Americans, in the normal course of events, presidents come to this chamber to report on the state of the union. Tonight, no such report is needed; it has already been delivered by the American people.

We have seen it in the courage of passengers who rushed terrorists to save others on the ground. Passengers like an exceptional man named Todd Beamer. And would you please help me welcome his wife Lisa Beamer here tonight?

We have seen the state of our union in the endurance of rescuers working past exhaustion.

We’ve seen the unfurling of flags, the lighting of candles, the giving of blood, the saying of prayers in English, Hebrew, and Arabic.

We have seen the decency of a loving and giving people who have made the grief of strangers their own.

My fellow citizens, for the last nine days, the entire world has seen for itself the state of our union, and it is strong.[9]

Here President Bush used visual descriptions of actions his listeners could actually see in their minds to capture an abstract idea—that the state of the union of the United States was strong.

Simile and Metaphor

Metaphors and similes compare things that are essentially different. Similes make the comparisons explicit through keywords (e.g., “like” or “as”). For example, the great boxer Muhammad Ali described his boxing style in this way: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” Metaphors make comparisons implicitly. Box 16.9 provides examples of metaphors.

Box 16.9 Metaphor in Practice

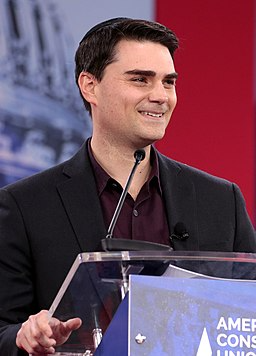

In 2024, conservative political commentator Ben Shapiro debated liberal political commentator Steven Bonnell, who goes by Destiny. While talking about the idea of free school meals to improve students’ education, Shapiro argued that improvements need to occur at a deeper level (such as increasing two-parent households). He explained, “It seems to me that one of the big flaws in the way that many people of the left approach government is, ‘What if we hit every gnat with a hammer?’ And my question is, what if the gnat isn’t even the problem? What if there is a much bigger substructure problem.…If you’re shifting deck chairs on the Titanic, sure, you can make the Titanic slightly more balanced because the deck chairs are slightly better oriented. But the real question is the water that’s gaping into the Titanic, right?”[10]

Here Shapiro compared student hunger to a gnat and free school meals to a hammer and then to Titanic’s deck chairs. In doing so, he helped listeners perceive meal programs as an excessively inefficient effort to target a minuscule contributor to poor student performance while ignoring the much bigger, more pressing cause.

Personification

Personification involves referring to an inanimate object or an abstract concept as if it were alive. Most often, personification works by giving human characteristics or abilities to something that is not human. For example, “Tradition richly rewards those who stick to the path she has set.” Here tradition is characterized as a person with the power to reward.

Box 16.10 Personification in Practice

In 2020, then–Senator Kamala Harris made history by being the first woman to be elected vice president of the United States. She was also the first Black person and Asian American to be vice president. In 2024, she became the first Black woman and Asian American to be a major party’s presidential candidate.

In her victory speech given on November 7, 2020, Harris celebrated becoming vice president and inspired children to recognize the US as a “country of possibilities.” She added, “And to the children of our country, regardless of your gender, our country has sent you a clear message: Dream with ambition, lead with conviction, and see yourself in a way that others might not see you, simply because they’ve never seen it before. And we will applaud you every step of the way.”[11]

In stating that the country had sent children a message, she personified the country to make the positive message for young people more vivid. She presented the whole country as speaking directly to young kids with dreams.

Box 16.11 Stylistic Devices

|

Rhythm |

Visualization |

Argumentation |

Community |

|

Parallelism |

Concrete language |

Irony |

Inclusive pronouns |

|

Repetition |

Visual imagery |

Satire |

Gender-neutral language |

|

Antithesis |

Simile and metaphor |

Reference to the unusual |

Maxim |

|

Alliteration |

Personification |

|

Ideograph |

Argumentation

A third function of stylistic language is to enhance argumentation. In other words, style choices themselves can help argue your case. Ideally, all stylistic language contributes to this end, but some devices do this particularly effectively. Metaphor is one device we have already discussed. Beyond metaphor, additional elements of style that directly advance argumentation include irony, satire, and reference to the unusual.

A third function of stylistic language is to enhance argumentation. In other words, style choices themselves can help argue your case. Ideally, all stylistic language contributes to this end, but some devices do this particularly effectively. Metaphor is one device we have already discussed. Beyond metaphor, additional elements of style that directly advance argumentation include irony, satire, and reference to the unusual.

Irony

Irony is the use of words in a way that is the opposite of their intended or normal use. For example, when someone says to you “nice shot” in a basketball game when the ball entirely misses the rim and backboard, they have employed irony. This technique functions as argument insofar as it offers an unexpected or surprising perspective on the underlying thought.

Box 16.12 Irony in Practice

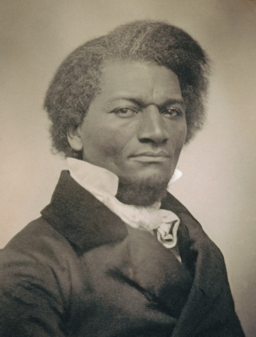

Frederick Douglass, an African American and former slave, was asked to speak in celebration of Independence Day in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852. His speech, “What to the Slave Is the 4th of July?” is recognized as one of the greatest speeches in American history.

Douglass answered the question in the speech’s title by noting that, ironically, it is a day that points out more than any other day of the year “the gross injustice and cruelty to which [the slave] is the constant victim.” He called out the disparity between his white audience members who enjoyed freedom and African American slaves who experienced oppression and brutalization: “The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me.” He continued: “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?”[12]

Douglass ended this passage with an ironic question. He was not actually asking his audience to answer, and he presumably knew they did not mean to mock him. By employing irony, Douglass highlighted ongoing injustice and shifted the audience’s emotions from celebrating America’s freedom from British rule to shamefully condemning the country for hypocritically maintaining slavery.

Satire

Satire is a particular form of ridicule that is typically used to attack people or ideas or to highlight human vices and failings. Rather than a specific speech element, satire often characterizes the entirety of a piece of discourse.

Box 16.13 Satire in Practice

Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby frequently employs satire in their performances. In a 2024 Netflix Special called Gender Agenda, Gatsby showcased several queer comedians but opened the show with their own spot.

During their comedic monologue, Gadsby referenced public debates about transgender athletes and, in particular, some male critics’ objections to trans female athletes participating in women’s sports: “I think it’s adorable how so many men are all of a sudden very concerned about women’s sport. That’s new. That’s real new. The idea that men are transitioning to become women so they can dominate women’s sports. Like, you know, pick up all those amazing perks you get in women’s sports!…Women get all the perks. They get kisses and everything.”[13]

Gadsby used satire to ridicule male critics’ concerns as disingenuous and wrongheaded. The satire prompted laughter at the critics, but it also held up for scrutiny a broader cultural devaluing of women’s sports. The comedian added irony to satire with the last sentence. It referenced the notorious kiss that former president of Spain’s soccer federation Luis Rubiales gave (without consent) to player Jenni Hermoso after her team won the Women’s World Cup in 2023.

Reference to the Unusual

In making use of a reference to the unusual, a speaker includes an unbelievable story or a startling statistic or fact to catch people’s attention and interest. The uniqueness and often surprising nature of such references encourage audience members to process and reflect on the reference.

Box 16.14 Reference to the Unusual in Practice

RuPaul Andres Charles (known simply as “RuPaul”) became nationally famous in the 1980s and 1990s as a drag queen who appeared in films and television shows and even recorded popular music. In 2009, he developed and starred in the competition television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, which has aired for many seasons.

In 2021, RuPaul hosted Saturday Night Live. During his opening monologue, RuPaul introduced himself: “My name is Ru which is short for RuPaul’s Drag Race. Now, for anyone who’s not familiar with my show, how dare you? And second of all, let me break it down for you in terms you can understand. So our girls gag us with their eleganza, death drop for the children, and slay the house down, boots. Make sense?”[14]

RuPaul’s description of the popular show used unusual language for anyone unfamiliar with it. The vocabulary—“eleganza,” “death drop,” “slay,” “boots,” and so on—likely piqued the curiosity and interest of novices as it demonstrated the drama and playfulness of drag. It simultaneously enabled devotees of the show to feel like true insiders of drag culture.

Community

Finally, speakers can utilize stylistic devices to create or reinforce the idea of community. Such devices are used to bring audiences together for a common cause or concern or to create separation between one audience (“us”) and an oppositional group (“them”). We might think about how speakers use stylistic devices to unite or differentiate their direct audience from their implied audience (referenced in the speech) and implicated audience (impacted by the message if it succeeds). Language tools that accomplish such ends include the use of inclusive pronouns, gender-neutral language, maxims, and ideographs.

Finally, speakers can utilize stylistic devices to create or reinforce the idea of community. Such devices are used to bring audiences together for a common cause or concern or to create separation between one audience (“us”) and an oppositional group (“them”). We might think about how speakers use stylistic devices to unite or differentiate their direct audience from their implied audience (referenced in the speech) and implicated audience (impacted by the message if it succeeds). Language tools that accomplish such ends include the use of inclusive pronouns, gender-neutral language, maxims, and ideographs.

Inclusive Pronouns

Inclusive pronouns are pronouns that create community and unity between the speaker and their direct audience and can be extended to include their implied and implicated audiences. Most prominently inclusive pronouns are the terms we, us, and our. The terms are used to create identity and put the speaker in league with their audiences, expressing shared purpose and concern, which can be particularly useful when a community experiences division.

Box 16.15 Inclusive Pronouns in Practice

In 2024, Steve Gleason won the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs. The former football player was diagnosed with ALS in 2011 and later formed Team Gleason to inspire other ALS sufferers to live meaningful lives. Gleason delivered his award acceptance speech from a wheelchair and through a speech-generating device.

He quickly pivoted, though, from talking about his own experience with ALS to “all of you who experience fear and suffering.” Referring to everyone in his direct, and possibly implied, audiences, he went on to say, “It’s clear to me that our ability to courageously share our vulnerabilities with each other is our greatest strength. By doing this, we’re able to understand the issue compassionately, collaborate with each other to solve problems and overcome fear.”[15]

In making use of the inclusive pronouns “our” and “we,” Gleason abolished divisions between people with ALS and people who have not developed ALS, and he bonded them together through shared experiences of fear. He used that bond to encourage his audience(s) to work together in more compassionate and collaborative ways in the future.

Gender-Neutral Language

Gender-neutral language refers to words that do not specify a particular gender. The meaning of gender-neutral language expanded during the twenty-first century.

Gender-neutral language refers to words that do not specify a particular gender. The meaning of gender-neutral language expanded during the twenty-first century.

Initially, it referred to language choices that do not explicitly or implicitly favor one gender over another. So, for example, instead of using terms like “policeman,” speakers should say “police officer” to avoid gendering the word as male. Speakers also should not make gender-biased assumptions, such as referring to nurses as female and to doctors as male.

Today, gender-neutral language also includes pronoun use. The Purdue Online Writing Lab, which many teachers and scholars turn to for guidance, explains:

He and she are not sufficient to describe the genders of all people, because not all people identify as either male or female. As such, the phrase “he or she” does not cover the full range of persons.

The alternative pronoun most commonly used is they, often referred to as singular they. Here’s an example:

Someone left his or her backpack behind. → Someone left their backpack behind.[16]

As part of adopting an effective and ethical speaking style, then, you should use a person’s preferred pronouns to refer to them—whether they are in your direct audience or part of your implied or implicated audiences. If their pronoun is unknown, then default to the neutral and singular “they.” Using singular “they” avoids the risk of misgendering someone and/or creating divisions rather than unity within a community.

Box 16.16 Using “They” as Singular

If it sounds oddly new or incorrect to use “they” for an individual, it’s not!

- The singular “they” first appeared in writing at least as far back as the fourteenth century.

- In 2019, Merriam-Webster added the singular “they” to the dictionary and made it the “word of the year.”

Maxim

A maxim is a statement of a general truth or rule of conduct believed by a culture, such as “the best defense is a good offense.” A maxim makes a main point accessible and memorable for the audience. However, don’t overuse this device or else your speech may seem trite or vacuous.

Box 16.17 Maxim in Practice

In her speech to the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Michelle Obama sought to respond positively to the negative political talk and growing polarization in the country.

Her efforts were noteworthy given her role as First Lady at the time and given the persistent and unfounded claims by critics that Barack Obama was not a United States citizen and therefore not eligible to hold the office of president.

Michelle Obama used a maxim to express what she believed is the most effective way to respond to untrue and hateful political claims: “When they go low, we go high.”[17]

This pithy phrase captured an honorable approach to politics in a polarized environment. Though it divided her direct audience (“we”) from an implied audience (“they”), it did so to encourage listeners to take the “high road” in politics and not return insult for insult. Listeners could extend her advice to interactions with such implicated audiences as their coworkers, friends, and family members.

Ideograph

An ideograph is a culturally specific term that has great emotive power because it represents a deeply held value or vice.[18] Core positive ideographs in American culture include “equality,” “freedom,” “liberty,” and “property.” Core negative ideographs include “terrorism,” “communism,” and “slavery.” Appeals to such values and vices generally need little elaboration and are accepted easily as rallying points for what is right or wrong even though their exact meaning is vague and unclear.

Box 16.18 Ideographs in Practice

During his 2024 acceptance speech as the Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump employed both positive and negative ideographs.

At one point he stated, “Today, our cities are flooded with illegal aliens. Americans are being squeezed out of the labor force and their jobs are taken. By the way, you know who’s taking the jobs, the jobs that are created? One hundred and seven percent of those jobs are taken by illegal aliens.”

The phrase “illegal aliens” functioned as an ideograph that likely triggered strongly negative and judgmental reactions about this implied and implicated audience. The label has become a kind of shorthand reference to people who are characterized as unwanted lawbreakers who don’t belong in the US. By fomenting fear and anger toward them, the ideograph helped Trump make a case for his needed return as president.

He later shifted to a positive ideograph when he proclaimed, “So tonight, whether you’ve supported me in the past or not, I hope you will support me in the future, because I will bring back the American dream. That’s what we’re going to do. You don’t even hear about the American dream anymore.”[19] The “American dream” represents a deeply, positively held vision and characterization of the country as a place of limitless possibilities. Trump’s use of the phrase helped associate his candidacy with this vision.

You can observe stylistic devices by examining the style of nearly any speech, from well-known presentations to everyday sermons and lectures. You may be surprised at the number and range of stylistic appeals in the discourse all around you.

Box 16.19 Using Stylistic Devices

- Incorporate stylistic devices that will appeal to your audience.

- Use stylistic devices in a manner that clarifies your points.

- Adopt stylistic devices to capture and maintain audience attention.

- Consider how stylistic devices can generate the best emotional tone for your speech.

- Reflect on how the devices you choose will shape the perspectives of your audience.

- Seek moderation in your use of stylistic devices.

Summary

In this chapter, we have addressed style, or the language or expression a speaker uses to communicate with an audience. Thoughtfully choosing words can help speakers engage their audience while clarifying the content, eliciting listeners’ emotions, and shaping their perspective. More specifically, this chapter has made the following clear:

- The stylistic use of language serves the important goals of creating clarity, maintaining audience interest, evoking emotion, and creating perspective.

- Stylistic devices are language techniques and literary tools that can be used to create a sense of rhythm (e.g., parallelism, repetition, antithesis, alliteration), enable visualization (e.g., concrete language, visual imagery, simile, metaphor, personification), enhance argumentation (e.g., irony, satire, reference to the unusual), and develop a sense of community (e.g., inclusive pronouns, gender-neutral language, maxims, ideographs).

Key Terms

alliteration

antithesis

concrete language

gender-neutral language

ideograph

inclusive pronouns

irony

maxim

metaphor

parallelism

personification

reference to the unusual

repetition

satire

simile

stylistic devices

visual imagery

Review Questions

- What goals should a speaker try to accomplish through their style?

- What are four devices to generate rhythm discussed in this chapter?

- What are five ways to foster visualization?

- What are the three devices mentioned to aid argumentation?

- What are four ways to build community through language choices?

Discussion Questions

- Think of a public presentation that had a particularly strong style. Which devices did the speaker use? What was their impact on the message and audience?

- What kind of style have you developed for presentations in the past? What kind of language did you use? How would you like to improve your style?

- How does—or should—style change based on the audience, setting, and occasion?

- Mark Abadi, “27 Fascinating Maps That Show How Americans Speak English Differently Across the US,” Business Insider, January 3, 2018, http://businessinsider.com/american-english-dialects-maps-2018-1. ↵

- Aristotle, On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse, trans. George A. Kennedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), sec. 1404b. ↵

- Nikki Haley, “Nikki Haley Speaks at South Carolina Campaign Rally” (transcript, Conway, SC, January 28, 2024), Rev, https://www.rev.com/transcripts/nikki-haley-speaks-at-south-carolina-campaign-rally-transcript, archived at https://perma.cc/H3VE-94N7. ↵

- Al Sharpton, “2020 March on Washington" (transcript, Washington, DC, August 28, 2020), Rev, https://www.rev.com/transcripts/al-sharpton-speech-transcript-2020-march-on-washington, archived at https://perma.cc/XC8A-J53F. ↵

- John F. Kennedy, “Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961,” in American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton, ed. Ted Widmer (New York: Library of America, 2006), 538. ↵

- Malcolm X, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” in American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton, ed. Ted Widmer (New York: Library of America, 2006), 576. ↵

- Delores Huerta, “Proclamation of the Delano Grape Workers for International Boycott Day,” Digital History, May 10, 1969, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=613, archived at https://perma.cc/6NYG-HPAB. ↵

- Ronald Reagan, “Remarks at a Ceremony Commemorating the 40th Anniversary of the Normandy Invasion, D-Day” (transcript, Normandy, France, June 6, 1984), Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum Archives, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/remarks-ceremony-commemorating-40th-anniversary-normandy-invasion-d-day, archived at https://perma.cc/7UG8-WQC7. ↵

- George W. Bush, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People” (transcript, Washington, DC, September 20, 2001), President George W. Bush White House Archives, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010920-8.html. ↵

- Lex Fridman, host, Lex Fridman Podcast, episode 410, "Ben Shapiro vs. Destiny Debate: Politics, Jan 6, Israel, Ukraine and Wokeism," January 23 2024, https://lexfridman.com/ben-shapiro-destiny-debate/. ↵

- Kamala Harris, “Speech after Historic Election Win” (transcript, Washington DC, November 7, 2020), ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/read-kamala-harris-full-speech-historic-election-win/story?id=74084644, archived at https://perma.cc/C9PN-TT7T. ↵

- Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave Is the 4th of July?" (transcript, Rochester, NY, July 5, 1852), EDSITEment: The Best of the Humanities on the Web, https://edsitement.neh.gov/student-activities/frederick-douglasss-what-slave-fourth-july, archived at https://perma.cc/MJE2-HBN6. ↵

- Hannah Gadsby, "Hannah Gadsby's Gender Agenda," Netflix stand-up special, 2024, https://www.netflix.com/watch/81607199?trackId=268410292&tctx=0%2C0%2C856d1017-c5d3-4bd6-add5-7bae4235b041-362449649%2C856d1017-c5d3-4bd6-add5-7bae4235b041-362449649%7C2%2Cunknown%2C%2C%2CtitlesResults%2C81607199%2CVideo%3A81607199%2CminiDpPlayButton, archived at https://perma.cc/C2NF-DFQH. ↵

- RuPaul, “Monologue” (transcript, New York, NY, February 21, 2020), SNL Transcripts Tonight, http://snltranscripts.jt.org/2020/rupaul-monologue.phtml, archived at https://perma.cc/GD85-A4WV. ↵

- Steve Gleason, “Acceptance Speech for the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs” (transcript, Hollywood, CA, July 11, 2024), Axios, https://www.axios.com/local/new-orleans/2024/07/12/steve-gleason-transcript-espys-acceptance-speech. ↵

- “Gendered Pronouns and the Singular ‘They,’” Purdue Online Writing Lab, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/grammar/pronouns/gendered_pronouns_and_singular_they.html#:~:text=When%20individuals%20whose%20gender%20is,range%20of%20people%20and%20identities. ↵

- Michelle Obama, “Remarks by the First Lady at the Democratic National Convention 2016” (transcript, Philadelphia, PA, July 25, 2016), President Barack Obama White House Archives, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/07/25/remarks-first-lady-democratic-national-convention, archived at https://perma.cc/4A6X-96MZ. ↵

- Michael Calvin McGee, “The ‘Ideograph’: A Link Between Rhetoric and Ideology,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 66 (1980): 1–16. ↵

- Donald Trump, "Convention Speech" (transcript, Milwaukee, WI, July 18 2024), New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/19/us/politics/trump-rnc-speech-transcript.html. ↵