2 Unproductive Public Discourse and the Politics of Polarization

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Describe the public sphere and the role of public discourse within that sphere.

- Analyze the qualities of unproductive discourse.

- Identify contemporary obstacles to productive communication.

Are you comfortable talking about controversial topics or politics, especially with people who disagree with you? Do you happily join in when someone mentions the current US president, abortion, or gun rights?

If you’re like most Americans, the answer is no. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, 61% of US adults—including both Democrats and Republicans—“say having political conversations with people they disagree with is generally ‘stressful and frustrating.’” Relatedly, that same survey found that 84% of adults say “political debate has become less respectful over the last several years,” and “78% say political debate has become less fact-based.”[1] Consequently, many of us avoid these conversations, sticking to safer topics like the weather or sports.

But even some previously “safe” forums and topics have become polarized and heated. Since the 2020 COVID-19 crisis, for example, many local school board meetings (that were “once orderly, even boring”) have erupted into angry exchanges over mask mandates, transgender students, and teaching about race.[2] In 2014, the most popular form of entertainment—video games—became particularly contentious. Using the social media hashtag “Gamergate,” “thousands of people in the games community began to systematically harass, heckle, threaten, and dox several outspoken feminist women in their midst.”[3] Even sports have prompted vehement disputes over players’ protests of police violence, over vaccination requirements, and over transgender athletes.

In this chapter, we diagnose the issues that plague public communication and consider how you can fix them. We begin by defining the public, public sphere, and public discourse. We then highlight problems with public communication, including the qualities of unproductive discourse. We end by identifying obstacles to more productive exchanges. Our goal is for you to reflect on how and why we, as democratic participants, so often publicly agree or disagree in ways that harm our relationships, public institutions, and democracy.

The Problems with Public Communication

Robust disagreement is necessary for a healthy democracy. Multiple, divergent perspectives and arguments allow for better discussions of public policy. Too often, however, our disagreements devolve into yelling matches and oppositional sides. To diagnose how and why, let’s begin by examining what type of speech counts as public discourse and what elements in that discourse are cause for concern.

The Public, the Public Sphere, and Public Discourse

For this textbook, a public refers to a collection of people who are joined together in a cause of common concern. Often a public works together to address an issue or question that affects their community. As a college student, you may consider the many publics of which you are likely a member: your residence hall or fraternity; your clubs, athletic teams, or student governance organizations; and even your major. Student athletes at your university, for example, may function as a public when they discuss, together, how they can travel to away games without missing too many classes.

In our definition, a public is distinctly different from a group of individuals. We might conceive of their differences in the following ways:

|

Individuals in a Group |

Members of the Public |

|

View themselves as separate entities or opposed sides |

Recognize their interdependency and common group identity |

|

Are driven by their own interests or needs |

Consider their own needs as well as those of fellow members, especially when needs conflict |

|

Usually believe their needs or concerns are in competition with other people’s needs and concerns |

Acknowledge the impacts of problems and attempted solutions beyond their own personal experiences and interests |

|

Think in terms of “me” versus “them” |

Think in terms of “us” |

|

Analogy: Competitors on a reality television show |

Analogy: Members of a sports team |

Our definition of a public draws heavily on the concept of the public sphere as articulated by the sociologist and philosopher Jürgen Habermas. For Habermas, the public sphere is the gathering of community members to discuss matters of common concern. The public talks, argues, and reasons together as equals, disregarding social and economic inequalities among participants, ideally arriving at a more fulsome understanding of the issues.[4]

When a public comes together to discuss matters of shared concern, they participate in public discourse. Public discourse refers to rhetoric that is publicly offered to address a significant community concern or issue. You likely hear public discourse on your campus about national politics, over local community projects, and regarding university student services ranging from dining options to financial aid. Several factors make a discourse public rather than private:

- the setting and participants (it is visible and accessible to anyone implicated by the decisions made there);

- the topics discussed (they impact a whole community); and ideally,

- the nature of the communication (it is concerned with the common good rather than the desires of a few individuals).

You can see, then, that “public,” the “public sphere,” and “public discourse” involve many members who may vary considerably from each other but who come together to discuss their shared concerns.

Growing Concerns About the State of Our Public Communication

When we look at the current state of our public discourse, we see we’ve developed bad habits. Scholars who have voiced concerns about our communication may help us understand what, precisely, is wrong with the way we talk to each other.

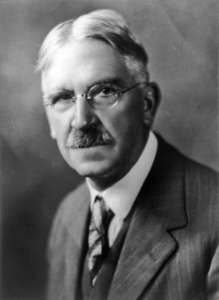

1927: The efforts to diagnose and correct our public discourse might be traced back to American philosopher and education advocate John Dewey and his book The Public and Its Problems. Dewey contended that more and better communication is necessary to improve the public and, hence, democracy.

“The essential need, in other words, is the improvement of methods of debate, discussion, and persuasion. That is the problem of the public.”[5]

1998: In the twentieth century, political theorist Benjamin Barber pointed to broadcast media as symbolic of more modern problems with public discourse in his book A Place for Us: How to Make Society Civil and Democracy Strong.

“Talk radio is loudly public without being in the least civil, though it is seductively entertaining. Unfortunately, its divisive rant is a perfect model of everything that civility is not: people talking without listening, confirming dogmas, not questioning them, convicting rather than convincing adversaries.”[6]

2021: A twenty-first-century characterization of the problems of public discourse was offered by political theorist Maxime Lepoutre in their book Democratic Speech in Divided Times.

“We find a public sphere saturated with emotional appeals, including intensely negative emotions such as rage and resentment. Instead of mutual respect, public speakers routinely use their airtime to ridicule, demean, or vilify others. And where sincerity should reign, campaigns of misinformation instead proliferate unimpeded.”[7]

How would you characterize US public discourse today? Would you agree that when you hear public figures talk about hot topics, you mostly hear ranting, emotional accusations, and ridicule? In this book, we label such talk “unproductive discourse.” We turn next to the central features of unproductive discourse that make it so problematic.

Qualities of Unproductive Discourse

Unproductive discourse is purposefully sensational public communication designed to promote division and to misrepresent the complexities of public issues. It features poor arguments that appeal to the least common denominator, name-calling that substitutes for nuanced analysis, and an emphasis on points of division rather than points of agreement. In fact, when we look across multiple examples, several such qualities repeatedly appear. These qualities include, but are not restricted to, the following: division, dichotomous thinking, combativeness, certainty, lack of listening, winning, distrust, hierarchical communication, dogmatism, and misinformation.[8] We consider each quality in box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Qualities of Unproductive Discourse

|

Division |

Highlights and accentuates differences among participants and their positions. |

“You aren’t from around here.” “They just weren’t raised like us.” |

|

Dichotomous thinking |

Features debate between two (and only two) diametrically opposed and extreme positions instead of exploring additional perspectives or middle ground. |

“Which side are you on?” “My idea will help women, and yours will hurt them.” |

|

Combativeness |

Utilizes aggressive behavior toward other participants and alternative perspectives, such as repeated interrupting, emotionally charged labels and terms, yelling, and personal attacks. Lacks empathy toward other participants and views dissenting opinions as the opposition to be defeated. |

“I can’t listen to your stupid ideas anymore.” “Why should we listen to a college dropout?” |

|

Certainty |

Exhibits sureness about a position without recognizing its weaknesses or drawbacks. Lacks self-reflexivity or room for doubt. |

“You’re wrong.” “My idea will benefit everyone.” |

|

Lack of listening |

Only listens to an alternative perspective to find weaknesses in it. Uses questions as veiled arguments or as attempts to humiliate other participants. Instead of truly considering the fellow participants, remarks seem directed at a third-party judge, moderator, or camera audience. |

“Isn’t it true that…?” “Can you even believe this guy?” |

|

Winning |

Fixates on getting one’s way, rather than learning or the common good, as the goal. At its worst, this form of communication uses any means necessary to win, such as providing false or misleading illusions, quoting statements out of context, and misstating or exaggerating the facts. Privileges emotion over logic and proof. |

“Your proposal will bankrupt every small family business.” “If you get your way, our country will be ruined.” |

|

Distrust |

Suspects other participants’ motives or goals. Presumes they have a hidden agenda and thus lacks faith in the honesty or authenticity of what they say. |

“Who are you really working for?” “Are you doing this for the spotlight?” |

|

Hierarchical communication |

Discourages communication among invested community members and instead encourages communication from the “top” decision-makers (officials, leaders, spokespersons, or experts) down, which subjugates everyday individuals’ preferences or insights. |

“Let’s listen to the mayor, who actually knows what she’s talking about.” “Are you just going from experience, or do you actually have a degree on this topic?” |

|

Dogmatism |

Features familiar and even predictable talking points as well as entrenched, predetermined positions. |

“Before I answer that, I’d like to make two points.” “As I’ve said before…” |

|

Misinformation |

Unintentionally propagates inaccurate or false claims that lack sufficient or valid evidence and/or identifiable and credible sources. |

“Everybody knows that…” “An insider told me…” |

Box 2.2 Unproductive Discourse in Practice

An example of problematic public dialogue was found in debates and legislation over drag shows. Although drag and drag performances have a long history, concerns over children’s exposure to them became prominently voiced in the US after 2017. A nonprofit organization called Drag Story Hour began organizing events where drag queens read books to children. While the goal was to promote literacy, inclusivity, and diversity, some people feared possible negative effects.

Instead of engaging in productive discussions about the reading hours, however, the disagreement escalated into unsubstantiated accusations and threats. Vocal opponents featured misinformation, distrust, combativeness, and certainty in their critiques.

- According to a Forbes article, conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, for instance, falsely accused drag queens of “having their way” with kids during story hours.

- Fox News personality Tucker Carlson told his audience that story hours are intended to “indoctrinate and sexualize children.”

- Baseless claims of drag queens “grooming” children spread on social media outlets like TikTok. Several states introduced, and some passed, legislation banning or criminalizing drag shows where children might be present, with some labeling the shows as “obscene” content.[9]

In response, drag queens and supporters utilized dichotomous thinking, division, misinformation, and combativeness in their self-defense.

- In late 2024, popular drag queen performer Jinx Monsoon, for example, stated that conservatives are “literally perpetuating lies.” She added, “Their whole agenda right now, it’s just all such blatant hypocrisy. Everything they accuse us of, there’s no data that supports it, and then they get caught doing the thing that they say queer people are doing.”

- In the same video, drag performer BenDeLaCreme argued, “Drag is not to be feared. Drag is about love, until you cross us. Then you better fear us, because we are strong. So back down or watch out, is how I feel about it.”[10]

- In March 2023, two drag supporters poked fun at conservative leaders through a comedic but combative Instagram account called “RuPublicans” that promoted misinformation by featuring AI-created images of GOP leaders in drag.[11]

- Defense of drag became more intimidating at a 2022 drag brunch in Texas, where supporters guarded the venue against protesters by dressing largely in black and holding AR–15 style weapons.[12]

Rather than productively discuss the potential benefits of, and concerns about, Drag Story Hour, several communicators used an array of unproductive discourse qualities. Consequently, they reduced the issue to two incompatible sides, depicted each other as opponents to be defeated, and provided little education about the issues of literacy, diversity, safety, and modeling.

Impacts of Unproductive Discourse

Unproductive discourse offers some benefits. It often captures our attention and entertains us. Catchy one-liners that require little knowledge can be exciting and fun to watch. Such rhetoric tends to evoke strong emotions from listeners, stirring people to care about issues they might otherwise ignore. It can also bring a sense of clarity to an issue by contrasting two sides.

However, the harmful outcomes produced by unproductive discourse overwhelm any advantages. Unproductive discourse typically lives up to its name in that it is, well, unproductive. It produces little new or reliable information, nor real understanding, as to why the participants or sides fundamentally disagree. Instead, it can miseducate us, since it overly simplifies complex issues and participants, overlooks additional perspectives, and spreads false information.

However, the harmful outcomes produced by unproductive discourse overwhelm any advantages. Unproductive discourse typically lives up to its name in that it is, well, unproductive. It produces little new or reliable information, nor real understanding, as to why the participants or sides fundamentally disagree. Instead, it can miseducate us, since it overly simplifies complex issues and participants, overlooks additional perspectives, and spreads false information.

Finally, unproductive discourse discourages us from becoming civically engaged because it emphasizes our divisions and turns us into spectators rather than participants. We are reduced to sitting on the sidelines and cheering or booing the participants. It’s not surprising that many of us opt out of the spectacle altogether, developing cynical attitudes about politics and civic affairs.

So what needs to change? The next section identifies recurrent obstacles to productive discourse that need to be addressed.

Obstacles to Productive Communication

There was never a golden era of respectful public discourse to which we hope to return. But there are at least five aspects of the situation today that exacerbate the problems: social media, the news media, the strategic use of incivility and disinformation, the marketing of ideas, and our own reluctant participation in democratic processes.

Social Media

Have you ever scrolled through social media and read a post that made you angry? Did you reach out to the person who posted it to thoughtfully discuss the topic? Or did you leave an angry comment or emoji, or even unfriend the person, and then move on to the next post? If you chose the latter, you’re not fully to blame.

Social media platforms encourage users to post things that will garner attention and emotional reactions. For public issues, that often means provocative or controversial claims that stir viewers’ emotions but rarely expand their understanding. Pair that posting incentive with communication restrictions (such as the number of characters allowed or typical post lengths), and you can see why social media are not designed to facilitate thoughtful discussions. Instead, they encourage, at worst, angry invective or, at best, an entertaining escape or mindless scrolling.

Artist and writer Jenny Odell claims, “The platforms that we use to communicate with each other do not encourage listening. Instead they reward shouting and oversimple reaction: of having a ‘take’ after having read a single headline.”[13]

Even people who refrain from making or commenting on posts are affected by the social media they consume. Algorithms that influence which posts we see tend to result in streams that largely reflect and reinforce our beliefs[14] and even steer us toward posts that feature anger and animosity.[15] Together, the types of posts we are exposed to and the content they highlight tend to sow oversimplification and emotional reactions and discourage curiosity, empathy, or listening.

News Media

Similar to social media, some news media frame, cover, and discuss issues in ways that emphasize conflict and talking points rather than depth and nuance. Cable news programs (e.g., FOX, CNN), in particular, frequently feature verbal fighting between people with differing views. Such news shows attract viewers, but they often make issues appear too immense or too unattractive for viewers to meaningfully engage.

News media shows on cable television tend to validate and valorize guests who stoke controversy and disagreement.

Incivility and Disinformation as Strategies

Two additional related, and more disheartening, obstacles are when public actors purposefully use ethically suspect tactics to impede meaningful discussions. One such tactic is what professor of public policy Susan Herbst calls “incivility as strategy.”[16] Most of us were probably taught growing up to avoid incivility, or offensive and rude behavior. Some public figures, however, purposefully choose incivility to gain attention and to silence detractors. Comments from radio and television personalities come to mind as a broad example, or attending a community forum and yelling to prevent a speaker from being heard.

The other tactic is the spread of disinformation. Misinformation is the unintentional spread of inaccurate or false claims that lack sufficient or valid evidence and/or identifiable and credible sources. It is listed as a quality of unproductive discourse because it hurts deliberation when speakers fail to double-check the validity of their information before passing it on. Even more harmful, however, is disinformation, which refers to the deliberate attempt to spread wrong information to mislead listeners. Like incivility, some public actors use disinformation strategically to attract support for their ideas or followers for their campaigns.

Box 2.3 Misinformation and Disinformation in COVID-19 Rhetoric

We can find examples of misinformation and disinformation in some of the public discourse around the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, President Donald Trump downplayed the virus’s threat and even promoted drinking disinfectant to combat it despite no supporting evidence. He and others in the White House also suggested, without evidence, that the virus was released by a lab in Wuhan, China.[17] In the summer of 2020, the US military capitalized on this false belief through a disinformation social media campaign that targeted the Philippines. To weaken China’s influence there, the military created false accounts that mimicked Filipinos and propagated lies about the virus and the vaccine under a slogan (in the language of Tagalog) that declared “China is the virus.”[18]

When politicians and powerful actors purposefully impede discussion and decision-making, we need different approaches to public discourse.

Marketing Ideas Rather Than Working Toward Compromise

The political arena has, in many ways, become more like corporate marketing, or the deliberate promoting and selling of products or services to consumers. Political strategists package politicians (especially candidates) and their ideas for an American consumer market. We watch thirty-second television commercials that advertise their family lives and values (with which almost no one disagrees), look at their official websites (which are nearly always clad in patriotic colors), and read memorable posts designed for social media. Civic engagement becomes reduced to simply choosing which candidate to “buy” with your vote—and later to choose which prepackaged policy to support. In the process, the public welfare becomes fragmented into demographic and interest groups, and individuals are reduced to passive consumers.

Reluctant Participation in Democratic Processes

Finally, we have ourselves to blame. How often do you research current issues? Contact your governmental representatives? Hold lively and respectful discussions with friends and family about controversial topics?

As members of a democracy, we too often do the following:

- Sit back and watch as decisions are made for us.

- Believe we are too busy to keep up with the issues or get involved.

- Defer to experts and authorities, wrongly assuming their powerful positions or knowledge will somehow enable them to promote the public welfare better than the public itself.

- Copy some of the more destructive discourse practices we see so frequently. We think that participating in a democracy means adopting a boorish persona and using the qualities of unproductive discourse.

Fortunately, there are ways to speak much more productively to bring about the change we wish to see in our institutions and communities. To improve our public discourse, many scholars and public thinkers have offered solutions to increase the quality of our public exchanges, and we outline these in the next chapter.

Summary

This chapter outlined the contemporary state of our public discourse. It explored the qualities of unproductive discourse, and it encouraged you to also think about a rhetoric’s broader impacts on the public sphere when evaluating communication. In this chapter, you learned the following:

- Public discourse today is largely problematic. It frequently features qualities we associate with unproductive discourse, partly due to the obstacles that prevent speakers from engaging in more productive forms of communication.

- Unproductive public discourse is characterized by the following features: division, dichotomous thinking, combativeness, certainty, lack of listening, winning, distrust, hierarchical communication, dogmatism, and misinformation.

- Obstacles to productive discourse abound. They include social media, the news media, the strategies of incivility and disinformation, the treatment of the political arena like a marketing campaign, and the inertia or disillusionment of many everyday people who choose not to become involved and change our public conversations.

Key Terms

certainty

combativeness

dichotomous thinking

disinformation

distrust

division

dogmatism

hierarchical communication

incivility

lack of listening

marketing

misinformation

public

public discourse

public sphere

unproductive discourse

winning

Review Questions

- What is the public sphere, and how is it related to public discourse?

- What are the qualities of unproductive discourse?

- What are some obstacles to productive discourse?

Discussion Questions

- Who are examples of public figures who practice unproductive discourse?

- Do you agree that in our contemporary culture we mostly hear and use unproductive discourse? Why do you think this is?

- Find an example of unproductive discourse. Which qualities do the participants exhibit? How so?

- Pew Research Center, “Americans’ Feelings About Politics, Polarization and the Tone of Political Discourse,” Americans’ Dismal Views of the Nation’s Politics, September 19, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/09/19/americans-feelings-about-politics-polarization-and-the-tone-of-political-discourse/, archived at https://perma.cc/ZBB2-M22D. ↵

- Stephen Groves, “Tears, Politics, and Money: School Boards Become Battle Zones,” Associated Press, July 10, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/health-education-coronavirus-pandemic-school-boards-e41350b7d9e3662d279c2dad287f7009. ↵

- Aja Romano, “What We Still Haven’t Learned from Gamergate,” Vox, January 7, 2021, https://www.vox.com/culture/2020/1/20/20808875/gamergate-lessons-cultural-impact-changes-harassment-laws, archived at https://perma.cc/4DJS-56WY. ↵

- Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996). ↵

- John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems (Project Gutenberg, 2023), 208, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/71000/71000-h/71000-h.htm. ↵

- Benjamin R. Barber, A Place for Us: How to Make Society Civil and Democracy Strong (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 115. ↵

- Maxime Lepoutre, Democratic Speech in Divided Times (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 2. ↵

- Conor Murray, “How Drag Queens Became a Right-Wing Target—from Alex Jones to Tucker Carlson—with These States Trying to Ban Story Hours and Shows,” Forbes, February 3, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/conormurray/2023/02/03/how-drag-queens-became-a-right-wing-target-from-alex-jones-to-tucker-carlsonwith-these-states-trying-to-ban-story-hours-and-shows/, archived at https://perma.cc/5AZL-HHC2?type=standard. ↵

- Ricky Cornish, host, Pride Today, “Jinx Monsoon & BenDeLaCreme Defend Drag Queens Against Republicans,” posted October 17, 2023, by Advocate Channel, YouTube, http://youtube.com/watch?v=TgcoBvbAidw. ↵

- Jay Valle, “Meet the ‘RuPublicans’: GOP Lawmakers Are Reimagined as AI-Generated Drag Queens,” NBC News, April 12, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-pop-culture/meet-rupublicans-gop-lawmakers-are-reimagined-ai-generated-drag-queens-rcna79136. ↵

- Gino Spocchia, “Conservatives Furious as Armed Men Turn Up to Protect Drag Performers at Texas Brunch Event,” Independent, August 30, 2024, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/dallas-drag-brunch-texas-protest-b2155624.html, archived at https://perma.cc/J3GN-JZPN. ↵

- We derived these qualities in part by considering the inverse or opposite of the qualities of “civil talk” proposed by Benjamin Barber in A Place for Us: How to Make Society Civil and Democracy Strong (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998). We return to Barber’s qualities of civil talk in the next chapter. ↵

- Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2019), 23. ↵

- Brendan Nyhan et al., “Like-Minded Sources on Facebook Are Prevalent but Not Polarizing,” Nature 620 (2023): 137–144, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06297-w. ↵

- Smitha Mill et al., “Engagement, User Satisfaction, and the Amplification of Divisive Content on Social Media,” arXiv, December 22, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.16941. ↵

- Susan Herbst, “Change Through Debate,” Inside HigherEd, October 4, 2009, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250829140151/https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/10/05/change-through-debate. ↵

- Benjamin Bell and Fergal Gallagher, “Who Is Spreading COVID-19 Misinformation and Why,” ABC News, May 26, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/US/spreading-covid-19-misinformation/story?id=70615995, archived at https://perma.cc/U2LT-AFQ5. ↵

- Chris Bing and Joel Schectman, “Pentagon Ran Secret Anti-Vax Campaign to Undermine China During Pandemic,” Reuters, June 14, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-covid-propaganda/. ↵