5 The Ethics of Public Speaking

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Explain the meaning of ethics and ethical codes.

- Complete the ethical responsibilities of preparing to speak in public.

- Practice the ethical communication behaviors expected of public discourse.

When preparing for a speaking occasion, you might be tempted to seek guidance and inspiration from past examples. Examining others’ speeches might uncover an ingenious theme, identify a clever reference, or clarify “what not to do.” Take a few notes from this speech, “copy and paste” a paragraph from another, venture into ChatGPT or Gemini to brainstorm topics and organize themes, and before you know it, you have a page or two of promising ideas. However, what is the difference between cultivating ideas based on other speeches and plagiarizing their content?

With so much information available at our fingertips, it is easy to commit an ethical misstep—whether due to being willfully deceptive, using unauthorized generative AI assistance, taking imprecise notes, and/or failing to attribute critical information. Such transgressions—and their consequences—explain why ethics is an important, and occasionally confusing, concern for public speaking.

We admit ethical questions are not always easy to answer. However, we also hold that there are recognized ethical practices that should govern our speaking and listening behaviors. In this chapter, we consider ethics in three dimensions: the relationship of ethics and rhetorical ethics, the ethics of speech preparation, and the ethics of speech performance.

Ethics and Rhetorical Ethics

Generally associated with the field of philosophy, ethics refers to a set of moral principles governing human conduct as it pertains to motives, ends, and the quality of one’s actions. The ethical quality of conduct is generally evaluated based on how it reflects what is deemed “good” or “bad,” or “right” or “wrong,” in a culture. We frequently use criteria such as honesty, morality, equality, and justice that are derived from culture, religion, upbringing, and community and institutional contexts to judge the ethics of a behavior.[1]

Ethical Codes

A more specific articulation of ethics is an ethical code, a set of rules or guidelines agreed to by a culture or group to regulate behavior. For instance, the American Medical Association (AMA) has a “Code of Medical Ethics” that is recognized as the “most comprehensive ethics guide for physicians.” With medical advances and changing legal guidance, the code is subject to reflection and debate. For instance, euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, abortion and some assisted reproductive technologies, and genetic testing and stem cell research present thorny dilemmas. However, the code provides physicians with principles to guide their professional conduct.[2]

College communities also typically have their own code of ethics, such as a university’s “rule of conduct” that governs student behavior and academic honesty. Common to such policies is a prohibition on cheating and plagiarism, including copying others’ work, wrongly taking credit for others’ words and ideas by failing to supply necessary attribution, and engaging in additional prohibited activities. You are probably familiar with the meaning of academic honesty at your institution—and if you are not, you should be. While such codes provide guidance to students, inevitably there are debates over their interpretation and enforcement. Perhaps you can point to important debates and discussions about your institution’s code of conduct or policies.

The Virginia Military Institute’s (VMI) honor system is one of the most historic ethical codes in higher education. At the heart of its system is the principle that cadets are “men and women of honor and integrity who can always be trusted” to follow their succinct code: “A Cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, nor tolerate those who do.”[3]

The difficulty in identifying a singular, universal ethical code is that individuals and communities have different worldviews, experiences, and values. Behavior that is accepted and expected in one community may be out of bounds in another. Actions we would dismiss as unethical in the abstract—lying, for instance—might be more complicated when put into specific contexts. The point is that ethical standards are community standards, and thus, we can expect disagreements about their meaning. However, that does not mean all actions are acceptable, only that ethical evaluations are based on many factors.

Rhetorical Ethics

While no single widely known code of rhetorical ethics exists on the level of the AMA’s “Code of Medical Ethics,” we can identify communication behaviors that are deemed acceptable and unacceptable. Rhetorical ethics, or the ethics of public speaking, refers to how we expect speakers and audience members to behave and interact as they communicate about matters of the public good. To that end, rhetoric scholar James Herrick identifies a set of ethical goods inherent across the history of rhetorical practice:

While no single widely known code of rhetorical ethics exists on the level of the AMA’s “Code of Medical Ethics,” we can identify communication behaviors that are deemed acceptable and unacceptable. Rhetorical ethics, or the ethics of public speaking, refers to how we expect speakers and audience members to behave and interact as they communicate about matters of the public good. To that end, rhetoric scholar James Herrick identifies a set of ethical goods inherent across the history of rhetorical practice:

(1) discovering truths and arguments relevant to decision-making on contingent issues,

(2) advocating, interpreting and propagating ideas before publics, and

(3) testing propositions in debate.[4]

When you, as a speaker, adhere to these practices, you enrich our public discourse. Moreover, you embody ethical rhetoric and reflect the qualities of productive discourse discussed in chapter 3.

We contend that rhetorical ethics involves the preparation of public speakers, the actions of speakers in presenting information, and as the next chapter explores, the listening behaviors of audiences.

The Ethics of Speech Preparation

Rhetorical ethics begins with the speech preparation process. This includes the commitment a speaker shows to an audience as well as the ethical choices made in the selection of information. While the next section on speech performance discusses the latter topic, here we consider speech preparation as an ethical demand.

Box 5.1 The Deceptively Hard Work of Speech Preparation

When done well, public speaking looks deceptively easy—it is “just talking,” after all. Few people fully appreciate how difficult it is to craft a successful presentation—the time it takes to develop the main idea, do the research, choose the language and tone, practice the delivery, and so forth. In fact, one might say we are trained to not notice these efforts.

Few football coaches give the sort of refined inspirational speech offered by Denzel Washington’s Coach Boone on the field of Gettysburg in Remember the Titans.

Few people can offer the type of on-the-spot—and spot-on—social commentary delivered by America Ferrera’s Gloria in Barbie as she recited the double bind of femininity and the crushing expectations of being a woman in contemporary society.[5]

When attending public lectures on your college campus, you probably have noticed that many speakers rely extensively on PowerPoint presentations or even use a full manuscript. You are justified in desiring more engagement from such speakers. But an expert’s reliance on their text reflects just how difficult public speaking can be, particularly when specific terminology is important. The point is that preparing a speech is hard work. America Ferrera and Denzel Washington are effective actors because they have honed their craft over many years.

Even nonactors like the late Steve Jobs, cofounder and chief executive officer of Apple, achieve speaking success, in part, due to their extensive preparation. Before his death, Jobs was a highly anticipated and captivating business speaker, and his “tech talks” were “must-see TV” for computer geeks and investors alike as he introduced new products and updates.

Watching Jobs, one might note his easy extemporaneous style, his eye contact, the engaging gestures, and the integration of his content with his visual aids. Although he tended to pace, it fit the persona he developed. In his appearances at the Macworld Expo, for example, Jobs appeared casual and relaxed, perhaps giving the impression that he had not prepared very much or was not trying very hard. On the contrary, this was part of the appearance Jobs worked diligently to cultivate. We are not suggesting that the accolades Jobs received as a speaker were unwarranted. Instead, they were achieved after a significant investment of time and effort.

Mike Evangelist, a former associate of Jobs at Apple, explained that Steve Jobs started preparing for his keynote addresses weeks in advance, not just developing his speech, but also reviewing all the products and technologies that might be relevant. Evangelist says that Jobs would go through multiple dress rehearsals that focused on every conceivable element with “no detail…overlooked.”[6]

What effective public speakers and performers have in common is that they take their development of public discourse—their speeches, their work—very seriously. They are responsible to their audience; they are ethical in their preparation.

The idea that speech preparation is not only important but also an ethical demand for speakers was well explained by Professor W. Norwood Brigance in a public speaking textbook chapter entitled “Four Fundamentals for Speakers.”[7] In his direct and challenging style, Brigance made clear how much work is required of public speakers: “Effective public speaking is a technique, as definitely as are the techniques of designing airplanes and removing appendixes, except that it is older and more complex than either.”[8] How can Brigance claim that public speaking is more complex than the precise calculations required to keep an aircraft in flight or the delicate movements necessary in surgery? His point is that there is not a single rote method for speechmaking, nor is there an equation available to guarantee success. With so many human factors and variables, public speaking requires constant revision and adaptation along with sustained attention to its preparation.

Box 5.2 Ethical Preparation

Elements of ethical preparation are addressed across this book, including instruction on research, reasoning, outlining, and delivery. Some of the more important practices that demonstrate ethical preparation for your public presentations include the following:

|

Advanced planning |

Begin working on your speech well in advance of its due date: at least one week, and longer for lengthier and more significant presentations. |

|

Information selection |

Research your ideas and select your supporting material carefully. |

|

Note-taking |

Take careful notes while researching in order to keep track of sources, catalog internet URLs, and properly attribute information. |

| Revision and refinement |

Engage in revision and refine your ideas as you develop the presentation. |

|

Practice |

Practice your presentation multiple times before giving it to a public audience. |

| Responsibility and respectfulness |

Make your message meaningful to your audience out of respect for their time. |

Another Brigance maxim to which we subscribe is his belief that a speaker “must earn the right to give every speech.”[9] While many people “like to talk” or “like to debate,” they overlook the responsibility that comes with the opportunity. When you are given a chance to speak, it comes with a corresponding ethical responsibility to take the occasion seriously and to come prepared with something meaningful to share. See box 5.2 for advice on practices important to ethical speech preparation.

The Ethics of Speech Performance

Every so often, we learn that a high-profile speaker unethically took another person’s ideas. Perhaps you know of such an example. But why does it matter if the speaker did not invent their speech? Does it really change how an audience should understand and respond to the rhetoric? Yes, it very well might. In this section we examine the ethics of public influence and five ethical practices important to public communication.

The Ethics of Public Influence

Perhaps the central reason rhetorical ethics is important is that audiences make decisions based on the public discourse they hear. We form judgments based on listening to commencement speakers, reading a trusted information source on the internet, and even when making travel decisions after seeing a forecast from the local meteorologist.  In each case, rhetors communicate information the public uses in decision-making: How can I best contribute to society? Which candidate should I vote for? What can I do about environmental problems in my community? Is it safe to travel today? Public rhetoric—your rhetoric—has consequences for which you are responsible, and thus you have an ethical duty to your audience.

In each case, rhetors communicate information the public uses in decision-making: How can I best contribute to society? Which candidate should I vote for? What can I do about environmental problems in my community? Is it safe to travel today? Public rhetoric—your rhetoric—has consequences for which you are responsible, and thus you have an ethical duty to your audience.

Your rhetoric has consequences: Audiences make decisions based on what you say to them!

Box 5.3 Fact-Checking a President

Because the public makes choices based on the rhetoric of elected officials, some news outlets increasingly “fact-check” their public statements. In likely the most visible stance on the topic, starting in 2016, The New York Times began pointing out what it felt were misleading statements by Donald Trump rather than just reporting what he said.

- This started by taking a stand against then-candidate Trump’s “Birther Lie” concerning the birthplace of Barack Obama.

- It continued by chronicling “Trump’s Lies” after his first year in office during his first term as president.

- The newspaper proceeded by recording how his public statements between the 2020 presidential election and the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot contained “persistent repetition of lies.”

- The paper later identified Trump’s “frequently false” statements during a June 2024 presidential debate as a candidate for a second term as president.

- It persisted by documenting his “‘Machinery’ of Misinformation” during Trump’s second term.

It is easy to question the stance of The New York Times as the product of the “liberal media,” but its approach is notable in repeatedly calling out a president for the accuracy of his statements. It does so because public discourse influences the decisions that the public and voters make.[10]

National Communication Association (NCA), the largest organization of communication scholars and practitioners in the United States, has a Credo for Ethical Communication that provides a useful perspective on responsible communication behaviors. In part, the credo holds:

Questions of right and wrong arise whenever people communicate. Ethical communication is fundamental to responsible thinking, decision-making, and relationship building, and community development within, and across, contexts, cultures, channels, and media. Moreover, ethical communication enhances human worth, human life, and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others. We believe that unethical communication threatens the quality of all communication and consequently the well-being of individuals and the society in which we live.[11]

The NCA Credo goes on to list principles at the core of ethical communication, including

- advocating “truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication”;

- condemning “communication that degrades individuals and humanity through distortion, intimidation, coercion, and violence, and through the expression of intolerance and hatred”; and

- accepting “responsibility for the short- and long-term consequences for our own communication” while expecting “the same of others.”

You should quickly recognize that qualities consistent with the NCA Credo have been promoted in the opening chapters of this book—and appear central to The New York Times’s criticism of Donald Trump’s rhetoric (in box 5.3). Similarly, if you review the explanations of productive discourse from earlier chapters, you will see a close connection between its practices and the NCA’s expectations for ethical communication.

Box 5.4 Artificial Intelligence and Ethics

Advanced artificial intelligence, more commonly known as generative AI, is rapidly reshaping the world in significant ways, including how content is produced. A quickly expanding and ever-changing array of generative AI chatbots and AI assistants are available, including ChatGPT, Claude, Google Bard, Bing Chat, and Gemini.

Increasingly, members of the workforce need to understand how to use generative AI, and colleges need to teach their students about effective, ethical use. The extent to which generative AI acts as a supplement, as opposed to a replacement, for independent work is an important part of the conversation. We advocate measured, thoughtful use of generative AI in ways that improve and refine the speechmaking process rather than substitute for it, maintaining an emphasis on the importance of independent learning of the fundamentals of speechmaking. Here are some considerations to make before you use generative AI as well as how to use it:

Ethically Using Generative AI

- Examine any policies your school has on the use of AI in academic work.

- Discuss any potential use of AI with your instructor in advance of utilizing it.

- Follow any policies or parameters for AI use set out by your instructor: What your instructor says determines the contextual, ethical use of AI for your work on that speech and in that class.

- Track and cite your AI use to keep it transparent, including search inputs supplied to the AI. Chapter 9 provides specific instructions on how to cite your use of AI.

- Verify any information you locate using AI rather than simply relying on what the AI generates.

Using Generative AI as a Feedback Tool

- Use AI to brainstorm leading arguments and counterarguments on your topic.

- Use AI to identify policy options and solutions.

- Use AI to identify the strengths and weaknesses of your outline so you can improve it.

- Use AI to polish your writing and make writing suggestions.

- Use AI to prepare for questions the audience might ask about your speech.

Limiting Your Reliance on Generative AI

- Don’t rely on AI to locate and cite sources. Some generative AI make up sources, including citations that seem plausible but are not factually accurate. Chapter 9 also discusses this tendency.

- Don’t rely on generative AI to provide accurate information. AI is limited based on the resources available to it.

- Don’t rely on AI to generate complex and engaging prose.

The quality of AI-generated content is quickly improving with each iteration of AI chatbots, but limitations to source material and writing quality remain. Such issues have occasionally emerged in controversial and problematic ways, including in the creation of legal briefs that have relied on faulty information. There are also important questions related to bias in the language and stereotypes used by some AI, the material generated by AI, and efforts to detect it. These concerns range from the limitations of facial recognition, to generation of imagery, to faulty accusations of AI use that have been levied, particularly against nonnative English writers and speakers.[12]

Ethos and Five Ethical Practices of Public Communication

When engaging in public speaking, there are five ethical practices that deserve additional attention: plagiarism, ethical research, sound reasoning, respectful language, and taking responsibility for consequences. In each case, a violation results in a loss of ethos. Aristotle identified ethos as one of three modes of proof used for invention. Ethos refers to the state of one’s public character or persona—what we commonly call credibility. In the context of public speaking, ethos involves an audience’s perceptions of a speaker’s trustworthiness, competence, goodwill, and dynamism.[13]

As listeners, we assess a speaker’s credibility to help determine how much merit to place on their message:

- Does the speaker seem honest and of high integrity (trustworthiness)?

- Do they—by reputation, expertise, or performance—demonstrate themselves as capable (competence)?

- Do they appear to care about the audience’s welfare (goodwill)?

- Is their performance engaging (dynamism)?

All these components have ethical implications, although, understandably, it is the expectation of trustworthiness that is most often invoked in ethical evaluations.

Box 5.5 Five Ethical Practices of Public Communication

|

Ethical practice |

Meaning |

How to avoid ethical violations |

|

Avoid plagiarism |

Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of another’s words or ideas as one’s own. |

Do not submit another’s work as your own or use the ideas of others without acknowledgment. |

|

Conduct ethical research |

Ethical research involves proper practices for locating, using, evaluating, and citing research and sources. |

Cite your sources; do not overstate or manipulate evidence; do not fabricate evidence; do not suppress counterarguments. |

|

Practice ethical and sound reasoning |

Ethical and sound reasoning requires making reasonable claims supported by quality evidence. |

Do not base arguments on assertion or overly rely on pathos and fear appeals. |

|

Use language ethically |

Ethical language recognizes the value and humanity of others by using accurate language and recognizing one’s identity. |

Do not use rude, vulgar, sexist, heterosexist, or racist language that demeans others, dismisses their identity, and lessens their human value. |

|

Be responsible for the consequences of your rhetoric |

The speaker who is responsible for the consequences of their rhetoric recognizes and accepts that their communication influences the decision-making of others. |

Do not ignore the implications of your persuasion or evade responsibility for the actions and policies you advocate. |

Avoid Plagiarism

The most commonly recognized ethical responsibility of a speaker is to refrain from plagiarism. Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of another’s words and ideas as one’s own. As a college student, you should understand the importance of original work that is free of plagiarism. You should also understand the need to uphold academic honesty, which avoids all forms of cheating. Original, ethical work is expected from you because it is fundamental to learning, and it is a core component of honesty.

The most commonly recognized ethical responsibility of a speaker is to refrain from plagiarism. Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of another’s words and ideas as one’s own. As a college student, you should understand the importance of original work that is free of plagiarism. You should also understand the need to uphold academic honesty, which avoids all forms of cheating. Original, ethical work is expected from you because it is fundamental to learning, and it is a core component of honesty.

In a public speaking class, it constitutes plagiarism if you submit as your own a speech, outline, or paper prepared by someone else. Plagiarism also includes using language and ideas developed by another source without appropriate citation. Submission of such work is dishonest and thwarts the educational process. Even if you develop delivery skills through the performance of someone else’s work, you cannot learn the speechmaking process, which ranges from topic selection, to thesis development, to research, to argumentation.

Generative AI raises new and complex questions surrounding original work. You should discuss any use of AI for speechmaking with your instructor in advance and acknowledge any use of AI within your work. See box 5.4 for further considerations on the ethical use of AI as part of the speechmaking process.

Plagiarism is a concern not only in the classroom but also in society. Several public figures, from politicians to academics, have been accused of plagiarism. These instances (considered in box 5.6) underscore the need to carefully document sources and to not use others’ work as your own. Failing to do so can have devastating consequences and creates the need for public explanations and apologies.

Box 5.6 Case Studies: Plagiarism in Society

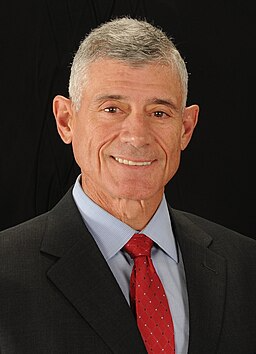

In May 2021, University of South Carolina president Robert Caslen resigned after acknowledging that aspects of his commencement speech plagiarized a 2014 commencement address given at the University of Texas by retired Navy Admiral William McRaven, who was tasked with leading the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. In an acknowledgment that parallels the scenario that opens this chapter, Caslen wrote, “I was searching for words about resilience in adversity and when they were transcribed into the speech, I failed to ensure its attribution. I take full responsibility for this oversight.”[14]

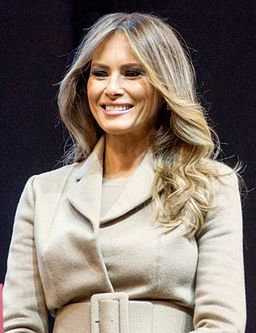

Another high-profile incident involved the 2016 Republican National Convention speech given by Melania Trump. The initially well-received speech, which in part discussed Ms. Trump’s upbringing in Slovenia, contained several passages and themes that echoed Michelle Obama’s address at the 2008 Democratic National Convention. In the tumult that followed, a Trump Organization staff writer took public responsibility for the error of “inadvertently” leaving “portions of the Obama speech in the final draft.”[15]

These examples demonstrate the importance of taking care during the research process to prevent plagiarism and the consequences of such acts.

Conduct Ethical Research

As the examples from Robert Caslen and Melania Trump in box 5.6 illustrate, plagiarism also reflects failings of ethical research and, most specifically, proper practices for using supporting materials. These ideas are addressed with additional depth in our discussions of research (chapters 8 and 9) and reasoning (chapters 26 and 27). Here we are interested in how source use involves important ethical considerations. So while ethical research implicates issues of plagiarism—for instance, not citing sources or giving the impression that the ideas or words of others are your own—it also extends to the larger realm of academic dishonesty based on how research is gathered and credited.

Speakers commonly face the issue of how to give proper credit to sources. In written work there is the expectation that we use formal modes of documentation ranging from in-text acknowledgment of a source, to endnotes, to bibliographies. Since an oral presentation is a different format, there is sometimes confusion over how to approach such issues. However, the basic expectation is that materials that merit citation in written form also merit citation in an oral form. Chapter 9 specifically addresses how to orally cite research and more thoroughly addresses its importance.

Keep in mind that all sources should appear in a bibliography submitted with any outline you prepare, and you should be able to supply source information to audience members on request. Ultimately, a good rule of thumb is when you are uncertain if material needs to be cited, err on the side of inclusion and provide a verbal acknowledgment.

Beyond citation there are three additional ethical issues related to the use of sources:

- Do not overstate or manipulate evidence. Representing evidence accurately rather than manipulating it to fit your desired conclusion is necessary to establish public or audience trust. Remember that the information you convey can influence decision-making.

- Do not fabricate evidence. Even if you are confident that the evidence exists, do not take a shortcut by inventing what you think you know. Instead, locate credible evidence for the idea and cite it. If you cannot locate the evidence, then the legitimacy of your assumed conclusion is also in doubt.

- Do not suppress counterarguments and opposing evidence. Instead, acknowledge them. This is important because it allows a community to thoroughly consider policy options, particularly since some in your audience are likely aware of such evidence. It is through addressing counterevidence that you can supply important analysis and refutation that can ultimately strengthen your case. Chapter 25 provides guidance for how to acknowledge and refute counterarguments when developing a persuasive speech.

Practice Ethical and Sound Reasoning

A third ethical responsibility for speech performance is that we make reasonable claims supported by evidence. We must not rely merely on assertion, a claim that lacks an evidentiary basis and is offered without reason, support, or data.

Relatedly, we must balance appeals to pathos, more commonly called emotional appeals, with the use of reason. Pathos refers to the psychological state of the audience and rests upon a speaker’s effective, ethical appeals to the audience’s emotions and motivations. Like ethos, pathos is part of the rhetorical canon of invention identified in chapter 1.

Relatedly, we must balance appeals to pathos, more commonly called emotional appeals, with the use of reason. Pathos refers to the psychological state of the audience and rests upon a speaker’s effective, ethical appeals to the audience’s emotions and motivations. Like ethos, pathos is part of the rhetorical canon of invention identified in chapter 1.

However, relying exclusively on pathos in ways that deter critical thinking is unethical. For instance, it is unethical to ignore the facts of a situation in favor of preying on an audience’s fears. Overly relying on fear tends to discourage thoughtful, reasoned analysis. Chapter 33 offers an analysis of a speech that engaged in this practice.

Use Language Ethically

Fourth, as a speaker it is your responsibility to respect your audience by using ethical language. Words are crucial to our understanding of the world and help construct identities. Through our words we can bring a community together to pursue improvements or divide it and hinder such progress. Think about competing ways to discuss substance addiction, transgender persons, or national identity and ethnicity. Our language can be constructive and inclusive in advancing dialogue, or it can severely undermine it.

Therefore, it is important to avoid rude, vulgar, sexist, heterosexist, and racist language as we treat audience members humanely. Sexist, heterosexist, and racist language excludes audience members and denies their value as fellow community members by perpetuating negative perceptions. The labels, metaphors, and euphemisms used to characterize groups of people make it easier to dismiss them and sometimes to even forget their humanity. Similarly, inaccurate naming or pronoun use dehumanizes those included in the discussion and/or those being talked about.

Certainly, we might use unethical language unintentionally, but to do so willfully—for instance, by intentionally ignoring an individual’s pronouns—is to deny and damage identity, reinforce stereotypes, and purposefully disrespect the people involved. The ethical speaker thinks about the context within which they are communicating, attempts to avoid charged or hateful language, and discusses people and objects in appropriate and accurate terms.

Be Responsible for the Consequences of Your Rhetoric

Finally, the ethical speaker considers and accepts the consequences of their rhetoric. Remember, people base decisions on what you say. Therefore, you must consider the consequences of your message for them.

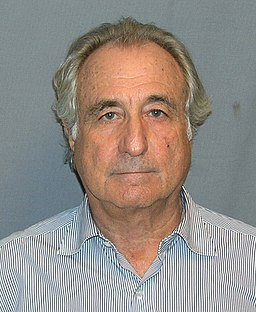

Box 5.7 Case Study: Irresponsibility for Consequential Rhetoric

A spectacular example of an “investment advisor” who acted fraudulently is Bernie Madoff. Thousands of investors lost billions of dollars when they gave Madoff control of their assets. While they assumed the monies were being invested, Madoff was actually keeping many of the assets. There were devastating consequences for investors, with many losing a good portion or all of their life savings. In a similar fashion, in 2024 Samuel Bankman-Fried was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison after he was found to have defrauded investors and lenders to his cryptocurrency exchange corporation FTX of nearly $3 billion and been untruthful about how their funds were used.[16]

A public speaker may not cost an audience member their retirement nest egg, but the point is the same: There are consequences to what you say, and you must consider those consequences in forming your message. Just as we expect that investment advisors have training and act ethically in their dealings, we expect public speakers who advocate actions and policies to behave similarly.

There are, no doubt, other ways a speaker can fail to satisfy their ethical obligations, but we have offered five ideas at the core of ethical speaking behavior. Use these principles as a checklist to review your speech preparation prior to delivering a presentation to ensure you are practicing ethical communication.

Summary

This chapter explored the importance of rhetorical ethics in maintaining the reputation of rhetorical practice and making public deliberation possible. Public speaking ethics includes the ethics of speech preparation and the ethics of speech performance. Specifically, in this chapter we observed the following:

- Ethics and ethical codes are used to evaluate our behaviors.

- Rhetorical ethics provides guidelines for the practice of public communication.

- A casual attitude about ethics has profound implications of a personal and public nature. Ethical faults lead to negative personal evaluations and a loss of ethos, thereby damaging one’s personal and professional opportunities.

- There are significant public implications to unethical behavior, including poisoning public discussion, making reasoned decision-making more difficult, and leading publics toward unwarranted conclusions.

- Sound rhetorical ethics begins with the speech preparation process as we earn the right to address audiences by being prepared, well informed, and practiced.

- Ethical speaking behavior also means being mindful of our conduct as a speaker and, in particular, avoiding plagiarism, practicing ethical research, bringing forward reasonable claims that are supported by evidence, treating audiences with respect, and taking responsibility for the consequences of our rhetoric.

Key Terms

assertion

community standards

ethical code

ethical language

ethical research

ethics

ethos

pathos

plagiarism

rhetorical ethics

Review Questions

- What is meant by ethics? Rhetorical ethics?

- What is ethical speech preparation?

- What is meant by the ethics of public influence?

- What are five ethical practices of public speaking?

Discussion Questions

- What is your school’s code of conduct? What is your school’s plagiarism or academic honesty policy? How is your work in public speaking related to that code and policy?

- What are the most important things you can do to be an ethical speaker?

- How common is unethical communication? Where is it most prominent or frequent? Why?

- Richard Johannesen, “Ethics,” in The Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition, ed. Theresa Enos (New York: Garland, 1996), 235. ↵

- “Code of Medical Ethics,” American Medical Association, https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/, archived February 23, 2025, at https://perma.cc/LR3S-K5CT. ↵

- “Honor System,” Virginia Military Institute, https://www.vmi.edu/cadet-life/cadet-leadership-and-development/honor-system/, archived February 23, 2025, at https://perma.cc/YQX8-4XM5. ↵

- James A. Herrick, “Rhetoric, Ethics, and Virtue,” Communication Studies 43 (1992): 139, 144-45, https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979209368367. ↵

- HBO Max, “America Ferrera's Iconic Barbie Speech,” posted December 22, 2023, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBqlDWHkdHk. ↵

- Mike Evangelist, “Behind the Magic Curtain,” The Guardian, January 5, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2006/jan/05/newmedia.media1. ↵

- William Norwood Brigance, Speech: Its Techniques and Disciplines in a Free Society (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1952), 16–24. ↵

- Brigance, Speech, 16. ↵

- Brigance, Speech, 23. ↵

- Michael Barbaro, “Donald Trump Clung to ‘Birther’ Lie for Years, and Still Isn’t Apologetic,” New York Times, September 16, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/17/us/politics/donald-trump-obama-birther.html; Callum Borchers, “Why The New York Times Decided It Is Now Okay to Call Donald Trump a Liar,” Washington Post, September 22, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/09/22/why-the-new-york-times-decided-it-is-now-okay-to-call-donald-trump-a-liar/; David Leonhardt and Stuart A. Thompson, “Trump’s Lies,” New York Times, December 14, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/23/opinion/trumps-lies.html; Larry Buchanan et al., “Lie After Lie: Listen to How Trump Built His Alternate Reality,” New York Times, February 9, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/09/us/trump-voter-fraud-election.html; Michael Gold, “Trump’s Debate Performance: Relentless Attacks and Falsehoods,” New York Times, June 28, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/27/us/politics/trump-debate-performance-falsehoods.html; Steven Lee Meyers and Stuart A. Thompson, “In His Second Term, Trump Fuels a ‘Machinery’ of Misinformation,” New York Times, March 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/24/business/trump-misinformation-false-claims.html. ↵

- “Credo for Ethical Communication,” National Communication Association, 1999, revised 2024, https://www.natcom.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Credo-for-Ethical-Communication-Revised-Clean-2024.pdf. ↵

- Pranshu Verma, “Michael Cohen Used Fake Cases Created by AI in Bid to End His Probation,” Washington Post, December 29, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/12/29/michael-cohen-ai-google-bard-fake-citations; Benjamin Weiser and Jonah E. Bromwich, “Michael Cohen Used Artificial Intelligence in Feeding Lawyer Bogus Cases,” New York Times, December 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/29/nyregion/michael-cohen-ai-fake-cases.html; Lyle Moran, “Lawyer Cites Fake Cases Generated by ChatGPT in Legal Brief,” Legal Dive, May 30, 2023, https://www.legaldive.com/news/chatgpt-fake-legal-cases-generative-ai-hallucinations/651557/; Aniya Greene-Santos, “Does AI Have a Bias Problem?,” NEA Today, February 22, 2024, https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/does-ai-have-bias-problem, archived at https://perma.cc/C8FL-64FN. ↵

- Richard D. Rieke, Malcolm O. Sillars, and Tarla Rai Peterson, Argumentation and Critical Decision Making, 7th ed. (New York: Pearson, 2009), 155. ↵

- Travis Caldwell and Amanda Jackson, “A University President Resigned After a Recent Plagiarized Speech. It’s Not the First Commencement Address Lifted,” CNN, May 14, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/14/us/plagiarism-commencement-speech-south-carolina/index.html; Becky Sullivan, “University of South Carolina President Resigns After Plagiarizing Part of Speech,” NPR, May 13, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/05/13/996523535/university-of-south-carolina-president-resigns-after-plagiarizing-commencement-s, archived at https://perma.cc/C2GX-DHWW. ↵

- Jason Horowitz, “Behind Melania Trump’s Cribbed Lines, an Ex-Ballerina Who Loved Writing,” New York Times, July 20, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/21/us/politics/melania-trump-speech-meredith-mciver.html; Brett Neely, “Trump Speechwriter Accepts Responsibility for Using Michelle Obama’s Words,” NPR, July 20, 2016, https://www.npr.org/2016/07/20/486758596/trump-speechwriter-accepts-responsibility-for-using-michelle-obamas-words; Maggie Haberman and Michael Barbaro, “How Melania Trump’s Speech Veered Off Course and Caused an Uproar,” New York Times, July 19, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/20/us/politics/melania-trump-convention-speech.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=b-lede-package-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news. ↵

- Office of Public Affairs, “Samuel Bankman-Fried Sentenced to 25 Years for His Orchestration of Multiple Fraudulent Schemes,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 28, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/samuel-bankman-fried-sentenced-25-years-his-orchestration-multiple-fraudulent-schemes; Rob Wile, “Sam Bankman-Fried Sentenced to 25 Years in Prison for Orchestrating FTX Fraud,” NBC News, March 28, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/sam-bankman-fried-sentenced-25-years-prison-orchestrating-ftx-fraud-rcna145286. ↵