7 Standpoint Theory and Ethical Rhetoric

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Use standpoint theory to describe the impact of social identities on knowledge.

- Explain the mythical norm.

- Appraise how standpoint theory influences ethical speech preparation, speech performance, and listening.

The previous two chapters explored how choices concerning your speech preparation, speech performance, and listening can help you practice ethical communication. This chapter introduces standpoint theory to further enrich that understanding.

We will first explain standpoint theory and the related concept of positionality. We will then turn to the ideas of intersectionality and the mythical norm. We will end the chapter by using these theories and concepts to reflect again on the ethics of public speaking.

Standpoint Theory

Standpoint theory emerged from feminist philosophy in the 1970s and 1980s to help explain how we gain knowledge and form perspectives.[1] The theory suggests that our standpoint—which is produced by our social identities—influences our knowledge of the world. As philosophy scholar Briana Toole explains, “Knowledge is sensitive to features like your race, your sex, your gender, your sexual orientation, your class, your religious affiliation, and so on.”[2] Our social identities impact how we are perceived and interact with the world. In other words, our social identities play a role in how we are treated, what we are (or are not) encouraged or expected to do, where we can (or cannot) easily go, and where and when we are invited to speak. Those experiences influence what we know.

Standpoint theory emerged from feminist philosophy in the 1970s and 1980s to help explain how we gain knowledge and form perspectives.[1] The theory suggests that our standpoint—which is produced by our social identities—influences our knowledge of the world. As philosophy scholar Briana Toole explains, “Knowledge is sensitive to features like your race, your sex, your gender, your sexual orientation, your class, your religious affiliation, and so on.”[2] Our social identities impact how we are perceived and interact with the world. In other words, our social identities play a role in how we are treated, what we are (or are not) encouraged or expected to do, where we can (or cannot) easily go, and where and when we are invited to speak. Those experiences influence what we know.

For instance, a dark-skinned American Sikh man wearing a turban is more likely in the United States to be treated with suspicion (or even hate) and mistaken as Muslim than, say, an American white man wearing a baseball cap.[3] Consequently, the Sikh man likely knows more about racism, islamophobia, and microaggressions in the United States than the white man, who is less likely to experience them.

For instance, a dark-skinned American Sikh man wearing a turban is more likely in the United States to be treated with suspicion (or even hate) and mistaken as Muslim than, say, an American white man wearing a baseball cap.[3] Consequently, the Sikh man likely knows more about racism, islamophobia, and microaggressions in the United States than the white man, who is less likely to experience them.

Box 7.1 Standpoint Theory and Positionalities

Which of the following questions can you readily answer? Which questions have never occurred to you before?

Which of the following questions can you readily answer? Which questions have never occurred to you before?

- Which buildings on your campus are easily accessible for people with physical disabilities?

- Which areas of campus are well lit at night and/or have safety call boxes?

- Where is the nearest gender-neutral bathroom located?

- Where are spaces available for religious practices?

- Who should you contact at your college for help paying for textbooks?

Your ability to answer likely depends on your physical ability, gender, religion (or lack thereof), and socioeconomic class. In other words, your knowledge (or ignorance) is influenced by your social identities.

Positionalities

Standpoint theory contends that we differ in our access to knowledge because our standpoints are differently positioned. Notice here the word positioned. That relates to the concept of a positionality, or a person’s location (or position) in relation to others in social categories of difference. Such social categories include ethnicity, gender, sexuality, physical ability, religion, citizenship, socioeconomic class, occupation, and so on. The American Sikh man and American white man, for example, have different positionalities regarding their ethnicity and religion. However, the men share the positionalities of nationality and gender.

A positionality, then, is largely the same as a social identity, but it recognizes that social identities typically carry and communicate cultural meanings through their distinctions from others within that category. In the social identity category of “physical ability,” someone who is physically able-bodied carries cultural associations that are different from those carried by someone who is visibly physically disabled, which differ from a person who is invisibly physically disabled.

Power

Different cultural meanings matter because they typically translate into differing degrees of societal power. In other words, a society will grant privileges to some positionalities within a social category. Physically able-bodied people, for example, appear regularly in visual media and school curricula, can expect most spaces and transportation to be designed for them, and are likely to be included in group activities. Cultures accord less privilege to others who differ within a category. Invisibly physically disabled people, for instance, are frequently hassled for using aids or needing extra help, since their need is not visibly obvious. Society oppresses and even denies others within a category. Visibly physically disabled people may have to research routes and spaces to ensure they can access them, are often mistaken as being mentally challenged or talked to like children, and face job discrimination.

To help articulate such differentiations, we can borrow from Toole the definitions of a dominantly situated positionality as “a knower that does not occupy a position of social oppression” (or one that enjoys social privilege and power) and a marginally situated positionality as “a knower that does occupy a position of oppression.”[4]

A notable irony is that cultural power is inversely related to knowledge.

| A dominantly situated positionality | A marginally situated positionality | |

| Examples | Physically able-bodied or white in the US | Visibly physically disabled or Sikh in the US |

| Cultural power | Granted more social power and privilege | Granted less social power and privilege |

| Knowledge | Likely knows less about oppression because they don’t likely experience it. | Likely knows more about oppressive systems and practices because they and their peers experience them. |

It is also important to note that while the terms “dominantly situated” and “marginally situated” imply two separate categories, you might think of positionalities instead as existing along scales of difference—from more dominantly situated to more marginally situated. For example, in terms of housing in the US, we might recognize homeowners as more dominantly situated than people who rent an apartment or home—and even then, we might differentiate among the types and neighborhoods of homes owned or rented. Shifting toward more marginally situated positionalities, we can identify people who are in temporary shelters (due to emergencies or personal safety) as less marginally situated than people who are homeless long-term.

In addition, it is important to state again that how a positionality is situated is based on social or cultural associations rather than anything inherent or true about the people who occupy it.

Box 7.2 Power and Oppression, Not Necessarily Majority and Minority

Labels for types of positionalities correspond with one’s position in relation to social oppression (and privilege). They do not necessarily equate to people in the majority or minority demographics of a population. We’ll provide two examples to explain.

Dominantly Situated but Not the Majority

A positionality is not dominantly situated because it is popular, common, or widespread. It is dominantly situated because it yields social power and privilege. Thus, a minority population can have a positionality that is dominantly situated. In South Africa between 1948 and 1994, for instance, the policy of apartheid gave white Afrikaners political, economic, and social power, though they were numerically in the minority compared to Black Africans.

Marginally Situated but Not the Minority

Similarly, a positionality is not marginally situated because it is uncommon or rare. Rather, it is marginally situated because it lacks societal power and suffers oppression. Thus, a majority population can have a positionality that is marginally situated. For example, being the only able-bodied person in a room full of people with physical disabilities does not make the able-bodied person marginally situated. They may be the only such person in that context, but culturally their physical ability still carries greater authority and privilege than people with disabilities. Most spaces, for instance, are designed for able-bodied people, implying they are “normal” compared to people with physical disabilities who are expected to adapt.

Of course, none of us consists of a single social identity or positionality, which is why we turn next to intersectionality.

Intersectionality and the Mythical Norm

Intersectionality is a concept coined in 1989 by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.[5] It suggests that our social identities consist of multiple features that combine in meaningful ways to create intersecting forms of privilege and oppression. Crenshaw uses the example of Black women to illustrate how they are more likely to experience the intersection of both racism and sexism, unlike white women (who encounter sexism) or Black men (who deal with racism).

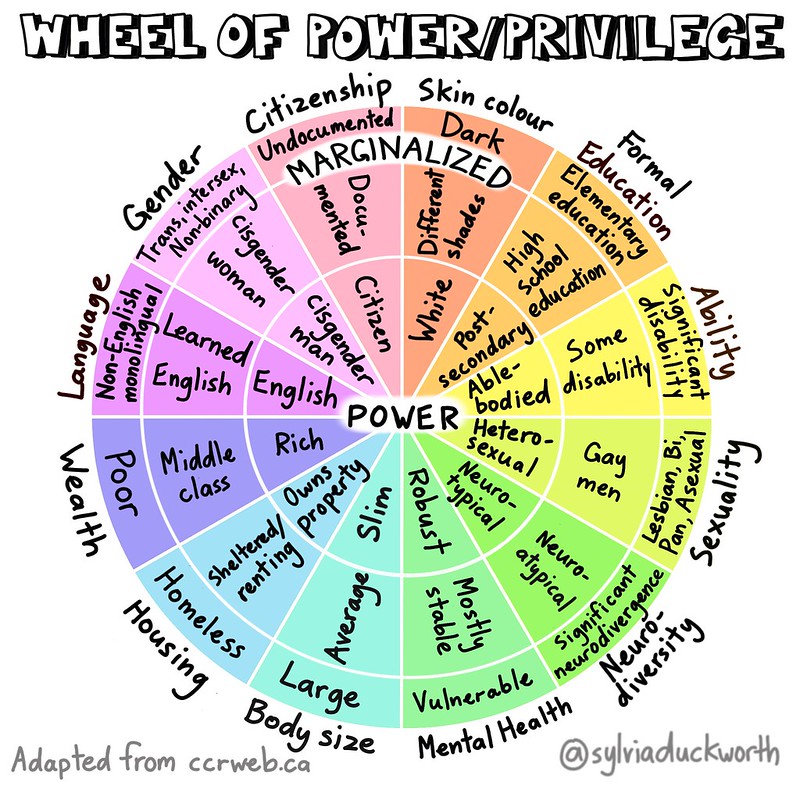

Each of us has developed a standpoint that consists of intersecting positionalities—some of which are more dominantly situated and some of which are more marginally situated. You can use the “wheel of power/privilege” to begin locating some of your positionalities and reflect on how they intersect and impact your experiences and knowledge.

You’ll notice that “power” is located at the wheel’s center. The closer one’s positionality approaches the center, the more social power, privilege, and prestige it is granted in the United States.

Positionalities near the center of power are also more likely to be associated with cultural norms. That is, they produce and reflect a culture’s standards or expectations for desirable (or normative) behaviors, values, and appearances. Having a driver’s license, for example, is expected and assumed as “normal” in the United States. That association contributes to its social power and privilege. Most of our transportation infrastructure is designed for car drivers, and a driver’s license is accepted for identification purposes when voting or buying alcohol, for instance.

Poet, professor, and activist Audre Lorde has labeled this phenomenon—what we might think of as the center of the intersectionality wheel—as the “mythical norm.” She explains, “In America, this norm is usually defined as white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure. It is with this mythical norm that the trappings of power reside within this society.”[6]

This norm is mythical because it is not actually normal or typical. Very few (if any) people occupy all the empowered social identities. Indeed, we are each unique. That means, of course, that the mythical norm does not necessarily correspond with the majority population. Rather, it consists of characteristics perceived as “normal” when, in fact, they are atypical! Nonetheless, we tend to use them to measure people against, including ourselves, because our culture deems them preferable. We might publicly downplay our differences from the mythical norm to appear “normal” or desirable.

The mythical norm helps explain why public discourse can be so difficult, especially when discussing social justice issues. Because dominantly situated positionalities typically avoid encounters with social oppression, they are more likely to discount or reject claims and evidence (by marginally situated positionalities) that social oppression exists.

Recall in chapter 4 that one reason social protest functions productively is because it can help people with privilege and power acknowledge societal inequity. However, that chapter also explains that social protest as a form of communication—often used by socially marginalized knowers—is typically critiqued as inappropriate, since it does not meet societal norms for civil discourse.

Standpoint and Ethical Rhetoric

Now that we’ve established standpoint theory, positionality, intersectionality, and the mythical norm, let’s return briefly to the three ethical considerations considered in the previous two chapters: speech preparation, speech performance, and listening.

Now that we’ve established standpoint theory, positionality, intersectionality, and the mythical norm, let’s return briefly to the three ethical considerations considered in the previous two chapters: speech preparation, speech performance, and listening.

Speech preparation: Part of being responsible to your audience—and doing the hard but often invisible work of speech preparation—is recognizing the opportunities and challenges posed by your standpoint for the speaking situation. Imagine you are speaking as a person with a marginally situated positionality about a topic to an audience with dominantly situated positionalities. Consider how sharing your experiences might offer the audience something important and meaningful. Your standpoint can help them recognize an issue that may seem obvious to you but not to them.

Of course, you must also anticipate that such an audience may resist your perspective and, accordingly, you should be prepared to address counterarguments and cite outside sources as well. On the flip side, if your audience or the speaking occasion seem odd or unfamiliar to you, perhaps because you and they occupy different social identities, treat the audience with respect. Learn as much as you can about them and the occasion and adjust your speech preparation accordingly.

Speech performance: Recall from chapter 5 that central to an ethical speech performance is using communication that, according to NCA’s credo, “enhances human worth, human life, and dignity.” Acknowledging your standpoint should help you recognize your assumptions about what topics are worth talking about, who is worth talking to, and how to address them. Becoming more cognizant and even critical of your assumptions may help you adopt the five ethical behaviors discussed in that chapter: avoiding plagiarism, conducting ethical research, practicing ethical and sound reasoning, using language carefully, and taking responsibility for the consequences of your rhetoric.

For instance, recognize that not everyone will be similarly impacted by your language and ideas. Research beyond your own standpoint to learn how people with marginally situated positionalities may be affected if your language and ideas are adopted. For example, if you advocate for an organization to move its meetings to a distant location, away from the “noise” of loud buses and “people on the street,” your speech will fail to account for the needs or humanity of people who rely on walking and public transportation.

Listening: Similarly, consider how your standpoint plays a role in who you listen to and how. Which speakers do you readily deem authoritative, and which might you be inclined to discount or dismiss? What kinds of people tend to speak in the communities you are a member of, and who must fight to be heard? Why?

If you become more aware of your standpoint, then you might choose to listen more attentively to people with different positionalities. Furthermore, you might recognize limits to your knowledge due to your dominantly situated positionalities and remain open to speakers who share different experiences.

Summary

This chapter explored standpoint theory and its implications for ethical speaking. Specifically, in this chapter we observed:

- Standpoint theory suggests that our positionalities influence what we believe to be true and normal.

- A positionality refers to a person’s location (or position) in relation to others in social categories of difference. Dominantly situated positionalities are those that occupy positions of privilege, while marginally situated positionalities occupy positions of oppression.

- Our social identities consist of multiple features that combine in meaningful ways to create intersecting forms of privilege and oppression.

- The mythical norm refers to the set of cultural expectations for what is normal and desirable. They are associated with dominantly situated positionalities. However, they are mythical because no one (or very few people) only consists of dominantly situated positionalities, and everyone is, in fact, unique.

- Knowing standpoint theory can help us reflect critically on our assumptions and think more deeply about the practices associated with ethical speech preparation, speech performance, and listening.

Key Terms

dominantly situated positionality

intersectionality

marginally situated positionality

mythical norm

positionality

standpoint theory

Review Questions

- What is standpoint theory?

- What does positionality refer to, and what are examples of positionalities?

- What do intersectionality and the mythical norm refer to?

- How can standpoint theory aid your speech preparation, speech performance, and listening?

Discussion Questions

- Identify several of your own positionalities, possibly by using the wheel provided earlier. Which positionalities were you born into, or which did you not choose? Which did you choose?

- What insights, lessons, or warnings have your positionalities enabled you to know that people who don’t share them might not?

- In your experience, what mythical norms are most frequently expected of speakers? Where/how are they expressed? What dominantly situated positionalities do the norms reflect? What happens when you violate them?

- Sandra Harding is credited with coining the term standpoint in Sandra Harding, Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women’s Lives (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991). ↵

- Alex Richardson, host and producer, Examining Ethics, “Identity Matters: Standpoint Epistemology with Briana Toole,” podcast, The Prindle Institute for Ethics, October 31, 2018, https://www.prindleinstitute.org/podcast/briana-toole/, archived at https://perma.cc/QJ8D-8ABE. ↵

- A. C. Thompson, “Sikhs in America: A History of Hate,” ProPublica, August 4, 2017, https://www.propublica.org/article/sikhs-in-america-hate-crime-victims-and-bias, archived at https://perma.cc/8PA6-D3PV. ↵

- Richardson, “Identity Matters" (emphasis added). ↵

- Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum (1989): 139–67, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf. ↵

- Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 116, https://www.socialism.com/drupal-6.8/sites/all/pdf/class/Lorde-Age%20Race%20Class%20and%20Sex.pdf, archived at https://perma.cc/EV9W-H9RA. ↵