31 Rhetorical Criticism: Context, Method, and Democratic Principles

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Identify a rhetorical artifact that addresses a substantive public matter.

- Reconstruct basic elements of a rhetorical artifact’s historical context.

- Evaluate a rhetorical artifact’s impact on democratic principles.

In the previous chapter, we defined rhetorical criticism as the description, interpretation, and evaluation of rhetoric to form judgments about its functions and consequences. We equipped you with basic instructions to conduct a rhetorical criticism: Describe a rhetorical artifact’s content, form, and absence, interpret its persuasive functions, and evaluate the functions and their consequences. We suggested that rhetorical criticism empowers you to account for an artifact’s symbolic action—the power of symbols to shape our thoughts, values, and actions.

In this chapter, we supplement those basic instructions with a richer understanding of how to select a rhetorical artifact, situate the artifact in a historical context, and evaluate it against democratic principles.

Selecting Rhetorical Artifacts

In chapter 30 we defined a rhetorical artifact as an object of study in rhetorical criticism. We explained that it is a specific instance of rhetoric that was produced for an audience at a particular time. Today, the range of potential rhetorical artifacts is limitless! That was not always the case.

In the early twentieth century: The modern field of rhetorical studies in the US was referred to as “speech” with a narrow focus on public, political speeches.

Since at least the 1960s: The range of rhetorical artifacts studied expanded to include literature, art, film, television, social movements, the internet, and social media.

As the examples in box 31.1 illustrate, today a rhetorical artifact can be anything from a billboard advertisement to a Taylor Swift song to a Disney film.

Consequently, we might expand our understanding of the rhetor, which we defined in chapter 1 as a person who speaks publicly, to the author or creator of the rhetorical artifact under examination. Thus, a rhetor may be a speaker, writer, lyricist, filmmaker, and so on.

Box 31.1 Rhetorical Artifacts

To help you appreciate the array of rhetorical artifacts available, read through this wide-ranging list of examples. Perhaps it will help you discover a type of artifact you’d like to analyze! This list is by no means comprehensive; it’s simply meant to spark your own ideas and discovery.

Artwork or photography

Billboard

Blog, editorial, or news column

Book or graphic novel

Commercial or marketing ad

Film

A particular space

Political declaration, manifesto, or campaign materials

Political or animated cartoon

Public address, lecture, or sermon

Social media post or meme

Social movement campaign materials

Song or music video

Statue or memorial

TV show

Video

Video game

Website

Choose a rhetorical artifact that meets the definition’s criteria and, for the purposes of this textbook, that addresses a substantive public matter. First, the artifact must be a specific instance of rhetoric that a rhetor (speaker, writer, etc.) produced for an audience at a particular time. That is what makes a rhetorical artifact different from a topic or subject. Use the following table to better distinguish between rhetorical artifacts and topics.

|

Topics |

Rhetorical Artifacts |

|

Mental health |

A YouTube video devoted to talking about mental health A clothing campaign that emphasizes mental health messages Pamphlets produced by your college’s health and wellness office |

|

Christianity |

A sermon delivered by a pastor A music video by a Christian artist An altar inside a church building |

Second, ideally choose a rhetorical artifact that addresses a significant community concern or problem. In other words, locate an artifact that engages a social, political, or financial issue that a community cares about and that carries notable implications for that community’s welfare. Find a rhetorical artifact that attempts to influence how audiences view or act on that issue. Don’t assume that only serious rhetorical artifacts qualify. An advertisement, a video game, or even a sports team mascot might be eligible if, for example, it engages a political issue or communicates a social message about gender, race, religion, and so on. If you’re unsure if an artifact addresses a substantive public matter, ask your instructor for help.

Situating Rhetorical Artifacts in Historical Context

In addition to selecting an appropriate rhetorical artifact, you also need to situate that artifact in a historical context. Context refers to the conditions or situation within which rhetoric is produced. Critics are typically less concerned with a rhetorical artifact’s lasting or enduring beauty and much more interested in its relationship with its particular context.

The Reciprocal Relationship of Artifacts and Contexts

The Reciprocal Relationship of Artifacts and Contexts

All rhetorical acts take place in a historical context of some type—be that a particular social context, financial context, legal context, and so forth. That context influences the rhetorical artifact’s nature, content, functions, and goals. For instance, consider the following example:

|

Context |

|

Rhetorical Artifact |

|

The ongoing Civil War, the setting of a battlefield, and the occasion of a dedication ceremony for the National Cemetery of Gettysburg |

influenced ⇒ |

the content and form of President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. |

The relationship between an artifact and its context is reciprocal, however. Just as contexts influence rhetoric, rhetors produce artifacts to influence the context! A rhetor may hope to move an audience to improve a community problem, buoy a person into leadership, or strengthen community relationships. Let’s return to the previous example:

|

Rhetorical Artifact |

|

Context |

|

Lincoln used his Gettysburg Address |

to influence ⇒ |

Americans to end the Civil War and reunite as a nation. |

Thus, just as the context shapes the artifact, so too the artifact attempts to influence the context.

Determining an Artifact’s Historical Context: Six Questions to Answer

To determine an artifact’s historical context, answer who, why, what, to whom, when, and where surrounding the rhetoric’s production. Use the prompting questions in box 31.2 and the example in box 31.3 for help.

Box 31.2 Reconstructing the Historical Context

- Who: Who was the rhetor? What might audiences have already known about them?

- Why: What seemed to prompt this rhetoric? What was the rhetor’s goal?

- What: What type of artifact are you analyzing? What are its major characteristics?

- To Whom: Who were the direct, target, implied, and implicated audiences for the artifact?

- When: When was the artifact produced, delivered, aired, or uploaded? What was the specific date? What might be useful to know about the time period in which it appeared?

- Where: Where was the artifact delivered, consumed, or uploaded? Name the medium it used and the physical location or the technological platform employed (YouTube, Snapchat, etc.).

Box 31.3 An Example of Establishing the Historical Context

In the previous chapter, we introduced the National Debt Clock that hangs outdoors in New York City. We used it to exemplify how you might describe, interpret, and evaluate a rhetorical artifact. What is its historical context? Based on our research, we discovered the following:

- Who: The clock was originally designed by New York real estate developer Seymour Durst, who worried about the ramifications of governmental debt.[1]

- To whom: See box 31.4.

- Why: According to The New York Times, Durst “wanted a vivid way to show Americans how big the national debt was, and also to nudge elected officials to do something about it.”

- What: The display is an eleven-by-twenty-six-foot billboard with static (unchanging) words and digitally displayed numbers that continually change to reflect the US gross national debt and each American family’s share moment to moment. It is more widely referred to as the “National Debt Clock.”

- When: The display was installed in 1989 after two terms by President Ronald Reagan, under whose administration the national debt nearly tripled to $2.6 trillion.[3] During the early to mid-1990s, because the national debt decreased under President Clinton’s administration, the clock’s total went down. In the late 1990s, the clock’s total went up again as President George Bush Sr. increased the national debt. The clock continues to run today along with a virtual edition.[4]

- Where: The billboard was originally hung on the side of a Manhattan building on Sixth Avenue between Forty-Second and Forty-Third Streets, just one block away from Times Square. It moved in 2004 but was repositioned near its original spot in 2017.

Notice how learning about the display’s historical context enriches our understanding of the reciprocal relationship between a rhetorical artifact and its context. The context prompted the clock’s production (as a response to the national debt tripling), and the clock attempted to influence that context (hoping to prompt legislators to lower the national debt).

Take special care when identifying the audience (“to whom”) for your rhetorical artifact. Rhetoric creates meaning in relation to audiences; it is they who respond to, endorse, or reject a message.

Take special care when identifying the audience (“to whom”) for your rhetorical artifact. Rhetoric creates meaning in relation to audiences; it is they who respond to, endorse, or reject a message.

To determine audiences, let’s return to the ways we conceived of them in chapter 10. Namely, we differentiated among the direct, target, implied, and implicated audiences. Recall the following:

- The direct audience refers to the people who are exposed to and attend to the rhetoric.

- The target audience consists of specific members who are more likely to be influenced by the appeals and/or more likely to act on them.

- The implied audiences are the groups represented in the message.

- The implicated audiences refer to the groups affected by the message if it is successful.

Knowing who interacted with, was targeted by, was referenced in, or was potentially impacted by the artifact can help you make more specific arguments about how the artifact functioned. See box 31.4 for an example.

Box 31.4 An Example of Identifying Audiences (“To Whom”)

Let’s return to the National Debt Clock to discuss why identifying an artifact’s audience can aid your rhetorical analysis. The clock’s audiences included the following:

- Direct audience: For the National Debt Clock, the direct audience includes everyone who walks by and notices the clock, which likely consists of local residents, tourists, and nearly business workers and customers.

- Target audience: Based on Durst’s original goal, the target audience was—and likely remains—elected officials who can lower the debt as well as Americans who can pressure their officials to do so.

- Implied audiences: Clearly Americans, particularly American families, are referenced by the billboard through the use of “our” and “your family share.”

- Implicated audiences: Americans are among those affected by national debt, particularly when that debt exceeds the limit authorized by Congress. When exceedance approaches, Congress historically has voted to raise the debt limit to avoid defaulting on the nation’s legal financial obligations. A default would send the economy into a recession, affecting not only families but also employers and a wide host of industries.[5] But even when default is avoided, elected leaders and their constituents are impacted every time the debt approaches exceedance. Republican and Democrat leaders negotiate (often aggressively) before they agree to vote to raise the limit, which can be stressful for all as the fear of default looms.

While the national debt display likely grabs the attention and concerns of the direct audience who walk past it, it may fail to adequately move the Americans—who are the clock’s target, implied, and implicated audiences—to action. American families likely feel inadequate to slow or stop the looming and constantly increasing numbers, especially given the rancor between political parties every time leaders need to raise the debt limit. The sign, consequently, may amplify feelings of doom and powerlessness more so than encourage Americans or officials to decrease the national debt.

Box 31.5 Researching the Historical Context

How can you learn about an artifact’s historical context? Look for answers to the six contextual questions in such sources as the following:

- Reliable news sources: Check for news stories about the artifact, the rhetor, or the occasion.

- Opinion sources (blogs, editorials, social media posts, polls, etc.): Discover what some audiences knew about the rhetor, what they expected from the rhetoric, and/or how they reacted to the artifact.

- Books: Find a biography about the rhetor or a book about the time period or occasion.

- Scholarly articles: Discover what scholars have claimed about the rhetor, artifact, or similar types of artifacts.

- Military or government websites: If appropriate, discover information about the rhetor and relevant military or political efforts.

You can also research references made or names mentioned in the artifact.

Make sure to review chapters 8 and 9 for guidance on researching effectively.

Every rhetorical artifact takes place in a historical context. Understanding that context provides important insights into the rhetoric’s functions.

Using a Rhetorical Method

Once you have identified a particular rhetorical artifact and researched its context, you must determine the most appropriate way to conduct your analysis. Often this means making use of a particular method. A rhetorical method is a perspective, approach, or orientation for analyzing an artifact.

Each method focuses your attention on some elements of rhetoric and, thus, away from other elements. For example, within rhetorical studies there are methods that focus on metaphors, myths, and gender depictions, among many others. As each name suggests, the method directs your attention to the use and function of certain elements in an artifact. In the chapters that conclude this textbook, we discuss two methods for analyzing rhetoric for democracy and civic engagement: public communication analysis (chapters 32 and 33) and ideological criticism (chapters 34 and 35).

Each method focuses your attention on some elements of rhetoric and, thus, away from other elements. For example, within rhetorical studies there are methods that focus on metaphors, myths, and gender depictions, among many others. As each name suggests, the method directs your attention to the use and function of certain elements in an artifact. In the chapters that conclude this textbook, we discuss two methods for analyzing rhetoric for democracy and civic engagement: public communication analysis (chapters 32 and 33) and ideological criticism (chapters 34 and 35).

Box 31.6 Rhetorical Methods as Lenses

To better understand how rhetorical methods work, think about when you get an eye exam by an optometrist.

Often in that setting, the optometrist checks your eyes to determine whether you need correction (through glasses or contact lenses). They place a series of lenses in front of your eyes as you look at the eye chart. If the optometrist has correctly measured your eyes and selected the right lenses, what was blurry comes into clear focus. The lenses change what you can see.

A rhetorical method is like using a powerful lens that focuses your attention and shapes your vision, resulting in new insights about an artifact. Different methods, like different lenses, change what you see. When done well, rhetorical methods help you provide profound insights into human communication.

Evaluating an Artifact’s Impact on Democratic Principles

In the previous chapter, we named evaluation as the final step of the rhetorical criticism process. We explained that evaluation involves making judgments about the functions and consequences of the rhetoric examined. We suggested evaluations can help us see an aspect of our society we had not seen clearly before, teach us something about a particular group we had not known about or paid close attention to, or even reveal a particular rhetoric’s potential dangers or benefits on those who experience it.

Here we add that your evaluation of an artifact can—and should—also judge how the rhetorical artifact impacts our democracy. By explicitly attending to this impact, you will strengthen the civic engagement function of your rhetorical criticism. To explain, we’ll first recognize the power of rhetoric on democracy and then provide guidance for evaluating artifacts accordingly.

Rhetoric, Democracy, and Demagoguery

We believe rhetoric that addresses public affairs should strengthen democracy. This position—that great rhetoric aids democracy—has long been held by many Americans. In 1948, for instance, communication scholar Earnest Brandenburg noted,

Every orator of sufficient prominence to be considered in the area of Statecraft has been a champion of democracy and the will of the people. Or, to state it another way, rhetorical critics and historians have seemed to decree that prominence be accorded to those who have championed democracy.[6]

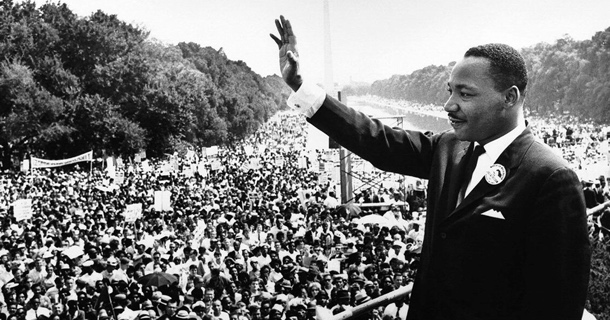

This commitment to speech that strengthens democracy held true in the early twenty-first century when rhetoric scholars Stephen Lucas and Martin Medhurst listed the top 100 speeches in that century. Most on the list, from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech to John Kerry’s 1971 speech against the Vietnam War, clearly advocated democratic ideals.[7]

In contrast, notoriety accrues to rhetors who place their personal gain over democracy. Some speakers, for example, have practiced demagoguery, which is a rhetoric that explicitly claims to speak for the public’s best interests but implicitly gains more political power for the speaker and exacerbates divisions among the public, thereby weakening democracy. People who employ demagoguery are called demagogues. Their discourse typically overly relies on emotional appeals (especially fear and hatred), exaggeration, and divisiveness to encourage listeners to blame others for their problems and to act before thinking through a matter. Demagoguery, such as in Senator Huey Long’s 1934 speech “Every Man a King” and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s 1950 speech “Enemies from Within,” are considered important speeches but never great because of the ways they undermined and ultimately weakened democracy.

Evaluating an Artifact’s Impact on Democracy

How do you decide if an artifact strengthened or weakened democracy? You should attend to the principles upon which democracy depends or, as rhetoric scholar Lloyd Bitzer states, the “higher principles of art, those that separate genuine public communication from propaganda, deception, power wielding, or self-aggrandizement.”[8]

Democratic principles are the behavioral standards necessary for democratic governance to exist and thrive. Such principles include but are not limited to those outlined in box 31.7. Artifacts that prioritize, reinforce, and/or practice such principles strengthen democracy. Artifacts that discount, weaken, and/or violate them weaken democracy.

Box 31.7 Democratic Principles

- participation of ordinary people in civic affairs

- equality of all people (giving all people the ability to participate in civic affairs rather than discriminating based on race, religion, sexuality, etc.)

- tolerance of, and protection for, a variety of voices, including minorities or those with minority opinions

- open and thoughtful engagement of public issues, arguments, and positions

- freedom of the press to independently report on civic affairs, public leaders, and elected officials

- unity or shared identity of community members as the public or as “we the people”

- accountability of officials and public leaders to the will of the people

- transparency in civic affairs so the public knows what officials and leaders are discussing or deciding and why

- responsible and ethical use of power rather than using power for corrupt ends

- respect for, and protection of, the basic human rights of all people, including freedom of speech and the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness

- fair rule of law (everyone, including leaders, is subject to prosecution if they violate the law, and the law is fairly applied)

Considerations When Evaluating an Artifact’s Impact on Democracy

As you decide how a rhetorical artifact impacts democratic principles, keep four considerations in mind: Consider the artifact’s historical context, recognize that a rhetorical artifact can aid democratic principles while forwarding an ideology with which you disagree, be aware that the rhetor’s conscious motive should not dictate your evaluation of an artifact’s impact on democratic principles, and realize the success of a rhetorical artifact may not necessarily correspond with its impact on democracy. Let’s briefly explore each of these considerations.

As you decide how a rhetorical artifact impacts democratic principles, keep four considerations in mind: Consider the artifact’s historical context, recognize that a rhetorical artifact can aid democratic principles while forwarding an ideology with which you disagree, be aware that the rhetor’s conscious motive should not dictate your evaluation of an artifact’s impact on democratic principles, and realize the success of a rhetorical artifact may not necessarily correspond with its impact on democracy. Let’s briefly explore each of these considerations.

Box 31.8 Evaluating a Rhetorical Artifact’s Impact on Democracy

When evaluating a rhetorical artifact’s impact on democracy, keep four considerations in mind:

- The artifact reacts to and impacts a specific historical context—that is, a specific community at a particular place and time.

- A rhetorical artifact can aid democratic principles while forwarding an ideology with which you disagree.

- The rhetor’s conscious motive should not dictate your evaluation of an artifact’s impact on democratic principles.

- The success of a rhetorical artifact may not necessarily correspond with its impact on democracy.

Consider the Artifact’s Historical Context

First, consider the artifact’s historical context when judging its impact on democratic principles. The artifact was created at a specific moment for a particular audience or set of audiences. Rather than ask if the text strengthens or weakens democracy in a general sense, you need to more specifically ask whether and how it aided or hampered these democratic principles for this community at this place and time in relation to this issue.

Do Not Simply React to the Ideology Advanced by the Artifact

Second, a rhetorical artifact can aid democratic principles while forwarding an ideology with which you disagree. In fact, the inclusion of diverse perspectives and the tolerance for disagreement are two hallmarks of democracy. Demagoguery can become an overly used accusation to silence those with whom we disagree. A person’s political stance, background, and vision do not necessarily make their rhetoric demagogic; rather, their expression, proposals, and appeals determine whether their rhetoric harms or aids democratic principles.

Thus, we need rhetorical critics who can carefully examine specific examples of rhetoric to determine how they are functioning. If we don’t have these critics at work, we risk a cynical public who believes all politicians or public figures receive (and deserve) the same types of disparagement.

Motive Is Insufficient

Third, the rhetor’s conscious motive should not dictate your evaluation of an artifact’s impact on democratic principles. Senator Joseph McCarthy may have truly believed he was saving the United States from a communist takeover even as his speeches undermined democratic ideals by silencing dissent, creating division among Americans, and securing greater authority for himself. Alternatively, a rhetor may appear to be aiming to hurt American democracy, perhaps by aggressively critiquing the country, while their rhetoric actually strengthens democratic principles by pointing out violations.

Democratic Impact May Differ from Success

Fourth, the success of a rhetorical artifact may not necessarily correspond with its impact on democracy. It is possible that a rhetor might accomplish their goals but weaken democracy or vice versa. Box 31.9 offers an example.

Box 31.9 Evaluating the National Debt Clock

The case of the National Debt Clock offers an example of an artifact that failed to reach the desired objective but still reinforced a fundamental democratic value.

- Durst failed in using the clock to pressure lawmakers to lower the debt, given that it has increased from $2.9 billion in 1989 when the display was erected to over $30 trillion in the 2020s.

- However, the clock encouraged—and continues to encourage—ordinary citizens to get involved in civic affairs. It prompts us to pay attention to and question the debt amount.

Summary

This chapter provided additional tools to conduct an insightful and productive analysis of public communication. They included the following:

- Any rhetorical criticism begins by selecting a rhetorical artifact, which functions as the object of study.

- All rhetorical criticism situates the rhetorical artifact within its historical context, which refers to the conditions or situation within which rhetoric was produced. It addresses who, to whom, what, when, where, and why surrounding the production of the rhetoric.

- Rhetorical critics often use a rhetorical method to guide their analysis.

- Critics best use rhetorical criticism as a form of democratic participation when they explicitly focus attention on how rhetorical artifacts impact democratic principles.

Key Terms

context

demagogue

demagoguery

democratic principles

rhetorical method

Review Questions

- What criteria should a rhetorical artifact meet?

- What six aspects of an artifact’s historical context should a critic research?

- What does it mean to evaluate a rhetorical artifact’s impact on democracy?

Discussion Questions

- What are specific examples of rhetorical artifacts that address substantive civic issues and meet the definition’s criteria?

- How do you know when you have discovered enough historical contextual information? Not enough?

- Should you evaluate an artifact’s impact on democratic principles if it was produced in a country with a different form of governance? Why or why not?

- Eun Lee Koh, “Following Up; Time’s Hands Go Back on National Debt Clock,” New York Times, August 13, 2000, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/08/13/nyregion/following-up-time-s-hands-go-back-on-national-debt-clock.html. ↵

- Koh, “Following Up.” ↵

- Lou Cannon, “Ronald Reagan: Domestic Affairs,” Miller Center, August 28, 2023, https://millercenter.org/president/reagan/domestic-affairs, archived at https://perma.cc/8NPG-F6R2. ↵

- Koh, “Following Up.” A running total of the US national gross debt is available at “U.S. National Debt Clock: Real Time,” U.S. Debt Clock.org, https://usdebtclock.org/, archived at https://perma.cc/T5M7-G67E. ↵

- “Debt Limit,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, accessed June 27, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/. ↵

- Earnest Brandenburg, “Quintilian and the Good Orator,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 34 (1948): 28. ↵

- Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst, eds., Words of a Century: The Top American Speeches, 1900–1999 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), xi–xiii. ↵

- Lloyd F. Bitzer, “Rhetorical Public Communication,” Critical Studies in Mass Communications 4, no. 4 (1987): 426. ↵