30 Rhetorical Criticism as Civic Engagement

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Describe rhetoric as symbolic action.

- Complete the descriptive, interpretive, and evaluative steps of rhetorical criticism.

- Demonstrate five mentalities through their rhetorical criticism.

To this point in the textbook, our attention has focused on aiding your civic engagement through the creation and facilitation of speech. That is, we have primarily concentrated on producing your own rhetoric.

We now turn to rhetorical criticism to closely examine other rhetors’ messages. Rhetorical criticism (or its synonym, rhetorical analysis) is the description, interpretation, and evaluation of rhetoric to form judgments about its functions and consequences. In other words, rhetorical criticism equips us to investigate the rhetorical choices other people make.

We now turn to rhetorical criticism to closely examine other rhetors’ messages. Rhetorical criticism (or its synonym, rhetorical analysis) is the description, interpretation, and evaluation of rhetoric to form judgments about its functions and consequences. In other words, rhetorical criticism equips us to investigate the rhetorical choices other people make.

Rhetorical criticism functions as a form of civic engagement. Through rhetorical criticism, we become better, more knowledgeable consumers of public information. In other words, we notice persuasive appeals in the messages that bombard us daily and think more deeply about their implications. We can use this knowledge to educate fellow community members. Such insights help us hold officials and speakers accountable, weigh policy options, and lend support for, or voice resistance to, plans and proposals. In sum, rhetorical criticism enables democratic participants to improve both our understanding of public communication and the decisions made by our communities.

In this chapter we first describe rhetoric as symbolic action. We then explain the goal and steps of rhetorical criticism, which helps illuminate a rhetoric’s symbolic action. We end by describing rhetorical criticism as an intellectual discipline for which critics should adopt specific mentalities.

Rhetoric as Symbolic Action

In chapter 1, we defined rhetoric as a civic art devoted to the ethical study and use of symbols (verbal and nonverbal) to address public issues. Let’s consider what we mean by “symbols.” A symbol is something that expresses an idea or refers to something beyond itself. Our definition of rhetoric references verbal symbols (language, our words) and nonverbal symbols (facial expression, body language, etc.). Symbols can also be visual (images, graphics, signs, etc.) or audio (sounds, beats, etc.).

In this chapter we examine the use of symbols more closely to see how they act and what they accomplish. We take as our guiding inspiration the conception of rhetoric as symbolic action, which comes from the most influential rhetorical scholar of the twentieth century, Kenneth Burke. Burke contended that we see and understand our world and ourselves through the medium of symbols.

Symbolic action refers to the power of symbols to do things—that is, to shape our thoughts, values, and actions. As Burke explains, our words (as verbal symbols) are simultaneously reflections, selections, and deflections of reality:

Symbolic action refers to the power of symbols to do things—that is, to shape our thoughts, values, and actions. As Burke explains, our words (as verbal symbols) are simultaneously reflections, selections, and deflections of reality:

- Words offer a reflection of reality—that is, they can be used to describe everyday situations, human society, our world, and the universe.

- Words offer a selection of reality because we can never describe everything about something or all the angles or perspectives that can be taken on it. Thus, all descriptions are incomplete selections of reality.

- Finally, words provide us with a deflection of reality in that all descriptions focus our attention on certain aspects and take our attention away from others.[1]

As a high school student, for example, you may have made plans to hold an event at your house while your parents were away. When you invited your friends, you might have described the event as a “party.” This term reflected the event and selected the fun and possibly raucous aspects of the event to excite your friends to attend. However, when you described the event to your parents to gain their permission, you may have called it a “get-together” or “hangout.” Those terms also reflected the event. But they deflected your parents’ attention away from its possible raucousness and, instead, selected its social nature to focus upon.

We make language choices—as well as choices with our nonverbal, visual, and audio symbol use—because we recognize that symbols do something. Through selection and deflection, they shape the way we see and understand the world. You might even say they constitute our reality; that is, our symbols compose the world we know and act within.

Box 30.1 Symbolic Action in Practice

Imagine you are driving and hit another car. No one is hurt, but both vehicles are damaged, and the incident is reported to the police.

- When you call your automobile insurance agent about the incident, you probably want to minimize what happened so your insurance rate does not increase. What do you call the incident? A “fender-bender”? A “bump”?

- When you call your significant other to tell them what happened, you may want to amplify what happened to gain their sympathy. What do you call the incident for them? Perhaps a “crash” or “collision”?

- Who else might you talk to about the incident, and what alternative words might you use to differently influence their perceptions of it?

Consider: What does each label deflect listeners’ attention away from? What aspects of the event do each of the words select for listeners to focus on?

Rhetorical Criticism

If symbols function persuasively, then how can you best study this symbolic action? Rhetorical criticism is designed to do just that! As we defined earlier, rhetorical criticism is the description, interpretation, and evaluation of rhetoric to form judgments about its functions and consequences.

Though it’s easy to confuse “criticism” with complaint or fault finding, in rhetorical criticism, the word refers simply to analysis and study.

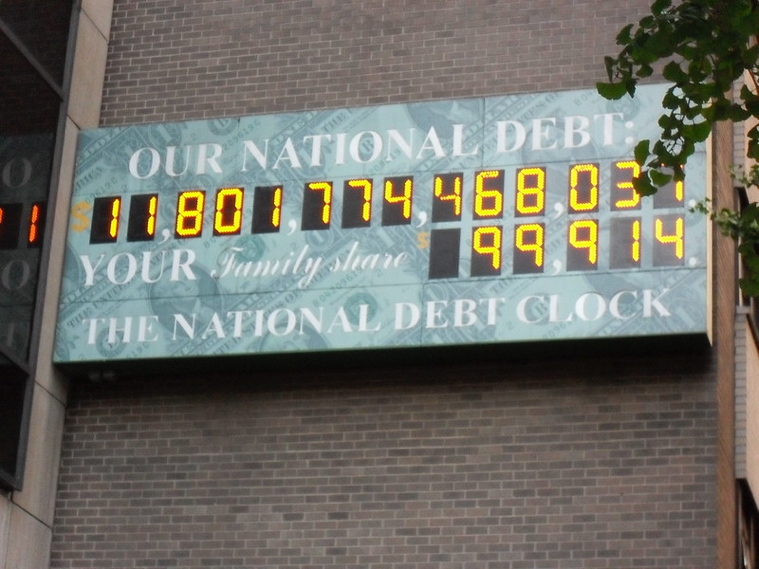

Through rhetorical criticism, we study how rhetoric—be it verbal, textual, visual, or material—acts persuasively. More specifically, we study how rhetoric functions through artifacts. A rhetorical artifact is an object of study in rhetorical criticism. By “object,” we mean a specific instance of rhetoric that was produced for an audience at a particular time. A rhetorical artifact is the focal point of analysis. Box 30.3 discusses the National Debt Clock as a sample rhetorical artifact. In the next chapter, we provide guidance for selecting a rhetorical artifact to analyze.

The rhetorical critic, or person conducting the rhetorical criticism, seeks to understand how the artifact functions persuasively:

- How does the artifact create meaning for audiences?

- How does it invite audiences to perceive reality?

- How does the artifact attempt to persuade audiences?

When we say “audiences” in rhetorical criticism, we typically include an artifact’s direct audience. As described in chapter 10, a direct audience consists of the people who are exposed to and attend to a speech—or, in this case, the artifact. However, we keep “audiences” plural, because a critic may want to differentiate how an artifact functioned persuasively for various types of audiences discussed in chapter 10: a target audience (those most likely to be influenced by, or to act upon, the message), an implied audience (those represented in the artifact), and/or an implicated audience (those impacted by the artifact if its persuasion is successful).

As a rhetorical critic, you will seek to discover how an artifact functions persuasively for audiences. To do so, you will analyze a rhetorical artifact in a thoughtful and systematic manner, following three basic steps: description, interpretation, and evaluation.

Description

In rhetorical criticism, description involves noticing, identifying, and explaining a rhetorical artifact’s content, form, and absence. In terms of rhetorical content, you examine the message or argument(s) that the artifact advances and the appeals used to do so. You ask what the rhetoric is claiming, conveying, or implying, and you try to provide specific answers.

In rhetorical criticism, description involves noticing, identifying, and explaining a rhetorical artifact’s content, form, and absence. In terms of rhetorical content, you examine the message or argument(s) that the artifact advances and the appeals used to do so. You ask what the rhetoric is claiming, conveying, or implying, and you try to provide specific answers.

Rhetorical analysis also investigates the form that rhetoric takes. The form includes but is not limited to symbol type (verbal, nonverbal, visual, audio), organization, style, medium, and genre. For instance, it is one thing for an environmental activist to publish an editorial in the newspaper about fossil fuels, and it’s another for the same activist to deface a museum or historical painting. In both cases the point being made—expressing opposition to climate change—is the same, but differences in protest forms likely produce differing reactions and understanding. Consequently, it’s important for you to describe not just the content but also the form of the rhetoric being analyzed.

Finally, you may also describe anything significant the artifact leaves out. When describing a political advertisement that quotes an opposing candidate, for instance, it may be important to note if the quotation was cut off early or made more sense when the comments just before it are included. Sometimes absence can be as important to notice and describe as presence.

For your rhetorical criticism, use the prompts in box 30.2 and the example in box 30.3 for guidance and help with description.

Box 30.2 Describing a Rhetorical Artifact

- Content: What is the artifact’s primary message, claim, or point? Does it communicate that message explicitly or implicitly? What types of appeals does it use to communicate (logos, pathos, ethos)?

- Form: What types of symbols does the artifact utilize (verbal, nonverbal, visual, audio)? How might you characterize the artifact’s style? How is it organized or arranged? What medium or genre does it use?

- Absence: What does the artifact exclude or overlook that is significant?

Box 30.3 Describing the National Debt Clock

We engage in description regularly as we encounter messages of all types. For example, imagine you are visiting New York City, and as you walk near Times Square, you come upon the following large display:

If you were on your cell phone with a friend at this moment and wished to describe it to them, you might start by saying something like, “I am looking way up at a huge sign that says, ‘Our National Debt.’ It has a digital counter that keeps changing by increasing the dollar amount. It shows how much the national debt is growing and how much each family in America owes. It doesn’t indicate, though, if the national debt has ever decreased.”

That is description because it explains what you have observed about the sign’s content (message), form (huge sign, changing digital counter, word choice), and absence (any historical decrease in the national debt).

Notice, too, that the display qualifies as a rhetorical artifact. It is the object (focus) of our analysis, and it is a specific instance of rhetoric that was produced for an audience at a particular time.

Interpretation

Interpretation is the second step in rhetorical criticism, though it often closely accompanies description. Interpretation involves making inferences about how an artifact’s content, form, and absence function persuasively.

Returning to the notion of symbolic action discussed earlier, you make interpretations by asking, “What’s that doing?” where “that” refers to the elements you described. For instance, how do pathos appeals invite the direct audience to perceive the situation? What do they emphasize? What does the artifact’s organizational structure deflect the audience’s attention away from? How might the artifact’s absence of conflicting perspectives narrow the audience’s memory of the topic or event? Your answers should use active verbs to accentuate the symbolic action. If you are not using verbs when interpreting a rhetorical artifact, then you are probably describing rather than interpreting its persuasive functions or symbolic action.

The prompts in box 30.4 and the example in box 30.5 give you further support and help with interpretation.

Box 30.4 Interpreting a Rhetorical Artifact

- How do the rhetorical artifact’s content, form, and absence attempt to influence audiences’ perceptions, values, or actions?

- What do the rhetorical artifact’s elements emphasize or draw attention to?

- What do the rhetorical artifact’s elements deflect attention away from?

Use active verbs when answering these questions to accentuate the artifact’s symbolic action.

Box 30.5 Interpreting the National Debt Clock

Let’s return to the phone conversation (started in box 30.3) with your friend about the National Debt Clock that hangs in New York City.

Fairly quickly after describing the clock, you would likely move to interpreting how its content, form, and absence function persuasively. You might exclaim the following:

- Form: “Wow, the size and height of that huge sign convey the enormity of the debt!”

- Content: “The use of the word ‘our’ on that sign drives home the shared burden all Americans have and stokes fears that we cannot pay it off.”

- Absence: “But by not showing if or how the debt has decreased in the past, the sign implies it has only steadily grown.”

Those are interpretations because they infer how the content, form, and absence are functioning persuasively. Notice that active verbs (“convey,” “drives home,” “stokes,” “implies”) capture the sign’s symbolic action.

Evaluation

We clarified earlier that “criticism” in rhetorical criticism does not mean complaining or fault finding. However, rhetorical analysis does include evaluation.

Evaluation in rhetorical criticism involves making judgments about the functions and consequences of the rhetoric examined. Judgments are based on the artifact’s rhetorical features: what they are (description) and how they function persuasively (interpretation) in the context. Evaluations are not about, nor based on, the critic’s feelings about the artifact. Box 30.6 provides an example to make this distinction clear.

Evaluation in rhetorical criticism involves making judgments about the functions and consequences of the rhetoric examined. Judgments are based on the artifact’s rhetorical features: what they are (description) and how they function persuasively (interpretation) in the context. Evaluations are not about, nor based on, the critic’s feelings about the artifact. Box 30.6 provides an example to make this distinction clear.

Box 30.6 Evaluating the National Debt Clock

To clarify appropriate from inappropriate evaluations for rhetorical criticism, let’s return to the National Debt Clock example we considered in boxes 30.3 and 30.5. Imagine what else you might say to your friend about the sign:

|

Not Appropriate Evaluations for Rhetorical Criticism |

Appropriate Evaluations for Rhetorical Criticism |

|

“That sign is ugly and old looking. I prefer newer billboards with sharp LED lights.” |

“That’s a helpful sign because it reminds Americans what is happening every day, which is that each and every one of us is going further and further into debt!” |

|

“Thinking about the national debt stresses me out. I don’t need to be reminded about that when I’m just trying to sightsee. It’s unfair to put that sign here.” |

“That sign is misleading because it makes increased debt seem unstoppable when some past presidents have played a role in successfully decreasing it.” |

|

These are not appropriate evaluations. Although they make judgments (“ugly,” “unfair”), they focus more on the critic’s preferences and feelings (“I prefer,” “stressed me out”) as support than on the consequences of the artifact’s rhetorical elements. |

These are appropriate evaluations because they make judgments (“helpful,” “misleading”) about the ethical and pragmatic consequences of the artifact’s rhetorical elements. |

You might wonder why rhetorical critics judge an artifact’s functions and consequences. Typically, such evaluations teach us about ourselves, a particular group, or a specific rhetorical artifact.

The evaluation generated by rhetorical criticism can help us see an aspect of our society we had not seen clearly before. For instance, rhetoric scholar Michael Butterworth analyzed how the continued regular performance of “God Bless America” at sporting events since 9/11 promotes nationalistic thinking that places sport in the service of US militarism. In doing so, Butterworth helped us see deeper meaning in what we might otherwise consider a harmless and even soothing ritual.[2]

Other times the evaluation teaches us something about a particular group we had not known about or paid close attention to. Examples include analysis that provides insight into the rhetoric of political and social movements ranging from Moms for Liberty to Black Lives Matter advocates. Here evaluation highlights the implications and ethics of tactics designed to move audiences and generate support for a cause.

Sometimes the evaluation teaches us about a particular rhetorical artifact’s potential dangers or benefits on the beliefs, attitudes, and courses of action of those who experience it. This might range from a critic judging what they perceive to be the damaging gender stereotypes promoted in some Disney films to valorizing the depiction of superheroes, such as Captain America, as embodying cherished values including freedom, equality, justice, and courage.[3] Evaluation is the most complex and significant component of rhetorical criticism.

Box 30.7 Evaluating a Rhetorical Artifact

- How does your rhetorical criticism help us notice and understand an aspect of our society we had not clearly seen before?

- What might your analysis teach us about a particular group, individual, organization, company, or institution?

- What can your rhetorical criticism illuminate about the dangers or benefits of a particular rhetorical artifact’s potential impacts on audiences’ beliefs, attitudes, or courses of action?

In sum, rhetorical criticism carefully investigates the symbolic action by a rhetorical artifact through the steps of description, interpretation, and evaluation. It is both a practice and an intellectual discipline, which we will consider next.

Rhetorical Criticism as an Intellectual Discipline

How do you know when your rhetorical criticism—following the steps of description, interpretation, and evaluation—has led you to the right answer? How do you know if your conclusions about a rhetorical artifact are correct? To answer, we need to characterize the discipline of rhetorical criticism. As we will explain, it is a systematic and reasonable as well as a creative and manifold field of study. And it requires critics to adopt a set of specific mentalities.

Systematic and Reasonable

On the one hand, rhetorical criticism is a systematic and reasonable discipline.

- Systematic: Your rhetorical criticism will more likely produce compelling insights if you systematically follow the three steps we discussed (description, interpretation, and evaluation) by answering the prompting questions we provided for each step.

- Reasonable: Critics ultimately make an argument about how an artifact functioned persuasively. As we discussed in chapter 26, an argument requires supporting claims with credible evidence. In rhetorical criticism, critics typically draw evidence from the artifact itself (i.e., quotations, descriptions, etc.), information about the artifact’s historical context (which we explore in the next chapter), and possibly from the rhetorical method used by the critic (also discussed in the next chapter). Such evidence is required to give the audience reasons to accept your claims about the rhetorical artifact.

If you do not provide sufficient, relevant evidence to support your claims—discovered through your systematic analysis of the artifact—your rhetorical criticism may be insightful but not compelling. In other words, your work will be interesting but insufficiently supported.

Creative and Manifold

On the other hand, rhetorical criticism is also a civic art, much like rhetoric itself. That means it is a creative and manifold discipline.

- Creative: No matter how carefully or comprehensively you analyze an artifact, your criticism will be influenced by your own personality, interests, choices, experiences, and values. That’s a strength of rhetorical criticism! Somewhat like painting a picture, your unique perspective can prompt creative insights and understanding about the artifact that other critics might miss.

- Manifold: Rhetorical criticism includes multiple, evolving methods, approaches, and conceptual lenses. Different critics will probably choose different approaches, notice different elements, interpret them differently, and/or offer different evaluations. That’s another strength of rhetorical criticism! The more critics who analyze a rhetorical artifact, the more insights we can gain.

Thus, if you follow the process of rhetorical criticism too rigidly or focus too much on describing the artifact rather than interpreting and evaluating it, your claims are likely to be reasonable but not insightful. They will lack the awareness and knowledge that your unique perspective can bring to your audience.

Together, the systematic/reasonable and creative/manifold qualities mean there are no “right” or “wrong” answers or conclusions when conducting rhetorical criticism. Does that mean anything goes or that any rhetorical critique you produce deserves an A grade? No! Instead, we tend to measure rhetorical criticism according to its strength.

|

Stronger Rhetorical Criticism |

|

Weaker Rhetorical Criticism |

|

Reasonable: offers compelling evidence for claims. |

Unreasonable: provides insufficient evidence for claims. |

|

|

Insightful: helps people understand the artifact and its consequences in ways they might have missed. |

Uninsightful: draws conclusions that most people already know or could readily conclude upon exposure to the artifact. |

Notice we included arrows between stronger and weaker rhetorical criticism to indicate a spectrum or range of quality possible rather than two simple categories.

Mentalities to Adopt

Because rhetorical criticism is systematic and creative, critics must adopt particular mentalities to produce insightful and compelling rhetorical criticism. These five mentalities include the following:

Because rhetorical criticism is systematic and creative, critics must adopt particular mentalities to produce insightful and compelling rhetorical criticism. These five mentalities include the following:

- Curiosity: The persistent desire to understand how rhetoric functions for audiences. This curiosity drives you to go beyond what you want or expects to see to detailed observation and analysis.

- Imagination: The ability to break apart and examine rhetorical artifacts from multiple perspectives.

- Systematic examination: The employment of a thorough and orderly approach when analyzing discourse by moving from description to interpretation to evaluation.

- Discernment: The ability to see beyond the surface of an artifact and shift from description to interpretation. You determine which rhetorical elements to focus on to generate the greatest insight into the functioning of an artifact.

- Reasoned analysis: The use of credible evidence, appropriate and representative examples, and an adherence to the standards of valid argumentation.

Summary

This chapter introduced rhetorical criticism as an intellectual discipline and form of civic engagement. It presented the understanding needed to appreciate what rhetorical criticism entails, such as the following:

- Rhetoric works as symbolic action as symbols have the power to shape thoughts, values and actions.

- Rhetorical criticism is the description, interpretation, and evaluation of rhetoric to form judgments about its functions and consequences. Description involves noticing, identifying, and explaining a rhetorical artifact’s content, form, and absence. Interpretation occurs when you make inferences about how an artifact’s content, form, and absence function persuasively. Evaluation involves making judgments about the functions and consequences of the rhetoric examined.

- Rhetorical criticism is a systematic and reasonable discipline as well as a creative and manifold field of study. Consequently, your work is judged based on its strength or weakness rather than its rightness or wrongness.

- To produce insightful and compelling rhetorical analysis, you should adopt such mentalities as curiosity, imagination, discernment, systematic study, and reasoned analysis.

Key Terms

description

evaluation

interpretation

rhetorical artifact

rhetorical critic

rhetorical criticism

symbol

symbolic action

Review Questions

- What is meant by rhetoric as symbolic action?

- What is a rhetorical artifact?

- As part of rhetorical criticism, what does description, interpretation, and evaluation refer to?

- How is rhetorical criticism systematic and reasonable? Creative and manifold? What happens when rhetorical criticism reflects one set of qualities but not the other?

- What are the intellectual qualities necessary for a rhetorical critic?

Discussion Questions

- Do you agree that our symbols compose the world we know and act within? Can you think of an example that demonstrates that? What are the implications of this claim?

- How is the process of rhetorical criticism similar to or different from scientific inquiry?

- Which set of rhetorical criticism’s qualities do you feel most comfortable with: systematic and reasonable or creative and manifold? Least comfortable? Why?

- Which of the mentalities necessary to conduct rhetorical criticism have you already developed? Which do you need to strengthen?

- Kenneth Burke, A Grammar of Motives (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 59. ↵

- Michael L. Butterworth, Baseball and Rhetorics of Purity: The National Pastime and American Identity During the War on Terror (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010). ↵

- Mark D. White, “Captain America Reminds Nation of Shared Values,” San Diego Union-Tribune, July 21, 2011, B7, https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/2011/07/21/captain-america-reminds-nation-of-shared-values/. ↵