8 Preparing to Conduct Credible Research

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Adopt a research mindset that approaches research as inquiry, values diverse perspectives, clarifies the scope and needs of research, and slows down to determine best steps.

- Distinguish differences among sources according to their timeliness, accessibility, and mutability.

- Differentiate sources from compilers and recognize artificial intelligence as a type of compiling tool.

- Assess the value of sources according to their bias, accuracy, authority, recency, and relevance.

Imagine you want to develop a speech about excessive waste. Perhaps you worry about the environmental impacts of landfills, and you feel frustrated when your friends use new plastic water bottles every day. But you don’t know enough to speak for more than a minute or two, and you don’t have any special experiences that could offer unique insights. So why should an audience listen to you or accept your opinions?

This situation calls for research, the process of learning about a topic by discovering what credible sources have said, written, or recorded about it. The best speakers use research to improve their understanding of an issue, determine or narrow their focus, and support their claims. Strong research sets apart powerfully compelling speeches from merely interesting or entertaining ones.

Good research also improves civic engagement and aids productive discourse. At a minimum, it enables you to speak accurately; you avoid basing presentations on unproven assumptions or misinformation. At most, research helps you better understand complex topics by discovering multiple perspectives. Consequently, you can help your community more fully comprehend the intricacy of the issues facing it. Finally, good research focuses your attention on ideas rather than on the people advocating them. Such a focus gives you an appropriate way to critically examine alternative positions. For all these reasons, this textbook assumes effective civic engagement requires community members like you to locate, learn from, and cite strong sources.

To help you conduct credible and effective research, this chapter will teach you how to differentiate and evaluate sources. We will begin by considering the type of mindset—or habits of mind—you should adopt to make your research more effective and enjoyable.

Research as a Mindset

To some of us, research means quickly finding internet “hits” to fill a required bibliography or finding evidence to back your position. Neither act really involves research, however. Recall we defined research as the process of learning about a topic by discovering what credible sources have said, written, or recorded about it. That means research initially requires adopting a particular mindset: one that values inquiry and diverse perspectives, clarifies the type and scope of research needed, and slows down to thoughtfully discover appropriate sources. We will briefly explain each of these habits of a research mindset.

Approach Research as Inquiry Versus Strategy

Research means educating yourself. To do that, you should approach research as inquiry: the process of studying a topic with the desire to learn. This contrasts with approaching research as strategy: the process of studying the topic only to find sources and evidence that support your preferred solution.

|

Research as Inquiry |

Research as Strategy |

|

Treats research as an opportunity to educate yourself |

Treats research as a technique to support a predetermined conclusion |

|

Open to discovering perspectives and arguments you had not considered before |

Closed off from potentially compelling reasons to reject or rethink your desired option |

|

Helps you discover or narrow your desired focus |

Blinds you to more useful or narrower foci |

|

Strengthens your understanding of the topic |

Reinforces your understanding of the topic |

|

Community-focused: Helps you locate and advocate the most suitable options for your community |

Self-focused: Helps you promote your preferred option without fully educating yourself on alternatives first |

Box 8.1 A Librarian’s Perspective on Research

Instruction librarian Lane Wilkinson distinguishes researching as strategy by referring to it simply as searching. In their words, “It’s a simple distinction: when you know the answer, or know that an answer exists, you search. When you don’t know the answer, or aren’t even sure about the question, you research.” Wilkinson goes on to distinguish research as inquiry as “involv[ing] uncertainty, persistence, iteration, and a willingness to accept that what you discover may not fit in neatly with what you believe.”[1]

When researching, then, your mindset should be to remain open to finding the best outcomes for your community, not simply searching for information that supports your predetermined conclusion.

Value Diverse Perspectives

When you approach research as inquiry, you should encounter perspectives that differ from your experience and knowledge. As we learned in chapter 7, our standpoint influences what we know and find authoritative. Recall that standpoint theory suggests that our social identities influence our knowledge of the world and our perceptions of what is true or normal. Thus, we’re likely to dismiss or discount perspectives that emerge from differing standpoints as foreign or even untrue.

When you approach research as inquiry, you should encounter perspectives that differ from your experience and knowledge. As we learned in chapter 7, our standpoint influences what we know and find authoritative. Recall that standpoint theory suggests that our social identities influence our knowledge of the world and our perceptions of what is true or normal. Thus, we’re likely to dismiss or discount perspectives that emerge from differing standpoints as foreign or even untrue.

A research mindset encourages us, instead, to be self-reflexive of our standpoint and to value experiences and knowledge that differ from our own and from each other. Indeed, among research’s benefits is learning how diverse people, groups, and organizations define, experience, and talk about the issue and possible ways to address it.

Clarify Research Scope and Needs

Another habit of a research mindset is to clarify your research needs and scope. First, how broadly or narrowly should you focus your research? Think of yourself somewhat like Goldilocks, who, in the fairy tale, entered the Three Bears’ house and tested their chairs, beds, and bowls of porridge to find the ones that were not too hard/hot or too soft/cold but were “just right” for her needs. Similarly, your goal is to determine the scope of your research that is “just right” for your needs: not too broad or too narrow. Review your assignment instructions or talk with your instructor for guidance.

Box 8.2 Researching Too Broadly or Too Narrowly

Imagine your speech topic regards mental health, and you need to conduct research to learn more.

Researching too broadly: Researching “mental health” will result in an overwhelming number of sources that may not directly relate to each other.

Researching too narrowly: Alternatively, beware of overly narrowing your focus, which may result in few or no useful sources. An example of an overly narrowed topic is “depression in eighth grade boys who live in Iowa.”

“Just right”: What research topics qualify as “just right” in breadth will vary based on your audience and speaking situation. For a classroom speech, though, you might consider researching about particular types of mental health challenges (e.g., depression, PTSD, gender dysphoria), specific kinds of people affected (e.g., men, elderly, people of color), or particular regions impacted (your state, rural towns, college campuses).

Second, what type of evidence and sources do you need? Too often, we make assumptions about what sources compose “research”: scientific data, legal rulings, news articles? Instead of making assumptions, clarify exactly what types of information you need. Consider your speaking goal and the type of speech you are delivering (deliberative, persuasive, etc.) as well as your audience. As we will discover in chapter 11, effective speakers adapt their speeches to their audiences. That includes considering the kinds of sources and information your audience deems credible and compelling. In some cases, it may be preferable and more helpful, for instance, to cite a press release that describes the conclusions of a scientific experiment rather than citing the scholarly article itself.

Slow Down

It is tempting to immediately jump online and search Google or ChatGPT for your topic. The quickness of the results feels satisfying. But are the results likely to meet your needs?

After considering your research needs and scope, take a moment to thoughtfully identify the best way to locate the types of information you need. If you decide you need a press release, then look for news articles by using a database such as Nexis Uni or searching specifically on Google News. If, instead, you need a scientific article, then search a database like PubMed that features such scholarship or use Google Scholar.

After considering your research needs and scope, take a moment to thoughtfully identify the best way to locate the types of information you need. If you decide you need a press release, then look for news articles by using a database such as Nexis Uni or searching specifically on Google News. If, instead, you need a scientific article, then search a database like PubMed that features such scholarship or use Google Scholar.

Slowing down also means not necessarily accepting the first relevant source you find. We will talk about evaluating sources in “Criteria to Consider When Finding Sources: BAARR.” For now, we recommend you read laterally, meaning that you find and review several sources about the same topic. Such exposure will help you decide if you have narrowed your topic appropriately, if you are finding the types of evidence and information you need, and if the information you are finding is widely shared or is subject to debate or disagreement.

Box 8.3 Adopting a Research Mindset

If you want to conduct research about reducing waste, adopting a research mindset could mean that you do the following:

Research as inquiry: Don’t assume your college community doesn’t care enough about the environment or waste management, and don’t assume recycling is the best answer. Instead, explore exactly what can get recycled in your area and how the global economy might impact that. Discover how waste reduction might impact the problem and if and why your community isn’t already reducing its waste.

Value diverse perspectives: Consider not only what other students experience and think or even just what administrators say. Find and learn from custodial workers at your college, any clubs or organizations devoted to environmental concerns, waste management in your city or town, and studies about which items actually get recycled.

Clarify research scope and needs: For the scope, do you want to address waste only on your college campus or also in your city or town? Do the two affect one another? Should you consider how state regulations might impact how waste is handled? Might you expand your research to other countries for alternative models of waste management, reduction, or recycling?

As for your research needs, do you require state or national data about how much waste is currently produced? Might offices or people at your university help you attain more local information and perspectives? Would examples or models from other colleges or states prove more useful? Might a survey or public opinion poll help you understand consumer behaviors?

Slow down: Where should you look first? Might local newspaper archives be helpful, or perhaps conducting interviews may be most effective? Will you find the type of research you need, instead, in national news articles or scholarly studies? Perhaps you can look at collegiate press releases or even reviews of campus dining companies to learn about innovative ways to reduce, reuse, or recycle waste.

Differences Across Sources

With so many sources available online, it can be difficult to differentiate one from another. To the untrained eye, sources can all look similar: words on your screen, possibly with images or even videos. Such similarity can prevent you from recognizing important differences across sources that can help you decide which sources best suit your research needs. In this section, we highlight how sources use different processes in creating and publishing information and how sources differ from compilers.

Differences in the Information Creation and Publication Process

If you were shown digital copies of a newspaper article, a book chapter, and a blog, could you quickly tell they are very different types of sources? Do you know why? Clues can be found in their timeliness, accessibility, and mutability.

Timeliness

Timeliness concerns how fast or slow the process was to finalize and publish the source.

Timeliness concerns how fast or slow the process was to finalize and publish the source.

If we think of timeliness on a spectrum, then some sources will fall toward the faster end. An amateur blog or a social media post can be published online immediately, because typically one person creates and publishes a post. Professional news or trade journal articles also strive for a sense of immediacy (since journalists want to report what is “new”), but they typically take a little more time, since story ideas need to be approved, edited, and formatted, often by additional people. The same is true for many social media influencers, such as YouTubers who employ teams of people to imagine new ideas, plan and record them, and then edit and post the resulting video.

Shifting toward the even slower end of the spectrum, we find scholarship. Scholarly books and articles are produced by professional academics or researchers. While the pace can vary, most scholarship takes considerable time to publish. The lengthy process includes time to prepare, write, and submit a manuscript to a journal or university press; undergo review by other people in the same scholarly field; revise based on their feedback; possibly go through a second round of review and revision; and finally be formatted for publication. The process can take anywhere from several months to a year to complete before being published.

Shifting toward the even slower end of the spectrum, we find scholarship. Scholarly books and articles are produced by professional academics or researchers. While the pace can vary, most scholarship takes considerable time to publish. The lengthy process includes time to prepare, write, and submit a manuscript to a journal or university press; undergo review by other people in the same scholarly field; revise based on their feedback; possibly go through a second round of review and revision; and finally be formatted for publication. The process can take anywhere from several months to a year to complete before being published.

|

FASTER |

|

SLOWER |

|

Social media post |

Professional news article |

Scholarly book |

Accessibility

Timeliness corresponds with a source’s accessibility. In this context, accessibility refers to whether and how easily the author can directly publish their work. As mentioned, faster sources tend to give the author more direct access to publishing. If you had the funding, for instance, you could create a website today and publish nearly whatever you want. Slower sources tend to have more gatekeeping, which is when people or groups other than the author have the power to decide what gets published and how. As we explained, professional journalists and scholars need to obtain several other people’s approval before their work can be seen by a wider audience.

Box 8.4 Research Trade-Offs Related to Timeliness and Accessibility

A source’s timeliness and accessibility do not determine its worth, but they do convey research trade-offs you should consider:

| Faster, More Directly Accessible Sources (e.g., Social Media Posts) | Slower, More Heavily Gatekept Sources (e.g., Scholarly Books) | |

| + | Can provide immediate information and opinions about very current events, even as they unfold in real time | Are more likely to include valid information |

| – | Typically lack depth and may include inaccurate information | Cannot directly address very recent happenings |

Mutability

Finally, sources vary in their mutability, or likelihood of changing. They may all appear immutable (stable), but what you read on your screen today may not be the same when you access that source in a month or year.

It depends on the type of source. Some sources, such as online news articles and organizations’ websites, are likely to change over time. Even websites maintained by authoritative sources like the United States government tend to alter as their information is updated. The URL remains the same, but the information or even titles will change. As another example, social media posts can alter, since the original author can edit or even delete the post. In contrast, other sources are reliably static; that is, they don’t change over time. Once a scholarly article or book is published, that’s it. It will be the same every time you return to it.

The likelihood of a source changing impacts not only how you cite it (which we discuss in chapter 9) but also how difficult or easy it is to find again. If you use a source that is likely to change or even disappear, we recommend you “freeze” it by saving a copy or a screenshot with the date you saved it. If you want to return to a particular digital source, you might also save it by creating a Perma Link through Perma.cc if your college library has a subscription you can use. Alternatively, you can save the source to Internet Archive’s WayBack Machine at https://archive.org/web/. That service can also come in handy if you failed to save a source and are desperate to find it again!

Box 8.5 Differences Across Sources

Online sources may appear similar, but they differ in important ways based on the following:

- Timeliness: how slowly or quickly they are created and published.

- Accessibility: how directly or indirectly an author can publish their work.

- Mutability: whether the content is dynamic or static over time.

Sources Versus Compilers

Though we have used the term, we have not yet defined what we mean by a source. That term matters, because you need to differentiate between a source and a compiler. For our interests, a source is an original communication product that has been written by one or more human authors and published for an audience. A book, a news article, and a speech are all sources. A compiler is a service that gathers information from multiple sources and makes it available. Two types of compilers that students often confuse with sources are research databases and artificial intelligence (AI).

Research Databases

A research database is an organized online storehouse of information that can easily be searched to retrieve desired sources. Numerous research databases exist with collections ranging from scholarly articles and ebooks to news media broadcast transcripts and legal documents.

Most of the popular research databases are actually databases of databases. That is, they include multiple collections of sources. Popular examples include JSTOR, ProQuest, and Academic Search Complete. College libraries typically subscribe to several databases, allowing students to access them for free as long as they enter through the library’s website. Check your college library’s home page or talk with a reference librarian at your university about available databases and how to access them. Often, if you go through your college’s library home page, you can access for free the research databases the library subscribes to. If, instead, you go directly to a database’s website, you will likely run into a paywall.

A research database is a compiler, not a source, because it is a service that pulls together and presents existing sources based on your search terms. Consequently, it can make researching for some sources easier and quicker. However, it is not a source.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Many types of AI exist, but at its core, AI draws on, retrieves, and compiles scores of sources to produce content. The content is prompted by a user’s questions (while using an AI chatbot) or search terms (while using a search engine like Google). The output—such as the paragraphs an AI chatbot writes in response to your request or the images an AI text-to-image generator might produce—can make AI appear like a source. However, AI is not a source as we have defined it. It is not human, and it does not (yet) produce original communication as we—your authors—think of originality.

Instead, machine-learning AI uses algorithms that very quickly analyze existing data from myriad sources to find patterns—which is the compiling function—and then predict a useful or appropriate response. AI may assemble the predicted content in novel or unique ways, but it is based on the sources and data that AI draws on.

PCMag’s K. Thor Jensen explained the shortcomings of generative AI: “Computers aren’t capable of what we would consider original thought—they just recombine existing data in a variety of ways. That output might be novel and interesting, but it isn’t unique.”[2]

AI’s function as a robust compiler rather than a source helps explain why it tends to unreflectively repeat the dominant racist, sexist, and homophobic biases and stereotypes commonly found in existing sources[3]—and why you are more likely to encounter factual errors when using generative AI. According to PCMag’s K. Thor Jensen, the datasets AI trains on become outdated and reflect societal biases.[4]

Jensen also points to two additional factors for AI’s errors: the complexity of AI’s coding, which prevents our ability to trace the source of an inaccurate response to correct it, and AI’s requirement to produce a response to your query even if it does not have the answer.[5]

“A generative AI model cannot tell you whether something is factual; it can pull data only from what it’s been fed. So if that data says that the sky is green, the AI will give you back stories that take place under a lime-colored sky. When ChatGPT prepares output for you, it doesn’t fact-check or second-guess itself. And while you can correct it during your session, those corrections aren’t fed back to the algorithm. This software is comfortable lying and making things up because it has no way not to, and that makes relying on it for research especially risky.”[6]

Further, people can use AI to deliberately produce false videos or recordings of famous people, for instance, doing or saying things that never occurred. While many of these fakes are produced in good fun (like hearing Adele’s version of a Beatles’ song), the technology can easily be used more maliciously to trick audiences into believing falsehoods.

Therefore, we warn you to not rely on AI for your research. Not only is it a compiler rather than a source, but it also risks being inaccurate or used purposefully to deceive—a point we made in chapter 5 and explore more fully in chapter 9.

Having said that, AI can help you get started on a speech by functioning as a feedback tool. As we suggested in chapter 5, you might use AI to brainstorm arguments and counterpoints. It can also help you restate complex ideas more clearly and produce effective visual aids. If you want to use AI in any of these ways,

- consult your instructor and/or librarian to discuss if and how you can use AI,

- consider the ethical implications involved in doing so (chapter 5),

- explicitly acknowledge your use of AI by citing which tool you used and how (chapter 9),

- double-check any sources AI cites to ensure they actually exist and provide useful information, and

- find additional sources and develop and synthesize the ideas you gain on your own.

Criteria to Consider When Finding Sources: BAARR

In addition to adopting a research mindset and distinguishing differences among sources, we urge you to recognize that not all sources are equally credible. Some sources may be easy to find but are outdated and provide inaccurate information, for instance. If you adopt such sources, you set a very low bar for references and evidence, which will reflect poorly on your credibility and weaken your advocacy.

Instead, we invite you to keep in mind five criteria when you find sources. You will notice they form the acronym BAARR to remind you to set the bar high when finding sources. They include the following:

Bias

Accuracy

Authority

Recency

Relevance to your topic

Avoid thinking of these as a checklist; rather, use the criteria to answer questions about each source so you can make thoughtful decisions.

Bias

Bias is a predetermined commitment to a particular ideological or political perspective. A biased source is one that openly professes such a commitment or is commonly recognized as doing so. Biased sources can include those that see the world through a predetermined set of presumptions, beliefs, and/or philosophies.

Bias is a predetermined commitment to a particular ideological or political perspective. A biased source is one that openly professes such a commitment or is commonly recognized as doing so. Biased sources can include those that see the world through a predetermined set of presumptions, beliefs, and/or philosophies.

Box 8.6 Biased Sources

Biased sources include the following:

- politically aligned sources (e.g., the liberal magazine Mother Jones and the conservative magazine National Review)

- some nonpartisan organizations (e.g., People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals [PETA] and the Food Research and Action Center)

Biased sources are likely to produce information and perspectives that reflect or even reinforce their preferences. To return to a speech on excessive waste again, if you interviewed the board chair of Keep America Beautiful, they would certainly provide information on why recycling is important and should be improved.

The point of this is not that you should never make use of biased sources. Indeed, most sources include some kind of bias. Fortunately, many biased sources can be considered authoritative, relevant, and recent. Rather, you should utilize biased sources knowingly and incorporate them into a broad range of sources, including those that are not inherently biased or are more balanced. When you use a biased source in your presentation, acknowledge it as such. This shows the audience you are an honest speaker because you make your sources fully known rather than deceptively use biased sources to manipulate your listeners.

Two of the most helpful ways to identify whether and how much a news source is politically biased are through Ad Fontes’ online Media Bias Chart and the AllSides Media Bias Chart.[7] Both reveal that biased sources vary in their degree of bias. The Ad Fontes’ chart also accounts for sources’ degrees of reliability or accuracy. We turn to this important consideration next.

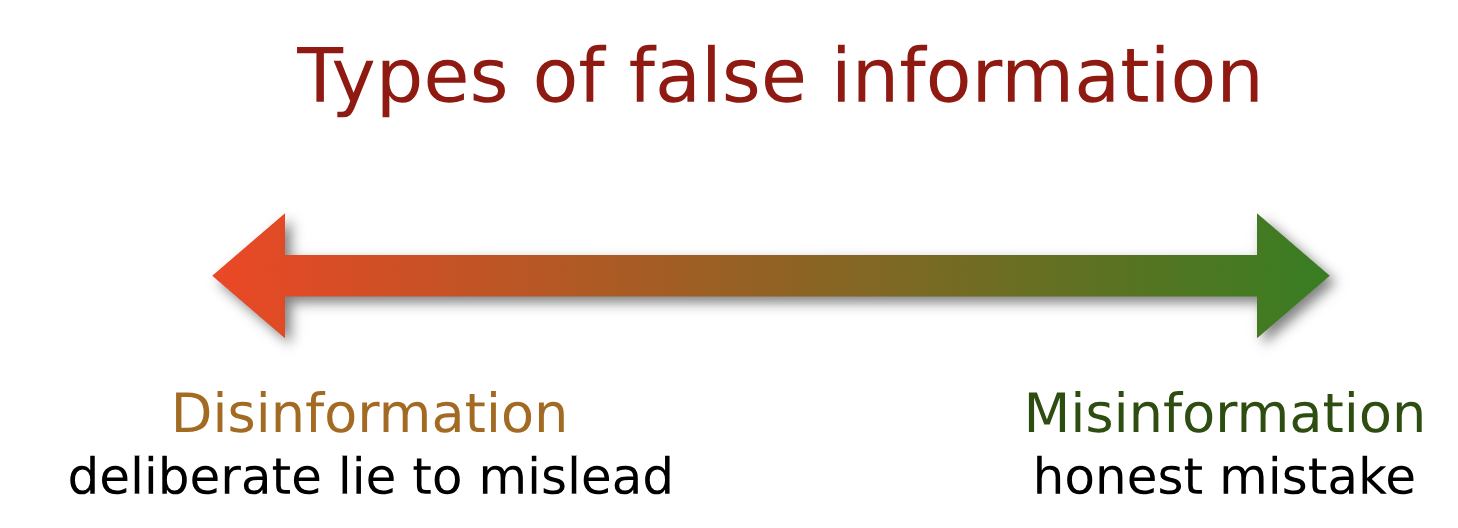

Accuracy

Whatever your immediate speaking goal, your ultimate achievement is to aid your community in thinking through issues and making sound decisions. Fulfilling that objective requires accurate information. Accuracy refers to the truthfulness or veracity of the information provided by a source. Unfortunately, misinformation and disinformation abound. As defined in chapter 2, misinformation is the unintentional spread of inaccurate or false claims that lack sufficient or valid evidence and/or identifiable and credible sources (i.e., an innocent mistake or gaffe). Disinformation, in contrast, refers to a deliberate attempt to spread wrong information to mislead listeners.

Whatever your immediate speaking goal, your ultimate achievement is to aid your community in thinking through issues and making sound decisions. Fulfilling that objective requires accurate information. Accuracy refers to the truthfulness or veracity of the information provided by a source. Unfortunately, misinformation and disinformation abound. As defined in chapter 2, misinformation is the unintentional spread of inaccurate or false claims that lack sufficient or valid evidence and/or identifiable and credible sources (i.e., an innocent mistake or gaffe). Disinformation, in contrast, refers to a deliberate attempt to spread wrong information to mislead listeners.

Box 8.7 Examples of Disinformation

Disinformation can be spread by a range of people, groups, and organizations—including some that may surprise you or do not appear to deliberately supply disinformation. The following are examples:

- Some government actors distribute disinformation for propagandistic purposes. We can find examples historically in the lies US high-ranking government officials knowingly made about the Vietnam War (famously revealed in the Pentagon Papers) or in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s falsehoods to his own people about its war on Ukraine.

- Interest groups have been created online to promote disinformation and political polarization around topics such as climate change. They can have convincing-sounding names like the Climate Intelligence Foundation, and their online presence can appear authoritative, but their bias against environmentalism corresponds (in this case) with strategically promoting disinformation.

Obviously, you must be wary of both misinformation and disinformation so you do not mislead your listeners. Saying that can be easier said than done, since sources that meet other criteria—that is, they are authoritative, recent, and relevant—can present disinformation.

Your best bet, then, is to read laterally and do some background reading. As we established earlier, reading laterally means finding and reviewing several sources about the same topic, and background reading involves going to reference sources that reflect information and facts that are consensually agreed to by a wide variety of parties. These strategies will help you decide if the information you are finding is widely shared or is subject to debate or disagreement. If a source you have found directly contradicts what you are finding elsewhere (for instance, that climate change is occurring), that can be a clue that the source may be promoting misinformation or disinformation and should be further investigated.

Authority

Authority relates to the expertise, power, or recognized knowledge a source has concerning a topic. We might distinguish among various types of authority a source may exercise: subject, societal, and special experiences.

Authority relates to the expertise, power, or recognized knowledge a source has concerning a topic. We might distinguish among various types of authority a source may exercise: subject, societal, and special experiences.

Subject Authority

Subject authorities are sources with trained expertise on the topic. A scholar with a PhD in waste management studies would be a subject authority on that topic. Somewhat similarly, the Environmental Protection Agency would also be an authoritative source about environmental effects of landfills, because the agency’s entire work—that is, their subject expertise—focuses solely on environmental concerns. Sources that have also been reviewed by subject experts—such as scholarly publications—carry even more authoritative weight.

Societal Authority

Societal authority emphasizes a source’s power to control outcomes based on their position within a society or organization. Your mayor would be considered an authoritative source, for instance, about your city’s waste management challenges. Similarly, Harvard University’s Office for Sustainability wields societal authority over that university’s reduction, recycling, and disposal of waste.

Authority from Special Experiences

Authority can also be accrued through special experiences. For instance, a person who grew up in a neighborhood near a hazardous waste site could speak with some authority on that experience. Perhaps they attended town meetings about the site, experienced ill health effects, or could share the site’s effects on their quality of life.

Recall that sometimes special experiences  are due to one’s positionalities. In chapter 7, we discussed how, according to standpoint theory, a person with a marginally situated positionality is likely to know more about a relevant system of power because they are more likely to encounter and navigate it. Hazardous waste sites are more often located near neighborhoods of low-income families and people of color.[8] The special experiences of such a person who grew up near a hazardous waste site might also be able to shed light on how such issues as racism and classism contribute to inequity.

are due to one’s positionalities. In chapter 7, we discussed how, according to standpoint theory, a person with a marginally situated positionality is likely to know more about a relevant system of power because they are more likely to encounter and navigate it. Hazardous waste sites are more often located near neighborhoods of low-income families and people of color.[8] The special experiences of such a person who grew up near a hazardous waste site might also be able to shed light on how such issues as racism and classism contribute to inequity.

It is important for you to assess the type and degree of a source’s authority—both for yourself and on behalf of your audience as part of your obligation to ethical speech preparation, discussed in chapter 5. Such assessment helps you determine how much you and your audience can trust a source to understand the topic. It also prevents you from dismissing sources that can offer useful information but may not be authorities on the subject. Reference librarians are great resources and can answer questions you may have about finding authoritative material. Don’t be afraid to approach one of them at your university or college library to ask for help.

Recency

The recency of your sources is also important. Recency refers to how up to date the information is that a source provides. If the source and its information are outdated, then it is not terribly useful to you or your audience. Imagine if you began a speech about waste by sharing data from ten years earlier. “What about now?” your audience would immediately wonder.

Instead, when  addressing community concerns and issues, seek sources published recently. Even persistent community issues can change at any moment. If your town’s mayor announces a new waste reduction plan the week before your speech, you would need to incorporate that announcement and revise your speech accordingly. Otherwise, your audience will likely dismiss your speech as obsolete.

addressing community concerns and issues, seek sources published recently. Even persistent community issues can change at any moment. If your town’s mayor announces a new waste reduction plan the week before your speech, you would need to incorporate that announcement and revise your speech accordingly. Otherwise, your audience will likely dismiss your speech as obsolete.

Of course, not every topic requires the use of recent sources, however. For example, historical facts seldom change and thus can be supported by older sources. Landmark works that have received acclaim might maintain a timeless character. On the other hand, our understanding of history can alter with new archival research, the release of private papers, and new interpretations of historical documents. Thus, a more recent treatment of a traditional topic may, depending on its credibility, prove to be a superior source.

Relevance

Not every source that mentions your topic is as relevant as another. Relevance refers to the degree of association between the source, a speaker’s topic, and their audience. Highly relevant sources offer information that directly addresses your particular focus on your topic and resonates with your specific audience. No matter how interesting the information or ideas presented by a source, it won’t help your speech if it doesn’t relate directly to your topic or your audience.

Not every source that mentions your topic is as relevant as another. Relevance refers to the degree of association between the source, a speaker’s topic, and their audience. Highly relevant sources offer information that directly addresses your particular focus on your topic and resonates with your specific audience. No matter how interesting the information or ideas presented by a source, it won’t help your speech if it doesn’t relate directly to your topic or your audience.

Box 8.8 Relevant Sources for a Speech About Excessive Waste

If you wanted to motivate your college community to reduce waste, you would desire sources relevant to your audience and particular angle.

- You might find articles in your college newspaper to be more compelling, for instance, than national news articles.

- You might turn to a source such as The College Sustainability Report Card, an annual survey conducted by the Sustainable Endowments Institute that grades each college and university’s efforts at sustainable living. What if you discovered that your college’s chief rival consistently scored a much higher grade than your own campus? That might get your audience’s attention and perhaps bring out its competitive spirit!

The point is that with each speech, you must consider which sources work for your particular topic and audience.

Together, the criteria discussed—bias, accuracy, authority, recency, and relevance—can help you decide which sources to use to develop your speech and which to dismiss. Opt for sources that best meet your needs, using the criteria as guidelines. When in doubt, you can also always ask a reference librarian for help.

Box 8.9 Criteria to Evaluate Sources: Setting a High BAARR

When determining the value and veracity of a source, consider the following criteria. Think of each as a spectrum rather than a box to be checked.

Bias: A predetermined commitment to a particular ideological or political perspective.

- Who are the publishers, sponsors, and/or authors of the source? Who paid for the source’s creation? What can you learn about them?

- How is the source described, such as in an “About” section or mission statement?

- How do other sources describe this source, and where does it fall in the Ad Fontes Media Bias chart or on the AllSides Media Bias chart?

- What evidence of bias, if any, is present in the material itself?

Accuracy: The truthfulness or veracity of the information provided by a source.

- Has the material been reviewed or vetted by an editor or reviewers?

- Does the material line up with information and facts provided by other sources about the same topic? Do a wide variety of parties agree on the same facts?

- Can you find reviews or responses to the material?

Authority: The expertise, power, or recognized knowledge a source has concerning a topic.

- Who is the author, and what type of (relevant) authority do they have, if any?

- Are they an expert on the subject matter? Do they have a title or degree that demonstrates their expertise?

- Does their position in society or an organization lend them authority on the subject?

- Have they had relevant special experiences that authorize the information they provide?

Recency: How up to date the information is that a source provides.

- What is the publication date or the date the material was last updated?

- Have more recent sources appeared that alter or revise the information the source provides?

- Are you using the source to establish a historical fact or to offer a more recent interpretation of a historical occurrence?

Relevance: The degree of association between the source, a speaker’s topic, and their audience.

- Does the source directly address your particular focus on the topic?

- How well will this source resonate with your specific audience?

Summary

This chapter has introduced you to the mindset, considerations, and evaluative criteria needed to prepare to conduct credible research. Good research produces more effective speeches and aids productive discourse.

- We recommend you adopt a research mindset that approaches research as inquiry, values diverse perspectives, clarifies the scope and needs of research, and slows down to determine best steps. If you approach research in this way, you will more likely enjoy the purpose of research: to learn about a topic by discovering what credible sources have said, written, or recorded about it.

- Distinguishing differences among sources can help you decide which sources best suit your research needs. In particular, it is important to appreciate the different processes sources use in creating and publishing information as well as how sources differ from compilers.

- Artificial intelligence is a robust compiler rather than a source. While it may help stimulate speech ideas, it does not qualify as a source and therefore should not be used as such or to find sources.

- Assess the value of sources by asking questions about their potential bias, accuracy, authority on your topic, recency, and relevance to your topic. Use these criteria to set a high BAARR for your research.

Key Terms

accessibility

accuracy

authority

bias

compiler

database

mutability

read laterally

recency

relevance

research

research as inquiry

research as strategy

source

timeliness

Review Questions

- What role does research play in civic engagement? How does research aid communal decision-making?

- What is the difference between researching as a mode of inquiry and researching as a strategy?

- What are major differences in the process sources use to create and publish information? What’s the difference between a source and a compiler?

- What criteria should you consider when finding sources? What does BAARR refer to?

Discussion Questions

- Is it ever appropriate to approach research as a strategy or to focus on a single perspective? When? Why?

- How might AI aid or harm your research? How have you used it for a class assignment, or how have you heard of other people using it for research?

- What are the best ways you have found to recognize and avoid misinformation and disinformation? Have you ever accidentally failed to recognize either? Why?

- Are there any circumstances when it is ethical to use sources biased in only one direction? When? Why?

- Lane Wilkinson, “Is Research Inquiry?,” Sense and Reference: A Philosophical Library Blog, July 15, 2014, https://senseandreference.wordpress.com/2014/07/15/is-research-inquiry/, archived at https://perma.cc/9YMJ-5RMA. ↵

- K. Thor Jensen, “Yes, Machines Make Mistakes: The Ten Biggest Flaws in Generative AI,” PCMag, April 18, 2023, https://www.pcmag.com/news/yes-machines-make-mistakes-the-10-biggest-flaws-in-generative-ai. ↵

- A. W. Olheiser, “AI Automated Discrimination. Here’s How to Spot It,” The Highlight by Vox and Capital B, June 14, 2023, https://www.vox.com/technology/23738987/racism-ai-automated-bias-discrimination-algorithm; Nitasha Tiku, Kevin Shaul, and Szu Yu Chen, “These Fake Images Reveal How AI Amplifies Our Worst Stereotypes,” Washington Post, November 1, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2023/ai-generated-images-bias-racism-sexism-stereotypes/. ↵

- Jensen, “Yes, Machines Make Mistakes.” ↵

- Jensen, “Yes, Machines Make Mistakes.” ↵

- Jensen, “Yes, Machines Make Mistakes.” ↵

- “Media Bias Chart 12.0,” Ad Fontes Media, January 2024, https://www.adfontesmedia.com/static-mbc/; “AllSides Media Bias Chart, Version 10.1", AllSides, 2025, https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/media-bias-chart. ↵

- “Targeting Minority, Low-Income Neighborhoods for Hazardous Waste Sites,” University of Michigan News, January 19, 2016, https://news.umich.edu/targeting-minority-low-income-neighborhoods-for-hazardous-waste-sites/. ↵