13 Organizing Your Main Points

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Organize the main points of a speech.

- Distinguish linear from nonlinear patterns of arrangement.

- Identify several patterns of arrangement for organizing main points.

The previous chapter stressed the importance of speech organization. It also helped you develop a strong thesis statement. As a speaker, what’s your next step?

It’s time to develop and organize the body of your speech, guided by your thesis statement. The speech body is typically the largest or longest part of a presentation. It includes everything except the introduction and conclusion, which we explore in the next chapter. Here we focus solely on your main points, or the major ideas or claims that compose a speech’s body and support the thesis statement. First, we will briefly provide pointers for initially finding possible main points. Next, we will more thoroughly discuss several patterns of arrangement. Throughout our guidance, we will reference your audience. In this chapter, the audience refers to your direct audience, who we defined in chapter 10 as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech.

Finding Possible Main Points

Look through your research and identify the information and evidence most pertinent to your thesis statement. Begin grouping that information into one-sentence ideas or claims as best as you can. Then evaluate what you have. How do they fit together—or what does not fit with the others? What relationships can you identify among these points? Answering these questions can help you discover your main points. Then you can turn to a pattern of arrangement to order the material in your speech.

Alternatively, you might begin with a pattern of arrangement. Use it to help you sift through your research for the most relevant or useful elements. The pattern can provide guidance and order the material simultaneously. Either way, you’ll find a pattern of arrangement very useful for finding and organizing your main points.

In the next section, we share two types of patterns of arrangement. We recommend you approach these as tools for identifying and constructing the type of speech you want to deliver.

Patterns of Arrangement

A pattern of arrangement is a specific guide, or template, for choosing and organizing the main points of a speech. The arrangement helps determine both the content of the main points and their order. As you consider how to arrange your speech body, spend some time thinking about the type of thesis you are making, the types of supporting materials you are presenting, and the type of response you are asking of your audience. Knowing what you want your audience to get out of the speech (or what an assignment asks you to demonstrate) will help you consider how best to arrange your material.

Interestingly, each of these patterns is not only reflective of a clear speech structure but also representative of the most common ways we tend to think about or make sense of our world. We have divided the patterns into those that follow a linear logic and those that adopt a nonlinear approach.

By linear, we mean a progression of main points that moves in a “straight line”—with one step logically leading to the next—all clearly in support of a thesis that is stated early in the speech. Consequently, linear patterns tend to value explicit statements of claims and evidence as support for the thesis. By prioritizing such explicit connections, however, linear patterns can seem unartful or dull, especially when poorly developed or for audiences more accustomed to nonlinear patterns.

By linear, we mean a progression of main points that moves in a “straight line”—with one step logically leading to the next—all clearly in support of a thesis that is stated early in the speech. Consequently, linear patterns tend to value explicit statements of claims and evidence as support for the thesis. By prioritizing such explicit connections, however, linear patterns can seem unartful or dull, especially when poorly developed or for audiences more accustomed to nonlinear patterns.

In contrast, nonlinear refers to an approach that adopts a more circuitous or indirect route to, or in support of, a thesis. These approaches may circle around the thesis through repetitive, but varied, main points, or their connection between the main points and the thesis may not be immediately obvious. Because nonlinear patterns tend to value vividness, they are more likely to incorporate stories, examples, and testimony to bring the central focus to life. The detailed content of these supporting materials may be as important as the “point” to be drawn from them. These patterns may build up to a thesis as the final “a-ha” or culminating moment that pulls all the support together, though they can also be thesis driven. As a result, nonlinear patterns can be very engaging and moving but can also be difficult to follow for audiences more accustomed to linear patterns.

In contrast, nonlinear refers to an approach that adopts a more circuitous or indirect route to, or in support of, a thesis. These approaches may circle around the thesis through repetitive, but varied, main points, or their connection between the main points and the thesis may not be immediately obvious. Because nonlinear patterns tend to value vividness, they are more likely to incorporate stories, examples, and testimony to bring the central focus to life. The detailed content of these supporting materials may be as important as the “point” to be drawn from them. These patterns may build up to a thesis as the final “a-ha” or culminating moment that pulls all the support together, though they can also be thesis driven. As a result, nonlinear patterns can be very engaging and moving but can also be difficult to follow for audiences more accustomed to linear patterns.

While you might be tempted to see patterns of arrangement as simple organizational devices, recognize that by using them, you are tapping into human logic and sensemaking at a deeper level. Keep in mind that there is not a single, correct pattern of arrangement. You may decide on a different organizational structure depending on subject, specific purpose, thesis, or audience.

Linear Patterns of Arrangement

Categorical Arrangement

A categorical approach uses a “category” of elements—such as parts, forms, functions, methods, characteristics, perspectives, or qualities of a topic—as its organizing principle. All the main points belong to that category. For example, a speaker who wants to convince their classmates to volunteer time toward youth development could identify three types of local programs they might join: after-school tutoring centers, mentoring programs, and sports teams.

A word of caution about categorical arrangement: Novice speakers too quickly resort to this pattern of organization without considering other options more carefully. We suggest you use it as a last resort for two reasons. First, if not approached with some creativity and imagination, this pattern is less likely to capture and sustain your audience’s interest in your topic. Second, this pattern runs the highest risk of seeming random or disorganized if you do not include transition words (discussed in chapter 14) that clearly define the category that connects your main points.

Chronological Arrangement

A chronological structure uses time as its organizing principle. Thus, a chronological speech often takes a past-present-future approach, organizes its main points by historical era, or addresses issues as they unfolded through time. If you are giving a speech requesting more funding for your community charity, you might persuade your audience to donate based on a chronological pattern that shows the positive impact your agency has had over time. You might end by stressing what the agency could do in coming months and years with more support.

Spatial Arrangement

A spatial structure is sequential, moving through a progression of elements. The pattern essentially demonstrates how we get from point A to point B or what is similar and different as we move from point A to point B. Often overlooked by speakers, this pattern can be a powerful tool if you want to show, for example, how different regions of the country are affected by a particular policy or how different sites in a city appeared before and after a historical event.

Cause-Effect Arrangement

In the cause-effect arrangement, a speaker offers two main points:

- “Cause”: Describes a source, reason, or existing condition

- “Effect”: Identifies or predicts the effects of the cause named in the previous point

For instance, if you want to increase people’s concern about air pollution, you might first establish current pollution levels and then explain their effects on physical health.

Cause-effect arrangement is a particularly useful approach in showing the relationship between ideas or actions. For example, you might use this pattern if you wish to show how a local organization has been positively affected by a grant you seek to renew.

A word of caution about this pattern: When talking about cause and effect, a speaker needs to avoid oversimplifying a situation. Before you use this pattern, ask yourself whether there are multiple causes that should be considered to do justice to the problem. Will your credibility and strength of reasoning be undermined if you address only one of those causes?

Problem-Solution Arrangement

The problem-solution pattern is frequently used in persuasive speeches and proceeds by first documenting the nature, extent, and source of the problem before advocating a solution. Like the cause-effect arrangement, this type of speech typically has two main points that are succinctly divided between aspects of the “problem” and the “solution” advocated by the speaker. Examples might include explaining a particular solution to the deteriorating middle school in your community or a plan for improving air quality in your city.

Problem-Alternatives-Solution Arrangement

An attractive alternative is the problem-alternatives-solution arrangement. This pattern includes a middle main point that names and counters one or more alternative solutions before advocating for the solution the speaker sees as most promising. This approach allows the speaker to address popular counterarguments and policies in the alternatives section of the speech.

Box 13.1 Sample Problem-Alternatives-Solution Arrangement

Recall Riley’s speech on animal abuse and welfare in the previous chapter. They ultimately chose the problem-alternatives-solution arrangement for their speech. The main points of their presentation include the following:

- Problem: Riley established the existence of animal neglect and cruelty in their county and state.

- Alternatives: Riley described a recent initiative to stiffen penalties for pet abuse and argued why that initiative was an ineffective solution.

- Solution: Riley advocated for their preferred approach of educating the public about animal abuse and how to report it, and they provided ways for the audience to spread the word.

Problem-Cause-Solution-Solvency Arrangement

A second alternative is the problem-cause-solution-solvency pattern. This pattern typically includes four main points:

- Problem: Identify the nature and extent of the problem.

- Cause: Address the source of the problem.

- Solution: Name the solution and emphasize how it directly targets the cause of the problem.

- Solvency: Discuss the practicality, or costs and benefits, of implementing the solution.

Box 13.2 Sample Problem-Cause-Solution-Solvency Arrangement

The previous chapter considered a speech that advocated for an on-campus food pantry. If the speaker adopted a problem-cause-solution-solvency pattern of arrangement, they could organize their main points this way:

- Problem: Establish the prominence of anxiety and depression among college students.

- Cause: Identify food insecurity as a contributing factor to students’ anxiety and depression.

- Solution: Offer the solution of an on-campus food pantry.

- Solvency: Suggest where exactly the pantry could be located, identify where funding might come from, and cite the many other successful university food banks around the country.

Refutative Arrangement

The refutative arrangement, sometimes called the negative method of arrangement, is best suited to a hostile or apathetic audience. That is because it allows the speaker to focus on the counterarguments the audience brings to the rhetorical occasion before making their appeal. This speech usually consists of three or four main points:

- In the first two to three points, the speaker acknowledges and refutes the strongest opposing arguments or most common solutions to the topic at hand. Each opposing argument and refutation constitutes one main point in the body of the speech.

- In the final main point, the speaker identifies their preferred solution and argues for its superiority.

You might use this arrangement when you expect your audience’s resistance to your proposal will be strong. For example, a speech that calls for an investment in downtown recycling bins in a city that has shown little commitment to recycling might be served well by this pattern of arrangement.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence was developed by Alan H. Monroe, a twentieth-century professor of communication. He based it on the idea that when one feels psychological discomfort, one is motivated to resolve that discomfort through some sort of action. The speaker who employs this sequence typically follows this pattern of five main points:

- Attention step (introduction): Catch the audience’s interest.

- Need step: Convince the audience that something is presently wrong that needs their attention.

- Satisfaction step: Provide the audience with a solution that is within their power to correct the need.

- Visualization step: Let the audience see how the satisfaction step will really change things in the future and/or see how bad things will get if they fail to adopt your method of satisfying the need.

- Action step (conclusion): Ask the audience to participate and do something specific to satisfy the need.

Many commercials follow this effective sequence as well as speeches, as box 13.3 demonstrates.

Box 13.3 Sample Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Arrangement

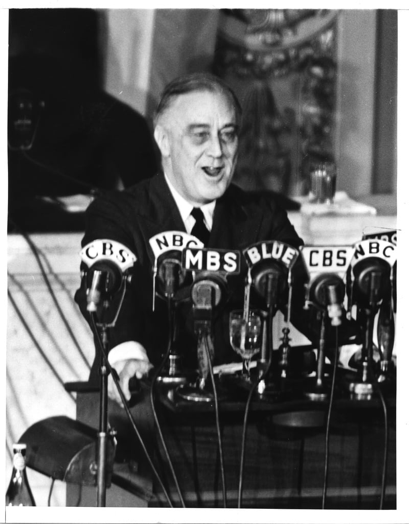

President Franklin Roosevelt’s famous “War Address” is a real-world example largely patterned on Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.[1] He delivered it on December 8, 1941, to a joint session of the US Congress, just one day after Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor and many other sites. This speech marked the United States’ entrance into World War II.

- Attention step: FDR’s famous opening line caught listeners’ attention as he described the “infam[ous]” day “America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by the naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

- Need step: FDR went on to explain that the Japanese government “deliberately sought to deceive the United States” by striking while claiming to be at peace with the US. He then specified all the locations that Japanese forces attacked.

- Satisfaction step: FDR built up to stating how the attack will be met: “We will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us.”

- Visualization step: FDR inspired listeners to view the future positively, promising, “We will gain the inevitable triumph” over Japan “so help us God.”

- Action step: FDR ended the speech by asking Congress to “declare” that “a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire” since their December 7 attack.

Nonlinear Patterns of Arrangement

Recall that nonlinear patterns of arrangement adopt a more circuitous or indirect route to, or in support of, a thesis. They place value on vivid stories, examples, and testimony they offer as evidence as much as on the main points (claims) themselves. Next we describe three examples of nonlinear patterns of arrangement: spiral, narrative, and triangle or star.

Spiral

A spiral arrangement utilizes main points that circle around the thesis, building tension and strength along the way.

- The initial main point identifies an aspect of the speech topic that is mildly concerning.

- A middle main point strengthens the magnitude of the issue.

- The final main point focuses on an element that is deeply alarming or greatly impactful for the audience.

The content of the main points can focus on whatever aspects of the topic the speaker finds useful for their audience—such as particular elements of the problem, types of stakeholders or victims, or even contexts or scenarios that illustrate the issue. Typically, the main points should include similar types of content so that their growing intensity or tension is more readily experienced. An advantage to the spiral pattern is its ability to help the audience increasingly feel the urgency, importance, or magnitude of the issue.

Box 13.4 Sample Spiral Arrangement

A speaker advocating to their employer for a

company-wide four-day workweek might organize their main points this way:

company-wide four-day workweek might organize their main points this way:

- Mildly concerning point:

High infrastructure costs of lighting and heating/cooling for a full five days (compared to four days)

High infrastructure costs of lighting and heating/cooling for a full five days (compared to four days) - More worrisome point: The physical and mental health risks related to a five-day week (and the benefits and savings provided by reducing one day)

- Most alarming point: Decreased revenue and higher employee turnover suffered by companies with a five-day workweek (contrasted with higher revenue and lower turnover for a reduced workweek)

Narrative

A narrative pattern tells a single detailed story to compel the audience to accept the speaker’s thesis; that is, the speaker uses the story to illustrate the thesis and make it compelling. Consequently, the main points typically draw on a chronological arrangement by moving audiences through the beginning, middle, and ending moments of the story. The beginning might establish the people, setting, and conflict of the narrative. The middle can emphasize the climax of the story, and the ending might offer resolution. Each main point offers rich details to establish and draw listeners into that part of the story.

While the story form naturally lends itself to testimony and examples, statistics can also be incorporated to support each main point or story moment. For instance, if the story focuses a main point on the major conflict or problem faced in the narrative arc, statistics could be integrated to establish the commonality or impacts of the problem on people like those featured in the story.

A narrative pattern is advantageous because human beings love telling and hearing stories. According to rhetorical studies scholar Walter Fisher, we use stories to make sense of information and to guide our decision-making.[2] Through a well-told story, a speaker can bring a community problem to life and elicit empathy by helping the audience walk in someone else’s shoes. Narratives can emotionally move and compel listeners in ways that cold statistics alone cannot. In addition, a narrative pattern can flex to suit the speaker’s needs. It may alter the audience’s beliefs or attitudes about a problem by focusing the story’s attention on the issue, or it may promote a desired policy by offering it as the resolution to the story. Narrative patterns can also communicate the speaker’s own story or convey the experience of another person or group.

Narrative patterns appear frequently in diverse speaking environments. In some Western religious contexts, for instance, speakers share personal testimonies about their spiritual awakenings to encourage similar kinds of discoveries or conversion for their listeners. In civic contexts, speakers seeking funding for policies and programs share how previous grants helped their clients overcome major obstacles.

Box 13.5 Sample Narrative Pattern of Arrangement

Imagine being the director of a community program that helps adults earn their high school equivalency diploma. If you hope to persuade the city officials to help fund the program, you might use a narrative structure to organize your speech this way:

- Begin the story: Describe a client who dropped out of high school because of childhood trauma and, consequently, could only qualify for low-wage jobs.

- Middle of the story: Explain how, due to generous financial support for your program, the client enrolled for free and pursued their high school equivalency diploma.

- End of the story: Celebrate how the client earned their diploma and now works at a higher-paying job.

You could develop each story point with statistics that establish the broader prevalence of challenges like those faced by this client, the quality of support offered by your program, and the program’s track record of success.

Triangle or Star

A triangle or star arrangement provides multiple main points—like the corners of a triangle or the tips of a star. The main points may appear disparate from each other, but all support the thesis. For instance, one main point may focus on a supporting claim that is particularly exciting, engaging, or entertaining for the audience. Another main point might make a controversial supporting claim, while a third main point may forward a proposition the audience likely already accepts.

We’re calling this a triangle or star only due to the number of main points you need. Many speeches are short and thus are served well by three main points (a triangle). Some presentations, however, are much longer. You might think here of delivering a keynote address at a community event or an educational speech for a civic organization. In these cases, five main points, or the star, may be more useful.

As with a triangle or star, the ordering of the points is flexible. You can rotate a triangle or (a drawing of a) star to the left or right without damaging the form. Similarly, a speaker using either can change the order of main points without damaging the logic of the speech.

Because of such flexibility, a triangle or star pattern can be easily adapted to different audiences and situations—even in the moment. These structures also encourage diversity in the content and tone of main points. Supporting material can range from deeply serious or even controversial to more lighthearted.

Box 13.6 Sample Triangle Pattern of Arrangement

A speaker advocating for their college to widely adopt open educational (i.e., free) resources (OER) might support that thesis with the following three main points (or could add two more points and use a star pattern):

- Serious point: Establish the increasingly expensive costs to students of commercial textbooks.

- Interesting point: Demonstrate the more vivid formatting, pictures, and even online interactive features of some OER books.

- Controversial point: Argue that requiring commercial textbooks exacerbates wealth inequality.

Because of the diversity of supporting material, the thesis plays the satisfying role of anchoring or tying all the main points together—in our example, that would be to widely adopt OER materials. The thesis may be articulated in the introduction to help guide the audience’s understanding of the main points’ connections, or it can be delayed until the conclusion to provide an “a-ha” moment of the speech’s primary claim and goal.

Boxes 13.7 and 13.8 summarize the patterns of arrangement addressed in this section. They list the primary strengths of each pattern of arrangement, offers examples of speech topics that could be potential candidates for this pattern of arrangement, and suggests a possible outline of main points. Ultimately, the pattern of arrangement you choose, and how you outline its main points, should be determined by your primary arguments and your purpose for the speech rather than by our charts.

Box 13.7 Linear Patterns of Arrangement

|

Linear Pattern of Arrangement |

Primary Strengths |

Example Topics |

Possible Basic Outline of Main Points |

|

Categorical |

|

|

|

|

Chronological |

|

|

|

|

Spatial |

|

|

|

|

Cause-effect |

|

|

|

|

Problem-solution |

|

|

|

|

Problem-alternatives-solution |

|

|

|

|

Problem-cause-solution-solvency |

|

|

|

|

Refutative |

|

|

|

|

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence |

|

|

|

Box 13.8 Nonlinear Patterns of Arrangement

|

Nonlinear Pattern of Arrangement |

Primary Strengths |

Example Topics |

Possible Basic Outline of Main Points |

|

Spiral |

|

|

|

|

Narrative |

|

|

|

|

Triangle and star |

|

|

|

As you select an arrangement to organize your speech material, think about which one will help you achieve the desired outcomes of a well-organized speech. More specifically, pick the pattern that will help the audience track your thinking and logic, making it both easy to follow and coherent. Remember to also consider which pattern may engage your audience’s attention because of the interesting connections it suggests between points. Finally, consider your time restraints as you determine the number of main points you can reasonably develop and deliver.

Summary

In this chapter, we focused on a speech’s main points and common patterns of arrangement. More specifically, this chapter covered the following:

- Main points are the major ideas or claims that compose a speech’s body and support the thesis statement.

- Patterns of arrangement can typically be categorized as linear or nonlinear. A linear progression of main points moves in a “straight line”—with one step logically leading to the next—all clearly in support of a thesis that is stated early in the speech. Examples include categorical, chronological, spatial, cause-effect, problem-solution, problem-alternatives-solution, problem-cause-solution-solvency, refutative, and Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

- A nonlinear progression of main points adopts a more circuitous or indirect route to, or in support of, a thesis. Examples include spiral, narrative, and triangle or star patterns of arrangement.

- Main points can be organized according to several patterns of arrangement. Each pattern has its own strengths and is not appropriate for every subject, thesis statement, or audience.

Key Terms

categorical arrangement

cause-effect arrangement

chronological arrangement

linear

main points

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

narrative arrangement

nonlinear

pattern of arrangement

problem-alternatives-solution arrangement

problem-cause-solution-solvency arrangement

problem-solution arrangement

refutative arrangement

spatial arrangement

speech body

spiral arrangement

star arrangement

triangle arrangement

Review Questions

- What are main points?

- How does a linear pattern of organization differ from a nonlinear pattern?

- What are examples of two linear patterns of arrangement and two nonlinear patterns?

Discussion Questions

- Do you tend to prefer linear or nonlinear patterns of arrangement? Why?

- Where are you most likely to hear a speech that is organized linearly? Nonlinearly?

- Find a sample speech and identify its main points. Which pattern of arrangement does it seem to follow?

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Joint Address to Congress Leading to a Declaration of War Against Japan" (transcript, Washington, DC, December 8, 1941), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/joint-address-to-congress-declaration-of-war-against-japan, archived at https://perma.cc/6AJ2-9G7X. ↵

- Walter R. Fisher, “Narration as a Human Communication Paradigm: The Case of Public Moral Argument,” Communication Monographs 51 (1984): 1–22. ↵