34 Ideological Criticism: Rhetorical Artifacts and Historical Context

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Identify a rhetorical artifact suitable for ideological criticism.

- Reconstruct the historical context for the rhetorical artifact.

At the center of ideological criticism is ideology. When you hear that word, what comes to mind? Perhaps you associate it with ideas or beliefs, like those shared by a group. Maybe you think about the kinds of beliefs and values that drive extremist groups like the Ku Klux Klan or Antifa. Or maybe your mind goes to the most recent political conflict between Democrats and Republicans as a clash of ideologies. Or perhaps you’re simply unsure what to think.

In this chapter, we define an ideology as a set of shared beliefs and values that forms an interpretation of the world and suggests appropriate ways to act in it. We all adopt ideologies—not just extremists or political actors. In fact, ideologies are so plentiful and common that we often overlook their influence in our everyday lives. That’s where ideological criticism can be useful. Ideological criticism is a method of rhetorical criticism that exposes the ideology communicated by a rhetorical artifact and interprets how the artifact uses the ideology to exercise power and control.

Ideological criticism aids democratic participation in several ways. It allows you to notice and think critically about communication. That includes recognizing how an artifact expands or contracts civil liberties. When you discover artifacts that restrict participation, ideological criticism provides you the ability to resist and even produce artifacts to counter that work. We’ll more fully explain each of these benefits.

First, by making ideologies visible in rhetorical artifacts, ideological criticism enables you to thoughtfully respond to such messages. Without conducting ideological analysis, you are less likely to notice an artifact’s ideological functions but just as likely to be influenced by them. Ideological criticism helps you recognize and investigate an artifact’s ideological work.

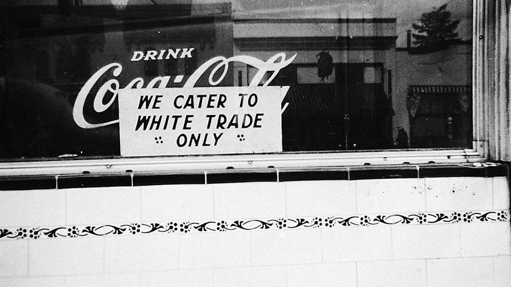

Second, ideological criticism can illuminate how some artifacts communicate ideologies that limit democratic participation. For instance, a Black rhetor—a speaker, singer, or public figure—in the 1950s had few opportunities to participate civically due to the prevailing societal ideology of racial segregation (i.e., racism). That ideology was promoted in numerous artifacts at the time (films, novels, speeches, etc.). Consequently, ideological criticism can sensitize us to see which artifacts contribute to restricting some members of society from fully engaging in public life.

Finally, ideological criticism empowers the public to enact social change. We can resist artifacts that promote ideological messages that inhibit democracy. We can even produce our own rhetorical artifacts that communicate counterideologies that expand and strengthen democratic principles and enhance community engagement.

In this chapter, we will walk you through the first two steps of conducting an ideological critique of your own rhetorical artifact: identifying an appropriate artifact and reconstructing the artifact’s historical context. The next chapter continues with three more steps: describing the artifact’s ideological message, interpreting how the artifact uses the ideology to exercise power and control, and evaluating how the ideology strengthens or weakens democratic principles.

Box 34.1 Ideological Criticism Steps

- Identify an appropriate rhetorical artifact.

- Reconstruct the artifact’s historical context.

- Describe the artifact’s ideological message.

- Interpret how the artifact uses ideology to exercise power and control.

- Evaluate how the artifact’s ideology strengthens or weakens democratic principles.

Identifying a Rhetorical Artifact

The first step of ideological critique is to identify an appropriate rhetorical artifact. Recall from chapters 30 and 31 that a rhetorical artifact is an object of study in rhetorical criticism. It is a specific instance of rhetoric that was produced for an audience at a particular time.

Expressions of ideology pervade nearly every aspect of human society; they are present in our social and religious rituals, our political lives, our intellectual commitments, our economic choices, and our forms of entertainment. This means you might find rich artifacts among advertisements, popular music, social media posts, video games, or political cartoons—just to name a few possibilities.

We have found, though, that artifacts best served by ideological criticism tend to meet the criteria in box 34.2.

Box 34.2 Guidelines for Selecting an Artifact

- Uses verbal, nonverbal, visual, or audio symbols—or a combination.

- Elevates or challenges a common way of seeing the world.

- Attempts to persuade an audience to live or act in a certain way.

- May be familiar to your audience, but your audience has not reflected on its ideological assumptions.

Uses Verbal, Nonverbal, Visual, and/or Audio Symbols

An appropriate rhetorical artifact for ideological criticism can use any combination of verbal, nonverbal, visual, and audio symbols (movies, television episodes, songs, viral videos, commercials, etc.).

Elevates or Challenges a Common Way of Seeing the World

A second criterion to consider for ideological criticism is finding an artifact that elevates or challenges a common way of seeing the world (or both!). Let’s briefly consider each possibility.

Elevates

Many artifacts elevate widely held sets of values and beliefs. Sometimes that ideological work is hard to notice, however, because we’ve become blind to it. Think, for example, of the video game that reinforces militarism or a music video that upholds heteronormativity. Push yourself to observe how everyday artifacts might promote ideological messages.

Challenges

Some artifacts challenge common ways of seeing the world by calling them into question. These may be easier to notice because they “call out” a widely held perspective, such as the example in box 34.3.

Box 34.3 An Artifact That Challenges a Common Way of Seeing the World

Have you seen the pilot episode of AMC’s 2021 television series Kevin Can F**K Himself? It first appears to be a typical sitcom: Kevin McRoberts and his friends are in a brightly lit living room where they tease his wife Allison while we hear canned laughter. However, when Allison leaves the living room, the show quickly becomes a disturbing drama. It focuses on Allison’s pained expressions. It features an ominous soundtrack and dark lighting while using a single camera (as versus the traditional three-camera setup). If the pilot episode was your artifact, it would probably grab your attention! Its scenic contrasts seem to challenge the casual sexism encouraged by sitcoms when women are consistently the butt of the jokes.

Elevates and Challenges

Sometimes artifacts both elevate and resist common ways of seeing the world at once. Consider the example in box 34.4. Such artifacts can provide rich grounds for an ideological criticism, though you must recognize its multiple functions.

Box 34.4 An Artifact That Elevates and Challenges a Common Way of Seeing the World

You have likely seen advertisements for US political candidates that promote American patriotism while challenging the conservatism or liberalism of an opposing candidate. In these cases, a commonly held value (patriotism) is upheld, while a widely held set of beliefs (conservativism or liberalism) is called into question.

The bottom line is that the best choices for ideological criticism are artifacts that reinforce a widely accepted way of seeing the world, challenge that widely accepted way of seeing the world, or both.

Attempts to Persuade

Additionally, identify an artifact that tries to persuade an audience to live and act in a certain way. Such persuasion might appear explicitly or implicitly. A political ad, for example, might

- explicitly critique liberalism by telling viewers the opponent is “a liberal” while writing that word across the screen in large, red letters or

- simultaneously promote patriotism implicitly by showing the candidate dressed in red, white, and blue and standing beside waving American flags.

Steer away from artifacts that are informative or educational in purpose unless you can find implicit persuasive statements related to communal thought or action. Otherwise, you may become frustrated because you can find little about ideology to critique in the artifact.

Familiar but Not Reflected Upon

Finally, you may find it particularly fruitful to look for an artifact you believe is familiar to your audience but that your audience has not yet reflected on its ideological assumptions.

- Perhaps the lyrics of your favorite rap musician are violent toward women, yet you see friends rapping along without thinking about what messages they are coming to view as normal.

- Maybe you notice friends laughing at a particular Super Bowl commercial that presents a newer, more expansive view of masculinity. You might help them look past the humor to see what is compelling in the message.

The key idea is that it’s likely your audience has missed these messages or given little thought or attention to them or the artifacts themselves.

Box 34.5 #IfTheyGunnedMeDown as a Rhetorical Artifact for Ideological Criticism

An example of an appropriate artifact emerged in the days and months following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed eighteen-year-old African American man in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014. Brown was killed by white police officer Darren Wilson in a confrontation on a residential street that had few witnesses and no video footage.

In the days that followed the fatal shooting, tension emerged about how Michael Brown was portrayed in the media:

- His family and friends stressed he was a recent high school graduate and a good kid who was about to begin college classes.

- Police spokespersons, however, released video footage that appeared to show Brown stealing cigars from a convenience store on the morning of his death, and they suggested he had physically attacked the police officer who shot him.[1]

Our rhetorical artifact is a Twitter (now X) campaign under the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown that was most immediately a response to a photo of Brown that NBC News tweeted the day after his shooting.[2] The photo portrayed Brown without a smile, in front of a brick building, with a hand gesture that some have said was a peace sign and others interpreted as a gang sign. In other words, in the photograph, Brown could be read as unfriendly and even aggressive.

Corrected Link: Unarmed Missouri teen killed by officer after ‘physical confrontation’ http://t.co/JITP7e9iJa pic.twitter.com/t4CNLdq6C4

— NBC News (@NBCNews) August 10, 2014

To protest this media representation of Brown, many Twitter (now X) users, particularly young people of color, started tweeting photographs of themselves under the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown. They each posted pairs of photographs of themselves. One photo depicted the subject as partying, smoking, making an offensive hand signal, or looking at the camera in an especially provocative way. In the second photo, the same subject was shown in their military uniform, wearing their graduation cap and gown, caring for their children, smiling or looking friendly, or perhaps reading a story in an elementary classroom. The visual contrasts were striking, and they made powerful statements about the choices news outlets make when they select and publish photographs.

Yes let’s do that: Which photo does the media use if the police shot me down? #IfTheyGunnedMeDown pic.twitter.com/Ng0pUlxWhr

— C.J. Lawrence (@CJLawrenceEsq) August 10, 2014

These photo pairs tweeted for the #IfTheyGunnedMeDown social media campaign meet the criteria for an appropriate artifact for ideological criticism:

- They used verbal and visual symbols by combining two photographs, the hashtag caption, and often a version of the question “Which picture would the media use?”

- They challenged a common way of seeing the world, of viewing news photographs of Black people that are racially biased as unbiased reflections, while elevating another perspective, of the humanity of people of color.

- They clearly attempted to persuade viewers to scrutinize more closely how people of color are represented by the media.

- For audiences who had not previously reflected on images like the one publicly shared of Brown, an ideological critique of the photo pairs would help listeners recognize and consider their ideological messaging.

Reconstructing the Historical Context

Once you have located a suitable artifact, the next step in ideological criticism is to reconstruct the artifact’s historical context. The context helps you understand why the artifact looks and sounds the way it does, which will aid your analysis later. It assists you in recognizing how the artifact was a product of, as well as a participant in, its time, place, and culture.

To determine the artifact’s historical context, find answers to the questions we established in chapter 31: who, why, what, to whom, when, and where? Use box 34.6 for guidance.

Box 34.6 Questions to Ask About Historical Context

- Who was the rhetor for this artifact—that is, the person or entity most invested in how the artifact looks, sounds, and was received by audiences? Is there anything compelling in the rhetor’s biography that led to the creation of this artifact?

- Why was the artifact created? What social, economic, or political realities prompted its creation? If there are earlier or historical references in the artifact, what connection might the rhetor have hoped audiences would see between the past and the artifact’s present?

- What type of artifact was created? What were its major characteristics?

- To whom was the artifact addressed? What visual or textual clues in the artifact hint at the target, implied, and implicated audiences? Whom did it reach? Who was the direct audience, and were they discrete and/or dispersed?

- When was the artifact’s timing? That is, what date was it delivered, produced, or published, and what was occurring politically, socially, or economically that may have influenced audiences’ response to the artifact? How did the artifact compare with or differ from similar types of artifacts that preceded it?

- Where was the artifact’s location? In other words, what was the specific place it was delivered or disseminated, and/or through what medium did it circulate?

“Who?”

Who was the rhetor for the artifact? In previous chapters about rhetorical criticism, we have defined the rhetor as the author(s) or creator(s) of the rhetorical artifact under examination. Depending on the artifact, the rhetor might be obvious. However, artifacts such as photographs, popular songs, video games, or television commercials can make the rhetor harder to pinpoint. Your rhetor may be the photographer, the songwriter, the production team, or the director, for instance. Who was most responsible for the rhetorical artifact’s production?

Who was the rhetor for the artifact? In previous chapters about rhetorical criticism, we have defined the rhetor as the author(s) or creator(s) of the rhetorical artifact under examination. Depending on the artifact, the rhetor might be obvious. However, artifacts such as photographs, popular songs, video games, or television commercials can make the rhetor harder to pinpoint. Your rhetor may be the photographer, the songwriter, the production team, or the director, for instance. Who was most responsible for the rhetorical artifact’s production?

Box 34.7 Rhetors of #IfTheyGunnedMeDown Posts

The rhetors for the #IfTheyGunnedMeDown posts are the Twitter (now X) users who posted pairs of photos of themselves. C. J. Lawrence sparked the trend one day after Brown’s death,[3] but many more X users quickly followed his model.

Having said that, Lawrence’s tweet caught on because it was retweeted by people with large followings, so it’s possible to think of those who retweeted—possibly while adding their own additional messages or photos—as rhetors as well.

The question of “who” the rhetor is can be potentially complicated if you choose social media artifacts, since audience members can resend posts and alter or comment on them (thus, creating a slightly different artifact). Ultimately, think of the rhetor as the person or entity most responsible for the artifact’s creation and intending to influence others’ thinking or behavior.

“Why?” and “What?”

Second, answer “why” by looking for the specific social, economic, or political events that led to the creation or circulation of your rhetorical artifact. This is where you ask why the rhetor made the arguments they did in the ways they did. If possible, unearth the rhetor’s goal. Third, answer “what” by clarifying what type of artifact the rhetor produced in response to the events that prompted it and by naming its major characteristics.

Second, answer “why” by looking for the specific social, economic, or political events that led to the creation or circulation of your rhetorical artifact. This is where you ask why the rhetor made the arguments they did in the ways they did. If possible, unearth the rhetor’s goal. Third, answer “what” by clarifying what type of artifact the rhetor produced in response to the events that prompted it and by naming its major characteristics.

Box 34.8 Prompts for, and an Account of, #IfTheyGunnedMeDown

Why: In an interview about #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, Lawrence—who posted the original tweet—explained his motivation: “The questions began to resonate in my mind that, how are people being convinced that the prey is the predator?…And then I decided that it has to be directly attached to appearance. So I began to think about, what type of social commentary can be jarring to the extent that we can begin to challenge the narrative, that whether I look one way or the other, you cannot capture or embody who I am as a human being on a snapshot.…The point was to disrupt people mentally.”[4]

What: Lawrence created the original social media post and uploaded it to his Twitter (now X) feed. In it, he paired two very different photographs of himself: In the first, he was speaking outdoors at a graduation ceremony with President Clinton laughing in the background. In the second photo, Lawrence was inside a house or apartment, dressed in black and wearing sunglasses while holding up what looks like a liquor bottle. Lawrence paired the photos with the caption, “Yes, let’s do that. Which photo does the media use if the police shot me down? #IfTheyGunnedMeDown.”

Answering “what” is much easier than explaining “why” an artifact was created. If you cannot find a credible source that explains the rhetor’s goal, that’s OK. Knowing the rhetor’s goal is not necessary for ideological criticism. You can, instead, identify the social, economic, or political realities that may have motivated the artifact’s production and circulation. For example, imagine we did not find the interview with Lawrence (highlighted in box 34.8) to identify his goal for #IfTheyGunnedMe Down. Without that, it would be fairly easy to conclude that the social and political contexts for the Twitter (now X) posts were established in reaction to Brown’s death and the ensuing media coverage. Knowing why an artifact was produced can help you notice and later analyze rhetorical features chosen by the rhetor(s).

“To Whom?”

Third, consider who the audience was for the symbolic action. Recall in chapter 10 (and chapter 32) we differentiated the following:

- direct audience (those who are exposed to and attend to the rhetoric)

- target audience (those the rhetor hopes to reach)

- implied audience (those who are represented in the message)

- implicated audience (those who will be affected by the message if it is successful)

We also considered whether the audience is

- discrete (limited to those who show up for an event at a particular day and time) or

- dispersed (unlimited by location and/or time).

Researching and understanding audiences can help you later analyze how the artifact’s ideological messaging might have functioned similarly or differently for each.

Box 34.9 Audiences for #IfTheyGunnedMeDown

Returning to our artifact, #IfTheyGunnedMeDown posts were initially viewed by a dispersed audience of Twitter (now X) users. According to Lawrence, it was fellow members of “Black Twitter”—a vibrant subset that communicates about race-centered issues—who retweeted his post, causing it “to catch a fire.”[5] By the following day, the hashtag had been used so many times—over 168,000[6]—that a Tumblr blog was created to collect the tweets[7] and several major news organizations reported about the hashtag campaign.

Consequently, while the target audience was Twitter (now X) users, the direct audience ultimately encompassed a much wider group of news media consumers and companies. Interestingly, this reach matched the posts’ implied and implicated audiences: the news media (for selecting photographs of the subjects they report), news consumers (to become more aware of these choices), and Black Americans (who too often were depicted negatively by the news media).

“When?”

The next step is to consider the artifact’s timing. In chapter 32, we explained that timing includes both the specific date and time for the artifact and the time period in which the rhetoric was situated.

- What date was the artifact produced, delivered, or published?

- What was happening politically, socially, or economically that may have influenced how audiences responded to the artifact?

- How did the artifact relate to similar types of artifacts that preceded it or to other types of commentary on the issue it addresses?

Understanding how your artifact relates to a broader time period or history of similar artifacts can give you greater awareness of its ideological functions.

Box 34.10 Timing of #IfTheyGunnedMeDown

Brown’s death and NBC News’s tweet with his photograph occurred on August 9, 2013. The next day, tweets using the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown first appeared.

However, we know that NBC’s photograph did not appear in a historical vacuum. Media critics and civil rights activists have long noted that the news media visually portray some minorities—and African American men in particular—with a negative bias. Portrayals of violent or threatening men of color will sell news, this protest contends, and these negative portrayals, in turn, feed cultural perceptions of African American men as dangerous and untrustworthy.[8] As a result, we as media consumers are much more likely to encounter images of African American men as criminals than as teachers, fathers, soldiers, or political leaders.

Given this long-running critique of media portrayals, some Twitter (now X) followers viewed the NBC News–circulated photograph of Brown as yet another occasion where a mainstream news organization chose a threatening-looking photograph of an African American man when they could easily have chosen a photograph that showed Brown smiling or in his graduation cap and gown. As blogger P. J. Vogt wrote, “A photo can be an argument, and the photo NBC News tweeted made a different argument than a more typical victim photo (at a graduation or at home) would have.”[9]

“Where?”

The final element of context to consider is the artifact’s location. In chapter 32, we described location as including both/either the specific place an artifact is delivered or disseminated and/or the medium through which it circulates. The latter can help you determine whether the artifact reached its target audience and who its unintended audiences might have been. Is your artifact a confidential or classified document that was later leaked to the press? If it is a document or film, has it been translated into other languages? Is your artifact a video or internet meme that went viral?

The final element of context to consider is the artifact’s location. In chapter 32, we described location as including both/either the specific place an artifact is delivered or disseminated and/or the medium through which it circulates. The latter can help you determine whether the artifact reached its target audience and who its unintended audiences might have been. Is your artifact a confidential or classified document that was later leaked to the press? If it is a document or film, has it been translated into other languages? Is your artifact a video or internet meme that went viral?

Thinking about circulation will help you consider more fully how ideologies infiltrate cultures. You may begin to explain how certain beliefs or values come to be shared and widely held—or how certain forms of resistance gain wide adherence—when you identify how artifacts spread among groups.

Box 34.11 Location of #IfTheyGunnedMeDown

Twitter (now X) was the medium of communication for the original #IfTheyGunnedMeDown post. According to Lawrence, who produced that post, two Black Twitter users with large followings quickly retweeted his post, which helped it go viral.[10] After that, the tweets began appearing in other social media (resulting in a devoted Tumblr blog) and in many news media reports about the campaign. Eventually several scholars published research on the campaign, often including examples of tweets in their work.[11] We can also include this textbook as a location that is further disseminating the campaign and its original tweet!

Consequently, while the original rhetor distributed his post on Twitter, it—and the tweets that followed—circulated and spread in ways and in places he probably could not have anticipated or imagined. What began as one man’s post to resist racist depictions of African Americans by the news media resulted in a large and well-publicized protest campaign.

When you take time to research your artifact’s historical context—answering who, why, what, to whom, when, and where—you gain important clues. You discover what contributed to the artifact’s production and what it attempted to influence. These clues are invaluable as you describe, interpret, and evaluate the artifact to illuminate its ideological functions. We explain those next steps of ideological criticism in the following chapter.

Summary

As a method of criticism, ideological analysis seeks to understand how a range of rhetorical artifacts shape our understanding and use of ideologies. To provide such understanding, critics using ideological criticism must keep in mind the following concept and steps.

- Ideology is a set of beliefs and values that forms an interpretation of the world and suggests appropriate ways to act in it.

- You begin by identifying a suitable rhetorical artifact. For ideological criticism, such an artifact uses verbal, nonverbal, visual, and/or audio symbols; elevates or challenges a common way of seeing the world; attempts to persuade an audience to live or act in a certain way; and may be familiar to your audience, though they may not have reflected on its ideological assumptions.

- You then reconstruct the historical context for the artifact by discovering what audiences might have known about the rhetor, what prompted the artifact, the rhetor’s likely goal(s), the type of artifact produced, the audience(s) for the artifact, and the artifact’s location and timing.

Key Terms

ideological criticism

ideology

Review Questions

- What is an ideology?

- Describe the characteristics that make a rhetorical artifact a good selection for ideological criticism.

- Which aspects of an artifact’s historical context should you discover?

Discussion Questions

- What might be advantages and challenges of analyzing a rhetorical artifact that mostly uses visual symbols compared to verbal symbols? One that mostly uses audio or nonverbal symbols?

- Is it easier to find rhetorical artifacts that elevate or challenge common ways of seeing the world—or those that do both simultaneously? What are examples of each?

- Are you comfortable conducting an ideological critique if you do not know the rhetor’s goals for the artifact? Why or why not?

- See, for example, Mark Berman and Wesley Lowery, “Police Say Michael Brown Was a Robbery Suspect, Identify Darren Wilson as Officer Who Shot Him,” Washington Post, August 15, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2014/08/15/ferguson-police-releasing-name-of-officer-who-shot-michael-brown/. ↵

- NBC News (@NBCNews), “Unarmed Missouri teen killed by officer after ‘physical confrontation’ nbcnews.to/XaZEd1,” Twitter (now X), August 10, 2014, https://x.com/NBCNews/status/498526729728565250. This post is archived at “Michael Brown’s Death—Image #809, 359,” Know Your Meme, https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/809359-michael-browns-death. ↵

- C.J. Lawrence (@CJLawrenceEsq), “Yes let’s do that: Which photo does the media use if the police shot me down? #IfTheyGunnedMeDown,” Twitter (now X), August 10, 2014, https://x.com/CJLawrenceEsq/status/498537843170353152, archived at https://perma.cc/2GHV-NNGE. ↵

- Ethan Zuckerman, “#iftheygunnedmedown Six Years Later, and Just as Vital—an Interview with Activist C. J. Lawrence,” Ethan Zuckerman (blog), June 5, 2020, https://ethanzuckerman.com/2020/06/05/iftheygunnedmedown-six-years-later-and-just-as-vital-an-interview-with-activist-c-j-lawrence/, archived at https://perma.cc/Z7RC-AMVF. ↵

- Zuckerman, “#iftheygunnedmedown Six Years Later.” ↵

- Tanzina Vega, “Shooting Spurs Hashtag Effort on Stereotypes,” New York Times, August 12, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/13/us/if-they-gunned-me-down-protest-on-twitter.html. ↵

- “If They Gunned Me Down,” Tumblr, August 11-12, 2014, https://iftheygunnedmedown.tumblr.com/, archived at https://perma.cc/2SC5-N9QU. ↵

- For example, see Ronald L. Jackson, Scripting the Black Masculine Body: Identity, Discourse, and Racial Politics in Popular Media (Albany: SUNY Press, 2006); Kirk A. Johnson and Travis L. Dixon, “Change and the Illusion of Change: Evolving Portrayals of Crime News and Blacks in a Major Market,” Howard Journal of Communications 19, no. 2 (2008): 125–143. ↵

- P. J. Vogt, “If They Gunned Me Down,” On the Media Blog, August 11, 2014, https://www.onthemedia.org/story/if-they-gunned-me-down/, archived at https://perma.cc/MC3G-MTMW. ↵

- Zuckerman, “#iftheygunnedmedown Six Years Later.” ↵

- For example, see Christopher R. Campbell, “#IfTheyGunnedMeDown: Postmodern Media Criticism in a Post-Racial World,” in Race and Gender in Electronic Media: Content, Context, Culture, ed. Rebecca Ann Lind (Routledge, 2017), 195–212, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/41387/1/9781138640108_oachapter12.pdf; Roni Jackson, “If They Gunned Me Down and Criming While White: An Examination of Twitter Campaigns Through the Lens of Citizens’ Media,” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 16, no. 3 (2016): 313–19, https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708616634836. ↵