21 Framing and Organizing Deliberative Presentations

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Recognize framing in a public speech.

- Practice deliberative framing for a deliberative presentation.

- Organize a deliberative presentation.

The previous chapter introduced deliberative presentations as a type of informative speech. As we explained, in a deliberative presentation, the speaker strives to fairly and evenhandedly describe a wicked problem and multiple approaches to solving the problem. This presentation prepares a community for a deliberative discussion in which participants examine the problem and approaches to ultimately decide, together, how best to address the issue.

Preparing a deliberative presentation involves five steps. The previous chapter discussed the first three steps: choosing a wicked problem, researching the problem, and discovering a range of approaches that address the problem. This chapter picks up with the fourth and fifth steps: framing and organizing the deliberative presentation. We’ll first explain framing as a rhetorical concept and differentiate persuasive framing from deliberative framing. We will then explain how to frame a deliberative presentation, followed by advising you on how to organize a deliberative presentation. The chapter ends by reflecting on the limitations and benefits of informative speeches.

Framing

Framing refers to the use of language to order and make sense of the world. That is, framing is how we employ language to help shape perceptions of reality. Consequently, you should be conscious of the language you employ when discussing public issues. For any complex and controversial social issue, your words can influence what an audience notices and thinks about, as well as what they overlook or downplay, when drawing conclusions.

The framing of any civic issue typically consists of three parts: It identifies or defines the problem (i.e., what’s wrong), its cause (i.e., who’s to blame), and the solution (i.e., what should be done). Every issue-specific frame includes—and typically promotes—these three elements, whether they are explicitly stated or merely implied.

The framing of any civic issue typically consists of three parts: It identifies or defines the problem (i.e., what’s wrong), its cause (i.e., who’s to blame), and the solution (i.e., what should be done). Every issue-specific frame includes—and typically promotes—these three elements, whether they are explicitly stated or merely implied.

You can use framing strategically when trying to persuade an audience, but framing for deliberation should strive for neutrality and fairness. We’ll explain this distinction next.

Box 21.1 Framing as a Rhetorical Concept

To better understand framing, consider a more typical use of the word. Think about the frames you use to border pictures or pieces of artwork. The size, color, and pattern of a frame can influence what you see or notice in the picture or art itself. Also, choosing what parts of a picture to include inside the frame and what parts to exclude (or crop out) significantly affects what viewers see and notice in the resulting framed image. Discursive framing (i.e., frames created by language) functions similarly.

Persuasive Framing

Different people will frame the same issue differently. Many of our disagreements result from conflicting frames for the same issue. Persuasive framing, then, occurs when a speaker strategically names or defines an issue in a way that sets up their desired outcome as effective and reasonable. Box 21.2 provides examples. Persuasive framing also typically involves stressing the advantages of the speaker’s preferred solution and downplaying or ignoring its drawbacks. We will further explore this type of framing in chapter 25 when we discuss persuasion.

Box 21.2 Sample Persuasive Framing

When it comes to illegal immigration, speakers’ language choices often signify their persuasive framing of the issue. For example, compare two different uses of language to describe unlawful immigration:

- “Illegal aliens” points to immigration as the problem, blames the immigrants for entering the country unlawfully, and typically promotes the solutions of deportation and securing our borders.

- “Undocumented workers” or “unauthorized immigrants” implies the problem is the lack of proper documentation or authorization (such as a certificate of citizenship), blames the long delays and significant costs immigrants face when applying for legal US citizenship, and typically promotes the solution of legislative reform to the citizenship process.

Notice how the problem, cause, and solutions identified in both frames correspond with each other; they compose an internal logic or coherent point of view.

Deliberative Framing

Since deliberative presentations are informative rather than persuasive, a speaker must establish the problem and possible solutions as clearly and neutrally as possible. Deliberative framing, then, occurs when a speaker names or defines the issue in a way all parties can agree upon and encourages the fair and direct comparison of approaches. By adopting deliberative framing, you enhance the audience’s ability to make a group decision about how best to move forward.

Deliberative framing can be tricky, however, because each of the approaches you explore likely offers its own persuasive framing that defines the problem in a way that leads the audience to its preferred solution. Avoid adopting persuasive framings so you can encourage the public to consider more than one way of solving the problem.

How do you do that? We now turn to the work required to successfully frame a wicked problem for deliberation: define the problem fairly, identify the trade-offs of each approach, and specify the value or values that motivate each option.

Defining the Problem Fairly

It is critical that you define the wicked problem fairly; otherwise, the language you use can bias the audience in favor of one of the approaches. To depict the problem fairly, we recommend you adopt a common definition, phrase the problem as a “how” or “what” question, and avoid language used by proponents of any one approach.

First, find a common definition of the problem that all interested parties can agree upon—one that identifies the core issue all the approaches are trying to solve. To do so, you typically want to articulate the problem at a greater level of abstraction or generality than the definition offered by any one of the groups involved. That means presenting the problem as bigger than any specific actor (person, group, organization, or institution) or action. Doing so captures the ultimate focus of all interested parties, invites a variety of perspectives to be expressed, and enables a community to compare them more easily.

Second, phrase the problem as a “how” or “what” question, because these questions invite multiple answers. Avoid using “should,” “does,” or “is” to begin your question because they invite only two sides (for and against, or yes and no).

Finally, avoid language that is used by advocates for any one approach or else the conversation will unfairly favor that preference and unhelpfully narrow the issue. Box 21.3 offers an example of a problem definition that follows these suggestions.

By following these guidelines for defining the problem, no one cause of the problem is stated or clearly implied. Instead, any number of causes could—and should—be identified, revealing the complexity of the wicked problem and opening the door to numerous solutions or approaches as reasonable.

Box 21.3 Defining the Problem for a Deliberative Conversation About School Shootings

To help explain how to define the problem fairly for deliberative framing, let’s take the wicked problem of school shootings. Compare the following appropriate and inappropriate ways of defining the problem and asking about the problem.

Defining the Problem of School Shootings

|

How Should We Define the Problem of School Shootings? |

||

|

YES: Deliberative |

NO: Persuasive |

NO: Persuasive |

|

“incidents where one or more people are injured or killed by a firearm on school grounds” |

“the exploitation of soft targets” |

“the desperate actions of depressed individuals who don’t respond well to life’s stressors” |

|

|

|

Phrasing the Problem as a Question

|

YES: Fair and open-ended |

NO: Overly narrow |

NO: Biased |

|

“How can we best reduce the number of school shootings?” |

“Should schools hire more security officers?” |

“How can we stop people from using military assault weapons to kill schoolchildren?” |

|

“What should we do to decrease school shootings?” |

“Is it acceptable for a school to search students’ backpacks?” |

“How can we stop school shootings without restricting gun ownership?” |

Identifying Trade-Offs

In addition to defining the problem fairly, deliberative framing requires you to identify the trade-offs of every approach.  Trade-offs are the relative advantages and disadvantages that accompany every approach to a wicked problem. Each solution offers certain benefits and drawbacks, prioritizes some people’s needs and neglects or diminishes others, and poses challenges for implementation. Making wise choices requires understanding the drawbacks to each approach as well as the benefits.

Trade-offs are the relative advantages and disadvantages that accompany every approach to a wicked problem. Each solution offers certain benefits and drawbacks, prioritizes some people’s needs and neglects or diminishes others, and poses challenges for implementation. Making wise choices requires understanding the drawbacks to each approach as well as the benefits.

The emphasis on trade-offs contrasts with persuasive framing, which typically only stresses the advantages of the speaker’s preferred solution. Deliberative framing encourages us instead to comprehend that every wicked problem has multiple sides and no magic solution exists—one choice that stands out as the most obvious, that defeats the opposing views, or that will result in 100% agreement.

Box 21.4 Discovering the Trade-Offs of Each Approach

To discover trade-offs, answer the following questions by going back through your research and thinking on your own:

1. What are the benefits of this approach?

-

- What advantages are gained?

- Which stakeholders benefit from this approach, or whose needs are prioritized by this approach?

2. What are the drawbacks of this approach?

-

- What disadvantages are incurred?

- Which stakeholders are hurt by this approach, or whose needs are neglected or devalued? Recognize that a single approach can simultaneously benefit one stakeholder while hurting another.

3. What challenges might arise when implementing this approach?

Example: Returning to the example of school shootings, we can predict that increasing the frequency and realism of security drills at schools would likely mitigate the damage and end a shooting more quickly.

But…

It would simultaneously scare children who experience the drills as if they were real, which could decrease their ability to learn and flourish.

Weighing Competing Values

Further frame your topic for deliberation by identifying the value or set of values that motivates each approach. A value refers to a principle or quality that human beings are committed to and on which they base their thinking and decisions for important issues. Values tend to be central to our self-identity and to our community’s identity.

To understand more clearly how values function in public controversies, we need to establish several principles: (1) we agree generally upon the attraction of basic values, (2) our value hierarchies typically shift from issue to issue and sometimes from case to case, and (3) even when we agree to prioritize the same value for a specific case, we may define or apply the value differently. Let’s briefly explore each principle.

1. We agree generally upon the attraction of basic values, such as loyalty, freedom, and equality. Speakers, however, often imply they support a value (freedom, for instance) while their opponent does not. That is rarely the case.

- Instead, though we agree on most values, we rank them differently. A value hierarchy is a list of values ranked from the most to the least important.

Example: If you and another person create a value hierarchy for equality, responsibility, freedom, family, cooperation, and creativity, you might each, for your own reasons, designate distinct orders. If that occurs with a group of just six values, imagine how much you would diverge when ranking a significantly larger number of the hundreds of values that exist!

- When you and another person prioritize different values, a value dilemma emerges. A value dilemma represents a difficult choice among competing values, especially those associated with policy options.

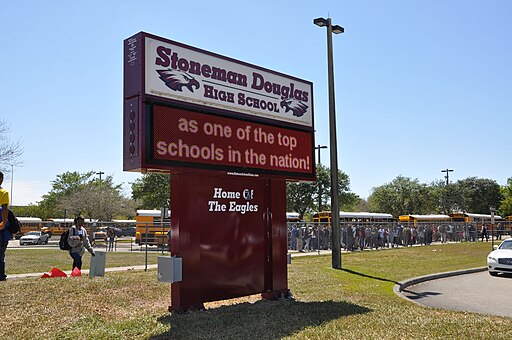

Box 21.5 The Value Dilemma over the School Shooting in Parkland, Florida

On February 14, 2018, Nikolas Cruz walked into his former school, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida, and began shooting. He killed seventeen people and wounded fourteen more. Reactions to this horrific incident reveal the value dilemma it presented as stakeholders prioritized diverse values to address it.

- Security: Scot Peterson, the sheriff’s deputy assigned to protect the school, did not enter the school building during the six-minute massacre. He was charged with (but later acquitted for) child neglect and culpable negligence because of his alleged failure to provide security for the kids.

- Life: Cruz used an AR-15-style semiautomatic weapon to murder classmates. About a month later, on March 24, 2018, survivors of the shooting organized March for Our Lives to protest gun violence and demand legislators pass gun control measures. Florida representatives responded by raising the age required to buy firearms in Florida and passing a “red flag” law to remove guns from potential threats.

- Freedom: The National Rifle Association sued Florida, saying the increased age requirement to own a gun violated the freedom granted in the Second and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution. President Trump made similar comments and called to arm teachers with firearms instead.

- Health: Cruz suffered from depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and autism, leading Trump to comment on Cruz’s mental health. Florida’s legislature increased funding for mental health assistance at schools.

What do you think? Which value(s) would you prioritize to address a US school shooting? How does that choice impact the other values listed here? What other current wicked problems are creating tensions between multiple values?

2. Our value hierarchies typically shift from issue to issue and sometimes from case to case. Changing your value hierarchy does not mean you lack principles or consistency. It simply means you recognize the contingent nature of public controversies.

Example 1: A person who prioritizes “life” in the abortion controversy (and thus opposes most or all abortions) might prioritize justice over life in the case of capital punishment (and thus favor the death penalty even though it means terminating a life).

Example 2: Someone who generally favors capital punishment might oppose it when the criminal has an intellectual disability or is underage, thereby placing fairness (in that these criminals cannot be held fully responsible for their actions) over justice.

3. Even when we agree to prioritize the same value for a specific case, we may define or apply the value differently. Therefore, a speaker should not merely name the value prioritized by an approach but explain how it is defined and applied to the problem.

Example: Regarding school shootings, many people argue that safety is important. But what is considered “safe”? Arming teachers sounds to some like it will increase safety. That same action to others, however, sounds unsafe because of the increased likelihood of accidental shootings and the possible differential treatment by police toward Black teachers who carry a weapon compared to white teachers.

In sum, value dilemmas play a critical role in our conflicts, but too often rhetors speak in ways that hide or simplify them. Part of your job is to help your audience recognize, understand, and ultimately discuss the value dilemmas that undergird their disagreements. Doing so will provide the foundation they need to understand their conflicts and find creative ways to move forward together. But how can you present your findings and information in ways that facilitate such progress? We turn next to the final step of preparing a deliberative presentation.

Organizing the Deliberative Presentation

For your presentation to serve its purpose, it must also be clearly organized. Refer to chapters 12 through 14 to recall why clear organization is important, how to organize main points, and how to develop an introduction, conclusion, and transitions. Here we will suggest ways to tailor an introduction, main points, and conclusion for a deliberative presentation.

In addition to an attention-getter, the introduction might include a central idea (rather than a thesis statement). For a deliberative presentation, your central idea should name the wicked problem as a “what” or “how” question since this question is the presentation’s focus. Your introduction might also include a preview statement that indicates the main points or sections. See Appendix A for an example of these suggestions.

You may find it useful to structure your main points using the problem-alternatives-solution pattern of arrangement discussed in chapter 13 without the solution step included. That means the body of a deliberative presentation could include four main points:

- one main point that explains the problem and

- a main point devoted to each of the three approaches explained. These are the options or alternatives offered for the audience to compare and contrast.

- Notice there is no main point focused on a preferred solution, since that would make the speech persuasive rather than deliberative in nature.

The main points devoted to the approaches could explain the logic of each approach in addressing the problem, its benefits and drawbacks, and the value(s) it prioritizes.

You can conclude by restating the wicked problem and three perspectives and inviting the audience to engage the information you provided through a deliberative discussion.

Box 21.6 Deliberative Presentation Media

A deliberative presentation can be delivered through at least three different media:

- A speech delivered by an individual or group of people. Often the same person or people who deliver the speech then function as moderators of the deliberative discussion (discussed in chapter 22).

- A short film or video. A video can more easily humanize the issue by including video clips of people affected by the problem and/or people voicing support for each of the approaches.

- A written booklet. The National Issues Forum has made what it (and now others) call “issue books” popular. Such booklets are typically concise, yet dense, explanations of a wicked problem and three approaches, though their precise format varies.

Of course, a deliberative presentation can be delivered with two or more of the media listed. Some deliberation practitioners, for instance, provide an issue book to the public in advance of a deliberative discussion and then show a short video right before the discussion to remind them of the options and to educate anyone who did not read the booklet.

Ultimately, creating a deliberative presentation using the five steps outlined in this and the previous chapter will help you prepare an audience for a deliberative discussion. A successful deliberative presentation in any form helps create an environment in which participants are able and willing to listen to each other.

Limitations and Benefits of Informative Speaking

Informative speaking can empower ordinary people to participate in public concerns more knowledgably and actively. However, if done poorly, informative speaking can leave an audience confused, overwhelmed, and even less likely to become active in civic affairs. You might think of a speech you heard that simply regurgitated piles of information. Maybe the speaker stated statistic after statistic, or maybe they simply compiled a list of facts or quotations. The speaker needed to help the audience make sense of the information, such as by clearly organizing the speech and more effectively explaining how the pieces of information related to each other.

Informative speaking can empower ordinary people to participate in public concerns more knowledgably and actively. However, if done poorly, informative speaking can leave an audience confused, overwhelmed, and even less likely to become active in civic affairs. You might think of a speech you heard that simply regurgitated piles of information. Maybe the speaker stated statistic after statistic, or maybe they simply compiled a list of facts or quotations. The speaker needed to help the audience make sense of the information, such as by clearly organizing the speech and more effectively explaining how the pieces of information related to each other.

Informative speaking can also manipulate or constrain an audience. When dishonestly developed, a speech can disguise itself as educational when it actually promotes a particular viewpoint, solution, or action. We might think of the example of infomercials, so called for presenting themselves as informative programs but functioning as commercials to sell products. Audiences must always be wary of informative speeches that rely on biased sources, fail to provide more than one perspective, present overly simplistic depictions of alternative viewpoints, or identify only the positive points of a perspective.

Informative speaking can also manipulate or constrain an audience. When dishonestly developed, a speech can disguise itself as educational when it actually promotes a particular viewpoint, solution, or action. We might think of the example of infomercials, so called for presenting themselves as informative programs but functioning as commercials to sell products. Audiences must always be wary of informative speeches that rely on biased sources, fail to provide more than one perspective, present overly simplistic depictions of alternative viewpoints, or identify only the positive points of a perspective.

Even given these limitations, the benefits of informative speaking in general and deliberative presentations in particular far outweigh the dangers. Well-researched, fair, and balanced informative speeches equip ordinary community members to take an active and influential role in civic affairs.

Summary

The process of forming a deliberative presentation involves the steps of framing the topic for deliberation and organizing the presentation. Specifically, the chapter covered the following:

- Framing is the use of language to make sense and shape perceptions of the world. The framing of any civic issue typically consists of three parts: It identifies or defines the problem, its cause, and the solution.

- Deliberative framing of a problem requires a speaker to fairly define the problem so all parties agree with its characterization, identify trade-offs for every approach, and identify the competing values among the approaches.

- Organizing a deliberative presentation is likely to draw on the problem-alternatives-solution pattern of reasoning without the solution step included.

- If done poorly, informative speaking can endanger civic engagement by overwhelming or confusing an audience. If presented dishonestly, informative speaking can actually advocate a particular solution or perspective.

Key Terms

deliberative framing

framing

persuasive framing

trade-off

value

value dilemma

value hierarchy

Review Questions

- What is deliberative framing, and what does it entail?

- How should you organize a deliberative presentation?

- What are the limitations of informative speaking?

Discussion Questions

- Choose a wicked problem. Find or invent a way to frame the issue persuasively. Now apply deliberative framing. Which is easier to construct? Why?

- Is it ever truly possible to define a problem in a way that everyone agrees? Are there any disadvantages of doing that?

- How might a speaker claim to inform the audience but actually, and perhaps subtly, attempt to persuade them instead?