17 Engaging Your Audience Through Delivery and Memory

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Compare and contrast four common modes of delivery.

- Define communication apprehension and identify strategies to manage it.

- Characterize delivery as an individual skill that is situational and constantly evolving.

When most people think about public speaking, they probably focus mostly on delivery and memory. Delivery, as you learned in chapter 1, is how a speaker physically conveys words and ideas, both vocally and nonverbally, to the audience. When a speaker uses an electronic medium of communication, delivery also regards the speaker’s use of televisual elements, such as the camera, lighting, and background, to communicate. We described memory in chapter 1 as how a speaker stores and recalls the information shared in a speech, such as whether and how much they depend on notes.

Delivery and memory are two of the most visible elements of public speaking. Consequently, it’s easy to equate speaking success with animated gestures, energetic volume, and sustained eye contact. These elements do make a difference, and rhetoric teachers have developed principles and practices to use them effectively.

However, delivery and memory should be placed alongside the many other components of public speaking. Indeed, our positioning of delivery and memory in this book—in the middle—underscores their roles as two of many elements of public speaking rather than a primary focus of attention. In other words, don’t place so much focus on your delivery that you neglect your research, audience adaptation, organization, or verbal style.

At the same time, cultivating skills in delivery and memory is very important. If you have ever listened to a speaker say “like” and “you know” after every sentence, or watched them stare at their notes the entire time, or seen them constantly move in and out of the screen’s frame, you understand why. This chapter begins with the goals of speech delivery, followed by a focus on memory and four associated modes of delivery. We then turn to the anxiety that often accompanies speech delivery and offer ways to address it. We conclude by discussing several principles of delivery to keep in mind as you prepare your speech.

Delivery Goals

The ultimate objective of speech delivery is to communicate with your direct audience effectively and clearly. Recall we defined the direct audience in chapter 10 as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech. To that end, effective delivery should achieve three goals: engage this audience, enhance your ideas, and strengthen your credibility.

The ultimate objective of speech delivery is to communicate with your direct audience effectively and clearly. Recall we defined the direct audience in chapter 10 as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech. To that end, effective delivery should achieve three goals: engage this audience, enhance your ideas, and strengthen your credibility.

First, well-executed delivery helps your audience feel connected to you as a speaker and invested in your speech topic. Ineffective delivery may result in disengaging the audience instead.

Second, delivery also supports your speech content without becoming the focus of attention. Poor delivery can distract from your ideas and instead draw attention to your repetitive use of gestures or excessively fast rate of talking.

Finally, delivery aids your credibility with the audience, or ethos. As discussed in previous chapters, ethos refers to an audience’s perceptions of a speaker’s public character or persona. Effective delivery can bolster an audience’s sense of your goodwill, trustworthiness, competence, and dynamism, but poor delivery can undermine their perception of these qualities. Next we discuss four modes of delivery you can use to achieve these goals.

Memory and Modes of Delivery

Again, memory is how one stores and recalls the information that is shared in a speech. That means delivery and memory go hand in hand. Beginning speakers often find that their delivery improves when they increase their ability to remember their material. As with many aspects of public speaking, how we use our memory is dependent on the expectations and constraints of the speaking situation.

Public speaking scholars commonly recognize four modes of delivery, methods by which a speaker delivers their information. Each approach has its merits in particular situations. We begin discussion of modes of delivery by considering an extemporaneous delivery and then address impromptu, memorized, and manuscript deliveries in turn.

Extemporaneous Delivery

In an extemporaneous delivery, a speaker uses trimmed-down notes to recall the speech’s structure, key ideas, and any direct quotations or source citations. We say “trimmed down” because the notes only include the outline structure and prompting words and phrases; they do not include every word you plan to say (unlike a preparation outline discussed in chapter 15). We call these notes a presentation outline and offer fuller instructions in chapter 19.

Because you cannot rely on your notes for exact wording, an extemporaneous delivery demands a sense of spontaneity as you choose most of your language in the moment. You may want to memorize a few ideas with more precision, such as the introduction (including your thesis and preview) and conclusion to help you begin and end the speech smoothly. With the exception of these elements, however, your delivery will vary each time you practice or give the speech. That keeps the speech fresh.

An extemporaneous delivery enables speakers to maintain a more conversational and energetic delivery while connecting with direct audience members. You are less tied to your notes, which allows you to be present in the situation and potentially make eye contact with the audience more easily. The flexibility offered by extemporaneous speaking also allows you to adjust to audience feedback, be that an unexpected audience reaction, a question posed during the speech, or when you detect the need to add or remove material based on audience feedback.

Extemporaneous delivery particularly suits public settings that discuss issues of community importance. In such situations, elements like setting, audience, and the time available for presentation can change without advanced notice. Relatedly, comments made by other participants before your chance to speak may influence what you plan to say or how you say it. This mode of delivery allows you to alter your remarks in the moment. Thus, extemporaneous speaking capitalizes on your advanced preparation while enabling you to respond to the needs of a given situation as they arise.

Box 17.1 Using an Extemporaneous Delivery to Quickly Adapt to the Situation

What would you do if you found out, moments before giving a speech, that you had half the time to speak than you had anticipated? Could you make cuts within seconds? Would your speaking notes easily accommodate those cuts?

Each of your textbook authors has been invited to speak in public settings. In one case, one of us was asked to deliver a twenty-minute presentation at a specific time. Upon arrival, however, she discovered the event was running late and the audience was growing tired. The person running the event told her she’d have ten minutes before the audience had to leave. She had to cut her speech in half to only the most salient points.

Fortunately, she had planned to speak extemporaneously, and her speaking notes consisted of a trimmed-down outline of keywords. That made it fairly easy to make significant adjustments on the fly. She marked out one main point and several subpoints, and she was ready to go. The audience likely never knew how drastically she changed her plan because of the flexibility an extemporaneous delivery provided her.

Impromptu Delivery

You have probably heard of the mode of delivery frequently called impromptu speaking. In an impromptu delivery, you rely on instant recall because it refers to a situation in which you speak publicly without advance preparation or warning. Your delivery is integrally linked to what you can recall and articulate about a topic on the spot.

This form of speaking comes with a rush of adrenaline as you either are thrust unexpectedly into a speaking situation or feel compelled to suddenly, voluntarily enter a discussion of an issue. As such, it is a reactionary form of speaking, often characterized by high energy and spontaneity while featuring less polish and being more prone to vocal fillers.

Due to the lack of preparation, you may feel more anxiety and pressure with impromptu speaking. Almost inevitably when looking back later, you will think of things you wish you had said. Impromptu speaking challenges even seasoned speakers.

While impromptu speaking prevents formal preparation, you can adopt four strategies to speak more effectively: Take a breath, quickly organize your thoughts, mentally prepare, and jot down notes.

First, take a breath! While you will not have time to develop a speech, you can take a moment to collect your thoughts. Write down two or three keywords, each of which might represent a central point or example you want to mention.

Second, remember the organizational principles you learned in chapters 12, 13, and 14 because they are helpful even in impromptu speaking. Begin your remarks by stating your central point, perspective, or position. Follow that with a short series of brief supporting ideas, probably no more than two or three. You might number the ideas or offset them with transitions to keep the points distinct. Where possible, offer detail in support of your claim in the form of specific examples or illustrations. When you conclude, offer a summary of what you have said.

Third, be prepared. That undoubtedly sounds paradoxical, but there are ways you can mentally prepare for the prospect of impromptu speaking. Most importantly, practice ethical listening as discussed in chapter 6. By being present and engaged in a communication setting, listening actively, and being mentally alert, you will be better prepared to speak if desired or called on.

Lastly, have a way of taking notes (pen and paper, tablet, etc.) so you can jot down ideas during the discussion. This too will spark your thinking and allow you to formulate a response or question to contribute to the ongoing dialogue.

Memorized Delivery

As its title suggests, in memorized delivery you memorize the speech word for word with the intent of precisely recalling and delivering its content without the aid of notes or a manuscript. This mode of delivery emphasizes your memory, requiring extensive practice to recall not only ideas but the exact words prepared for the presentation.

As you can imagine, effective memorized speaking is difficult, particularly for lengthy presentations. It also comes with substantial risks, including “blanking” on what you plan to say, needing to rebound from a lapse in memory, and finding the flexibility necessary to adapt to a challenging situation or adverse audience feedback.

Box 17.2 Disadvantages of a Memorized Delivery

Have you ever tried to memorize a lengthy text? One of your textbook authors competed in their high school’s speech and debate club. They researched, wrote, and frequently delivered a ten-minute informative speech completely from memory, with no notes! That feat was impressive when they succeeded. On one occasion, however, they suddenly lost their place about four minutes into the speech. Instead of picking up where they stopped, they had to start the speech over—from the very beginning. That was the only way they could recite it fully. Talk about embarrassing!

Have you ever tried to memorize a lengthy text? One of your textbook authors competed in their high school’s speech and debate club. They researched, wrote, and frequently delivered a ten-minute informative speech completely from memory, with no notes! That feat was impressive when they succeeded. On one occasion, however, they suddenly lost their place about four minutes into the speech. Instead of picking up where they stopped, they had to start the speech over—from the very beginning. That was the only way they could recite it fully. Talk about embarrassing!

A final concern for memorized speaking is the adoption of a mechanical delivery and a vacant or distant look—one that lessens engagement with the audience—that can result from the strain of recalling the words. This sort of “canned” presentation—one that is fully prepared in advance—can result in the speaker losing touch with the moment during the presentation.

Memorized speaking should be used sparingly, though it can be valuable in particular situations. Crises, for instance, can call for specific, prepared language that informs or comforts a community. A memorized delivery in these cases allows the speaker to visually connect with listeners instead of looking down at a manuscript. It also prevents the speaker from inadvertently saying something that prompts additional uncertainty or harm.

Speeches given routinely may also benefit from memorization, such as a university campus tour speech, because the guides can look where they are walking while still providing all the details each tour group seeks. If you deliver a memorized speech, allow plenty of time to commit the speech to memory and attempt to do at least one full rehearsal with a listener who can provide feedback on your vocal, nonverbal, and—if appropriate—televisual delivery.

Manuscript Delivery

Finally, in manuscript delivery, the speaker writes the entire address in advance and utilizes the text in delivering the speech. Depending on the technology available (e.g., a teleprompter, video conference), the use of a manuscript may not be readily apparent.

A skilled manuscript speaker achieves the goals of an effective delivery. That is, they engage the audience, enhance their ideas, and strengthen their credibility. Such success requires preparing your manuscript in ways that free you from monotonously reading your text. We provide tips for preparing a manuscript in chapter 19.

Manuscript speaking is best suited to formal situations with a large direct audience. This includes formal platform speaking and some televised or recorded speeches with a large viewership. Manuscript speaking also aids occasions where precise wording matters and you have given particular attention to the artistry and style of the speech. Finally, manuscript speeches are common for lengthy addresses. They have the advantage of letting you know more precisely how long your speech will take to deliver.

Box 17.3 Amanda Gorman’s Manuscript Delivery

It takes real skill and practice to effectively deliver a manuscript speech, and it should not be envisioned as simply reading to the audience. Amanda Gorman’s presentation of her poem “The Hill We Climb” at President Biden’s 2021 inauguration ceremony offers a particularly strong example of a well-delivered manuscript presentation. She powerfully drew on such vocal and nonverbal delivery techniques as eye contact, gestures, rate, and the strategic use of intonation and pronunciation to enhance her recitation of the poem. Her delivery helped animate the poem’s artistry and sense of urgency, making her performance one of the most talked about moments from the inauguration.

Every mode of delivery offers both opportunities and constraints. We encourage you to make a thoughtful choice based on your speaking situation, audience, and personal comfort and strengths. Whatever mode of delivery you choose, you will likely experience some degree of nervousness and anxiety. We turn to that challenge next.

Box 17.4 Choosing a Mode of Delivery for Civic Engagement

Opportunities to speak in your community can greatly differ by audience, situation, location, medium, timing, occasion, and purpose. It’s important you choose a mode of delivery that best suits each opportunity, features your strengths as a speaker, and aids your purpose. The following are a few potential civic speaking engagements to help you reflect on available modes of delivery.

- Meeting or public event organized by a civic organization or group: An extemporaneous delivery is ideal if you are invited in advance to address the group, but you will need to rely on an impromptu approach if you are spontaneously asked or suddenly decide to comment. If you are speaking at an event where you will interact with the broader public, an impromptu delivery can provide you with maximum flexibility while keeping a few talking points in mind.

- Ceremonial gathering (dedication, celebration, memorial): For a large, formal ceremonial gathering, a manuscript or memorized delivery will enable you to carefully plan your comments for the occasion and do so with a thoughtful use of verbal style. Choosing between using a manuscript or memorizing your comments may depend on your personal preference and the audience’s expectations. If the gathering is a bit more casual, then an extemporaneous approach can give you more flexibility and informality in your delivery.

- Protest, march, or rally: If you are helping to lead a protest, march, or rally and plan to address attendees at a particular moment, a memorized delivery can ensure you communicate your message precisely while maintaining a visible connection with participants. An impromptu approach may be required if you are suddenly called on to address attendees.

- Publicity for a community event: An extemporaneous or manuscript delivery can work well to share specific information about an event, such as when invited as a guest on a local radio station or when recording a podcast.

Communication Apprehension

Don’t panic. It sounds easy, but we know it can be a challenge. The fear or anxiety that arises when you anticipate public speaking is referred to as communication apprehension. Most people know it as “stage fright.” Such feelings of anxiety emerge for many reasons. You may feel general nervousness about being in front of public audiences or feel stress over the importance of a particular situation. Perhaps you are poorly prepared, feel uneasy about the subject matter, worry about the audience’s reaction, or fear failure. No matter how much preparation this textbook provides, you will ultimately have to navigate a variety of feelings to deliver a speech.

There is good news. Nervousness before, and even during, the act of public speaking is normal. You are not strange or alone in experiencing communication apprehension, and the practices promoted in this chapter can help mitigate its effects. Also, remember that your audience will want you to succeed, especially if you are all in a public speaking class together. They are “rooting” for you because they feel nervous about speaking too. Also, seeing a speaker deliver a speech comfortably makes the audience more comfortable as well.

Box 17.5 Common Symptoms of Communication Apprehension

- feeling that your heart is “racing”

- perspiring

- shaking or trembling

- having a dry mouth

- feeling a “knot” in your stomach

- having a slight sense of nausea

- mind going “blank” while speaking

- swaying

- pacing

- reading speech

- gripping lectern

- having hands in pockets

- folding arms and “hugging” oneself

- speaking too quickly

- fidgeting

- frequently touching face and hair

These symptoms may be manifestations of your speech anxiety. Even when they are not, these behaviors reflect conduct that audiences can perceive as signs of anxiety, regardless of how you actually feel.

The best way to manage communication apprehension is to focus on the skills and preparation techniques described in this textbook. Experience is also an antidote; your level of speech anxiety will likely decrease naturally over time. Still, you are unlikely to completely eliminate speech anxiety—and that can even work to your advantage. An absolute lack of anxiety can actually cause a speaker to sound bored or flat to an audience. In contrast, the energy and passion conveyed by the slightly anxious speaker can encourage the audience to assume the speech topic must be worthy of excitement.

Strategies to Use Prior to a Speech

Some of the most effective techniques for responding to communication apprehension are the preparation practices discussed earlier in this book: researching your topic thoroughly, analyzing your audience, constructing a sound outline, and familiarizing yourself with the speech’s location or medium. These steps will give you confidence as you anticipate what to expect.

You can further reduce communication apprehension prior to your speech if you do the following:

- Learn your introduction particularly well, helping to make sure the speech starts smoothly.

- Practice the speech several times. You might consider working with a speaker’s lab, speech tutor, or friend to help identify and limit any distracting physical mannerisms or signs of anxiety.

- Remember to relax or unwind in advance of the speech. Rather than enter the speaking situation tense and on edge, take a little time for yourself, be that by practicing meditation, engaging in light exercise, working on a logic game, or undertaking another activity that you enjoy and releases tension.

- Visualize yourself giving a successful speech. Close your eyes. Then imagine yourself walking to the front of your classroom or turning on your camera and delivering your speech confidently while interested audience members smile and nod their heads. It may sound silly, but positive visualization can strengthen your confidence by mentally going through the motions.

- If you have the option to deliver your speech as a prerecorded presentation, consider doing so. Prerecording requires significant time to set up, record, edit, and convert into a file or URL you can easily share. However, it allows you to watch yourself and rerecord until you are happy with the outcome. That option can be particularly advantageous for speakers who greatly struggle with communication anxiety as well as those who have a speech impediment or for whom English is a second language.

Box 17.6 Managing Speech Anxiety Associated with Civic Engagement

Civic engagement settings are often more flexible and hence less predictable than other public speaking opportunities. They also more often involve informal, impromptu remarks. Nonetheless, there are several steps you can take to lessen your anxiety when speaking before a civic group or at a public forum.

- Try to meet the organization’s leaders or forum organizers in advance to ask about the likely audience.

- When speaking in person, visit the location of the meeting in advance to learn about the speaking environment.

- When speaking online, ask the people running the event what communication platform will be used and how.

- If it is a recurring meeting, attend a gathering in advance of your speech to gain an understanding of its normal operation.

- If you are giving a formal presentation, discuss the expectations and constraints with the organizers.

- Speak with people who will attend the meeting or have attended the meeting in the past to gain their insights.

- Plan your remarks in advance, forming a speech outline and notes if it is a formal presentation.

- For less formal situations, fill out note cards identifying key points on the topics you are most interested in and most anticipate raising in discussion.

Strategies to Use During a Speech

You can also employ strategies during the speech to help control your anxiety and limit its visual manifestation. You might try the following:

- Look directly at your audience. It is normal to avoid eye contact when feeling nervous, but if you are able, you may find that looking at your audience—physically sitting in front of you or shown through cameras on a screen—can actually calm your nerves. You’ll likely notice facial expressions that express interest and attention, which may build your confidence.

- Adopt good posture if you are physically able to; avoid leaning on a podium or table. Pulling your shoulders back, lifting your chin, and centering or balancing your weight can make you feel and appear more confident.

- Avoid gripping the podium or table (if either is present), as these behaviors can exacerbate and communicate anxiety.

- Remind yourself to breathe to calm your nerves, perhaps using pauses to catch your breath or even making notations on your speaking notes to assist with this.

- Pause if you notice yourself speaking too quickly or falling into a physical pitfall. Do not draw the audience’s attention to the behavior (“Gosh, I’m really nervous,” or “I guess I’m pacing a lot”). Instead, pause for a moment, take a breath, subtly correct your delivery, and keep going.

- Trust yourself and remember the perfect speech will never be given. Being perfect is an impossible expectation that will only heighten your communication apprehension.

Strategies to Use After a Speech

Just because the speech is over doesn’t mean you should stop working to address speech anxiety. Postspeech reflective exercises will help reduce future anxiety. Soon after your speech, therefore, we recommend the following:

- Take notes on how the speech went. Reflect on the positive elements of the speech while also noting areas you can improve.

- Get reactions from your peers. You are typically your harshest critic. Oftentimes, what feels like obvious signs of speech anxiety to you—the speaker—are barely noticeable to the audience.

- Carefully consider instructor feedback. They will likely highlight strengths to continue into the next speech and suggestions for how to improve weaker areas.

Taking a few steps before, during, and after you speak will help you improve your delivery and reduce your anxiety. Your communication apprehension may further decrease by keeping a few delivery principles in mind.

Delivery Principles

We will end this chapter by inviting you to consider three comforting insights about delivery: (1) no one manner of delivery is right for all speakers, (2) delivery is situational, and (3) your skill in delivery will develop over time.

Find a Delivery That Works for You

You can undoubtedly think of speakers with great deliveries. However, that doesn’t mean you should emulate them. You must find a style of delivery that works for you as an individual. What works for someone like James Charles will not necessarily suit you. What worked for John F. Kennedy or Kamala Harris probably won’t fit you well either. To be effective as a speaker, you must develop a delivery that is consistent with who you are as a person and adapted to your personal capabilities and constraints.

Delivery Is Situational

It might sound logical to think a speaker should always speak with energy and passion, incorporate movement, and smile. However, those behaviors aren’t always appropriate or effective. Instead, vary your delivery based on the dictates of the situation.

Box 17.7 MrBeast’s Many Delivery Styles

Jimmy Donaldson, better known as MrBeast by his over 150 million YouTube subscribers, alters his delivery for his YouTube channels. While his appearance remains largely unchanged, his tone, background, use of eye contact, and distance from the camera varies based on whether he is recording videos for his “MrBeast Gaming” channel, for instance, or his “Beast Philanthropy” channel.

The gaming videos are more casual and relaxed, with attention devoted to the game being played. MrBeast tends to record himself for these videos with headphones on, his head and shoulders imposed onto a screen corner over a moving image of the game he’s playing, and eye contact directed away from viewers (assumed to be on the game itself).

The philanthropy videos are more solemn and serious, so MrBeast typically records himself making eye contact with the camera, showing his upper body, often located on the scene of where he is doing the philanthropy, and adopting a more serious tone.

The contrasts in MrBeast’s deliveries reflect the differences in the public speaking situations he is recording.

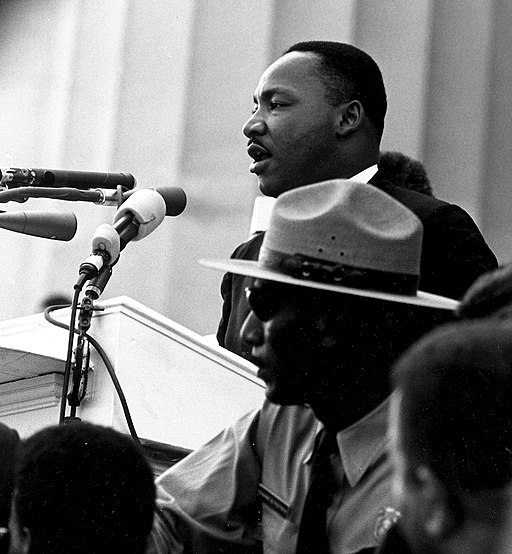

Situational factors such as the speech’s purpose, timing, location, and audience composition and size will require adjustments to your tone, volume, and possible movement (all discussed later in chapter 18). Dr. Martin Luther King’s delivery of his “I Have a Dream” speech is remarkable, but it’s suited to a large audience and significant occasion, not to a boardroom presentation or for a speech honoring the accomplishments of a departing coworker. The situations are different, and so too will be the delivery.

Likewise, conditions such as your immediate physical setting, use of visual aids, and communication medium (in person or through a camera) may constrain the type of delivery you can use. You’ll find suggestions in the next chapter for how to adjust your delivery for a camera, for instance. In chapter 29, we provide guidance for how to deliver your presentation with visual aids in ways that enrich, rather than distract from, your speech.

Your Delivery Will Develop over Time

Finally, realize your delivery will develop over time. As you gain more experience, you will learn what works for you and what does not. You will discover the ideal amount of notes for you, effective and natural gestures or facial expressions, and if you can tell a joke (and when to tell it). When you finish your public speaking class, your delivery will be different than it is now, and it will change again in the months and years ahead. There is always room to improve delivery, even for the best speaker. The target is constantly moving because the subject matter, occasion, audience, available media, and historical moment are also in motion. This is why public speaking is more of an art than a science.

Summary

This chapter addressed the importance of delivery and memory to public speaking. While aiding speech content in important ways, these two concepts are more attuned to issues of form, or how one conveys messages to the audience. Specifically, we observed the following:

- Delivery is a means of engaging the audience, enhancing your message, and bolstering your credibility with the audience.

- Each of the four common modes of delivery—extemporaneous, impromptu, memorized, and manuscript—has its benefits and limitations.

- Communication apprehension, or speech anxiety, is common but can be effectively managed with strategies employed before, during, and after a speech.

- Delivery is a fluid and constantly developing skill that changes over time and according to the situation and personal abilities. With experience you will find a form of delivery that is most natural and comfortable for you.

Key Terms

communication apprehension

extemporaneous delivery

impromptu delivery

manuscript delivery

memorized delivery

modes of delivery

Review Questions

- What is delivery? What is its relationship to memory?

- What are the four common modes of delivery? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each type of speaking?

- What is communication apprehension? What are some common strategies for reducing anxiety?

Discussion Questions

- Why do we heavily focus on delivery and memory in contemporary evaluations of public speakers?

- What about public speaking makes you apprehensive or anxious? What strategies have you used to lessen your anxiety when preparing to speak before an audience?

- Think of a situation in which manuscript delivery would be appropriate. How about a situation when impromptu delivery would be better?