18 Effectively Using Verbal, Nonverbal, and Televisual Delivery

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Identify the most important elements of vocal delivery.

- Assess specific elements of nonverbal delivery.

- Demonstrate the thoughtful use of televisual delivery elements.

The previous chapter established desired outcomes of an effective delivery: engaging the audience, enhancing your message, and strengthening your credibility. This chapter offers three sets of specific tools or techniques to achieve these goals: vocal delivery, nonverbal delivery, and televisual delivery.

Keep in mind that not every speaker is physically, psychologically, neurologically, or culturally comfortable with, or capable of, using every available delivery element. Use the elements that play to your strengths and abilities.

This chapter begins by identifying vocal and nonverbal elements of delivery. We then move to additional televisual components of mediated delivery. Throughout the chapter, we focus on delivering a speech to your direct audience. As defined in chapter 10, these are the people who are exposed to and who attend to your speech.

Vocal Delivery

Vocal delivery refers to how the voice and mouth are used to deliver words. Different vocal techniques can draw the audience into a speech and even encourage audience participation and discussion. Key elements of vocal delivery include volume, tone, rate, pauses, articulation, pronunciation, and avoidance of vocal fillers.

Volume

Volume, or vocal amplification, refers to the loudness of your voice. If you fail to be heard while speaking, nothing else will matter. When determining what volume is reasonable, consider the needs of people who are hard of hearing and may require a louder volume than others. Of course, you should avoid yelling at or overpowering your audience.

Volume, or vocal amplification, refers to the loudness of your voice. If you fail to be heard while speaking, nothing else will matter. When determining what volume is reasonable, consider the needs of people who are hard of hearing and may require a louder volume than others. Of course, you should avoid yelling at or overpowering your audience.

Further volume modification is required based on factors such as the setting, audience size, and type and quality of audio equipment you may be using. Speaking outdoors, which is common for rallies and many civic events, requires more vocal projection to overcome background noise, particularly when a microphone or other amplification is unavailable. The same may hold true when speaking through a screen while sitting in a busy or noisy area. When using a microphone in person or speaking through a screen, test the equipment in advance whenever possible. If you are uncertain about your volume, ask the audience for feedback and adjust accordingly.

Additionally, the size of the audience and your distance from them requires adjustments to your volume. Large and distant audiences demand a louder volume when speaking in person but likely not when addressing them through a screen.

Finally, your volume can also be used strategically. Speaking particularly loudly at key points can reinforce their importance and signal passion for the topic. You can also underscore the significance of information or suggest its sensitivity and confidentiality by using a whisper or drop in voice.

Tone

Vocal tone refers to the sound of your voice or its pitch. You might think of it as the placement of your voice—its highness or lowness—on the musical scale. There is great variety among humans in the tones we adopt for speaking, and you probably have a typical pitch at which you speak. Indeed, most of us naturally stay within a small range of pitches on the musical scale when we speak—that is, most of us speak rather monotonously. Unfortunately, a monotonous pitch can become dull and boring to an audience over time. They may disengage from your message and even wrongly assume you are not excited or passionate about your own message.

Vocal tone refers to the sound of your voice or its pitch. You might think of it as the placement of your voice—its highness or lowness—on the musical scale. There is great variety among humans in the tones we adopt for speaking, and you probably have a typical pitch at which you speak. Indeed, most of us naturally stay within a small range of pitches on the musical scale when we speak—that is, most of us speak rather monotonously. Unfortunately, a monotonous pitch can become dull and boring to an audience over time. They may disengage from your message and even wrongly assume you are not excited or passionate about your own message.

Therefore, if you are able, work on speaking with more variety in your vocal tones over the course of a presentation. You might practice with a friend, at a speech lab, with a speech tutor, or by recording yourself. Focus on occasionally raising and lowering your pitch beyond your typical tone. Consider strategically varying your tone to emphasize particular points or to underscore your thesis, particularly compelling evidence, or your conclusion.

Be mindful, however, to not go too far in strategically timing your intonations or varying them so much that you sound almost robotic or fake. As we mentioned in the previous chapter, an ineffective delivery draws attention to itself rather than enhances the message, and that can occur when speaking too monotonously or too strategically. If you are capable, strive for what we might call a “conversational tone”—that is, a voice that varies in pitch like it might more naturally when you’re having an animated conversation with friends.

Finally, consider how your vocal tone can potentially alter the meaning of what you say. For instance, ending declarative sentences with a higher pitch, like you might when asking a question, can suggest you are unsure of yourself. Using vocal tone to emphasize different words can change the meaning of a word or phrase. Saying “My mom moved to TEXAS in 2020” communicates something different than saying “My mom moved to Texas IN TWENTY TWENTY.” Being aware of how tone can alter meaning is particularly important when leading a public discussion. In a deliberative discussion, as we discuss in chapter 21, one’s vocal tone or pitch should be used to frame topics in a vocally neutral fashion that welcomes diverse participant contributions.

Rate

Rate is the speed at which you speak. You should speak at a pace that is comfortable for you and the audience. In seeking that comfortable rate, be mindful of adopting a speed that is neither too fast nor too slow. If you speak too quickly, the audience will struggle to comprehend the information, particularly more complex material. You also risk overpowering the audience with a rapid-fire style. On the other hand, if you speak too slowly, you might lose the audience’s attention. As listeners, we typically process words faster than a speaker can say them, leaving time for the mind to wander.

Rate is the speed at which you speak. You should speak at a pace that is comfortable for you and the audience. In seeking that comfortable rate, be mindful of adopting a speed that is neither too fast nor too slow. If you speak too quickly, the audience will struggle to comprehend the information, particularly more complex material. You also risk overpowering the audience with a rapid-fire style. On the other hand, if you speak too slowly, you might lose the audience’s attention. As listeners, we typically process words faster than a speaker can say them, leaving time for the mind to wander.

You might selectively increase your rate of delivery when covering less important material. Rate can also be adjusted to add verbal emphasis (slowing down, for instance) or to provide a sense of energy or enthusiasm (increasing your rate at particular points). Changes in rate can be especially effective in situations urging civic action—using your rate to establish urgency and to convey excitement in rallying support for a cause. The takeaway is to vary your rate based on what is comfortable for the audience, the material in your speech, and the occasion.

Pauses

A pause refers to the strategic choice not to speak and to allow a momentary silence instead. Pauses fix the attention of the audience on what you just said, inviting them to ponder an idea for a moment. A pause also allows the audience to catch up with you or to anticipate what you will say next. Additionally, a pause can help indicate a transition, often in conjunction with a verbal signal. However, be mindful of pausing too frequently or at awkward moments. Doing so can make the presentation choppy, result in unintended divisions in content, and create perceptions of nervousness.

A pause refers to the strategic choice not to speak and to allow a momentary silence instead. Pauses fix the attention of the audience on what you just said, inviting them to ponder an idea for a moment. A pause also allows the audience to catch up with you or to anticipate what you will say next. Additionally, a pause can help indicate a transition, often in conjunction with a verbal signal. However, be mindful of pausing too frequently or at awkward moments. Doing so can make the presentation choppy, result in unintended divisions in content, and create perceptions of nervousness.

You can learn to use pauses as a means of incorporating audience feedback and reactions. For instance, if the audience laughs in response to something you say, pause. Otherwise, your next thought will be lost in the laughter. Make similar allowances for audience applause and the occasional “aha” moment when you have made a significant point. Your ability to incorporate such audience feedback will also encourage their participation, whereas talking over their reactions will do the opposite. Practice your presentation with others to help identify moments in your speech that are likely to provoke laughter or applause.

Articulation

Articulation refers to speaking each word with clarity. Poor articulation—mumbling—undermines the clarity of a speech. If you struggle with articulation, try monitoring your speaking rate. When you speak too quickly, you risk running words together, thereby decreasing your clarity. Articulation is an issue to particularly monitor in settings or venues with poor acoustics or when you are using equipment with poor sound quality. In such situations, clear articulation, a slow rate, and purposeful volume will increase your clarity.

Articulation refers to speaking each word with clarity. Poor articulation—mumbling—undermines the clarity of a speech. If you struggle with articulation, try monitoring your speaking rate. When you speak too quickly, you risk running words together, thereby decreasing your clarity. Articulation is an issue to particularly monitor in settings or venues with poor acoustics or when you are using equipment with poor sound quality. In such situations, clear articulation, a slow rate, and purposeful volume will increase your clarity.

A facet of articulation called enunciation refers to the fullness of articulation (or lack thereof). Your enunciation can depend on the situation and audience. For instance, some cultures and communities have a shared habit of dropping the endings from words, such as words ending with “ing” (“runnin” instead of “running,” for example) or mashing words together (“gonna” instead of “going to”). If you are a member of a community, already share the habit, and are addressing them, your enunciation may be fitting, depending on the occasion. It may detract from your message, however, if you are addressing a group that enunciates words differently or if you are not a member of that group. Strategically adopting an enunciation you do not typically use can appear fake or manipulative.

Pronunciation

Pronunciation is the way particular words are spoken or given sound. Proper pronunciation shows command of vocabulary, while mispronouncing terms (particularly when done multiple times) may cause an audience to question your understanding of the word or concept. Pronunciation can also be an issue of (dis)respect and (lack of) cultural awareness if we consistently mispronounce a person’s name or cultural custom. Of course, what is considered proper pronunciation can alter based on one’s culture, community, or geographic region. The word “advertisement,” for instance, is pronounced very differently by Americans than by the British. You can adapt your pronunciation to your audience if you can do so in a way that flows comfortably.

Vocal Fillers

Vocal fillers, also called nonfluencies, are sounds (“um” and “er” most prominently) and words (e.g., “like,” “you know,” and even “and”) spoken repetitively that do not add content to a speech. They are typically used due to nervousness, out of habit, or to fill the silence while finding your next words. A few “ums” are understandable, but when used too often, nonfluencies become distracting to the audience, who may begin to anticipate the filler rather than listen to the speech itself. As you practice your speech, try to break yourself of the habit of using vocal fillers. Learn to pause instead, because a small space of silence is much more effective than hearing a nonfluency.

Vocal fillers, also called nonfluencies, are sounds (“um” and “er” most prominently) and words (e.g., “like,” “you know,” and even “and”) spoken repetitively that do not add content to a speech. They are typically used due to nervousness, out of habit, or to fill the silence while finding your next words. A few “ums” are understandable, but when used too often, nonfluencies become distracting to the audience, who may begin to anticipate the filler rather than listen to the speech itself. As you practice your speech, try to break yourself of the habit of using vocal fillers. Learn to pause instead, because a small space of silence is much more effective than hearing a nonfluency.

The conclusions to draw regarding vocal delivery have been addressed in Chapter 17: find a delivery that suits you, remember delivery is situational, and recognize your delivery will develop over time. Your goal is to use your voice to enhance your content and build your credibility while encouraging audience attention. Through practice in front of people or by recording yourself, you can refine your vocal delivery to best achieve your goals.

Box 18.1 Vocal Delivery Elements

- Volume: Vocal amplification

- Tone: Sound of your voice

- Rate: Speed at which you speak

- Pause: Strategic use of momentary silence

- Articulation: Clarity of each word

- Pronunciation: Manner in which particular words are spoken or given sound

- Vocal Fillers: Repetitive sounds and words that do not add content to the speech

Nonverbal Delivery

Nonverbal delivery refers to how the body is used to communicate. The audience reads or interprets nonverbal cues just as they do a speaker’s vocal delivery. Consequently, nonverbal delivery can engage or distract an audience, underscore or undermine the message, and strengthen or weaken the speaker’s credibility. Important nonverbal elements include eye contact, facial expressions, gestures and movement, and appearance.

Eye Contact

We understand that maintaining eye contact—looking into the eyes of your audience members—can be a challenge for reasons ranging from nervousness, to note dependence, to differences in culture, status, and neurology. In some cases, eye contact may be too physically, psychologically, or culturally uncomfortable—or even painful—to maintain, or it may simply be impossible due to sight impairment. We recommend these speakers turn their attention to developing other elements of vocal and nonverbal delivery to effectively present their speeches.

For others, however, consistent eye contact may simply take practice to overcome nervousness or to use speaking notes more effectively. Culturally, most Americans associate eye contact with truthfulness and sincerity, regardless of whether these perceptions are grounded in reality. Maintaining eye contact also helps the audience feel connected with you, and it provides you with an excellent way to gain audience feedback. As we mentioned in the previous chapter, by looking at your audience (whether in person or through their images on a screen), you can notice signs of positive reception that will lessen your anxiety or signals that you need to move on or slow down.

To make meaningful eye contact as you speak in person, try to look at specific people in the audience, establish and hold eye contact with them for several seconds at a time, and then move to someone else. Include people throughout the space rather than concentrating on a particular location where you find one or two familiar, friendly, or interested faces. Similarly, do not direct too much of your eye contact toward a visual aid—keep most of your focus on your audience.

When speaking through a screen, focus your gaze on the camera or cameras. In such instances, looking elsewhere on your screen will make it appear as if you are avoiding eye contact. You can occasionally glance at the images of your audience members, however, to help alleviate anxiety and to receive their nonverbal feedback to your speech.

Finally, whether you are speaking in person or through a screen, avoid constantly looking at your notes, such as by bobbing your head up and down or reading them on the screen. Neither behavior results in meaningful eye contact, which typically requires holding eye contact with a person or the camera for several seconds as you speak.

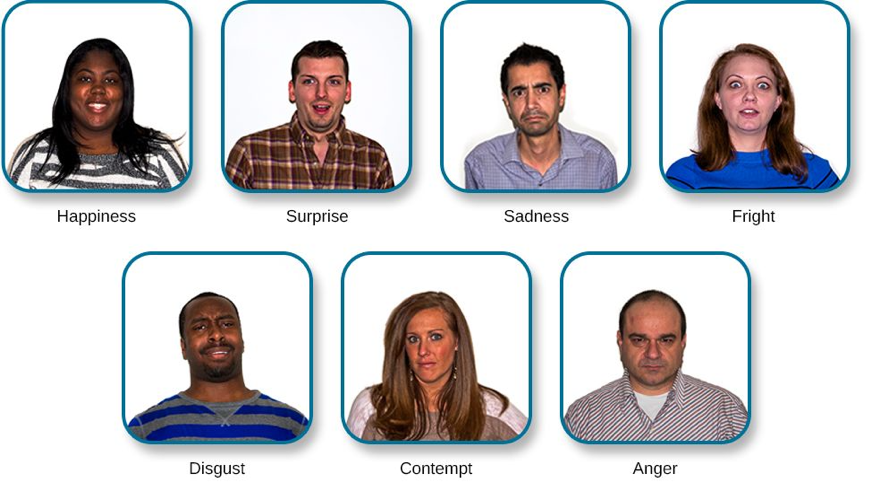

Facial Expressions

One of your most expressive physical attributes can be your face. Taken together with tone, your facial expressions—or use of your face to communicate emotions or reactions—can help clarify the meaning of your message. Think for a moment of how difficult it can be sometimes to interpret an email, text, or post. We are left to wonder if the message is serious or sarcastic, because it lacks the vocal tone and facial expressions that can give it meaning. It’s telling that we’ve developed emoticons and emojis that often feature facial expressions to clarify our meaning. If you are comfortable and able to make a range of facial expressions, then they can be a major asset to your public speaking.

Of course, we also send unintended messages through our facial expressions. As a speaker, think about what message you might send if you never smile during a speech (or if you smile all the time). In a civic context, be mindful of how you interact with other participants through your expressions. You can encourage a participant to contribute or continue talking, for instance, with a warm facial expression or with a nod of the head. In contrast, a flash of anger, a dismissive look (like rolling your eyes), or an expression of frustration may make participants feel less valued or interested in continuing the conversation.

Gestures and Movement

Movement of your hands (gestures) and the positioning and motion of your body (body movement) can both positively impact your speech. While these nonverbal elements are most readily available to uninjured and able-bodied people, many of us can still make use of one or the other. A speaker who is born without arms or loses the ability to use them, for instance, may still be able to walk or alter their posture. A person who cannot stand or move their lower body may be able to gesture with their hands or move a wheelchair while speaking. We encourage each speaker to thoughtfully consider how they may incorporate their available physical motion into their speeches.

Well-placed gestures can draw emphasis to your main points, provide another form of audience engagement, and even assist with transitions. Gestures can also accentuate words by almost physically drawing objects and by illustrating actions. However, repetitive gestures should be avoided, as they are distracting for the audience. Consider leaving your arms relaxed at your sides or on a table when not gesturing. The challenge is to strike an effective balance between random or repetitive gestures on the one hand and overly rehearsed (and thus artificial) gestures on the other.

When offering gestures, think about their visibility, meaning, and situation. If you are standing behind a lectern or sitting at a table, your gestures must be high enough to be seen by the audience. If you are speaking to a large crowd in person, your gestures must be large enough to be visible. If you are speaking through a screen, your gestures must be small enough to be seen within the camera’s frame.

Box 18.2 The Meaning of Gestures

Not all gestures mean the same thing to all people or in every situation. A gesture may be interpreted quite differently across cultures or even over time. In the United States, for instance, the gesture that used to only mean “OK” became widely adopted by white supremacists to promote their racist agenda. In 2019, the Anti–Defamation League classified the “OK” gesture as a symbol of hate. Speakers must be aware of what their gestures might communicate to their audience, given the context.

Along with gestures, a speaker can strategically use body movement to aid the message. When speaking, you might reposition yourself to mark major transitions and to give the audience an opportunity to reset their attention. Such strategic movement can also help you engage different segments of the audience, can possibly release nervous energy, and is much preferred to random pacing.

Another element of movement to consider is body positioning. When talking in person, be cognizant of the physical distance between you and the audience. Situating yourself too close to the audience may make them feel anxious by violating their space. Positioning yourself too far away, such as at the back of a platform or near the back wall, can increase a sense of separation and make you appear uncomfortable. In general, it is best to locate yourself in a central position rather than to the side of the room or speaking platform. If possible, try occasionally repositioning yourself over the course of the speech to ensure all audience members can see you.

Appearance

Appearance regards how you look while speaking. We can control some factors more than others. An element of physical appearance in your control is attire. The way you dress should be fitted to the occasion, the audience, your topic, and you as a person. Dress conveys the formality of the situation and is seen as a sign of speaker competence.

Box 18.3 Looking Presidential

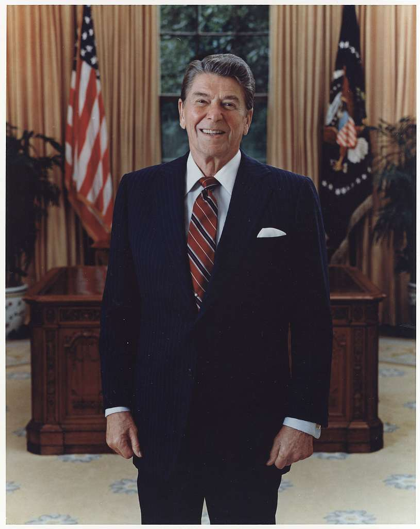

We might look to well-known figures like US presidents to better appreciate the ways your appearance communicates to onlookers.

You may have heard the phrase “looking presidential.” It typically refers to how we expect the US president or presidential candidates to appear in official settings. As the picture of President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office depicts, we typically expect the president to wear a finely tailored suit or dress. Such clothing suggests the president is ready to conduct serious government business.

Contrast that with how presidents generally appear when surveying a disaster site or visiting a more casual setting (e.g., rolled-up sleeves and casual pants). In the other picture, for instance, President Reagan appears on his ranch near Santa Barbara, California, in jeans, a cowboy hat, and a visible belt buckle. His appearance matches the more natural and informal setting, implying he is relaxing and taking time to enjoy his horses.

In both cases, the attire communicates the role the president or presidential candidate is assuming in the situation. Consider what your appearance communicates about your speaking situation and your role in it.

While your classroom speeches are likely fairly casual, think about the perceptions you risk creating if you arrive with your hair standing on end and wearing sweatpants. Your appearance can communicate to your audience that you are not taking the occasion seriously and have not put forethought into your preparation. While your instructor will determine how much that impacts your speech grade, the stakes increase if you dress inappropriately for a job interview, community organization gathering, or public rally. Each of these settings and situations likely calls for very different types of attire; you need to consider that expectation and dress accordingly.

Box 18.4 Nonverbal Delivery Elements

- Eye contact: Looking into the eyes of audience members

- Facial expressions: Use of your face to communicate emotions or reactions

- Gestures: Movement of your hands

- Movement: Positioning and motion of your body

- Appearance: The aspects you can control about how you look while speaking

Televisual Delivery

Many of our speaking opportunities today occur through a screen using videoconferencing platforms such as Apple’s FaceTime, Zoom, Google Meet, or Microsoft Teams, though their popularity and names change over time.

When we present a public speech through a screen, we call that a televisual delivery. Nearly all the vocal and nonverbal elements previously discussed hold importance for a televisual speech delivery, and we have drawn attention earlier to when and how you should adapt those elements for the screen. In what follows, we consider additional delivery components that are unique to a televisual medium: camera framing, angle, and distance; lighting and background; and camera steadiness.

Keep in mind that when you speak through a screen, your televisual delivery may reach different kinds of audiences. As described in chapter 10, if you record and make your speech widely available, your speech may extend beyond a discrete audience (limited to those individuals who show up for your speech event at a particular day and time) to include a dispersed audience (a group of people, unlimited by location or time, who can view your speech). You should consider your speech’s audiences as you use televisual delivery to achieve desired delivery outcomes.

Camera Framing, Angle, and Distance

When speaking through a screen, how you use the camera can influence your speech’s effectiveness. Camera framing refers to the edges of what the camera allows the audience to see and what it cuts out from their visibility. Take time to test what your video presentation looks like for the audience. Typically, you want them to see your full head and shoulders, or possibly also your upper body. Without testing or looking at your framing ahead of time, you may inadvertently display only the top of your head (yes, we have had students do that!) or cut off part of your face, which would distract from your message and likely hurt your credibility.

Your camera’s angle—its slant or viewpoint on the speaker—can also impact what the audience sees and notices. A camera angle that is too high (that looks “down” on the speaker) can focus too much attention on the top of their head and give the sensation of the speaker being small. A camera angle that is too low (that looks “up” at the speaker) tends to draw too much attention to what’s above the speaker (often ceiling lights or fan) and can make the audience feel like we are looking up their nose!

There may be situations in which you strategically adopt a low or high camera angle to accentuate a point or reengage the audience. In general, however, you want the camera more directly in line with your eyes to replicate the experience of talking to someone face-to-face. Doing that focuses attention on your face and generates a sense of connection and equality with your audience. You can accomplish a direct camera angle by raising the height of your electronic device. Stack some books or boxes on a table, for instance. The audience won’t see what you use to raise your device, so it does not have to look good for the camera.

Your camera distance is the length of space between you and your camera. It, too, affects what the audience sees and notices. A far camera distance (also called a long or full shot) enables an audience to see more of your body, gestures, and background, and it may provide space for you to later edit in visual aids if you are prerecording your speech. But it also makes it harder to see your face and thus for you to make meaningful eye contact through the camera. A close camera distance (also called a close-up shot) draws attention to your face and eyes. However, it leaves little room to see gestures, and it can make viewers feel uncomfortable, a little like you are invading their personal space.

Again, you may choose to strategically use shots with a far or close camera distance to meet your delivery goals. Typically, however, as a speaker, you should opt for a medium or medium close-up camera distance that allows viewers to comfortably see your head, shoulders, and upper body from the waist or chest up.

Lighting and Background

Like on any television or movie set, attention should be given to your lighting and background when using a televisual delivery. Both impact what the audience sees and notices, and they can also enhance or hurt your message. Lighting refers to the amount and placement of brightness or darkness on the speaker. When thinking about lighting, try to opt for brightness so it is easier to see your face through the screen. Avoid shadows or uneven lighting when possible.

An inexpensive way to achieve good lighting is by speaking in front of a window on a sunny day. If those conditions are unavailable to you, then you might sit in front of a white or brightly painted wall. Then direct a lamp toward the wall so that light “bounces” off the wall and back onto your face. That indirect approach is typically softer looking than aiming light directly onto you. You might also use two table lamps, perhaps in addition to an overhead light, to better balance the lighting in your space. Relying on an overhead light alone will produce harsh shadows on your face.

Your background refers to everything the audience can see behind or around you within the camera’s frame. To maintain the audience’s attention on your speech, strive to speak in a setting that is quiet both audibly and visually. That is, avoid settings where people may need to walk or move around in the background. Even if they stay silent, their presence will distract the audience.

You may opt for a very simple background, such as in a classroom against a bare wall or even a clean sheet. Alternatively, you may strategically choose your setting to enhance your message. If you are advocating for hunting as a means of environmental conservation, for instance, you might locate yourself in an outdoor setting or adopt a virtual background that replicates the outdoors.

Indeed, virtual backgrounds (and visual effects) are increasingly available and easy to employ. Used strategically or creatively, high-quality backgrounds and effects can enhance your message and strengthen your credibility—and hide a messy room or office. However, many virtual backgrounds and visual effects are of poor quality, excessively busy (e.g., animations, lots of colors), and/or corny. They are more likely to distract viewers from your message and detract from your credibility, especially if the background has no clear connection to your purpose, topic, or occasion.

Camera Steadiness

When televisually delivering a presentation, speakers should be mindful of their camera’s steadiness, or the motion or stillness of the camera’s frame. If you set a laptop on your lap while speaking, for instance, the camera will move around as you gesture and speak (not to mention that your camera angle will be too low). You are unlikely to notice the movement as you speak, but it will be very distracting and possibly uncomfortable for your audience to view. The same may occur if you pound the table on which your electronic device is resting as you speak. To avoid distracting camera movement, place the electronic device on a solid surface and try not to touch that surface while speaking. A desk or folding tray table can work well, especially if you are stacking boxes on top to raise your camera angle.

Box 18.5 Televisual Delivery Elements

- Camera framing: The edges of what the camera allows the audience to see and what it cuts out from their visibility

- Camera angle: Slant or viewpoint of the camera on the speaker

- Camera distance: Length of space between the speaker and the camera

- Lighting: Amount and placement of brightness or darkness on the speaker

- Background: Everything the audience can see behind or around the speaker within the camera’s frame

- Camera steadiness: Motion or stillness of the camera’s frame

Conclusions

Our listing of vocal, nonverbal, and televisual delivery techniques provides a range of considerations for you to make as a speaker. It is important to again recognize that all speaking situations and all speakers are different.

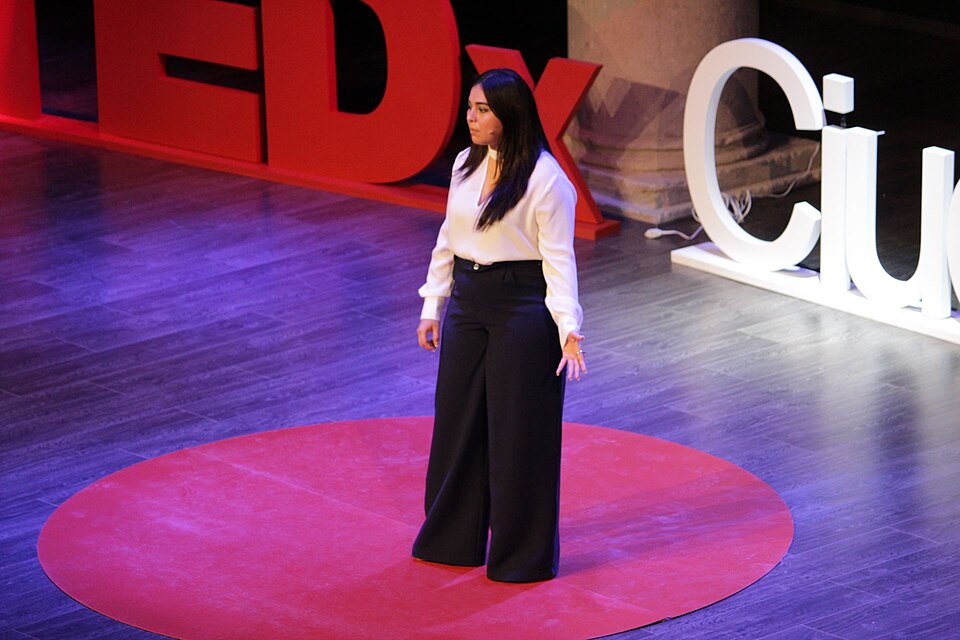

In the end, good delivery helps the audience understand, remember, and act on the speech, and it appropriately suits the situation. Nearly any “TED Talk”—speeches made available online by the nonprofit organization TED—demonstrates the positive effects of a strong delivery. TED Talk speakers typically utilize a range of vocal and nonverbal delivery techniques to successfully engage their audience, enhance their message, and build their credibility. Similarly, many popular YouTubers—people who use YouTube to host their video presentations—model excellent televisual delivery skills in addition to strong vocal and nonverbal deliveries.

Poor delivery, in contrast, can communicate unintended and damaging messages about us as speakers or our attitude toward the audience. Tune into the opening skit (or “cold open”) for any Saturday Night Live television episode, and you’re likely to see the show’s comedians exaggerate the worst delivery elements of the public figures they are parodying. These mocking depictions often imply that the figures have poor morals, low intelligence, or little public appeal. Fortunately, you can use the tools described in this chapter to improve your delivery and aid your public speaking efforts. Remember that experience and practice will help you find the delivery style that works best for you.

Summary

This chapter addressed three sets of tools you can use to achieve an effective delivery. Though not every tool is available for every speaker, each person can use the techniques that play to their speaking strengths. More specifically, we observed the following:

- Vocal delivery, how a speaker uses their voice and mouth to deliver words, is important in engaging an audience. Key elements of vocal delivery include volume, tone, rate, pauses, articulation, pronunciation, and avoidance of vocal fillers.

- Nonverbal delivery, how the body is used to communicate, can enhance or distract from the message. Important nonverbal cues include eye contact, facial expressions, gestures and movement, and appearance.

- Televisual delivery, presenting a speech through a camera and screen, can influence a speech’s effectiveness. Key elements of televisual delivery include camera angle, distance, and framing; lighting and background; and camera steadiness.

Key Terms

appearance

articulation

background

body movement

camera angle

camera distance

camera framing

camera steadiness

enunciation

eye contact

facial expressions

gestures

lighting

nonfluencies

nonverbal delivery

pause

pronunciation

rate

televisual delivery

vocal delivery

vocal filler

vocal tone

volume

Review Questions

- What are important features of vocal delivery that impact the effectiveness of a presentation? How can you adjust these features to benefit your speeches?

- What are important features of nonverbal delivery that impact the effectiveness of a presentation? How can you adjust your nonverbal delivery to increase your connection with the audience?

- What are important features of televisual delivery that impact the effectiveness of a presentation? How can you adjust these elements to enhance your message?

Discussion Questions

- Name three excellent speakers. What makes their delivery effective? How do these speakers differ from one another in terms of their vocal, nonverbal, and (if appropriate) televisual delivery?

- Think of speakers you’ve heard who spoke very poorly. What specific vocal and nonverbal delivery elements hurt their performance? What exactly did they do, and how did it affect you as an audience member? What might they have done differently?

- Recall effective speakers who use a televisual medium almost exclusively, such as popular YouTubers or other influencers. What have you noticed about how they adapt their delivery to the camera and televisual medium?