3 Changing Our Public Communication Toward Productive Discourse

Chapter Objectives

Students will:

- Employ the qualities of productive discourse.

- Assess the difficulty of employing productive discourse.

- Explain the benefits of productive discourse.

How do you, as a democratic participant, improve communication practices? How can you speak in ways that build relationships and contribute to problem-solving rather than polarization? In this chapter, we consider possible solutions. We first rethink public discourse and then introduce specific qualities of productive discourse. We end by considering the difficulties and benefits of productive discourse.

Rethinking Public Discourse

To begin with, we can mentally shift away from equating public discourse with advancing one’s self-interest and defeating oppositional views. We can instead think of public discourse as respectful explorations of disagreement. Such explorations are designed for understanding differing opinions, recognizing our shared identity as a community, and making wise judgments about what is best for the community as a whole.

Box 3.1 Public Discourse as Respectful Exchange

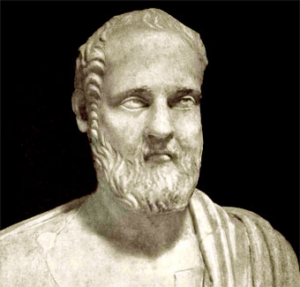

Approaching public discourse as respectful exchange has deep classical roots. Professor of rhetoric Takis Poulakos explains that the ancient Greek teacher of rhetoric Isocrates worked to “disassociate rhetoric from its reputation as a tool for individual self-advancement and to associate rhetoric instead with social interactions and civil exchanges among human beings.”[1] That means we, like Isocrates, can choose how to approach and use rhetoric: for selfish gain or thoughtful exchanges about community issues.

In chapter 1, we explained that rhetoric and democracy developed together in ancient Greece precisely because democracy needs rhetoric to function effectively. We encourage you to think of public discourse as the central tool for facilitating social interactions and common interest rather than self-advancement. Such an approach incentivizes our use of specific productive discourse. We turn next to the qualities that distinguish this type of rhetoric.

Qualities of Productive Discourse

Political theorist Benjamin R. Barber advances “Nine Characteristics of Civility” to encourage public behaviors that will improve democracy.[2] We borrow heavily from his characteristics to outline what we call “productive discourse.”

Productive discourse is public communication that is responsible to one’s community and manages differences constructively. It requires active democratic participation through talking and listening. It reflects sound reasoning. It pursues multilateral problem-solving, and it relies on ethical standards of communication and interaction.

Drawing on Barber’s work, we can identify specific qualities at the core of productive discourse: commonality, deliberation, inclusiveness, provisionality, listening, learning, lateral communication, imagination, and empowerment. To these we add two additional qualities: trust and reliable information. In box 3.2, we briefly paraphrase each of Barber’s qualities of “civil talk”—what we call productive discourse—and then describe our additional qualities.

Box 3.2 Qualities of Productive Discourse

From Benjamin R. Barber[3]

|

Deliberation |

Critically engages arguments and positions rather than the people themselves. Seeks and can accept critique. It can consider multiple solutions rather than a singular focus. |

“That’s an interesting point, but I disagree for these reasons.” “I’ve heard that critique before, and it’s fair.” |

|

Inclusiveness |

Builds discussions that are multivocal rather than two-sided. It seeks dissenting voices and is aware of the many ways voices are silenced in communities and in conversation. It acknowledges variety within a given opinion or position and offers empathy to other participants. |

“My experiences may not be true for others in my position.” “That’s my take, but I’m curious to hear from Geoff.” |

|

Provisionality |

Recognizes that conclusions are never final because ideas, insights, and possibilities will evolve within the process of public discussion. Remains open to further consideration, reflection, and new ideas. |

“I had not thought about that before.” “…but I could be wrong.” |

|

Listening |

Attempts to hear and understand alternative perspectives and to incorporate those perspectives into the whole. Participants are reluctant to interrupt each other, and they reference and directly respond to each other’s points—which helps conversation build momentum. |

“It sounds like you’re saying…Did I get that right?” “I agree with that last point you made, but I see it a little differently.” |

|

Learning |

Seeks to better understand the issues, the multiple perspectives, and the people involved. Participants may change their minds and are willing to make accommodations based on what they hear and learn. |

“That’s interesting. Tell me more.” “Having heard you say that, I now realize…” |

|

Lateral communication |

Originates and evolves among members of the public who talk to each other in spontaneous, unorchestrated settings. As opposed to preferring conversation from leaders and experts, this form of communication circulates among community members and is multidirectional rather than one way. |

“Let’s ask a variety of residents what they view as pressing issues in our town.” “I’m curious how the doctors’ findings on addiction compare with your experience in recovery.” |

|

Imagination |

Offers creative ways of approaching and rethinking the issues at hand. Discourse is marked by impromptu moments, breakthroughs, and/or fresh ideas as opposed to predictable talking points. |

“Hearing you say that just gave me an idea.” “What if we asked the question differently?” |

|

Empowerment |

Enables people to do something positive and effective for the community. Productive discourse is not an end in itself. Its results are collaboration, problem-solving, and the achievement of common goals. |

“If this concerns you, you can…” “Join us afterward for a planning meeting.” |

Our additions

|

Trust |

Assumes general goodwill on the part of participants rather than listening to them with suspicion, assuming they are speaking from a hidden agenda. When we exhibit trust toward others, we are more likely to truly listen to them, to see things we have in common, and to willingly collaborate with them to reach shared goals. |

“That’s a hard but good question.” “I didn’t realize you thought that too!” |

|

Reliable information |

Makes good-faith efforts to provide well-supported claims. Avoids exaggerating or presenting facts out of context in ways that misconstrue their meaning. Backs claims with evidence and shares sources so listeners can evaluate their credibility. |

“This finding holds for small towns but not for larger cities.” “The Wall Street Journal reported on Friday that…” |

Difficulties of Productive Discourse

Have you ever angered someone because you said the wrong thing or expressed a different opinion? Did you wish they would instead try to understand you and show you some grace and compassion? That’s what we must be willing to give each other, especially when we strongly disagree. Unfortunately, few models of such patience and charity exist in the media or our everyday lives. Consequently, while the qualities of productive discourse are easy to list, they can be harder to use.

In addition to curiosity and graciousness, speaking productively also requires time and attention. Compared to unproductive discourse, it is not very exciting. However, if you are willing to devote the time and energy required to learn these skills, then you will discover their numerous benefits.

Benefits of Productive Discourse

Productive discourse benefits civic engagement in at least three ways: It enriches our understanding of complex issues, it unites communities, and it shifts attention to agreeable policies.

To again state the obvious, productive discourse is productive! It produces a richer education about the important issues that affect our lives. You can recognize their complexity and uncertainty and the multiple options available. Such understanding means you can make better, more informed decisions about these pressing issues.

When productive discourse is used, you are more likely to actively address public issues and improve your community rather than watch other people fight it out or make policies for you.

In addition, productive discourse produces a more united community. You are likely to leave an exchange with a more sympathetic understanding of where someone else is coming from and with a stronger sense of what we hold in common.

Finally, productive discourse moves conversations beyond entrenched positions toward mutually agreeable policies. Such outcomes are more likely to motivate you to get involved. Because of its numerous positive outcomes, we consider productive discourse a much more responsible and promising form of communication than unproductive discourse.

Box 3.3 Productive Discourse In Practice

The murder of George Floyd, a Black man, on May 25, 2020, by white Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin helped spark national conversations over racism, policing, and police reform. Just five months later, in November 2020, Black social media personality Emmanuel Acho posted the video “A Conversation with Police” to his popular YouTube series “Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man.”[4] In the video, Acho talked with four white male members of the Petaluma (California) Police Department about racism and policing. Their conversation illustrated several qualities of productive discourse even as they discussed contentious topics.

The conversation featured inclusiveness by involving a range of officers. While Acho was the only Black person visibly present, the officers themselves represented an array of positions and years of experience—differences Acho made clear when introducing and asking questions to each officer and that officers occasionally referenced (e.g., “I’ve been doing this for thirteen years…”). Acho even invited an officer in the live audience to provide his perspective as a traffic officer. By including this range, the conversation revealed a variety of perspectives among the officers and thus avoided dichotomous thinking: Black people versus “the police.” Instead, “the police” became humanized and differentiated across multiple positions, experiences, and viewpoints.

The conversation also displayed inclusiveness by becoming multidirectional. Acho primarily asked the officers questions, but the officers occasionally asked Acho questions as well. For instance, after Officer Ryan McGreevy answered Acho’s question about whether there is “enough accountability in the police force when mistakes happen,” another officer immediately asked Acho, “What does justice look like to you in these situations?” By enabling all participants to ask questions as desired, the conversation was shaped by more than one person or perspective. It also required all participants to potentially be on the “hot seat” and answer questions, not just ask them. Consequently, the discussion included a greater number of topics, perspectives, and experiences than a strict interview format would have allowed.

In addition, all the participants clearly listened to each other. They appeared to make eye contact and nodded their heads as others spoke. No one cut anyone off, and follow-up comments or questions recognized what was previously said. In one instance, retired Officer John Antonio, for example, asked Acho if Black officers make him as nervous as do white officers. As Acho explained why not, Antonio verified he was hearing Acho correctly. Antonio asked if Acho’s connection with Black people “makes you relax a little bit more or…” That check-in allowed Acho to clarify the distinction he was making so Antonio and all viewers could better understand his perspective.

Finally, several participants displayed provisionality rather than certainty in their positions. For example, traffic officer Nick (no last name provided) explained that his officers approach every person at a traffic stop the same way rather than interact differently with Black people (in recognition that the experience can be very different for them than for white people). But he added, “Maybe we should [approach them differently].” Later in the video, when Officer Greely explained why “defunding the police”—such as by allowing mental health workers, rather than police officers, to respond to mental health crisis calls—does not work when a person is wielding a knife, Acho admitted, “I had not heard it like that before.” Such comments displayed humility and open-mindedness as discussants recognized the merits of each other’s points and the limitations of their own understanding. Such provisionality lent to a productive discussion because participants (and, likely, viewers) better understood and respected each other.

Summary

This chapter identified the qualities of productive discourse as well as their numerous benefits for civic engagement. Specifically, in this chapter you learned the following:

- Productive discourse is characterized by commonality, deliberation, inclusiveness, provisionality, listening, learning, lateral communication, imagination, empowerment, trust, and reliable information.

- Models of productive discourse are sparse because such communication requires graciousness, time, and attention, and it is not as exciting to watch as unproductive discourse.

- When utilized, productive discourse enriches our education about important issues, unites us as community members, and shifts our conversations from entrenched positions to mutually agreeable policies.

Key Terms

deliberation

empowerment

imagination

inclusiveness

lateral communication

learning

listening

productive discourse

provisionality

reliable information

trust

Review Questions

- What are the qualities of productive discourse?

- Why is productive discourse difficult to achieve?

- What are three benefits of productive discourse?

Discussion Questions

- Who are examples of public figures who practice productive discourse?

- Is productive discourse an unrealistic expectation? Can you become a civic or political leader using productive discourse? What might you gain or lose?

- Find an example of productive discourse. What specific qualities do the participants display? How so?

- Takis Poulakos, Speaking for the Polis: Isocrates’ Rhetorical Education (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 1, 5. ↵

- Benjamin R. Barber, A Place for Us: How to Make Society Civil and Democracy Strong (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 114–23. ↵

- Barber, A Place for Us, 114–23. ↵

- Emmanuel Acho, host, Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man, episode 9, “A Conversation with the Police," premiered November 1, 2020, YouTube, https://youtube.com/watch?v=pM-HpZQWKT4, archived at https://perma.cc/N8BY-D3HR. ↵