5 Mi universidad

Objectives

Communicative goals

- Ask and answer questions about your field of study and courses.

- Express opinions about classes.

- Give advice to fellow students.

Cultural goals

- Compare and contrast different educational systems and practices.

- Explore educational offerings in other countries.

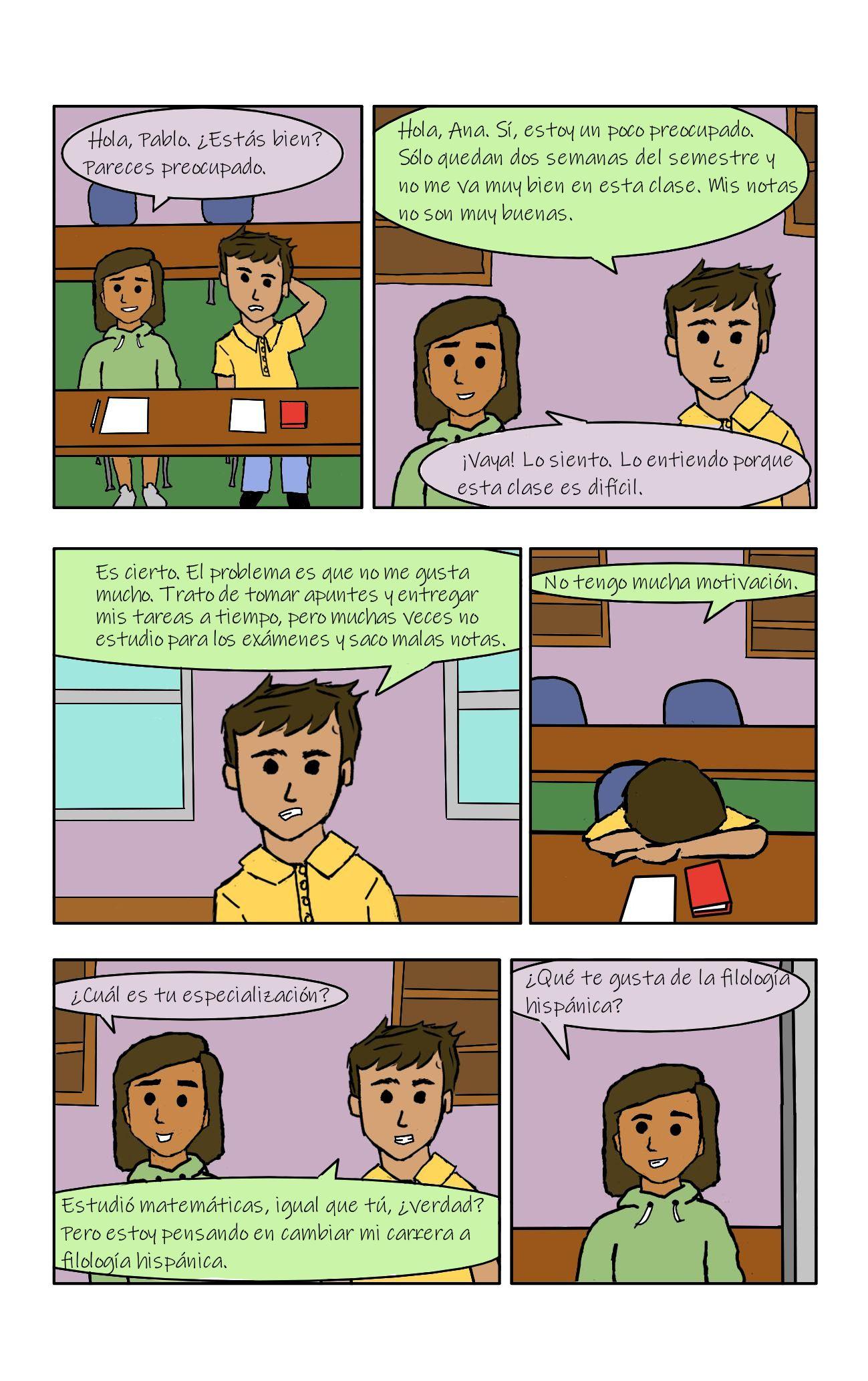

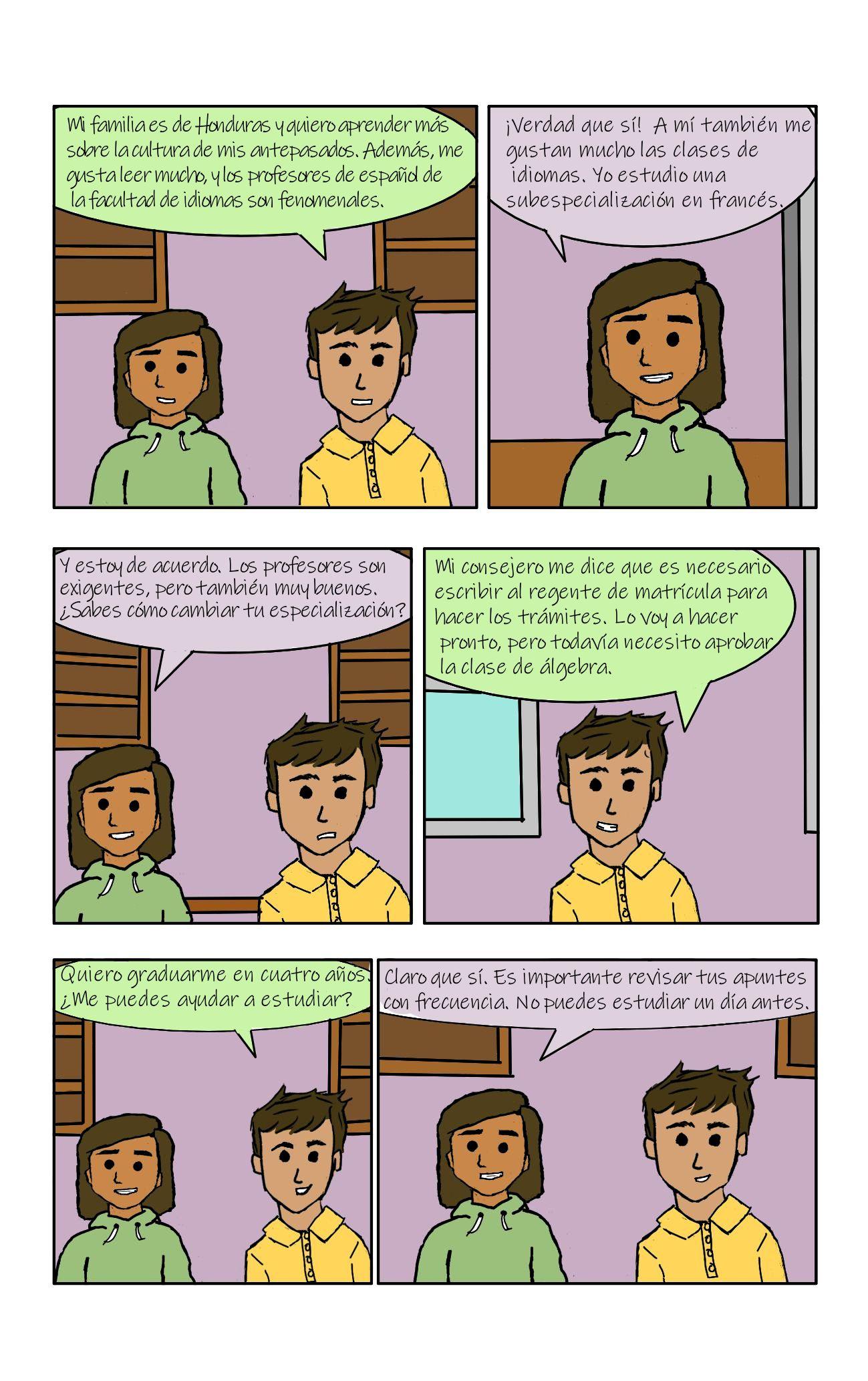

I. Tira cómica

Ana and Pablo discuss their classes and Ana gives advice about how Pablo can do well in math.

Actividad 5.1. Comprensión

II. ¿Te fijaste que…? La educación en el mundo hispano

El sistema escolar

Actividad 5.2. El sistema escolar

Conexión cultural: El sistema escolar

As in the United States, in Spanish-speaking countries, some sort of schooling is required from around the edad de seis años until early teen years, normalmente los quince o dieciséis años. In most places, this educación obligatoria is split into primaria and secundaria, with a few additional years as preparatoria, or more geared toward college or career readiness. In certain countries, como España, the preparatoria years take place in a separate building with a distinct name and course of study.

Depending on the student and the available schools and resources, it is sometimes possible to begin to specialize in the last few years of secondary or preparatory education. While all students study a set of core subjects, called el tronco común, some may begin to take more in-depth or hands-on courses to prepare for college study or a particular career. Students who complete secondary and preparatory study often receive a bachillerato, which tends to be required for entrance into a university and is most often equivalent to an American high school diploma. There is national and regional variation with the term. In Chile, a bachillerato is a two-year university degree and in Costa Rica, students earn a bachiller de educación media before attending university to complete their bachillerato in a specific field of study.[1]

There are many educational terms that, like bachillerato, often represent a false cognate, or a word that sounds similar to a word in a different language but has a substantially different meaning. While bachillerato sounds like “bachelor’s degree,” in most cases, it’s more equivalent to a high school diploma. Similarly, colegio typically—though not exclusively—refers to primary and/or secondary education, not “college” in the sense that in the United States, college refers to an institution of higher education. In certain places, colegio refers to a private rather than public institution, and in others, it is a more common word for escuela, or school. It can also refer to a professional organization, such as Colegio Médico. Meanwhile, the word licenciatura, which sounds like “license,” most commonly refers to a university-level degree but can also be a professional license or even a graduate degree.

Actividad interpretativa 5.3. Similitudes y diferencias

Watch and listen to the video in which Robin discusses some key differences and similarities between Costa Rican and US universities:

Then indicate whether each statement is cierto o falso.

Sistemas de evaluación

Actividad 5.4. Sistemas de evaluación

Conexión cultural: Sistemas de evaluación

What do you think when you hear the words grade, nota, or calificación? In the United States, there are three different systems that work together to determine a student’s level of success: percentage, grade point average (GPA), and most importantly, letter grade. While the percentage equivalent of letter grades varies depending on the institution, program, and even professor, the grade letters A, B, C, D, and F are universally understood in the US to signify a student’s level of achievement.

While terms such as sobresaliente or distinguido (excellent or outstanding); bueno, aprobado, or suficiente (good, pass, or sufficient); and reprobado or suspenso (failed) are used and understood across Spanish-speaking countries, a numerical system of grading is the way to evaluate students. Mexico, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Spain grade 1–10, with 1 being low and 10 high, though the passing grade (usually 5 or 6) varies. In Chile, students are ranked 1–7, with 4 representing a passing grade. Bolivia and Panama rate students out of 100; Venezuela and Peru out of 20; Uruguay out of 12; and Paraguay, Cuba, and Colombia out of 5.[2]

Despite these variations, one constant across Spanish-speaking countries is that the higher the number, the better the score. While this notion is consistent with US grading practices as well, it is by no means universal.

Actividad de reflexión 5.5. ¿Cómo son tus notas?

Answer the following questions in a few complete sentences in Spanish.

- Cuando piensas en tus notas, ¿piensas en una letra (A, B, C, D o F) o un porcentaje? ¿Por qué?

- ¿Qué porcentaje crees que representa las siguientes notas?

a. Sobresaliente

b. Aprobado

c. Suspenso

- ¿Qué notas sacas normalmente? ¿Por qué?

Grade inflation and el examen de admisión

Conexión cultural: Grade inflation and el examen de admisión

In addition to these differences, it is important to note that in the United States, it is much more common to earn extremely high grades. American students often feel immense pressure to maintain a certain GPA or achieve a minimum B+ or A− in their classes. While students in all countries certainly desire to and feel pressure to be successful, how that success is measured varies.

In Spanish-speaking countries, it is much less common to earn extremely high grades such as As or perfect 10s (or 5s, 12s, or 20s). Whereas almost any student who can afford it can attend a college in the United States—if not the most prestigious or with a “full ride”—universities are generally much less expensive but also much more competitive in the Hispanic world.

Students must not only be accepted into the university of their choice but, more importantly, be accepted into the facultad, or school, within the university—think School of Business, School of Nursing, School of Arts, School of History. In order to gain acceptance, prospective students must study for and achieve a high score on a rigorous entrance exam administered by the university or a testing organization, along with meeting other entrance criteria. While standardized college entrance exams are being given increasingly less weight in the United States, with many universities now waiving the requirement for the SAT or ACT, these exams continue to be an integral (and nerve-wracking) part of the college admissions process for students in Spanish-speaking countries. Furthermore, most universities and facultades do not specify a minimum passing grade; students are compared with other prospective students in their cohort, and each group vies for a limited number of spaces. It is not uncommon, therefore, for students to sit more than once for the exam in order to gain entrance to the universidad and facultad of their choosing.

Actividad interpretativa 5.6. La admisión a la universidad en Costa Rica

Watch and listen to the video of Robin discussing how students become accepted to Costa Rican universities:

Then answer the following questions.

La vida universitaria

Actividad interpretativa 5.7. La vida universitaria en Costa Rica

Watch and listen to Robin discuss the cost of Costa Rican universities as compared to universities in the United States:

Then determine whether each statement is cierto o falso.

Conexión cultural: La vida universitaria

Together with differences in the division of educational levels, grading, cost, and competitiveness, there are some fundamental differences in the type of experience students expect from their university studies. You might have noticed an emphasis on the word university or universidad throughout these pages. That’s because institutions of higher education in Spanish-speaking countries tend to be larger, with a focus on both undergraduate and graduate studies and research. This is what distinguishes a university (focus on research, inclusion of graduate programs) from a “college” (smaller, undergraduate only) in the United States.

As has already been mentioned, most universities in Spanish-speaking countries cost a fraction of what it costs to attend an American college or university. For example, in Spain, the average yearly cost for university studies is €1,300, whereas the sticker price for American colleges and universities can easily be ten, twenty, or thirty times higher (or more!) per year. A good portion of these additional costs have to do with the plethora of activities, services, and facilities offered at American colleges and universities. These include student support services, housing and meal services, and special facilities and extracurricular offerings, all of which contribute to the notion of “college life” or “campus life” particular to the US. Of course, not all American students live on campus or participate in the clubs, activities, and organizations offered by their universities. On the other hand, in Spanish-speaking countries, the norm is for students to live and eat at home and go to the university just to attend class. Most universities still do offer student housing for those who for a variety of reasons may need a place to stay, but these students are the minority.

Actividad 5.8. Diferencias y similitudes

Watch the video in which Nicky and Álvaro describe some key differences they have noticed between school and university life in Mexico, Spain, and the United States:

As you listen, write down the things they mention that are consistent with the cultural information you have just read.

III. Ampliación: El papel de la universidad

Actividad de reflexión cultural 5.9. Las perspectivas sobre la universidad

Reflect on your personal cultural perspective about the value and purpose of a college or university education in a complete paragraph. You might consider the following questions to guide your response:

- Do you think everyone should attend college?

- What are the roles and responsibilities of both professors and students at the university?

- Should grades be “curved”? That is, should there be a maximum number of students who receive each letter grade?

- How valuable are tests as a measure of learning compared with other types of assignments such as presentations and projects?

- How important are aspects of “university life” that are not strictly academic—such as sports teams, clubs, or organizations—to the value of a college education?

Actividad 5.10. Cultural comparisons

Read the following two articles by an American student who studied abroad in Argentina and a Spanish student who studied abroad in the United States. Use the below chart to identify distinctive attributes of universities in each country mentioned.

Knoll, Travis. “U.S. Can Learn from Strengths, Weaknesses of Latin American Universities.” Daily Texan, July 11, 2013. https://thedailytexan.com/2013/07/11/us-can-learn-from-strengths-weaknesses-of-latin-american-universities/.

“5 Differences in Universities between Spain and the U.S.” ISEP Study Abroad, June 13, 2019, https://www.isepstudyabroad.org/articles/900

| Argentina | Spain | United States |

Actividad de reflexión cultural 5.11. Cultural perspectives

IV. Vocabulario

| Lugares en la universidad | Places on campus | Áreas de estudio | Areas of study |

| La residencia estudiantil | Dorm

Bookstore Library Cafeteria Stadium Gym Building Classroom Theater Student center |

Enfermería

Inglés (filología) |

Nursing

Chemistry History Biology English Languages Communication Education (primary or secondary) Business administration Sociology Computer science Exercise science Elective course vs. required course |

| Personas de la universidad | People on campus | Más vocabulario | Additional vocabulary related to the college experience |

| El rector | Dean

Registrar President Advisor |

Carrera | Field of study

Bachelor’s degree Major Difficult Easy Scholarship Curriculum Quiz/exam Exam Ask for an extension Change majors Register Drop a class Get good grades Graduate Take notes Grade Transfer Advise Review Turn in Teach Homework Computer Books Notebook Calculator Paper Pen Pencil Backpack |

Actividad 5.12. ¿Qué no se necesita?

Choose the item from the list that will not be helpful in completing the given task.

Modelo:

Tienes un partido de fútbol.

a. Unos zapatos tenis

b. Un cuaderno

c. Una pelota de fútbol

d. Ropa deportiva

Actividad 5.13. ¿Qué debe estudiar?

Read the description of each student and choose the carrera most appropriate for your friend given their likes and dislikes.

Modelo:

A Javier le encanta investigar y aprender sobre el mundo. Le gusta hacer experimentos y trabajar con las manos. No le interesa mucho leer novelas o libros sobre eventos históricos.

a. La historia

b. La química

c. Los negocios

d. La educación

Actividad interpretativa 5.14. ¿Qué clases vas a tomar?

Watch and listen to the video conversation between Mariangel and Jenny and fill out the chart below with the class schedule they decide on for next semester:

Put the subject and who is taking the class. See the example given on the chart, then fill in the following additional classes:

Las matemáticas—Mariangel

La historia—Jenny, Mariangel

El español—Jenny, Mariangel

| lunes | martes | miércoles | jueves | viernes |

| Las matemáticas—Jenny | Las matemáticas—Jenny |

Actividad interpersonal 5.15. ¿Qué clases tienes?

Paso 1—Circle the classes that you have this semester. If there is a class that you have that does not appear on the list, ask your professor for help or look up the term and then write it in the spaces provided.

| Álgebra | Biología | Filosofía |

| Español | Matemáticas | Física |

| Historia | Negocios | Comunicaciones |

| Psicología | Teatro | Seminario de primer año |

| Química | Teología | Sociología |

Paso 2—Answer the following questions in complete sentences.

¿Cuál es tu clase favorita? ¿Por qué te gusta?

¿Cuál es tu clase menos favorita?

Paso 3—Ask a partner about what classes they have this semester, when they are, and which classes they prefer. Try to make the conversation flow naturally by reacting and responding with personal experience or follow-up questions rather than just asking and answering. After the conversation, be prepared to share three things about your classmate’s schedule with the class.

Actividad 5.16. Tus clases preferidas

Answer the questions based on your own perspective.

Modelo:

¿Qué características tienen las clases que no te gustan?

Las clases que no me gustan son aburridas, difíciles o desorganizadas.

- ¿Qué características tienen las clases que te gustan?

- ¿Qué cualidades tienen los buenos profesores?

- ¿Qué cualidades deben tener los estudiantes que reciben becas en tu universidad?

- ¿Cuáles son los aspectos positivos o negativos de asistir a una universidad pequeña? ¿y de una grande?

- ¿Qué facultades son las más populares (tienen más estudiantes) en tu universidad?

Actividad interpretativa 5.17. Estudia en México

Read the following recruitment materials from the Tecnológico de Monterrey and then follow the prompts.

Adaptado de: https://studyinmexico.tec.mx/es?fbclid=IwAR2KWbMO5_94roTvxeudb4Yb9IvR7IAs_ksqPE7DZ9wSA2ugW_CQwf3SK0E.

Diferencia Tec

A través de experiencias educativas formamos a personas que se convierten en agentes de cambio; personas que sean responsables de su propia vida, conscientes que su actuar puede apoyar la transformación de los demás.

Tu experiencia internacional

Vive una experiencia única en México, un país donde siempre te vas a sentir bienvenido, lleno de aventuras y tradiciones mientras desarrollas tus habilidades profesionales en una universidad que te va a permitir liberar todo tu potencial.

Estudia un verano, un semestre o hasta un año académico participando en cualquiera de nuestros muchos programas disponibles para estudiantes internacionales de intercambio y visitantes.

10 razones para estudiar en el Tec de Monterrey

- Asistir a una institución conocida por su excelencia académica

- Toma cursos en inglés, mientras aprendes español

- Aprovecha de modernas instalaciones

- Experimenta una intensa vida estudiantil

- Una universidad multicampus con diferentes ubicaciones para elegir

- Haz amigos procedentes de todo México y el mundo.

- Diversidad de programas—no sólo somos una universidad tecnológica

- México es un país con gran potencial para explorer

- Elija entre una amplia oferta académica para estudiantes internacionales

- Atención y servicios personalizados exclusivamente para estudiantes internacionales

Rankings universitarios

# 155 en el mundo

QS World University 2021

#1 en México

#3 en América Latina

QS Latin America Rankings 2020

#40 en Reputación como empleador

QS Graduate Employability Rankings 2020

Una amplia variedad de opciones académicas para elegir

Escuelas y departamentos académicos

Escuela de Arquitectura, Artes y Diseño

- Arquitectura

- Arte

- Diseño Industrial

Escuela de Ciencias Sociales y Gobierno

- Relaciones Internacionales

- Ciencias Políticas

Escuela de Negocios

- Contabilidad y Finanzas

- Mercadotecnia y Análisis

- Administración

- Emprendimiento

- Recursos Humanos

Escuela de Humanidades y Educación

- Medios y Cultura Digital

- Estudios Humanísticos

- Idiomas

Escuela de Ingeniería y Ciencias

- Física

- Ingeniería Industrial y de Sistemas

- Ingeniería Mecánica

- Ciencias Computacionales

- Mecatrónica y Automatización

- Bioingeniería

- Sustentabilidad

- Tecnologías Civiles

Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud

- Biociencias

- Psicología Clínica

- Nutrición

- Bienestar Integral

- Medicina

- Odontología

Paso 1—Answer the following questions in English.

- The section titled “Diferencia Tec” explains what Tec’s mission is. How is this mission similar to or different from your university’s?

- Why would an international student want to study in Tec?

- Are school rankings important to you? Which one of the rankings mentioned in the article do you find most impressive?

Paso 2—Answer the following questions in Spanish.

- Escoge las cinco razones más importantes de estudiar en el Tec de Monterrey de la sección titulada “10 razones para estudiar en el Tec de Monterrey.”

- ¿Qué facultad y programa del Tec te interesa más? ¿Por qué?

Paso 3—Watch the following video to see more about how Tec markets itself to students:

Then write three things you notice that you think your university could incorporate.

1.

2.

3.

Actividad presentacional 5.18. Un folleto

Now that you’ve read and watched some promotional materials for Tec de Monterrey, you will work with a group to create a brochure to attract a specific type of (Spanish-speaking) student to your university. Follow the prompts below:

- Pick a type of student: athlete, artistic-minded, first-generation, leader, religious, and so on.

- Go to your university website and find information that will specifically appeal to this type of student: clubs, organizations, types of classes, extracurricular activities, and so on.

- Design a brochure in Spanish that includes:

-

- A list of classes that might be interesting to this type of student.

- A description of what professors are like.

- Extracurricular activities or programs that might appeal to your type of student.

- Tools or programs available to help the student succeed.

V. Video entrevistas

Actividad interpretativa 5.19. Mis clases

Watch and listen to the videos and then answer the following questions in complete sentences.

- Lisa:

a. ¿Qué estudia Lisa?

b. ¿Cuántas clases toma Lisa, y cuáles son?

c. ¿Cuál es su clase favorita, y por qué?

d. ¿Cuál es su clase menos preferida?

e. ¿Qué más hace en la universidad?

f. ¿Qué les recomienda Lisa a otros estudiantes?

- Robin:

a. ¿Qué estudia Robin?

b. ¿Cuántas clases toma Robin, y cuáles son?

c. ¿Cuál es su clase favorita, y por qué?

d. ¿Qué les recomienda Robin a otros estudiantes?

Actividad interpersonal 5.20. Preguntas personales

Watch and listen to the questions from Mariangel and prepare a response to each one:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

VI. Gramática

5-A. El presente progesivo

The present progressive or continuous is a tense that is used to indicate that an action is taking place or is in progress at the moment of discourse. This is the same in English and in Spanish.

Examples:

Right now, I am writing a message.

Ahora, estoy escribiendo un mensaje.

In English, the present participle is formed by using a form of the verb to be and a present participle. The present participle is formed by adding -ing to the verb:

I am drinking water.

She is watching TV.

In Spanish, the present progressive is formed by using a form of the verb estar plus a present participle. In order to form the present participle, it is necessary to do the following:

- Drop the ending of the verb. This is the -ar, -er, or -ir located at the end of the verb.

- Add the following endings:

For -ar verbs: -ando

For -er and -ir verbs: -ando or -iendo

See the examples below:

| Form of the verb estar | Bailar |

| Estoy

Estás Estamos Están Estáis Están |

Bailando

Bailando Bailando Bailando Bailando Bailando |

| Form of the verb estar | Comer |

| Estoy

Estás Estamos Están Estáis Están |

Comiendo

Comiendo Comiendo Comiendo Comiendo Comiendo |

In both English and Spanish, the same present participle is used for all the forms. The form of estar in Spanish or of the verb to be in English determines who is doing the action.

Example:

Yo estoy jugando videojuegos.—I am playing video games.

Mi hermana está jugando a las cartas.—My sister is playing cards.

In Spanish, when the present participle of a verb has three vowels together, it has a spelling change in which the middle vowel changes to a y. This usually happens with -er and -ir verbs that have two vowels together.

Examples:

Leer: Leyendo (not leiendo)

Mi madre está leyendo un libro.

Creer: Creyendo (not creiendo)

No estoy creyendo nada de lo que dice.

Traer: Trayendo (not traiendo)

¿Quién está trayendo el café?

Actividad 5.21. Conjugaciones

Conjugate the verb for the given subject using the present progressive.

Modelo:

Leer

Yo __estoy leyendo__

Actividad 5.22. ¿Qué están haciendo?

Look at the images and indicate what each person is doing.

|

Modelo:

Ella está escuchando música |

|

Yo |

|

Mi madre |

|

Los estudiantes |

|

Los amigos |

|

Nosotros |

Actividad 5.23. ¿Qué están haciendo y dónde lo hacen?

Indicate what people are doing and where they are doing it.

|

Modelo: Los estudiantes están haciendo experimentos de química en el laboratorio. |

|

|

|

|

|

Actividad 5.24. ¿Qué están haciendo los famosos?

People like to know what their favorite famous people are doing. Follow the steps below and share with your partner what your famous person is doing.

Go to your favorite famous person’s social media account (Instagram, Facebook, etc.) and select two pictures in which the famous person appears. Describe each photo in writing using the present progressive and be ready to share the photo and your sentences with the class.

Modelo:

En una foto de Instagram, Shakira está montando en bicicleta con sus hijos.

5-B. Ser versus estar resumen

In previous chapters, you have learned that the verbs ser and estar both mean “to be” in English. However, they are used for different purposes. Below is a summary of the uses for each verb.

| Ser is used to: | |

| Identify, describe, or define | Es un libro

Es rojo y grande Es un medio para grabar información |

| Express intrinsic characteristics | Laura es alta y delgado |

| Indicate professions | Laura es una estudiante |

| Indicate nationalities | Laura es mexicana |

| Indicate possession or what something is made of | La mesa es de metal

Soy de Colombia |

| Express the place of an event | El concierto es en el parque |

| Express time and dates | Son las ocho de la mañana

Hoy es el quince de abril |

| Express impersonal information or with impersonal expressions | Es bueno hacer ejercicio

Es malo fumar |

| Estar is used to: | |

| Express location of people and things | La biblioteca está al lado del gimnasio |

| To talk about conditions and states | Estoy cansada hoy |

| To express an ongoing action with the present participle | Los estudiantes están escribiendo en sus cuadernos |

Actividad 5.25. ¿Ser o estar?

Fill in the blanks with the correct form of ser or estar.

Actividad presentacional 5.26. Mi evento favorito en la universidad

Use ser and estar to write an email to a friend or family member describing your favorite event on campus. Pretend the event is currently taking place as you write the email. Be sure to include the following:

- What the event is.

- Where it takes place.

- What time it takes place.

- How people feel when they are there.

- What they are doing while there. (Use the present progressive.)

Modelo:

Mi evento favorito en la universidad es el primer partido de fútbol americano. Los estudiantes están muy emocionados…

5-C. Pronombres de complemento indirecto

Several times in the tira, Pablo says, “Mi consejero me dice…” There are several possible translations of this phrase, which literally says “My advisor tells me.” Even though the word order is different between English and Spanish, don’t be fooled into thinking that the me means that I is the subject of the sentence. The me here functions as an indirect object pronoun, representing the noun that is indirectly receiving the action of the verb, tell.

Mi consejero me dice…

(Subject) (indirect object) (verb, conjugated to match the subject)

Indirect objects are people, places, and things that receive or are affected indirectly by the action of a verb. You can find the indirect object of a verb by asking “To or for whom (or what)?” to find the indirect object of a sentence. To whom did the advisor tell the information? To Pablo—or in his case, “to me.” Indirect objects in Spanish are typically expressed through a pronoun—a more general word that takes the place of a specific noun. Whereas in English, we need to say “(to) me, (to) you, (to) him, (to) her, (to) us, and (to) them,” in Spanish, we can say “a mí, a tí, a él, a ella, a nosotros, a vosotros, a ustedes,” but we must include an indirect object pronoun—“me, te, lo, la, nos, os, los, las”—before the verb. Take, for example, the following sentences:

Mi amigo me habla.—My friend talks to me.

Ana te da un abrazo.—Ana gives you a hug.

Indirect object pronouns in Spanish can be tricky for native speakers of English because of two main differences:

- Indirect object pronouns can be hard to identify in English. They sometimes have a preposition (“My friend talks to me”) and sometimes do not (“Ana gives you a hug”). Sometimes the indirect object is simply implied, as in “My advisor says…” though clearly the advisor is saying the advice to someone.

- The placement of the indirect object pronoun is very different.

- In English, object pronouns are placed after the verb: “My friend talks to me,” “Ana gives you a hug.”

- In Spanish, the pronoun is placed before the conjugated verb rather than after it, as in English.

- In Spanish, the object pronoun can also be attached to the end of an infinitive, as in “¿Quieres decirme?” or “Más tarde va a gustarle.”

There are also a couple of other situations in which the pronoun can be attached to the end of a verb, but in order to begin to change the order of your thinking (to “My friend to me speaks” from “My friend speaks to me”), it’s a good idea to get in the habit of placing the pronoun before the conjugated verb. It can never go on its own after a conjugated verb, as in “Mi amiga habla me.”

Similar to English, however, there are unique pronouns for each person. Refer to the chart below for the indirect object pronouns in Spanish and their meaning in English.

| singular | plural | |||

| first person | me | (to) me | nos | (to) us |

| second person | te | (to) you | os | (to) y’all |

| third person | le | (to) him/her/you | les | (to) them / you all |

Indirect object pronouns are almost always used if there is someone or something to or for whom the action takes place. It can be helpful to mentally pair certain verbs with indirect object pronouns, since they tend to go together. Two verbs that you have already learned that often take an indirect object pronoun are decir and dar.

When someone is telling someone something or giving something to someone, in Spanish, you should include an indirect object pronoun. This is different from American English, where we might omit the indirect object altogether. For example, in the phrase “Mi consejero me dice,” we might just as often say “My advisor says.” In Spanish, though, we do want to include the indirect object pronoun if someone is being directly spoken to, is receiving something, or is generally indirectly affected by the action of the verb. Another example is gustar and verbs like it.

Actividad 5.27. Traducciones

Translate the following sentences into English.

Modelo:

Mañana es el cumpleaños de mi mamá. Le compro un regalo (gift).

Tomorrow is my mom’s birthday. I am buying her a gift.

- Mis amigos me dicen que hay una fiesta mañana.

- El profesor nos habla.

- ¿Quién te ayuda con la tarea?

- Mi amigo está ayudándome.

Actividad 5.28. ¿A quién?

Fill in the blank with an indirect object pronoun to rewrite the sentence.

Modelo:

Compro un regalo para mi mamá.

Le compro un regalo.

Actividad 5.29. Translations

Translate the following sentences into Spanish. Be sure to use an indirect object pronoun.

Modelo:

Will you bring me a book?

¿Me traes un libro?

- My mom tells me important things.

- I will give her the calculator.

- She brings them a notebook.

- I tell you the truth (la verdad).

- She gives him the notes.

5-D. Verbos como gustar

Actividad 5.30. Verbos como gustar

We have already seen the phrases me gusta and te gusta to talk about preferences regarding activities. While we tend to translate me gusta as “I like,” it is important to note that this structure in Spanish is very different from the verb like in English. The main difference is that gustar and verbs like it take an indirect object pronoun and have a different subject than the person who likes or doesn’t like an activity. The best literal translation of the verb gustar is “to be pleasing to,” since that translation accounts for the fact that the thing or activity is actually the subject of the verb, and the person to whom the activity is pleasing is represented using a direct object pronoun.

When I say “Me gusta correr (en el parque),” I am actually saying “Running (in the park) is pleasing to me.” The subject of the verb gustar is the activity correr and not yo. This is always the case with gustar and similar verbs. Below is a chart with verbs like gustar that take indirect object pronouns. They are categorized according to whether they express more positive or more negative opinions. Note that you can also make the positive verbs negative by adding a no, as in “No me gusta correr.”

| Positive | Negative |

| Gustar (to like / to be pleasing to)

Encantar (to love / to be enchanting to) Fascinar (to be fascinating to) Interesar (to be interesting to) Importar (to be important to) |

Molestar (to be bothersome to)

Fastidiar (to be annoying to) Disgustar (to be displeasing to) Aburrir (to be boring to) |

Actividad 5.31. ¿Me, te o le?

Actividad 5.32. No me encantan

Choose the (a) most appropriate verb and (b) correct conjugation of the verb like gustar.

Modelo:

A mi amigo, le ________ la música. Toca en una banda y la escucha mucho.

a. interesa

b. interesan

c. molesta

d. molestan

Actividad 5.33. ¿Te gustan?

Write two sentences to describe how you feel about the following. The first should use a verb from the list and the second should explain why.

Modelo:

Los perros

Me encantan los perros. Son muy divertidos.

- El invierno

- La clase de matemáticas

- Correr

- La poesía

- Los libros históricos

Actividad interpretativa 5.34. La primera semana de clases

Watch and listen to the video in which Priscila (on the right), Álvaro (in the middle), and Tiffany (on the left) discuss the classes they are taking, which ones they like, and why:

Then write a description of what you hear Priscila and Tiffany say, using the present progressive and verbs like gustar. See the model based on what Álvaro says for an example.

Modelo:

Álvaro está tomando las clases de empresariales y empresas. Le gustan porque está estudiando empresas.

- Priscila:

- Tiffany:

Actividad interpretativa 5.35. Estoy nerviosa

Watch the video in which Deysi tells Robin about some challenges she is having in her class:

As you watch, pay attention to the words and phrases Deysi uses to express her problem and the words and phrases Robin uses to make recommendations. Make some notes in the chart below.

| Words/phrases that express the problem and how Deysi is feeling | Words/phrases that Robin uses to empathize and make recommendations |

Now, answer the following questions in complete sentences.

- ¿Cuál es el problema de Deysi?

- ¿Cómo le hace sentir?

- ¿Qué le recomienda Robin?

Actividad interpersonal 5.36. Resolviendo problemas

With a partner, assign roles of person A or person B. Then talk until you reach an agreement to the problem presented in each scenario.

- You are very busy this semester in school. You are an athlete and also president of the Spanish club. However, you are not doing well in your classes. You are not studying as much as you should and you are getting bad grades in math class. You don’t know (saber) what to do, so you decide to ask a friend who is taking more advanced classes for help. You prefer to study at night, since this is when you are free from extracurricular activities. Explain your situation to your friend and convince him or her to help you.

- You have a friend who asked for help studying for math. You don’t mind helping, but your friend has very limited time to study and prefers to do it at night. You usually call your family at night, which is when they are home. Ask your friend what he or she is doing during the day that prevents him or her from studying during this time and convince him or her to make time to study during the day.

- “¿Qué es el bachillerato en Chile?,” Educación en Chile, May 2, 2022, https://elplande2020.cl/que-es-el-bachillerato-en-chile/; “Tú preguntaste: ¿Cómo se llama el bachillerato en Costa Rica?,” Todo sobre educación, September 29, 2022, https://unate.org/instituciones-educativas/tu-preguntaste-como-se-llama-el-bachillerato-en-costa-rica.html. ↵

- “Tabla de conversión de calificaciones,” Universidad de Granada, Vicerrectorado de Relaciones Internacionales, May 13, 2010, https://internacional.ugr.es/pages/movilidad/tablaconversioncalificaciones/!. ↵