11 How Do Media and Interest Groups Influence State Government?

Chad J. Kinsella

Chapter Summary

Interest groups and media play an important role in state politics, even though their respective responsibilities seem at odds. Interest groups are increasingly prevalent in state government and influential in supporting legislation that reflects their interests, sometimes more so than the constituents’. Local journalism has struggled in the twenty-first century, but those who still report on state and local government provide an invaluable service to constituents who otherwise might be unaware. This chapter examines the role of these organizations in political participation at the state level and encourages students to consider how they can be advantageous and also challenging to democratic engagement.

Student Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Identify the function and role of outside institutions such as the media, interest groups, and other organizations in politics.

- Chart the historical trends and changes in the media, including the evolution from localized newspapers to more nationalized online platforms.

- Evaluate the role of media markets and the various responsibilities of political media.

- Analyze the free-rider problem and how interest groups effectively recruit members.

- Assess the differences between interest group influence and media impact in state government compared to federal government.

- Understand the importance of grassroots movements and organizations in state politics.

- Apply a critical lens to the effect of interest group and media bias in state politics.

Focus Questions

These questions illustrate the main concepts covered in the chapter and should help guide discussion as well as enable students to critically analyze and apply the material covered.

How is interest group influence different at the state level compared to the federal level?

Why do people choose to join interest groups? How do interest groups overcome the free-rider problem?

How has media consumption changed over time? What impact can this have on citizens’ knowledge, perceptions, and behavior?

What are the primary purposes of the media in a democratic system of government? How is that role being satisfied or unfulfilled in the current political culture?

Introduction

In 2010, Ohio Republicans won control of both the statehouse and governor’s office. Then-Governor John Kasich and the Ohio Republican legislative caucus made it a priority to pass legislation enshrining a “right-to-work” law, as did several other Midwestern states that elected Republican majorities in the wave of 2010. Right-to-work laws make union membership optional, even in workplaces that are unionized, and are seen as a way to weaken unions that are most often allied with the Democratic Party. Ohio passed such legislation into law in 2010 via SB 5. Ohio unions mobilized and were able to collect enough signatures to trigger a referendum, Issue 2, on the law in 2011. Union efforts on Issue 2 were successful, winning by a wide margin in 2011, repealing the right-to-work law. This was a major victory for Ohio unions, who organized under the banner of the group “We Are Ohio,” raising $30 million to best their opposition in spending by a 3 to 1 margin.[1]

Groups also play a key role in legislative sessions themselves. In 2023, the Indiana state legislative session was a resounding victory for school choice advocates. The state legislatures passed a near-universal expansion of the state school voucher program, enabling almost all children in Indiana to be eligible to attend the school of their choice and ensuring that millions of dollars go to charter schools as opposed to public schools in the years to come. The legislation was passed on the heels of an intense lobbying campaign by a group called Hoosiers for Quality Education that saw them spend $433,754 on lobbying during the sessions and hundreds of thousands more on a marketing campaign supporting charter schools. Overall, $20.7 million was spent on lobbying the Indiana General Assembly in 2023, and an array of groups employed hundreds of lobbyists.[2]

These stories highlight instances where interest groups are involved in politics and affect policy in state government. Interest groups are organized groups of people who participate in the political process and try to affect politics and/or policy in such a way as to benefit themselves or their constituencies. Second only to political parties, interest groups are a major player in state politics and policymaking across all fifty states. They typically can call upon a large number of members, have offices in and around state capitols, and have access to significant amounts of money that are employed to influence politics and elections throughout the state and policy during legislative sessions. As the stories point out, they can be quite successful in their endeavors.

The number of interest groups has increased in the states over time,[3] and with that has come an increase in memberships, fundraising and spending on campaigns, and general presence in state politics just as in national politics. Depending on the state, certain interest groups are major players in state politics. In some states with weaker political party infrastructures, interest groups fill the void by providing funds, recruiting candidates, and offering guidance on policymaking.

What Are the Different Types of Interest Groups?

There are a variety of interest groups active in each state that vary in size, activity, and influence. In many cases, the legislation proposed will dictate how active interest groups are. Certain policy and spending initiatives will attract the attention of groups, with some organizing to oppose the legislature and others organizing to support it, depending on how the proposals are written and, more often today, the partisan makeup of the state legislature and who wrote the legislation. Several groups have to be active every session, as their issues are at the forefront of legislative business. If you attend a state university, your university employs at least one if not a team of lobbyists who constantly monitor legislation and budgets. Ultimately, if you can either visit or be an intern at a state legislature during a session, you will see a variety of interest groups.

Overall, the largest line items of every state’s budget are K–12 education and Medicaid, both encompassing a large number of groups who have varying interests in the activities and funds spent on them. Furthermore, states regulate economic activity, including beer and alcohol sales, insurance, professional licensing, natural resources, taxes, and several others. Given the breadth of involvement in several domains and the large amount of money at stake, groups of various types, backgrounds, and goals feel it is in their best interest (or in some cases, their survival is at stake) to influence state government.

One of the oldest and most prominent types of interest groups are those that represent individual businesses or a collective of businesses such as the state Chamber of Commerce. Depending on which state you live in, there may be several prominent businesses that are headquartered there or have significant interests or presence in the state. For instance, Walmart is the largest business in Arkansas, whereas Nike is the largest in Oregon, and General Electric is the largest in Massachusetts. Businesses sometimes have a direct interest in policy considered by the state legislature or the budget. Sometimes businesses benefit from tax cuts or portions of the tax code for employing citizens within the state or may have or wish to have direct business with the state. There are instances when businesses are indirectly affected by state policy, such as more recent policies surrounding the LGBTQ community, because businesses want to be able to hire the best and brightest, with potential employees feeling welcome. Also, transportation spending is important to businesses so that products can move easily to and from facilities.

Another one of the oldest and most well-known groups is unions. Unions represent organized labor in both the private and public sectors. The Service Employees International Union is active in many states and is a union you may belong to if you work in the service industry, such as in restaurants, while in college. Teachers are represented by several groups but most prominently by state affiliates of the National Education Association, who actively work to increase pay, rights, and the general well-being of public school teachers. Even some of your professors are represented by the American Association of University Professors. These groups all work for workers’ rights and often together to forward or stop legislation that threatens them all, such as right-to-work legislation. Unions will often work proactively to stop antilabor legislation while also supporting prolabor legislation.

Professional organizations are another type of interest group that is active in state government. These groups represent different professional organizations and industries, such as accountants, beer and liquor vendors, home builders, physicians, farmers (including specific types of farmers, like corn, soybean, sugar, etc.) car dealerships, and so on. Unlike unions, which bargain and sign contracts on behalf of their members, professional associations represent particular industries or fields and may be more active at times when policy is being considered that could affect the constituency they represent.

States also have interest groups that are ideological in nature and represent a particular side of a single issue. Given the ideological nationalization of partisanship that has occurred at the state level,[4] several ideological groups that are visible at the national level have state affiliates or state offices. In several cases, ideological groups form as part of a broader coalition to push a particular issue or, if a state has direct democracy, to organize to support or oppose the issue on the ballot.

Finally, there are public-sector interest groups. These represent multiple public-sector entities and can include state and private universities, municipal and county associations, school board associations, and a host of other public entities within a state. These interest groups can represent both local elected officials and public employees.

Why Join an Interest Group?

There are several motivations for people to join interest groups. First, people join interest groups for information purposes. Interest groups are active and informed about state laws and changes that are made. They can offer conferences, newsletters, and training to inform their members about state laws and policies that pertain to their particular interest group members and keep them aware of changes that affect them. City and county associations across the country have annual conferences to inform members of state budgets and policies that affect these local governments.

An obvious advantage of joining many interest groups is the material benefits that come from joining. Material benefits come in many forms. Union members join because these groups provide job security and negotiate their contracts and, in doing so, generally try to get increased pay and benefits. State teachers’ associations have done this for years and, across many states, have large numbers of members because they actively attempt to improve teacher pay and benefits. Several professional associations and businesses actively seek state contracts for a variety of services and may live or die by their ability to obtain contracts and keep them in the state budget.

Finally, people join interest groups because of solidarity with the purpose of the group. Many interest groups have members who believe in the cause and mission of the group. This is especially true of the many ideological and single-issue groups that exist in the states either as state affiliates of a national group or as state-level groups. In different states at different times, the issue of medical malpractice reform has come up for debate in state legislatures. Interest groups that represented patient rights and lawyers would compete with groups representing hospitals and doctors for legislatures’ attention. It is the goal of these interest groups to either encourage or stop legislation passing medical malpractice reform that would put limits on payments in lawsuits dealing with medical malpractice. More recently, state affiliates of the National Rifle Association have competed with antigun groups such as the Brady Campaign regarding gun rights that are still hotly debated in state capitols across the country.[5] These groups will donate money to supportive legislators; plan protests; conduct email, phone call, and letter-writing campaigns; and make endorsements in primary and general election races to mobilize their constituents to support and vote for like-minded legislators.

How Do Interest Groups Influence?

Interest groups are heavily involved in state politics and policymaking. Every interest group is interested in ensuring the best outcomes for their members and employs a variety of tactics to influence. Overall, interest groups use four main tactics to influence. These include (1) lobbying; (2) grassroots lobbying; (3) making political contributions to friendly state policymakers, especially through political action committees (PACs); and (4) conducting public relations campaigns to successfully institutionalize or block policy.

Lobbyists are representatives hired by interest groups to influence the decisions of government officials. Interest groups will sometimes hire their own in-house lobbyists or contract with a lobbying, law, or public relations firm to represent them. Several firms are located near the state capitol with the expressed intention of having a regular and visible presence for lawmakers. Law firms around the state capitol will often have a government relations department as part of their firm that employs lobbyists. In state capitols across the country, hundreds of lobbyists are employed, and groups spend hundreds of millions of dollars to influence state officials.

|

State |

Year |

Registered Lobbyists |

Total Spending |

|

AK |

2022 |

95 |

$21,287,317.79 |

|

CA |

2022 |

1802 |

$445,524,124.55 |

|

CO |

2022 |

367 |

$68,518,640.82 |

|

CT |

2022 |

769 |

$110,899,868.51 |

|

FL |

2022 |

1855 |

$276,009,000.00 |

|

IA |

2022 |

656 |

$21,635,921.06 |

|

KY |

2022 |

685 |

$24,383,228.38 |

|

MA |

2022 |

1401 |

$111,822,713.83 |

|

ME |

2022 |

185 |

$3,307,168.41 |

|

MI |

2022 |

1371 |

$49,934,738.39 |

|

NE |

2022 |

443 |

$22,232,038.47 |

|

NJ |

2022 |

986 |

$95,076,033.71 |

|

NY |

2022 |

1329 |

$330,542,990.00 |

|

OR |

2022 |

937 |

$45,516,102.64 |

|

SC |

2022 |

411 |

$26,058,732.61 |

|

TX |

2022 |

1607 |

$229,328,494.05 |

|

VT |

2022 |

642 |

$10,113,300.16 |

|

WA |

2022 |

1074 |

$79,290,399.53 |

|

WI |

2022 |

694 |

$31,917,844.00 |

Table 11.1 shows several state lobbying records for 2021 and 2022. The number of lobbyists and the amount spent varies significantly by state. Large states such as California, Florida, Texas, and New York have over a thousand lobbyists employed, with spending that goes into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Smaller states such as Alaska, Maine, Kentucky, and Connecticut reveal significant diversity, with variation in the number of lobbyists (ranging from less than a hundred to several hundred lobbyists) and the amount of money spent (ranging from a few million dollars in Maine to states spending tens of millions of dollars). The number of lobbyists in a state is also affected by the political culture of the state (moralistic, individualistic, or traditionalistic), whether the legislator is full or part time, and even how states define what a lobbyist is—some states have expansive definitions requiring large-scale registration, while others have restrictive definitions requiring fewer people to register as lobbyists.

Lobbyists play a critical role in the policymaking process. Their number-one job is to inform legislators and others involved in policymaking about the interest(s) they represent. Much of lobbyists’ time is spent before and during sessions getting meetings with legislators, ranging from conversations in their offices to group-financed dinners and social gatherings in and around the state capitol. Many legislators are elected and have a background in or passion for certain policies, but most are not well versed in all areas taken up by state government. This provides lobbyists an opportunity to fill this void by providing information to legislators on the policy preferences of the group they represent. For instance, if a legislator is a retired teacher and ran based on their knowledge and passion for education, they may not know much about banking, medical malpractice, or a range of other critical issues the state legislature will consider. Lobbyists help provide critical information to state legislators, including personal narratives, statistics, and data to help convey their main points. Lobbyists must be experts in the areas they represent.

Research on core lobbyists’ activities in several states found that their successful tactics include the following:

- meeting personally with state legislators;

- meeting personally with legislative staffers;

- entering into coalitions with other interest groups;

- helping draft legislation;

- meeting personally with members of executive agencies;

- testifying at legislative committee hearings;

- meeting with members of the governor’s staff;

- talking with members of the media;

- organizing letter, email, and telephone campaigns to state legislators;

- providing written testimony to legislative committees;

- providing written comments on proposed rules and regulations; and

- assisting with the drafting of regulations, rules, and guidelines.[6]

As this list shows, there are a host of activities in which lobbyists engage. With the high number of lobbyists employed in state government across the country, it is clear that interest groups feel a need to have representation to safeguard their interests in state government. Even other government entities such as cities and counties within the state hire lobbyists to represent their interests and ensure that state funds to their local governments are protected or increased.[7]

Given the number of lobbyists employed in states and the amount of money spent on lobbying activities, it is clear that lobbying is an effective tool and provides access to groups that are beyond the means of most individuals. Given the popular skepticism the public holds of the lobbying profession, states have enacted regulations for lobbyists to abide by.[8] One of the most important aspects of state regulations is simply defining lobbyists, and the definition can vary greatly on how inclusive or inclusive it is by state. Also, states regulate lobbyist activities, such as reporting gifts given to legislators of a certain value or restricting them completely so that lobbyists have to register themselves and their activities with the state.[9] States have also created independent ethics commissions[10],[11] and disclosure laws including limits on gifts,[12] which include a complete prohibition (except for trinkets and mementos of low monetary value) in Minnesota or, similarly, gift limits of $10 in Arizona. The purpose of these laws is to provide greater transparency and reduce the influence of lobbyists on state elected officials.[13],[14]

The result is that every state legislature includes registration requirements for lobbyists before they can start with lobbying activities. Registration costs range from zero to several hundred dollars, with some states waiving fees for government or public-sector lobbyists. Some states require those who hire lobbyists (referred to as principals) to register either instead of their lobbyists or along with them. The information that lobbyists must register varies significantly from state to state, as can each state’s definition of a lobbyist. Overall, states require a filer’s name, address, client, and subject matters in which they are experts. Some states require photo identification, disclosure of sublobbyists in their employ, pledges of honesty, and even compensation. States with ethics commissions that oversee lobbying may require even more detailed registration to give them more discretion in lobbying oversight.[15]

Despite the concerns of Americans around interest groups and their lobbyists, lobbying can be an important, socially responsible activity.[16] The main job of lobbyists is advocacy, and this is often carried out in ethical ways by lobbyists in a variety of fields.[17] A lobbyist’s work is often directed at crafting good public policies that benefit society,[18] although what groups and lobbyists consider good public policy depends greatly on their own opinions and judgment. Lobbyists work for many causes and organizations, including higher education institutions. They seek to advance the needs of their clients and to provide positive outcomes for the community.

The professional organizations of lobbyists themselves encourage ethical behavior and professionalism, including ethical standards.[19],[20] Lobbyists must be good stewards of public trust and leverage their skills for the benefit of the public good, and to accomplish this, they must be honest, transparent, and accountable.[21] Lobbyists who violate these tenets face a variety of formal and informal sanctions. Formal sanctions include fines and imprisonment, while informal sanctions can cost a lobbyist their job—once they lose the trust of legislators, it is difficult if not impossible to get it back. In a survey of Indiana lobbyists in 2022, the vast majority reported that they adhere to all ethical behavior and work,[22] with all lobbyists saying they maintain appropriate confidentiality and turn down inappropriate requests.

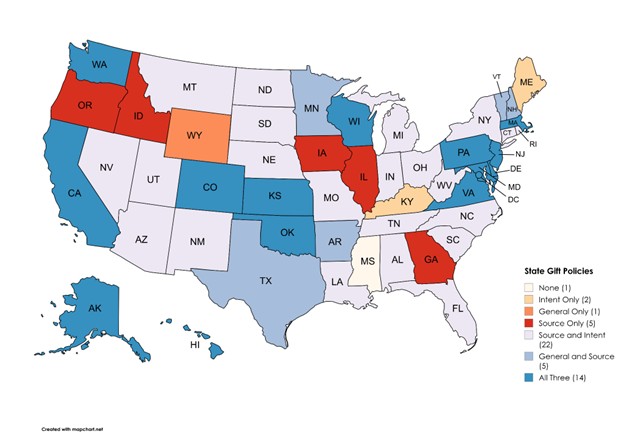

Beyond regulating lobbyists, states have enacted laws and regulations governing gifts to legislators and government officials. These stipulations also apply to all members of any kind of interest group. According to the National Association of Attorneys General, all states except Mississippi have enacted regulations and laws to dictate when elected or other government officials may and may not accept a gift. Overall, these regulations fall into three areas:

- General Restriction: This type of law or regulation prohibits a public official from receiving a gift regardless of whether the giver intends to influence the official. This type of prohibition is based on the idea that receiving anything of value without giving equal consideration in return may potentially create a sense of obligation in the recipient, thus ensuring the recipient of the gift does not feel indebted to the gift giver.

- Source-Based Restriction: This prohibits gifts given by interested parties such as lobbyists or a person who has business that lies within an official’s authority or jurisdiction. States vary on how they enforce these laws and regulations, with states like Colorado completely prohibiting gifts to officials, while other states, such as Pennsylvania, acknowledge that giving gifts such as shared meals and entertainment is part of the culture and limit and/or require disclosure as opposed to complete prohibition.

- Intent-Based Restriction: Gifts are restricted or allowed based on whether the giver intends to influence or could influence an official from otherwise being impartial in doing their duty or making decisions. Such gifts in this type of restriction are treated as bribery even if there is no specific quid pro quo (a favor for a favor) agreement (see Figure 11.1 for how states vary on gift restrictions).

Data Source: National Association of Attorneys General. “State Gift Laws.” 2024 / Map made by author.

Many states use a combination of gift restrictions as their official policy. Wisconsin, Washington, and Oklahoma use all three restrictions; Minnesota and Texas use a combination of general and source; Indiana and New York use source and intent; Wyoming uses only general; and Mississippi is the only state that uses none.[23] Research has shown that the results are clear. States that have increased formal lobbying regulations have seen a decline in the influence of interest groups in the legislative process, defined by a survey of state legislators on interest group influence on the legislative process.[24],[25] Furthermore, states that have strictly regulated lobbyists have seen an increase in state legislators’ consideration of their citizens’ opinions.[26]

Another major way in which interest groups are active in influencing policy is through direct involvement in the political process by donating to campaigns. Although the number of competitive state legislative races has steadily decreased for decades,[27] according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics, the amount of money spent on state legislative races has increased dramatically. For instance, in 2012, state legislative races raised and spent just over $1 billion, while in 2022, they raised and spent over $1.6 billion.[28] All fifty states have their sets of campaign finance laws that differ, sometimes dramatically, from federal standards enforced by the Federal Election Commission. Also, each state has an election administration agency and requires some form of disclosure. The goal of disclosure is to ensure transparency in elections, meaning that the public can obtain information on who is donating and how much.

States allow for different interest groups to contribute money to state legislative campaigns in several ways. One of these methods is through PACs. PACs are specialized organizations that are created for the sole purpose of raising and spending money on campaigns. Typically, PACs are affiliated with an interest group, and many of the affiliations are obvious in PAC names. Research on PAC donations has found that these donations do influence legislators, including a case where legislators in Florida were influenced when they voted on school vouchers after contributions from a teachers’ union PAC.[29] As with lobbyists, some states have enacted stricter campaign finance laws to limit outside influence.[30] Currently, thirteen states allow PACs to contribute unlimited amounts of campaign funds to state legislative candidates, while the remaining thirty-seven states allow for PACs to either contribute as much as individuals or set a different limit for them. States allow for PAC contributions but have limited how much they can give, including in Rhode Island and Florida ($1,000), or the proportion of the total amount of donations (50 percent), like Tennessee.

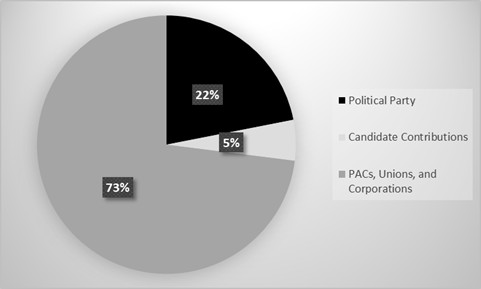

Unlike federal elections, many states allow corporations and unions to make direct contributions to state races. Currently, six states allow corporations to make unlimited contributions to state legislative candidates, and another twenty-two prohibit corporate donations to state legislative candidates. Nineteen states set corporate contribution limits as the same for individuals, and three other states set different amounts of campaign donation limits for corporations. Similarly, states also vary on union campaign contributions to state legislative candidates. Eight states allow unlimited union campaign contributions, and fourteen others prohibit union contributions. Another twenty states allow for union contributions at the same amount as individual donations, and five others allow unions to only contribute campaign funds to state legislative candidates equal to corporate donations or only through their PAC.[31] Of the nearly $600 million donated by nonindividuals in state legislative elections in 2022, $432 million was donated by PACs, corporations, and unions (see Figure 11.2). Ultimately, states with restrictions on donation amounts see fewer direct donations to legislators, while those with less restrictive policies rely on disclosure laws so citizens can see how much is being donated and by whom.

Data Source: OpenSecrets. Follow the Money / Chart by the author.

Table 11.2 shows three states (California, Minnesota, and Florida) with the top five contributing groups in 2022 along with their amounts. Donations all run into the millions of dollars, and depending on the state and its campaign finance laws, groups either donate directly, as in California, or find it better to donate to party or candidate committees who then make decisions on donations, such as in Minnesota and Florida.

|

California

|

Minnesota

|

Florida

|

|||

|

Spending Group |

Amount |

Spending Group |

Amount |

Spending Group |

Amount |

|

San Manuel Band of Mission Indians |

$105,672,007 |

Democratic Governors Association |

$7,650,165 |

Ron DeSantis Campaign Committee |

$94,429,753 |

|

Lyft Inc. |

$53,260,384 |

2022 Fund FKA 2018 Fund |

$7,525,000 |

Florida Republican Party |

$21,496,495 |

|

Davita Inc. |

$48,492,696 |

Democratic-Farmer-Labor Senate Caucus of Minnesota |

$7,476,714 |

Republican Governors Association |

$20,950,000 |

|

Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria |

$35,060,848 |

Education Minnesota |

$6,362,234 |

Friends of Charlie Crist |

$6,930,708 |

|

Fanduel Group |

$35,060,848 |

Democratic-Farmer-Labor House Caucus of Minnesota |

$4,668,476 |

Duke Energy |

$5,588,073 |

Another major method used by interest groups to lobby is through grassroots lobbying. Grassroots lobbying is the use of interest group members to contact elected officials in an attempt to sway them to support the issues championed by the interest group. Essentially, this is using the strength of numbers to sway policymakers and can be as or more effective than traditional lobbying efforts. Grassroots lobbying may employ a host of different tactics, such as letter/email writing, phone calls, meetings with elected officials, and protests.

In 2013, then-Governor Rick Perry called a special session to pass legislation restricting abortion rights in Texas. Groups like Planned Parenthood and NARAL Pro-Choice Texas rallied along with legislative Democrats to stop the bill. After Democrats in the senate fell short in their attempt to filibuster legislation until the deadline of the special session at midnight, protesters shouted and caused general chaos to bring all legislative activity to a halt until the midnight deadline. Although Perry was able to call another special session and pass the legislation, the delay illustrates what an effective grassroots lobbying campaign can do.[32] More recently, in response to restrictive gun laws passed by Illinois’s Democrat-dominated state legislature and signed into law by Democratic Governor J. B. Pritzker, the Illinois State Rifle Association protested in a march in Springfield in an attempt to have their voices heard.[33] Grassroots lobbying requires the mobilization of an interest group’s members and can be a powerful influencer in state capitols. Even a simple email campaign to legislators can influence legislative voting behavior.[34]

In many instances, particularly if an issue that is critical to a group comes to the forefront, groups will organize and employ every method possible to influence, including deploying commercials on television and social media. As states have adopted a host of different policies depending on which party controls state government,[35] certain interest groups have an outsized amount of influence depending on their closeness to the party in power. Overall, studies have found that there are twelve determinants of how much influence groups have in state government:

- how necessary a group’s services and resources are to state officials;

- whether a group’s lobbying efforts are primarily defensive (trying to stop policy) or offensive (trying to pass policy);

- the strength of a group’s opposition;

- the potential for a group to enter into a coalition;

- a group’s financial resources;

- the size and geographic distribution of a group’s membership;

- the political cohesiveness of a group’s membership;

- the skills in management, organization, and politics of a group’s leadership;

- political climate;

- lobbyist and policymaker relations;

- how legitimate a group’s demands are perceived by the public and policymakers; and

- the amount of autonomy a group has in political strategy making.[36]

What Is the Role of Media in State and Local Government?

In the early spring of 2018, after a brief meeting with his caucus, the Republican majority leader of the Iowa State Senate emerged and issued a letter just one sentence long: He was resigning. This tumultuous ending was the result of an investigation by a small political website in Des Moines that posted a video of the former majority leader meeting with a female lobbyist in a bar and the two kissing. Many in Iowa considered that such a relationship would have undue influence and rocked a legislature that had recently had a $1.75 million judgment against it for sexual harassment.[37]

In Rhode Island in the 2016 election, Moira Walsh defeated a Democratic incumbent in the primary and won an uncontested general election. The reform-minded Democrat was in for a shock almost as soon as she was sworn in. Shortly after taking office, then-Representative Walsh spoke to a radio host and talked about how surprised she was at the amount of drinking that took place on the legislative floor and how disappointed she was that votes could be taken on critical issues with those casting those votes “half in the bag,” a term used to describe being nearly drunk. Before ever being sworn in, she had discussed concerns over the rumors about the amount of drinking that went on during sessions. After this interview was reported widely in the media, leadership in the Rhode Island House reacted swiftly. The house majority leader told state media outlets that he had never witnessed anyone intoxicated on the floor while voting. Concerns about drinking during the session were not confined to Rhode Island, as during the same year, Missouri proposed a ban on drinking in the statehouse, Oklahoma had already banned alcohol from the capitol building, and California instituted free after-hours transportation for state legislators in 2015 after a rash of drunk driving arrests.[38] After losing her seat in the Democratic primary in 2020, Walsh stated that one of her greatest accomplishments was moving drinking off the floor and making it less acceptable.[39]

Perhaps one of the most powerful and important institutions in the states is the media that covers state government and politics. Indeed, one of the most critical parts of a functioning democracy is to have a free and fair press. Just like national news outlets keep us informed about governance and politics in Washington, DC, state governments have media outlets in their respective state capitols that discuss governance, politics, and policymaking in state government. Like the national media, state media functions as a watchdog, is an outlet for politicians and interest groups to take their case to citizens, and informs citizens about state government and politics. Unlike the national media and Congress, though, lawmakers at the state level are far more accessible and very interested in the press attention.

There are several forms of media. Traditionally, media is defined as being either print, radio, or television. The advent of the internet and social media has drastically changed how some of these traditional media outlets do business, as many, if not all of them, now use websites and social media as mediums to reach their audience. Almost all newspapers use websites and post articles, with some regional and local papers going exclusively online. The number of statehouse reporters working for digital-only outlets accounts for the fast-growing areas covering state government.[40] Television uses clips of their broadcast and posts those videos online as well as posting digital content that can be read. Radio also posts articles online and utilizes podcasts to reach a broader market. Almost all reporters, regardless of what outlet employs them, use social media such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter/X to post content and engage with their audience.

Overall, media is expected to cover a geographic area called a media market. Traditionally, there are 210 media market areas throughout the United States that vary considerably in size, with New York being the largest media market and Glendive in eastern Montana being the smallest. Part of the job of the media in each media market is to provide local news to the areas encompassed in their geographic setting, which can be a difficult job considering the size and diversity of some of the markets. For example, the Cincinnati media market encompasses portions of three different states: Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky.

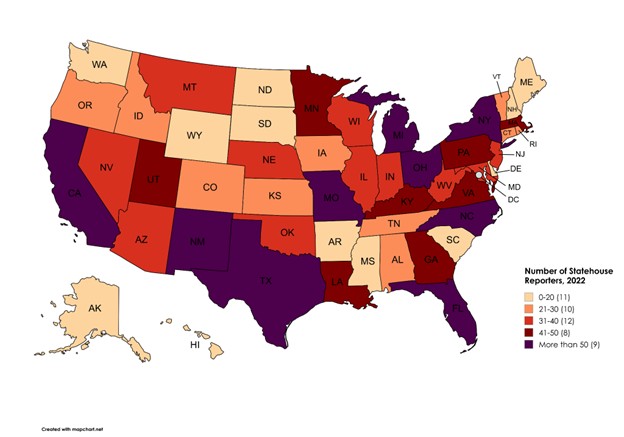

Despite the lofty goals and expectations of media covering state government, there are negative trends with state news outlets. Research shows that between 2003 and 2009, there were a third fewer full-time reporters devoted to covering state government and politics across the country, and by 2009, half of states had five or fewer full-time reporters.[41] In 2014, there were 1,592 statehouse reporters covering state politics; however, by 2022, there were 1,724 statehouse reporters (see Figure 11.3 for the number of reporters per state). Despite the increase in reporters, the number of full-time reporters had decreased between 2014 and 2022, with many statehouse reporters either working part time or even being student interns.[42] Not only are there problems with the number of reporters, but media consolidation is an ongoing trend in which larger companies have purchased smaller ones. Currently, 75 percent of all print newspapers are owned by one of three major media conglomerates. This has led to the need for these companies to shift coverage that can be distributed in multiple markets like national news instead of market-specific state and local news. The result is less coverage of state and local news, less ideological diversity in coverage, and a decrease in viewership.[43]

Data Source: Pew Research Center. “U.S. Statehouse Reporters by State.” 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/feature/u-s-statehouse-reporters-by-state/. Map made by author.

Research argues that this decrease in state coverage has allowed state legislators to become more extreme than their districts due to the lack of media accountability.[44] Other research findings show constituents cannot recall the name of their member of Congress, but they usually can recognize their name.[45] The success rate for recognizing state legislators cannot be much better, as there is little media coverage of them.[46] State legislators are not the only people who are unknowns, as survey data from polling in Indiana in 2022 and 2023 found that nearly a third of respondents replied with “don’t know / not sure” when asked to approve or disapprove of Governor Eric Holcomb’s job as governor. Similar surveys in different states encounter the same problem (if they offer a “don’t know” option). Overall, as the media covering state government and politics has waned, so has knowledge about them.

Local news continues to see a long-term trend of diminishing resources dedicated to local politics, which, like state news, leads to a lack of accountability for local elected officials.[47] Also problematic is that the number of people who pay attention to local news continues to decrease, with only 15 percent of Americans saying they have paid attention to local news in the last year. Like national and state media, a growing number of people prefer to get their local news on websites or social media as opposed to television, print, or radio. Despite all the setbacks for local news, Americans still see value in local news and journalists, viewing them as a crucial part of the well-being of their communities.[48]

How Is the Media Regulated?

The US Constitution provides broad protections in the First Amendment for freedom of the press, but it is important to realize that those constitutional protections are not absolute. All media outlets are forbidden from broadcasting or printing defamatory statements, known as libel and slander, nor can the media publish classified material. The federal government has also created the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The FCC has created and enforced several rules that apply to radio and broadcast media, including the following:

- The Equal Time Rule: This rule requires broadcasters to provide equal time to all candidates for the same political office.

- The Right of Rebuttal: This rule requires broadcasters to offer the opportunity for political candidates to respond to criticism. Ultimately, if a station airs an attack on a candidate, then the candidate must be given a chance to respond. It is important to note that this does not include negative advertising, only criticism by the station itself.

- Indecency Regulations: This rule limits language considered profane and obscene visual content between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.—hours when children are likely to be watching or listening.

Currently, digital media has significantly less regulation, although there are calls and even attempts by states to change this. After the 2016 presidential campaign, Congress had hearings regarding interference by foreign actors who posted “fake news” on social media outlets such as Facebook to interfere with the American electoral process. More recently, states have attempted to regulate social media, with thirty-four state legislatures introducing various proposals. To date, three states have passed laws regulating social media. Texas and Florida passed laws banning the censorship of users’ viewpoints or the removal of political candidates from their platforms. New York passed a law requiring social media platforms to report and respond to hate speech, including fines for companies that do not comply. All three laws are currently being challenged in the courts.[49]

The media and individuals also have rights regarding access to government information. Sunshine laws are laws intended to help with government transparency by making most government documents and records available to the public and are governed by the Freedom of Information Act of 1967, which affords citizens and the media the right to request information from state and local governments. Furthermore, sunshine laws require government meetings, votes, and deliberations to be open and announced with sufficient notice, including the time and place, and the location to be accessible to the public and media. These laws are intended to decrease corruption and increase public trust in government. Despite the intent of sunshine laws, state law varies significantly on what can be requested, the time frame in which one can expect a response, and even who can make the request.

How Does Media Influence?

Despite the decrease in the number of people covering state politics and government, state news, like national news, still plays a critical role in influencing politics. One of the key functions of the media, offline and online, is agenda setting. Agenda setting is the process by which the media reports some issues and events while ignoring others, ultimately telling the public what is important. Politicians try and occasionally succeed at trying to put issues or events that are important to them at the head of the agenda. Likewise, state and local officials would sometimes prefer to slip things through without any notice and prefer less or no media attention.

Another way in which the media has traditionally affected politics is through framing. Framing is the ability of the media to influence how events, issues, and actions are interpreted through the use of certain videos, pictures, or phrases or even the inclusion or exclusion of information. An example of this is how crime in urban areas is covered, with some outlets sharing stories of violent crimes while omitting signaling that violent crime is down overall.

Priming is when the media calls attention to some issues and not others when evaluating public officials, issues, or events and includes setting up background information to provide context but perhaps also influence opinions with subsequent information. Priming and framing differ from agenda setting by essentially acting as filters by which news is evaluated. An example of this across all fifty states was how different governors responded to COVID in 2020. During that period of national crisis, all governors’ leadership abilities were judged by the actions they did and did not take regarding their COVID response.

Despite the decreasing number of reporters covering state government and politics, they still play an incredibly important role. As the stories presented illustrate, the media plays the critical role of a watchdog, making the public aware of wrongs, and usually, that coverage leads to policy change. State media informs. Again, because of the nationalization of media and politics, the public tends to forget or willingly ignore state politics despite state politics playing a more prevalent role in the daily lives of citizens than the federal government.

Conclusion

Interest groups play a critical role in state and local politics that is only eclipsed in importance by the parties themselves. There are many reasons why people join interest groups, and they represent diverse groups of people. Interest groups raise and spend large amounts of money and use those funds to lobby state legislatures and, through PACs, monetarily support sympathetic elected officials. States vary significantly on the regulation of money spent on campaigns by interest groups and even gifts that can be given to state officials. Interest groups are also able to mobilize their members to influence state officials.

Media in state and local government and politics plays a critical role but is going through monumental changes. Traditional media outlets of television, print, and radio use the increasingly popular formats of the web and social media to continue to connect with the public. Despite the importance of state and local coverage, the resources devoted to this coverage have continued to diminish, with negative impacts on state and local politics. The media is, overall, given great protections by the US Constitution but is regulated by the FCC, and although social media and the internet have few regulations, states have filled and continue to fill this void. Finally, despite the trend of diminished state and local coverage, the media still influences the public by what stories they decide to cover and how they cover them.

Bibliography

Ahlquist, Steve. “Representative Moira Walsh: The Exit Interview.” UpriseRI, September 28, 2020. https://upriseri.com/2020-09-28-moira-walsh/.

Associated Press. “‘File Cabinets Full of Booze’: Legislator Criticizes State House Drinking Culture.” The Guardian, March 7, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/mar/08/voting-while-half-in-the-bag-legislator-says-colleagues-are-a-drunken-disgrace.

Batheja, Aman. “How Activists Yelled an Abortion Bill to Death.” The Texas Tribune, June 28, 2013. https://www.texastribune.org/2013/06/28/how-activists-yelled-abortion-bill-death/.

Berg, Kati Tusinski. “The Ethics of Lobbying: Testing an Ethical Framework for Advocacy in Public Relations.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 27, no. 2 (2012): 97–114.

Bergan, Daniel E. “Does Grassroots Lobbying Work? A Field Experiment Measuring the Effects of an Email Lobbying Campaign on Legislative Behavior.” American Politics Research 37, no. 2 (2009): 327–352.

Blanc, E. Red State Revolt: The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics. Verso, 2019.

Boettner, T. “Does West Virginia Invest Enough in Education? A Closer Look at the Data.” West Virginia Center on Budget & Policy, June 6, 2019. https://wvpolicy.org/does-west-virginia-invest-enough-in-education-a-closer-look-at-the-data/.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Union Members—2023.” 2023. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf.

Burnette, D. “What Is #RedforED? Behind the Hashtag That’s All the Rage in Teacher Strikes.” Education Week, 2018. https://www.edweek.org/education/what-is-redfored-behind-the-hashtag-thats-all-the-rage-in-teacher-strikes/2018/05.

Caughey, Devin, and Christopher Warshaw. Dynamic Democracy: Public Opinion, Elections, and Policymaking in the American States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Cigler, Allan J., Burdett A. Loomis, and Anthony J. Nownes. Interest Group Politics. Rowan & Littlefield, 2019.

Constant, Louay M. “When Money Matters: Campaign Contributions, Roll Call Votes, and School Choice in Florida.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 6, no. 2 (2006): 195–219.

Cooper, Christopher A. “Media Tactics in the State Legislature.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 2, no. 4 (2002): 353–371.

Enda, Jodi, Katerina Eva Matsa, and Jan Lauren Boyles. “America’s Shifting Statehouse Press.” Pew Research Center, July 10, 2014. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2014/07/10/americas-shifting-statehouse-press/.

Fields, Reginald. “Ohio Voters Overwhelmingly Reject Issue 2, Dealing a Blow to Gov. John Kasich.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 9, 2011. https://www.cleveland.com/politics/2011/11/ohio_voters_overwhelmingly_rej.html.

Flavin, Patrick. “Lobbying Regulations and Political Equality in the American States.” American Politics Research 43, no. 2 (2015): 304–326.

FollowtheMoney.org. “Contributions, State Legislative Races.” Accessed December 8, 2023. https://www.followthemoney.org/show-me?dt=1&c-exi=1&c-r-ot=S,H#[{1|gro=c-r-ot.

Givel, Michael S., and Andrew L. Spivak. “Bureaucratic Advocacy and Ethics: A State-Level Case of Public Agency Rulemaking and Tobacco Control Policy.” Public Integrity 14, no. 1 (2011): 5–18.

Goldstein, D. “West Virginia Teachers Walk Out (Again) and Score a Win in Hours.” The New York Times, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/us/teachers-strikes.html.

Goodall, Leonard E. When Colleges Lobby States: The Higher Education/State Government Connection. American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 1987.

Gorner, Jeremy. “Gun Rights Advocates Rally in Springfield, Deride the ‘Insanity’ of Weapons Ban Passed by Democrats.” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 2023. https://www.chicagotribune.com/politics/ct-illinois-gun-lobby-rally-20230330-5t4i4iojorbi3g2bxrhhw3rmzm-story.html.

Governmental Affairs Society of Indiana. “Governmental Affairs Society of Indiana Code of Ethics.” Accessed February 21, 2021. https://bit.ly/2RZ8v1s.

Gray, Virginia, and David Lowery. The Population Ecology of Interest Group Representation: Lobbying Communities in the American States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Hamilton, J. Brooke, and David Hoch. “Ethical Standards for Business Lobbying: Some Practical Suggestions.” Business Ethics Quarterly 7, no. 3 (1997): 117–129.

Hinckley, Barbara. “House Re-Elections and Senate Defeats: The Role of the Challenger.” British Journal of Political Science 10, no. 4 (1980): 441–460.

Hogan, Robert E. “State Campaign Finance Laws and Interest Group Electioneering Activities.” Journal of Politics 67, no. 3 (2005): 887–906.

Kern, Rebecca. “Push to Rein in Social Media Sweeps the States.” Politico, July 1, 2022. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/01/social-media-sweeps-the-states-00043229.

Kinsella, Chad, and Sam Snideman. “Ethics and State Level Lobbyists: Survey Results from Indiana.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, 2022.

Klarner, Carl. “Democracy in Decline: The Collapse of the Close Race in State Legislatures.” Ballotpedia, May 6, 2015. https://ballotpedia.org/Competitiveness_in_State_Legislative_Elections:_1972-2014.

Lange, Kaitlin. “Lobbyists Spent $20.7 Million During Session. Here’s Which Groups Spent the Most.” State Affairs, July 11, 2023. https://stateaffairs.com/indiana/politics/indiana-lobbyists-spent-most-education-health-care-energy/.

Leachman, M., and E. Figueroa. “K-12 School Funding Up in Most 2018 Teacher-Protest States, But Still Well Below Decade Ago.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/k-12-school-funding-up-in-most-2018-teacher-protest-states-but-still-well-below-decade-ago.

Martin, Gregory J., and Joshua McCrain. “Local News and National Politics.” American Political Science Review 113, no. 2 (2019): 372–384.

National Association of Attorneys General. “State Gift Laws.” Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.naag.org/state-gift-laws/.

National Association of State Lobbyists. “Code of Ethics.” Accessed February 23, 2021. https://statelobbyists.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NASL-Ethics-Statement-.pdf.

National Conference of State Legislatures. “Contribution Limits Overview.” Accessed December 6, 2016. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/campaign-contribution-limits-overview.

National Conference of State Legislators. “Lobbyist Registration Requirements.” Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.ncsl.org/ethics/lobbyist-registration-requirements.

Newmark, Adam J. “Measuring State Legislative Lobbying Regulation, 1990–2003.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 5, no. 2 (2005): 182–191.

Nownes, Anthony J., and Krissy Walker DeAlejandro. “Lobbying in the New Millennium: Evidence of Continuity and Change in Three States.” State Politics and Policy 9 (2009): 429–55.

Ozymy, Joshua. “Assessing the Impact of Legislative Lobbying Regulations on Interest Group Influence in US State Legislatures.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 10, no. 4 (2010): 397–420.

Ozymy, Joshua. “Keepin’ on the Sunny Side: Scandals, Organized Interests, and the Passage of Legislative Lobbying Laws in the American States.” American Politics Research 41, no. 1 (2013): 3–23.

Payson, Julia. When Cities Lobby: How Local Governments Compete for Power in State Politics. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Petroski, William, Brianne Pfannenstiel, and Jason Noble. “Bill Dix Resigns from Iowa Senate After Video with Lobbyist Is Posted.” Des Moines Register, March 12, 2018. https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/politics/2018/03/12/bill-dix-resigns-iowa-senate-kissing-lobbyist-video-bar/417333002/.

Pickerill, J. Mitchell, and Cynthia J. Bowling. “Polarized Parties, Politics, and Policies: Fragmented Federalism in 2013–2014.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 44, no. 3 (2014): 369–398.

Rogers, Steven. “Electoral Accountability for State Legislative Roll Calls and Ideological Representation.” American Political Science Review 111, no. 3 (2017): 555–571.

Rosenson, Beth A. “Against Their Apparent Self-Interest: The Authorization of Independent State Legislative Ethics Commissions, 1973–96.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 3, no. 1 (2003): 42–65.

Rosenson, Beth A. The Shadowlands of Conduct: Ethics and State Politics. Georgetown University Press, 2005.

Rosenthal, Alan. The Third House: Lobbyists and Lobbying in the States. CQ Press, 2000.

Shearer, Elisa, Katerina Eva Matsa, Michael Lipka, Kirsten Eddy, and Naomi Forman-Katz. “Americans’ Changing Relationship with Local News.” Pew Research Center, May 7, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2024/05/07/americans-changing-relationship-with-local-news/.

Shearer, Elisa, Katerina Eva Matsa, Amy Mitchell, Mark Jurkowitz, Kirsten Worden, and Naomi Forman-Katz. “Total Number of U.S. Statehouse Reporters Rises, but Fewer Are on the Beat Full Time.” Pew Research Center, April 5, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2022/04/05/total-number-of-u-s-statehouse-reporters-rises-but-fewer-are-on-the-beat-full-time/.

Strauss, V. “The Koch Network Says It Wants to Remake Public Education. That Means Destroying It, Says the Author of a New Book on the Billionaire Brothers.” The Washington Post, October 16, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/10/16/koch-network-says-it-wants-remake-public-education-that-means-destroying-it-says-author-new-book-billionaire-brothers/.

Strauss, V. “This Time, It Wasn’t About Pay: West Virginia Teachers Go on Strike over the Privatization of Public Education (and They Won’t Be the Last).” The Washington Post, February 19, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/02/20/this-time-it-wasnt-about-pay-west-virginia-teachers-go-strike-over-privatization-public-education-they-wont-be-last/.

Thomas, Clive S., Ronald J. Hrebenar, and Anthony J. Nownes. “Four Decades of Developments—the 1960s to the Present.” In The Book of the States, edited by Audrey S. Wall, 40. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments, 2008.

Walker, Jack, Jr. Mobilizing Interest Groups in America: Patrons, Professions, and Social Movements. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991.

- Fields, “Ohio Voters.” ↵

- Lange, “Lobbyists Spent .7 Million.” ↵

- Gray and Lowery, Population Ecology. ↵

- Caughey and Warshaw, Dynamic Democracy. ↵

- Walker, Mobilizing Interest Groups. ↵

- Nownes and DeAlejandro, “Lobbying,” 429–55. ↵

- Payson, When Cities Lobby. ↵

- Cigler, Loomis, and Nownes et al., Interest Group Politics. ↵

- Newmark, “Measuring State Legislative Lobbying,” 182–191. ↵

- Rosenson, “Against Their Apparent Self-Interest,” 42–65. ↵

- Rosenson, Shadowlands of Conduct. ↵

- Rosenthal, Third House. ↵

- Rosenthal, Third House. ↵

- Ozymy, “Assessing the Impact,” 397–420. ↵

- National Conference of State Legislators, “Lobbyist Registration Requirements.” ↵

- Hamilton and Hoch, “Ethical Standards,” 117–129. ↵

- Berg, “Ethics of Lobbying,” 97–114. ↵

- Givel and Spivak, “Bureaucratic Advocacy,” 5–18. ↵

- Governmental Affairs Society of Indiana, “Governmental Affairs Society.” ↵

- National Association of State Lobbyists, “Code of Ethics.” ↵

- Goodall, When Colleges Lobby States. ↵

- Kinsella and Snideman, “Ethics and State Level Lobbyists.” ↵

- National Association of Attorneys General, “State Gift Laws.” ↵

- Ozymy, “Assessing the Impact,” 397–420. ↵

- Ozymy, “Keepin’ on the Sunny Side,” 3–23. ↵

- Flavin, “Lobbying Regulations,” 304–326. ↵

- Klarner, “Democracy in Decline.” ↵

- FollowtheMoney.org, “Contributions, State Legislative Races.” ↵

- Constant, “When Money Matters,” 195–219. ↵

- Hogan, “State Campaign Finance,” 887–906. ↵

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Contribution Limits Overview.” ↵

- Batheja, “How Activists Yelled.” ↵

- Gorner, “Gun Rights Advocates.” ↵

- Bergan, “Does Grassroots Lobbying Work?,” 327–352. ↵

- Pickerill and Bowling, “Polarized Parties,” 369–398. ↵

- Thomas, Hrebenar, and Nownes et al., “Four Decades of Developments,” 40. ↵

- Petroski, Pfannenstiel, and Noble et al., “Bill Dix Resigns,” ↵

- Associated Press, “‘File Cabinets Full of Booze.’” ↵

- Ahlquist, “Representative Moira Walsh.” ↵

- Shearer et al., “Total Number of U.S. Statehouse Reporters.” ↵

- Enda, Matsa, and Boyles et al., “America’s Shifting Statehouse Press”; Rogers, “Electoral Accountability,” 555–571. ↵

- Shearer et al., “Total Number of U.S. Statehouse Reporters.” ↵

- Martin and McCrain, “Local News,” 372–384. ↵

- Rogers, “Electoral Accountability,” 555–571. ↵

- Hinckley, “House Re-Elections,” 441–460. ↵

- Cooper, “Media Tactics,” 353–371. ↵

- Martin and McCrain, “Local News,” 372–384. ↵

- Shearer et al., “Americans’ Changing Relationship.” ↵

- Kern, “Push to Rein in Social Media.” ↵