12 Local Government Structure and Organization

Laura Merrifield Wilson

Chapter Summary

Local governments range in size and scope from county governments, which are the administrative arms of the state and generally universal within a state, to city governments, which are granted power through a charter from the state and often have more authority than other incorporated municipalities. This chapter helps readers understand the differences among all types of local governments (county, city, township, special purpose, general function, etc.) in addition to the more nuanced variations of organization and structure (commission style, mayor-council, and council-manager). The benefits and disadvantages and unique features of each government are emphasized.

Student Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Identify the essential differences between county governments and city governments, including administrative tasks and authority.

- Explain the various structures of city governments and denote the benefits and disadvantages of each (commission, council-manager, and mayor-council).

- Describe at-large, district, and combination systems of local governments.

- Recognize the role of general-purpose local governments in comparison to the special-purpose local governments, including school districts and more specialized administrative bodies.

- Analyze the function of charters and the value of home rule in the relationship between local government and state governments.

- Apply residential mobility theory and push/pull factors to current local communities of growth and decline.

Focus Questions

These questions illustrate the main concepts covered in the chapter and should help guide discussion as well as enable students to critically analyze and apply the material covered.

What features make city governments unique from county governments?

How do the different structures of city government (commission, council-manager, and mayor-council) emphasize different values and preferences in city government?

Why are at-large systems a feature in some local governments for councils and legislative bodies but not at the state level?

How do charters and home rule play a role in municipal governance?

How can we apply residential mobility theory in our understanding of community growth and policy?

What Are the Powers and Divisions in Local Government?

Local government plays an essential role in the daily lives of Americans, providing valuable services such as sidewalks and road maintenance and trash collection and removal. Most Americans reside in cities or suburban or urban areas, and the impact of local government decisions is substantial. While it may lack the glamour and attention given to federal and even state governments, local government serves as the front line for essential functions. Sidewalks, parks, schools, police, sanitation—all of these are features of government with which we regularly interact. Public safety, public education, and infrastructure are necessary and expected in a modern society, and while other levels of government can influence these, they are largely the responsibility of local governments.

Yet it also often is seen as an afterthought compared to the state government. State government is far more visible, and its public officials are better known; the tasks it provides, while varying across the country, are generally monolithic and uniform across the state, meaning even as people may move across cities or counties, they are still bound by the same state laws and processes with which they are more likely to be familiar. Consider when many individuals interact with the state government: getting or renewing a driver’s license. Though they are located throughout the state in different municipalities, the state bureau of motor vehicles sets the policies (guided through legislative statutes), determines the costs, and enforces the regulations so the experience of procuring a license is universally the same regardless of where you live within the state.

Source: “Georgia counties map” by United States Census Bureau on Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

It is important to note that the states do treat local governments differently, though, as noted in Chapter 3. State constitutions include special provisions for local governments, noting what responsibilities and rights they may have, what title they may refer to themselves as, and what limitations to their powers may exist.[1] Some states allow significant local control, yielding some of the uniformity that could be held at the state level but enabling citizens to determine what they want to do uniquely in their local community that may differ from others.[2] This concept of home rule allows local governments more purview on policy and authority on issues and does not require the involvement or review of state government.[3]

Other states are more centralized in their organization and require changes in local municipalities to go through a state process. For some states, this may mean that the state legislature has substantial authority over aspects of local governing. In other states, it could go even further. Alabama’s State Constitution of 1901, used until 2023, mandated that any changes locally to government had to go through a statewide vote to make the proposed change within the state constitution.[4] This meant effectively that people in sixty-six counties would be voting on a decision made for a county in which they did not reside, nor were they necessarily impacted at all.

Because states have the sole authority to create, destroy, or alter units of local government, the relationship between state governments and local units is quite different from the relationship between federal and state governments. The power of local governments is highly dependent on state governments, but not exclusively so. Cities originate with an organization of residents in a particular community who then petition the state government for a charter. The charter provides authority and specifies details of power, including boundaries, elections, bureaucratic management and divisions, and the policy process as a whole. It can act like a constitution for local government management, but the authority that gives it power comes not solely from the people but also from the state government, which makes it ostensibly different in its function compared to constitutions.

Throughout this chapter, the balance of power between state and local government in local municipalities will be addressed, as both levels of government play a major role in the implementation of policies at a local level. We will also explore the differences between local governments, including general-purpose (county, city, and township) and special-purpose governments. In addition, we will cover the various types of organization for local government and also discuss residential mobility theory and factors that attract or repel prospective new residents to a community.

What Are City Charters, Home Rule, and Dillon’s Rule?

City governments are governed under charters. A charter is a legal document given to the city by the state government that outlines the powers and authority of the city.[5] It operates similarly to a constitution in that it serves as the guiding legal document for local government operations. A charter, however, is not as reciprocal as a state or federal constitution in neither its construction nor its implementation.

If residents of a state wish to change their state constitution (as discussed in Chapter 3), there are several mechanisms through which voters can make that change.[6] The constitution is responsive to voter change, and state constitutions regularly do change as the policies and preferences of voters do too.[7] If residents of a city want to amend their charter, they typically have to petition their state representatives and ask the state government for broader authority. This outlines an essential difference between the concept of constitutionalism, illustrated in our federal and state constitutions, and the power dynamic that appears in city charters.[8] Constitutions limit the power of government and uphold the power of the people; thus the people have the right, power, and authority to make changes to them. Charters do not come from the people, though, and instead are granted to the city from the state; thus it is the state who has the power to change them.

As noted in “What Are the Powers and Divisions in Local Governments?” earlier in this chapter, state governments have the power to create, alter, and destroy city governments. That language is intentionally strong and emphasizes the disproportionate power that a state has over the city through the charter. However, this power dynamic is not absolute, nor is it universal across all communities and states.

Some states empower city governments to play a greater role in policy and self-governance.[9] This concept is referred to as home rule in reference to the power vested in the city from the state government. States that enable home rule essentially allow city governments to be involved in matters not otherwise addressed by the state.[10] Whether a city pursues increased government involvement to respond to community needs or wants to legislate policy based on its own unique community experience, home rule allows the city to make decisions and act without the expressed permission of the state. One of the natural benefits of increased home rule is the autonomy and responsiveness it provides for local communities. Because communities have different needs, interests, and resources, home rule can exacerbate inequities, which may be undesirable.

Other states restrict the ability of cities and their involvement in policymaking. Dillon’s Rule describes the limited power that some states give to city governments to make decisions for themselves. In these situations, the state maintains the power to make changes, sometimes for or to the city without their consent. In Alabama, the State Constitution of 1901 stipulated that any change in local government had to be proposed and approved as an amendment to the state constitution (which explains, in part, the one-thousand-plus amendments made to the document before it was eventually replaced in 2022).[11] This creates a consistency across communities within a state, which can be advantageous in understanding the boundaries of power (as it is the same regardless of community). But preventing local input on decisions often feels restrictive and limiting, which can be frustrating to citizens seeking policy change.

What Are General-Purpose and Special-Purpose Governments?

Local governments can be organized in several different ways. In “What Are the Powers and Divisions in Local Government?” you learned that in some states, the name of a municipality reflects its population and special status. Later, in “How Do County, City, and Consolidated Governments Function?” you will see the difference in functions and responsibilities of different levels of local government. In addition to these, we can divide municipal governments into two other categories that aid in our understanding of the role they play in our lives.

Cities, counties, and consolidated governments are all examples of general-purpose governments. They serve a variety of functions under the umbrella of a single domain (i.e., the city of Miami) and operate within boundaries recognized by the state. Every resident in the United States is served in some capacity by these types of governments, and unlike special-purpose governments, these provide a range of services to constituents that might include police protection, infrastructure, health and safety, neighborhood services, parks, and libraries. Depending on the size of the municipality, several agencies or departments may exist to help execute the functions, but the policymaking process is still reserved for the county/city/consolidated government as a whole.

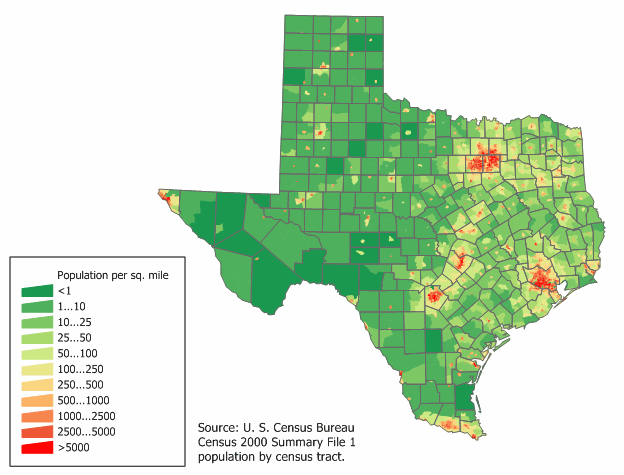

Source: “Texas population map” by JimIrwin on Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA.

Special-purpose governments focus on one particular function. They are oftentimes smaller than a county size and less visible to the general public despite their important work because of the niche specialization of their service.[12] Mosquito districts (popular in the Southern US, where the insects breed in high numbers and can carry disease) are created as boundaries to be treated with chemicals, minimizing mosquitos’ impact on the population. Water districts, sewer districts, and soil districts likewise provide essential functions but remain relatively unknown to most residents. Even more visible special-purpose governments, like fire districts, provide a limited function (addressing fires), involve relatively small boundaries, and are typically numbered throughout a city, so Fire House No. 14 serves a different district than the others.

By far the most visible and obviously impactful special-purpose government is the school district. School districts concentrate on K–12 education in a district within specific designated boundaries. The governing process is shared between the executive branch (known as a superintendent, usually appointed by the board of education) and the legislative branch (the school board, which is popularly elected).[13] In the most general sense, the school board is responsible for the creation of policy, then the superintendent implements the decisions.[14] The reality, however, is far more complicated given the magnitude of influence that state governments play in education policy. In circumstances where the state governments mandate school district compliance with a new policy, the role of the school board may be to address how the policy will be implemented, and the superintendent ultimately is responsible for that action.

How Do County, City, and Consolidated Governments Function?

As noted in “What Are General-Purpose and Special-Purpose Governments?” there are many different types of local governments, even those that serve multiple functions with broad scope. The differences between these general-purpose governments, though, are vast. To understand each type, we will describe county governments, city governments, and township governments. You will notice that while they all provide many different functions and thus are “general purpose,” they also serve different interests, particularly between the state and the local municipality.

County Governments

County governments are the primary substate governments that still serve the interests and functions of the state itself. Nearly all states utilize counties as a way to offer services at a more localized level that are not specific to the particular municipality but are needed and used across the state. They are sometimes described as the “administrative arm” of the state because their reach is wide enough to connect with residents, but they provide the same administrative functions across the state.[15]

County governments are responsible for county roads and other public works at a county-wide level and state certificates and licensing. Rather than drive to the state capital to apply for and receive a credential, the county serves as the “administrative arm” enabling residents to complete this task much closer to home.[16] Historically, this was necessary because of the tedious logistical challenges such a trip might entail; if you were a resident of Needles, California, in the far southeast part of the state, to simply venture to the state capital in Sacramento would require travel of 550 miles (hardly a short distance).[17] Travel time is not the only benefit of utilizing county governments to provide bureaucratic functions. Many of these functions are routine (such as getting a marriage license), and the congestion of having an influx of amorous couples constantly traveling to apply for state recognition of their matrimonious unions would be logistically inefficient.[18]

Licenses and certificates chronicling birth, marriage, divorce, and death are all offered by the county government.[19] They follow the same general guidelines across the state (so the mandatory waiting times for applying for and ultimately receiving a divorce do not vary from one county to the next).[20] In some cases, they may have slight variations where the state has allowed for some local government authority. For example, the state of Ohio has a dog license system, which compels owners to register their dogs with the state, creating a statewide network of registered canines and a robust system in case a lost pet is found.[21] The counties provide the actual dog licenses, and registration fees vary depending on the individual county, though the services and the function of the license are the same throughout the state.

Source: “Monroe LA – Ouachita Parish Court House” / Public Domain.

City Governments

City governments are granted charters from the state that outline their boundaries, responsibilities, and functions (as noted earlier in the chapter in “What Are City Charters, Home Rule, and Dillon’s Rule?”). Because cities exist separately, they have more specific functions relative to the amount of autonomy they are given by the state and their own community needs and priorities. Most cities provide some general services that one would expect in an organized municipality.[22] They offer police service, fire response, street maintenance, sewage and water, libraries and parks, and other services that would naturally be needed in an area with many people living closer together.

Larger cities may have greater needs depending on their population, so they offer more services accordingly. Large urban areas may have their own airports or convention centers that serve the neighboring communities and provide an attractive economic development option to bring tourism to the city. More rural areas do not necessarily need these services and will have a smaller population contributing to taxes simultaneously, so they are less likely to offer these to citizens.

Whereas counties serve the communities virtually identically across the state, cities can vary widely. Some states classify cities on the basis of population density within their boundaries and will grant them certain special privileges based on this; sometimes these classifications are even denoted in the name of the municipality itself, as some states reserve the term city for those areas with a certain population threshold, and those incorporated municipalities that are smaller are known instead as towns or villages. Other states make no such distinction.

Unified Governments

Some larger municipalities across the country have merged the services and offices of county and city governments to create a unified or consolidated government. In this case, rather than having a separate county government and a separate city government, the two are combined in several or all elements to create a larger city-county government that provides the functions of both.[23]

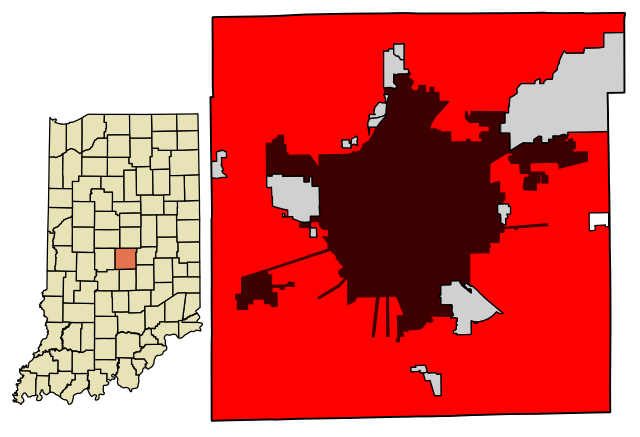

Consolidation was initially pursued because of the increasing problem of White flight during the 1950s and 1960s across the country.[24] After World War II, White residents began taking advantage of the Eisenhower interstate system and suburban housing opportunities and moved from city centers into the surrounding suburbs.[25] The taxable base from the city centers eroded, as the residents took their property tax, sales tax, and in some cases, income tax with them, all while the demands of the city and its services started to fail. Consolidating county and city government allowed the services to merge and the taxes to essentially be captured into a redistribution throughout the entire county rather than limited to much smaller city boundaries.[26] Another process, known as annexation, can extend a municipality’s boundaries but does not impact the duplication of efforts of city and county governments.

Source: “Rough Boundaries of pre-Univog Indianapolis” by IndianapolisWikipedian on Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA.

The problem of the duplication of efforts, familiar to all scholars of federalism, meant that taxpayers were funding both city and county governments with many redundant offices, practices, and functions. Consolidation eliminated an extra level of government by merging those services into the purview of one government rather than splitting it into two. An essential argument supporting consolidation is its efficiency: By eliminating the duplication of departments, services, and efforts that may overlap between county and city governments, the work is not redundant.[27] Opponents, however, argue that collapsing both county and city governments together means resources are spread more widely and may result in less equitable distribution when what only the city may need is instead expanded in offerings throughout the entire county.[28]

How Are County and City Governments Organized?

There are several different ways local, all-purpose governments can be organized. The selection is often based on community preference, but it is also not static.[29] As we will discuss, the preferences and what is most popular or preferred at the time have evolved and could reasonably continue. One thing that is worth noting in all types of organization is that the judicial branch is often not included in the same way that the boundaries and responsibilities of the executive branch and legislative branch are. This is because the state judicial system incorporates the local justice system, so the discussion here will focus on the differences in allocation of powers between the executive and legislative among the different types of local government.

For city governments, the three primary types of organization include commissions, the city council-manager system, and the mayor-council system. The commission form of local government organization folds the functions of both the executive branch (in implementing policy and managing bureaucracy) and the legislative branch (in creating policy) into one consolidated group of commissioners. They provide both functions at the local government and serve, in a sense, as equals.

Commissioners

The number of commissioners can vary, oftentimes in odd numbers, with as few as three members. The odd number is essential to avoid ties or gridlock in decision-making (important in government in general but most valuable when this one role provides two governmental functions). They are elected offices, and because there is a relatively small number of commissioners, they are typically organized in scattered elections so that the terms start and end at different times rather than electing all the commissioners in one election cycle. This protects institutional memory and prevents a full turnover, where all the incumbent commissioners choose not to run for reelection or are not ultimately reelected.[30]

The different policy/agency areas are divided among the commissioners, so rather than all commissioners being responsible for all things, one commissioner might be tasked with transportation and infrastructure while another is responsible for trash collection and park services. The division of services and tasks reveals one of the challenges of this style of government organization. Some responsibilities of local government are more exciting and intriguing to constituents than others, but all the work eventually has to get done. Voters may not think much about trash collection until theirs is missed and suddenly excess waste is piling up in the streets and angry phone calls illustrate their frustration with the missed service. Successfully collecting trash and being responsible for waste management are not going to get much attention when it is done well because that is the general expectation; residents quite frankly probably don’t notice until something goes wrong, and suddenly they care passionately. How the agencies, tasks, and responsibilities are delegated among commissioners can be very political and may feel unfair or uneven. But the consolidation of executive and legislative functions in the commission style of local government makes it necessary.

Another issue that arises in the commission style is the process of disagreement and recourse among the commissioners. This is sometimes referred to as a “three-headed monster” when you consider a commission of three people. Each may have different policy priorities or passion projects, different visions, and different plans on how to get there. Without an executive with some unilateral authority, these disagreements can lead to legislative gridlock, and the system offers few opportunities for resolution. Because of these challenges, the popularity of the commission form of local government has declined. After its origination in Galveston, Texas, at the beginning of the twentieth century, commissions became popular across the state and country.[31] Now the number of commissions is closer to 1 percent.[32]

Council-Manager System

Now the most popular form of local government is the council-manager system, which utilizes a strong city council and a subservient city manager. The city council serves as the legislative body, proposing and creating legislation such as city ordinances and playing the primary role in policies to be implemented by the chief executive (the city manager).[33] City councils vary in size and terms but tend to be as small as eight and as large as twenty people. In the “What Are the Types of Local Council Elections?” section, we will discuss the different ways these legislative seats are allocated and elected, such as districted systems, at-large systems, and combination systems. Regardless of how the elections are determined, the city council are all elected offices and thus responsive to the voters.

This is an important detail because it is one of the ways in which the legislative branch deviates from the executive in this system.[34] The city manager is not an elected post and instead is hired/appointed by the city council. Thus, they report to the council and not voters directly. City managers are often professionals with degrees in public administration or related fields who are responsible for managing the bureaucracy. They are not usually from the city in which they serve. This makes them very different from mayors, as we will discuss in the next subsection (“Mayor-Council System”), and this is an important distinction.[35]

One of the benefits of having a professional from outside the area is that they should be able to offer less biased opinions that are not as influenced by a personal history with the area. This allows them to focus more clearly on the task at hand, and their value lies in their background and expertise in city management. Of course, this also highlights the inverse challenge, which is that the city manager does not necessarily know the area as well and may not be able to take historical factors into play when employing their authority. This is at least in part why the bureaucratic power rests within the city manager and the legislative power is given to the city council (which would presumably have such memory and historical background knowledge).[36]

Mayor-Council System

The third type of local government organization is perhaps the most well known, even if it is not quite as popular as the council-manager system. The mayor-council system embodies both an elected executive with some unilateral and some shared powers and also an elected legislative body. The familiarity of this system of government stems from its prominence in larger US cities. The largest ten cities in the country (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, Philadelphia, San Antonio, San Diego, Dallas, and Jacksonville) all have mayors. These mayors sometimes become known as national figures, such as when a crisis occurs in their city that requires their leadership (such as Rudy Giuliani in New York City during 9/11) or because of their leadership and stature within the political party structure (like Rahm Emanuel from Chicago, who served as White House Chief of Staff under President Barack Obama before becoming mayor and then became the ambassador to Japan after leaving office).[37]

The mayor in this arrangement can hold significant power, and though they operate in the executive capacity and oversee the bureaucracy like a city manager, they are oftentimes more engaged in politics and more public facing.[38] This is largely due to the nature of the position. The mayor is publicly elected at large by the residents, making it a more expansive and expensive local campaign but also an office that is thus responsive to the voters. The politics of place can be influential in these elections, and successful mayors are often strategic in how they evaluate challenges and address solutions within their municipalities. Because this executive office is far closer to the public than the governor at the state level or the president at the federal level, the mayor has an opportunity to be highly visible in their work and close to the constituents and the community they serve. Depending on the size of the city, the office of the mayor may be a full-time post with a salary, or it could be a part-time position with a much smaller stipend that requires the occupant to be retired or have a flexible career to pursue local government leadership in addition to their full-time occupation.

The city council is an active part of this system of government too, providing legislative functions in a similar way to the council-manager arrangement. Here the council does not have a say in the election of the mayor as they do in the selection of the manager, which can create tension and conflict between the local branches of government. The mayor owes their job not to the council but rather to the voters, and depending on how the council is elected (districted vs. at-large elections), they may have different constituencies they are aiming to serve. A councillor from a small district on the edge of town could have one-sixteenth of the voters that the mayor has in a sixteen-person council, and those voters might be very different ideologically, culturally, and economically.

The councillors propose legislation and serve on various committees that represent large local policy areas. Sometimes, their committee service overlaps substantially or minimally and is informed by their professional work. Unlike the role of mayor, city council positions are not usually full time. Many of the meetings are held in the evening, both to accommodate the councillors who may have full-time jobs in addition to their role in local leadership and also because of an interest in transparency and accessibility for residents, who are welcome to attend open meetings and hear, see, and participate in the discussions. This is a unique feature of local government, particularly smaller city governments, where evening meetings are most prevalent relative to the state or federal levels. Congress could not only hold evening meetings; in addition to the fact that attendance would be only realistically feasible for local residents living close enough to Washington, DC, there is simply too much policy work and deliberation, making evening hours insufficient.

County Governments

County governments are often governed by elected officials like city governments but differ in scope and organization. When the city and county governments’ authority is separate and distinct, county governments can serve in executive, legislative, and limited judicial authority. The board of county government may be known as the county commission, board of supervisors, or county council. Depending on the size of the board, an elected county executive, known as the administrator, can provide daily direction. Other executive roles may include a county treasurer (responsible for funds), a county sheriff (responsible for law and order), and the county clerk (responsible for records).

Residential Mobility Theory

Americans move to new neighborhoods, new cities, new states, and sometimes even outside the country every year. In 2021, an estimated 12.8 percent of the US population moved in some form.[39] Most common were those who moved within different communities but still in the same county (6.7 percent), less common were those who moved to a different county within the state (3.3 percent), and just slightly fewer were those who moved to a new state (2.4 percent). Only 0.5 percent of Americans move outside the country annually.

These shifts in population can be attributed to several factors. First, people respond to economic and personal needs, situations that might require them to leave one area and relocate to another. Whether it is for a new job or a mitigating family circumstance, a move may be a necessary decision. Some moves are temporary, such as going out of state for college.

One way we can help understand the inertia involved in the decisions of where to move to and where to move from is to utilize residential mobility theory. This is an explanation of population shifts on the macro level that can specifically help explain why some communities are viewed as desirable and attract more residents while others struggle to maintain their population.[40] Residential mobility theory holds that pull factors are going to be those characteristics that draw people into a community and make that neighborhood appealing. The push factors are those qualities that will push residents out and make it less desirable for people to move in.[41] Pull factors include good schools, big houses, more space, and more amenities. Push factors involve crime (or the perception of it), congestion, traffic, and noise.

What Are the Types of Local Council Elections?

It is important to understand the structure and organization of local government to recognize the three different ways the council can be elected. The different election systems are influential in how campaigns are run and how candidates decide if and when to run. They are critical, however, in the actual organization element of the council. As noted in both “Council-Manager System” and “Mayor-Council System,” the way in which council seats are arranged can be impactful in the representation the city residents have on the council and potentially also the type of leadership the council provides. There are three different types of local council elections: districted, at-large, and combination systems.

District Elections

In what mirrors the legislative organization for state and federal governments, district elections divide out the boundaries of the community into equal parts proportionate to the number of seats in the council. These are allocated based on population, just as those in the state legislatures and Congress are. Single-member districts allow one member per district. The candidates eligible for office must all live within the boundaries of that district, and all the voters who may participate in the election also must reside within the district. In circumstances where multimember districts exist, multiple members from each district are selected.

These races are smaller and more focused, just as servicing the district is more concentrated on the particular communities included.[42] For councillors who serve in this capacity part time, this arrangement makes it easier to be a responsive and engaged representative. Conflict can arise in this type of system, though, as each councillor represents their own district and sometimes may observe tension in terms of what the district wishes to pursue or is in the best interest of the district in comparison to the city as a whole.

Most cities employ district-based organizations.

At-Large Elections

At-large elections encompass the entirety of the community with no smaller subsets. Just as the mayor is elected by the entire city, so too are at-large representatives. Because their constituency and “district” are the same, in this regard, mayors’ and councillors’ elections may look similar too, even though they still perform different functions of local government once in office. At-large elections mean that all candidates can run for one of the seats open, and all voters can select their preferences among all candidates. This can appear on the ballot for voters with instructions to select their top “X” number of candidates; the “X” number of candidates with the highest percentage of voters win the election.

At-large elections work well in smaller municipalities where there is not a great concern about equality and representation.[43] If the city is geographically constrained to a small space, the difference between having several winning candidates on one side of the road and only a few on the other is likely marginal in differences in representation. For larger cities, though, this approach can raise questions of equal representation.[44] Socioeconomic status is never equally distributed across a community, and candidates who can afford to run more sophisticated campaigns could be at a disproportionate advantage in being elected. One part of the city or neighborhood could be overrepresented while other areas do not have a person from their neighborhood in this position of power.

Combination Elections

The combination system includes some district seats and some at-large seats. Districts are drawn within the city, and candidates running in those elections may only run in the district in which they reside. At-large seats allow candidates to run citywide, and the first “X” many candidates voted for by voters across the city are elected. This system allows for the benefits of both options: There is diversity in terms of representation, and candidates who might live in a district with a strong incumbent can still run and be elected citywide. Because this system provides options for candidates, it gives flexibility in their decision-making about whether to run and how without facing the uphill battle of challenging an incumbent or having to wait until an open seat comes up.

Conclusion

Local government is often referred to as the nearest to the people it serves, and even though it captures fewer headlines and is not as well known as state and federal government, it plays a large role in our daily lives. Without county government, residents might have to clamor to the state capital any time a routine transaction with the state bureaucracy occurs, like renewing a driver’s license. Without city governments, large urban centers would miss out on providing unique services and features (like airports and convention centers) to cater to their specific needs. Special-purpose governments such as school districts provide an essential function in administering K–12 education at the local level that both serves and responds to our communities.

Local governments can be difficult to study because of the variety of types that the term local encompasses. As we discussed in this chapter, each different kind of local government serves a different purpose and scope. Because they are much smaller, local governments are close to the people, whether the municipality is organized by districts or representatives are selected in at-large races. The decisions made in our local communities play a vital role in the quality of life for residents and enable them to create a community that fits their needs and interests. Local governments may be less well known, but their influence on and responsiveness to residents underscore their value in our lives.

Bibliography

Abott, Carolyn, and Asya Magazinnik. “At-Large Elections and Minority Representation in Local Government.” American Journal of Political Science 64, no. 3 (2020): 717–733.

Barber, Nicholas William. The Principles of Constitutionalism. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Barron, David J. “Reclaiming Home Rule.” Harvard Law Review 116, no. 8 (2003): 2255–2386.

Benton, J. Edwin. Counties as Service Delivery Agents: Changing Expectations and Roles. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2002.

Benton, J. Edwin. “County Government.” In Encyclopedia of Public Administration and Public Policy, edited by Evan Berman, 261–266. Routledge, 2003.

Brewer, Albert P. “Constitutional Revision in Alabama: History and Methodology.” Alabama Law Review 48 (1996).

Briffault, Richard. “Home Rule for the Twenty-First Century.” The Urban Lawyer 36, no. 2 (2004): 253–272.

Carr, Jered B. “What Have We Learned About the Performance of Council-Manager Government? A Review and Synthesis of the Research.” Public Administration Review 75, no. 5 (2015): 673–689.

Coulter, Rory, and Jacqueline Scott. “What Motivates Residential Mobility? Re-Examining Self-Reported Reasons for Desiring and Making Residential Moves.” Population, Space and Place 21, no. 4 (2015): 354–371.

Coulton, Claudia, Brett Theodos, and Margery A. Turner. “Residential Mobility and Neighborhood Change: Real Neighborhoods Under the Microscope.” Cityscape 14, no. 3 (2012): 55–89.

Crowder, Kyle. “The Racial Context of White Mobility: An Individual-Level Assessment of the White Flight Hypothesis.” Social Science Research 29, no. 2 (2000): 223–257.

Dinan, John. “State Constitutional Initiative Processes and Governance in the Twenty-First Century.” Chapman Law Review 19 (2016): 61.

Duke, Daniel L. “Organizing Education: Schools, School Districts, and the Study of Organizational History.” Journal of Educational Administration 53, no. 5 (2015): 682–697.

Durning, Dan. “Consolidated Governments.” Encyclopedia of Public Administration and Public Policy 1 (2003).

Emanuel, Rahm. The Nation City: Why Mayors Are Now Running the World. Vintage, 2021.

Faulk, Dagney Gail, and Michael J. Hicks. Local Government Consolidation in the United States. Cambria Press, 2011.

Feiock, Richard C., Christopher M. Weible, David P. Carter, Cali Curley, Aaron Deslatte, and Tanya Heikkila. “Capturing Structural and Functional Diversity Through Institutional Analysis: The Mayor Position in City Charters.” Urban Affairs Review 52, no. 1 (2016): 129–150.

Frederickson, H. George, Curtis Wood, and Brett Logan. “How American City Governments Have Changed: The Evolution of the Model City Charter.” National Civic Review 90 (2001): 3.

Ghazali, Ezlika M., Elaine Yee-Ling Ngiam, and Dilip S. Mutum. “Elucidating the Drivers of Residential Mobility and Housing Choice Behaviour in a Suburban Township via Push–Pull–Mooring Framework.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 35 (2020): 633–659.

Heikkila, Tanya, and Kimberley Roussin Isett. “Citizen Involvement and Performance Management in Special-Purpose Governments.” Public Administration Review 67, no. 2 (2007): 238–248.

Kavanagh, Shayne. “Does Consolidating Local Governments Work?” Government Finance Officers Association, 2020. https://gfoaorg.cdn.prismic.io/gfoaorg/d6e13e48-5380-4c04-9207-ca985d94bbdd_LocalGovernmentFragmentation-DoesConsolidationWork_Nov2020.pdf.

Kemp, Roger L., ed. Model Government Charters: A City, County, Regional, State, and Federal Handbook. McFarland, 2003.

Krane, Dale, Platon N. Rigos, and Melvin Hill. Home Rule in America: A Fifty-State Handbook. CQ Press, 2001.

Leal, David L., Valerie Martinez-Ebers, and Kenneth J. Meier. “The Politics of Latino Education: The Biases of At-Large Elections.” Journal of Politics 66, no. 4 (2004): 1224–1244.

Lee, Barrett A., R. Salvador Oropesa, and James W. Kanan. “Neighborhood Context and Residential Mobility.” Demography 31, no. 2 (1994): 249–270.

Leland, Suzanne M., and Gary A. Johnson. “Consolidation as a Local Government Reform.” In City-County Consolidation and Its Alternatives: Reshaping the Local Government Landscape: Reshaping the Local Government Landscape, edited by Jered B. Carr and Richard C. Feiock, 25–38. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2016.

Libonati, Michael E. “State Constitutions and Local Government in the United States.” In The Place and Role of Local Government in Federal Systems, edited by Nico Steytler, 11–26. Johannesburg: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2005.

Morgan, David R., and Sheilah S. Watson. “Policy Leadership in Council-Manager Cities: Comparing Mayor and Manager.” Public Administration Review 52, no. 5 (1992): 438–446.

National League of Cities. “Cities 101—Forms of Local Government.” 2024. https://www.nlc.org/resource/cities-101-forms-of-local-government/.

Ohio Laws and Administrative Rules: Legislative Service Commission. “Ohio Revised Code, Section 955.01 Registration of Dogs.” 2014. https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-955.01.

Pelchen, Lexie. “Moving Statistics and Trends for 2024.” Forbes, April 24, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/home-improvement/moving-services/annual-moving-trend-forecast/.

Rice, Bradley R. “Commission Form of City Government.” Texas State Historical Association, 1995. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/commission-form-of-city-government.

Richardson, Jesse J., Jr. “Dillon’s Rule Is from Mars, Home Rule Is from Venus: Local Government Autonomy and the Rules of Statutory Construction.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 41, no. 4 (2011): 662–685.

Sell, Samantha. “Running an Effective School District: School Boards in the 21st Century.” Journal of Education 186, no. 3 (2006): 71–97.

Stein, Robert M. “Arranging City Services.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 3, no. 1 (1993): 66–92.

Stephan, G. Edward. “Variation in County Size: A Theory of Segmental Growth.” American Sociological Review (1971): 451–461.

Stewart, William Histaspas. The Alabama State Constitution. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Stren, Richard, and Abigail Friendly. “Big City Mayors: Still Avatars of Local Politics?” Cities 84 (2019): 172–177.

Tarr, G. Alan. Understanding State Constitutions. Princeton University Press, 2018.

Tax Foundation. “Taxes in Idaho.” 2025. https://taxfoundation.org/location/idaho/.

Todd, Jason Douglas, Curtis Bram, and Arvind Krishnamurthy. “Do At-Large Elections Reduce Black Representation? A New Baseline for County Legislatures.” Electoral Studies 88 (2024): 102750.

Trounstine, Jessica, and Melody E. Valdini. “The Context Matters: The Effects of Single-Member Versus At-Large Districts on City Council Diversity.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 3 (2008): 554–569.

Waugh, William L. “County Government as the ‘Administrative Arm’ of State Government.” In Handbook of Local Government Administration, 403–418. Routledge, 2019.

Woldoff, Rachael A. White Flight/Black Flight: The Dynamics of Racial Change in an American Neighborhood. Cornell University Press, 2017.

Zhang, Yahong, and Richard C. Feiock. “City Managers’ Policy Leadership in Council-Manager Cities.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20, no. 2 (2010): 461–476.

Zug, Charles U. “The Historical Presidency: ‘Giving Government to Business’: Dwight Eisenhower and the Federal Highway Act.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2023): 120–136.

- Libonati, “State Constitutions and Local Government,” 11. ↵

- Tarr, Understanding State Constitutions. ↵

- Briffault, “Home Rule,” 253–272; Richardson, “Dillon’s Rule Is from Mars,” 662–685. ↵

- Brewer, “Constitutional Revision,” 583; Stewart, Alabama State Constitution. ↵

- Frederickson, Wood, and Logan et al., “How American City Governments Have Changed,” 3. ↵

- Tarr, Understanding State Constitutions. ↵

- Dinan, “State Constitutional Initiative Processes,” 61. ↵

- Barber, Principles of Constitutionalism. ↵

- Barron, “Reclaiming Home Rule,” 2255–2386. ↵

- Krane, Rigos, and Hill et al., Home Rule in America. ↵

- Brewer, “Constitutional Revision,” 583; Stewart, Alabama State Constitution. ↵

- Heikkila and Isett, “Citizen Involvement,” 238–248. ↵

- Duke, “Organizing Education,” 682–697. ↵

- Sell, “Running an Effective School,” 71–97. ↵

- Benton, “County Government,” 261–266. ↵

- Waugh, “County Government,” 403–418. ↵

- Stephan, “Variation in County Size,” 451–461. ↵

- Benton, “County Government,” 261–266. ↵

- Benton, “County Government,” 261–266. ↵

- Benton, Counties as Service Delivery Agents. ↵

- Ohio Laws and Administrative Rules: Legislative Service Commission, “Ohio Revised Code.” ↵

- Stein, “Arranging City Services,” 66–92. ↵

- Kavanagh, “Does Consolidating Local Governments Work?” ↵

- Crowder, “Racial Context,” 223–257; Woldoff, White Flight/Black Flight. ↵

- Zug, “Historical Presidency,” 120–136. ↵

- Durning, “Consolidated Governments.” ↵

- Leland and Johnson, “Consolidation.” ↵

- Faulk and Hicks, Local Government Consolidation. ↵

- Frederickson, Wood, and Logan et al., “How American City Governments Have Changed,” 3. ↵

- Kemp, Model Government Charters. ↵

- Rice, “Commission Form of City Government.,” Texas State Historical Association. ↵

- National League of Cities, “Cities 101.” ↵

- National League of Cities, “Cities 101.” ↵

- Morgan and Watson, “Policy Leadership,” 438–446. ↵

- Carr, “What Have We Learned?,” 673–689. ↵

- Zhang and Feiock, “City Managers’ Policy,” 461–476. ↵

- Stren and Friendly, “Big City Mayors,” 172–177. ↵

- Emanuel, Nation City; Feiock et al., “Capturing Structural and Functional Diversity,” 129–150. ↵

- Pelchen, “Moving Statistics.” ↵

- Coulter and Scott, “What Motivates Residential Mobility?,” 354–371; Lee, Oropesa, and Kanan et al., “Neighborhood Context and Residential Mobility,” 249–270. ↵

- Coulton, Theodos, and Turner et al., “Residential Mobility,” 55–89; Ghazali, Ngiam, and Mutum et al., “Elucidating the Drivers,” 633–659. ↵

- Trounstine and Valdini, “Context Matters,” 554–569. ↵

- Abott and Magazinnik, “At-Large Elections,” 717–733; Leal, Martinez-Ebers, and Meier et al., “Politics of Latino Education,” 1224–1244; Todd, Bram, and Krishnamurthy et al., “Do At-Large Elections Reduce?,” 102750. ↵

- Trounstine and Valdini, “Context Matters,” 554–569. ↵