7 Direct Democracy

Gregory Shufeldt

Chapter Summary

The United States follows a model of representative democracy, where citizens elect public officials to make decisions on their behalf. Direct democracy is a unique institutional feature available in some states to engage constituents directly with policymaking. Roughly half of all states utilize mechanisms like initiatives, referendums, and recalls allowing voters direct input. This chapter discusses the differences between direct and representative democracy, differences in direct democratic institutions across the states, the origins of direct democracy, and arguments for and against direct democracy.

Student Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Recognize the differences between representative and direct democracy.

- Compare and contrast among the three major institutions (initiative, referendum, and recall) of direct democracy.

- Identify differences among the four major types of initiatives (statutory, constitutional, direct, and indirect).

- Identify differences between the two major types of referendum (legislative and popular).

- Explain the origins of direct democracy in the United States.

- Analyze how state variation in the process of direct democracy is associated with state differences in the frequency of its use.

- Evaluate both arguments in favor of and opposed to direct democracy.

- Assess the educative effects of direct democracy.

- Evaluate recent efforts by state governments to limit how citizens are able to utilize direct democracy.

Focus Questions

These questions illustrate the main concepts covered in the chapter and should help guide discussion as well as enable students to critically analyze and apply the material covered.

In what ways have the founding fathers been successful in designing a government that limits the role of popular opinion in governance? How have those institutions they created to minimize the “passions of the people” changed or remained over time?

How are states different in their use of direct democratic institutions?

How difficult should the process be for an initiative, referendum, or recall to make the ballot?

What are some of the arguments in favor of direct democracy? What are some of the arguments against it?

What Is Direct Democracy?

When Benjamin Franklin was exiting the Constitutional Convention, a woman by the name of Elizabeth Willing Powel asked him, “What have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Franklin replied, “A republic if you can keep it.”[1] The United States was established as a republic or representative democracy where citizens play an active role in government by voting for representatives to make decisions in government on their behalf. While some argue that being established as a republic precludes being a democracy, that is a false contrast or a distinction without a difference.[2]

We’re not a democracy.

— Mike Lee (@SenMikeLee) October 8, 2020

Democracy isn’t the objective; liberty, peace, and prospefity are. We want the human condition to flourish. Rank democracy can thwart that.

— Mike Lee (@SenMikeLee) October 8, 2020

Figure 7.1 Senator Mike Lee’s Tweets

Source: “We’re not a democracy.” and “Democracy isn’t the objective; liberty, peace, and prospefity [sic] are. We want the human condition to flourish. Rank democracy can thwart that.” by Mike Lee (@SenMikeLee) on x.com (formerly Twitter). Embedded per https://developer.x.com/en/developer-terms/display-requirements.

To the extent the republican form of government in the United States is not considered a democracy, that is in contrast to a pure or direct democracy, a system of government where citizens vote directly on policies rather than indirectly through elected officials. Democracy has its roots in ancient Greece. The word democracy stems from the Greek word demos (which means “the people”) and kratos (which means “rule”)—literally, “rule by the people.”

The founding fathers chose to pursue a representative democracy rather than a direct democracy based on their concerns about human nature, mob rule, and tyrannical majorities. James Madison wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”[3] Almost two centuries later, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously remarked that “it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”[4] The founders certainly had these types of concerns in mind, as previously described in Chapter 2; the Constitution structured a government in an attempt to balance majority rule with minority rights. Through a system of separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism, the Constitution was designed to ensure that too much power was not concentrated in a single institution or with a single elected official. Yet a republican form of government would best ensure the protection of rights and liberties.

At the time the Constitution was ratified, only members of the US House of Representatives were directly elected by citizens. Senators were indirectly elected by state legislatures until the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. Supreme Court justices receive lifetime appointments without any direct citizen involvement in their nomination or retention. Even the process of amending the Constitution in Article V does not provide a direct way for citizens to participate. Twenty-six of the twenty-seven amendments to the Constitution have been ratified by receiving two-thirds support in each chamber of Congress and at least three-fourths of the country’s state legislatures. There is no process for a national referendum. Voting for the president is the only national vote citizens in the United States take, and even it remains an indirect vote based on the role of the Electoral College in electing the president. So while the federal government follows a representative form of democracy, significant state variation exists in the institutions of direct democracy.

What Are the Different Institutions in Direct Democracy?

While citizens have no direct role or ability to vote for or against prospective amendments to the US Constitution, citizens of nearly every state have the opportunity to affect change to their state constitutions. In forty-nine out of the fifty states, citizens have some sort of role or mechanism to approve proposed state constitutional amendments.[5] Delaware is the sole exception, where the state legislature controls the process without direct voter participation. The rest of this discussion will extend beyond just state constitutional amendments.

The three major forms or types of direct democracy are the initiative, the referendum, and the recall. An initiative is a citizen-driven ballot measure to pass a new policy or to direct the state legislature to vote on said policy. A referendum, the most common form of direct democracy, is when citizens vote on a policy that has already been considered by the state (or local) government. A recall is a vote to remove an elected official before their term expires.

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “Forms of Direct Democracy in the American States.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Forms_of_direct_democracy_in_the_American_states. Map made by author.

Figure 7.2 demonstrates that seventeen of the fifty states have no direct democratic institutions in their states. These states are largely concentrated in the South, mid-Atlantic, and New England. With the exception of Iowa and Texas, states without any direct democratic institutions are east of the Mississippi River. The remaining thirty-three states have some sort of direct democratic institution. Thirteen states possess all three forms (initiative, referendum, and recall). Geographically, with the exception of Michigan, they are all west of the Mississippi River. This geographic pattern will be explored in more detail in the next section (“What Are the Origins of Direct Democracy in the United States?”).

Twenty-four states have some access to the initiative process.[6] The two primary types of initiatives are statutory and constitutional initiatives. Statutory initiatives provide voters the opportunity to pass a new law, whereas constitutional initiatives involve adding language or amending the state constitution. Twenty-one states have the statutory initiative and six have both types, while Florida, Illinois, and Mississippi only have the constitutional initiative. Within these two types of initiatives, differences also exist in whether voters directly or indirectly play a role.

Data Source: National Conference of State Legislatures. “Initiative and Referendum States.” n.d. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/initiative-and-referendum-states. Map made by author.

The first type is known as a direct initiative. This form of direct democracy is what comes to mind for most when thinking about the initiative. Here citizens or organized groups create a measure that they would like to be placed on the ballot. This process involves collecting a sufficient number of signatures from registered voters throughout the state to qualify for ballot access. If the initiative successfully makes it onto the ballot, voters directly consider it by voting yes or no. This stands in contrast to an indirect initiative, where an additional step is involved. Prior to the initiative being placed on the ballot, it is first considered by the state legislature. If the legislature approves the initiative, it becomes law. If, however, the legislature rejects the initiative, then voters get the chance to vote on the measure to override the state legislature.

Of the twenty-one states with the statutory initiative, twelve of them utilize the direct initiative. Seven states possess the indirect initiative. Utah and Wyoming voters can utilize both the direct and indirect processes. Of the three states with only the constitutional initiative, Florida and Illinois directly place the ballot measure before voters.

In Mississippi, they have utilized the indirect initiative since 1992. However, the process in Mississippi has been in limbo since 2021.[7] The Mississippi Constitution, specifically section 273(3), requires that citizens seeking to place a measure on the ballot gather one-fifth of their required signatures from each of Mississippi’s five congressional districts. After successfully submitting enough signatures to get a medical marijuana initiative on the ballot, the Mississippi Supreme Court struck down the measure, identifying that it failed to meet the signature requirements because Mississippi lost one of its five congressional districts due to redistricting after the 2000 Census: “Whether with intent, by oversight, or for some other reason, the drafters of section 273(3) wrote a ballot-initiative process that cannot work in a world where Mississippi has fewer than five representatives in Congress.”[8] This 2021 decision is the second time the Mississippi Supreme Court has struck down the initiative, having done so previously in 1922, overturning the will of voters from 1914.

The 2024 election is poised to feature twenty-three statutory initiatives and thirteen constitutional initiatives. These thirty-four initiatives cover many diverse policy areas, including abortion, tax reform, raising the minimum wage, marijuana legalization, election reform, and changes to the initiative process itself.[9]

The citizen-initiative process is quite similar to the popular referendum process. Also known as a veto referendum, citizens initiate a process to create a ballot measure asking voters to consider approving or repealing a piece of legislation already passed by their state legislature. Twenty-three states possess veto referendums. Citizens enjoy a very high success rate (65 percent) of repealing legislation passed by state legislatures if they are able to make it to the ballot.[10] Some examples of recently repealed measures include the Maine state legislature attempting to repeal the use of ranked-choice voting and a Missouri law that attempted to make the Show-Me-State a right-to-work state.

|

State |

Total Number of |

Number of Laws Upheld |

Number of Laws Repealed |

|

WA |

39 |

8 (21%) |

31 (79%) |

|

OR |

68 |

24 (35%) |

44 (65%) |

|

CA |

50 |

21 (42%) |

29 (58%) |

|

AK |

4 |

2 (50%) |

2 (50%) |

|

NV |

2 |

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

|

ID |

7 |

3 (43%) |

4 (57%) |

|

WY |

1 |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

|

MT |

13 |

4 (31%) |

9 (69%) |

|

CO |

14 |

4 (29%) |

10 (71%) |

|

UT |

4 |

0 (0%) |

4 (100%) |

|

AZ |

35 |

19 (54%) |

16 (46%) |

|

NM |

3 |

2 (67%) |

1 (33%) |

|

ND |

75 |

28 (37%) |

47 (63%) |

|

SD |

46 |

13 (28%) |

33 (72%) |

|

NE |

17 |

6 (35%) |

11 (65%) |

|

OK |

20 |

8 (40%) |

12 (60%) |

|

MO |

26 |

1 (4%) |

25 (96%) |

|

AR |

9 |

1 (11%) |

8 (89%) |

|

MI |

10 |

1 (10%) |

9 (90%) |

|

OH |

13 |

2 (15%) |

11 (85%) |

|

MD |

18 |

11 (61%) |

7 (39%) |

|

MA |

22 |

12 (55%) |

10 (45%) |

|

ME |

31 |

13 (42%) |

18 (58%) |

The other form of referendum is the legislative referendum. Rather than a process initiated by the voters, the state legislature poses the question for voters to consider. All fifty states possess the legislative referendum, with many required by law to put measures in front of voters to amend the state constitution or make tax reforms.[11] Voters across the fifty states saw more than one hundred referred ballot measures in 2024.[12] For example, California voters will vote on Proposition 3 to repeal a prior 2008 vote (Proposition 8) that defined marriage as a union between one man and one woman. The United States is one of the rare advanced industrial democracies to not have a national legislative referendum process.[13]

The final institution of direct democracy is the recall. Twenty states have the ability to recall an elected official before their term expires. Seven states possess solely the recall with no other form of direct democracy in their state. Wanting to remove an elected official before their term ends is easier said than done, as most attempts at a recall never make it to the ballot. Through the first six months of 2024, 100 out of 164 attempts did not make the ballot. Out of the 64 that made the ballot, 38 were removed from office (i.e., the recall was successful), 6 quit (the recall had the intended effect), and 20 attempts were defeated (the incumbent remained in office).[14]

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “Political Recall Efforts.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Political_recall_efforts. Table made by author.

Compared to statewide office holders, more attempts (and more success) to recall elected officials happen at the local level. Members of school boards and city councils are more likely to face (and lose) recall compared to governors or state legislatures. Only two governors have ever successfully been recalled in US history. The most prominent and recent successful recall was when California voters removed Governor Gray Davis in 2003. Davis, a Democrat, was first elected in 1998 with almost 58 percent of the vote. In 2002, he was reelected with 47 percent of the vote. However, less than one year after receiving a second term, Davis was recalled with 55 percent of the vote. He was recalled, in part, due to an energy crisis and budget deficit associated with the dot-com bubble burst.[15] In a subsequent election, he was replaced by actor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[16]

Source: “Gray Davis” by Neon Tommy on Flickr / CC BY-SA.

More recently, many partisan activists have sought to recall governors, such as Scott Walker in Wisconsin in 2012 and Gavin Newsom in California in 2021.[17] After expensive and nasty partisan battles, both Walker and Newsom were able to remain in office after unsuccessful recall efforts.

What Are the Origins of Direct Democracy in the United States?

The roots of direct democracy in the United States predate the official founding as an independent country by more than one hundred years. Many New England states, then colonies, began hosting regular town hall meetings. These participatory meetings facilitate a model of deliberative democracy, where citizens engage in open discussion before publicly voting on matters of civic interest. However, how truly open, inclusive, and participatory they were is open to debate.[18] Rather than hiding behind the safety and anonymity of the secret ballot or behind the “too-big” mechanisms of government institutions, the town hall format “forced civility.” Today, these meetings occur annually as the sole method of governing. For example, the residents of Elmore, Vermont, voted in 2023 to keep their town hall tradition alive by more than a 2–1 margin.[19]

Figure 7.6 – New England Town Hall Meetings

Source: ConcordNHTV. “Town Meeting Day: A New England Tradition.” YouTube, Mar 2, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D61uQw7DeXI. / Embedded with the Standard YouTube License.

Outside of New England, states were slower to implement aspects of direct democracy into their state and local governments. Thomas Jefferson unsuccessfully proposed that Virginia voters should ratify the state’s 1775 constitution. Throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s, many states wrote or rewrote their constitutions and incorporated voter approval, especially for constitutional amendments.[20]

In 1848, Switzerland ratified a new constitution, moving the country from a confederacy to a federal system of government, as described in Chapter 2. As part of this new government, Swiss citizens were given the right to vote in popular initiatives, mandatory (legislative) referendums, and optional (popular) referendums.[21] While the US did not follow suit, Congress did require that all states admitted to the union after 1857 must provide voters the ability to ratify their state constitutions.

The late 1800s and early 1900s mark the period when political parties were perhaps the strongest in our country’s history.[22] Jobs were allocated, and many public services were provided solely to partisan supporters based on a system of patronage. This Gilded Age was characterized by soaring economic growth, rapid urbanization, rising income inequality, and rampant political corruption, often at the hands of party bosses. As a result, many citizens sought change. The Populist Party became the first third party to win Electoral College votes since the end of the Civil War, when they carried five states and twenty-two Electoral College votes.[23] Four years later, many of the ideas of the Populist Party were consolidated into the Democratic Party’s platform and William Jennings Bryan’s nomination as president.

The Progressive Era, more broadly, included all sorts of “good government” reforms. States switched to the secret, or Australian, ballot rather than ballots printed and distributed by political parties. Patronage was replaced with a merit system as part of broader civil service reforms. The direct election of US Senators was added to the Constitution when the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified in 1913. Women were granted the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. Parties began to utilize primaries to pick candidates for the general election.

During the Progressive Era, direct democracy began to spread across the United States. The Swiss model was replicated first by South Dakota in 1897. Returning to Figure 7.2, the vast majority of states that implemented direct democracy were geographically west of the Mississippi River. These states were more likely to experience competition between the two major parties (Democrats and Republicans) but also saw third parties (like the Populist Party) enjoy a good deal of success.[24]

|

State |

Year Approved |

|

South Dakota |

1898 |

|

Utah |

1900 |

|

Oregon |

1902 |

|

Montana |

1906 |

|

Oklahoma |

1907 |

|

Missouri |

1908 |

|

Maine |

1908 |

|

Colorado |

1910 |

|

Arkansas |

1910 |

|

California |

1911 |

|

Arizona |

1911 |

|

Nebraska |

1912 |

|

Idaho |

1912 |

|

Nevada |

1912 |

|

Ohio |

1912 |

|

Washington |

1912 |

|

Michigan |

1913 |

|

Mississippi |

1914 |

|

North Dakota |

1914 |

|

Massachusetts |

1918 |

|

Alaska |

1956 |

|

Florida |

1968 |

|

Wyoming |

1968 |

|

Illinois |

1970 |

Twenty of the twenty-four states that currently have the initiative added it between 1898 and 1918. Eighty-three percent of all the states with the initiative added it during that twenty-year window. Illinois was one of the last states to add the initiative in 1970. As previously described, Mississippi adopted the initiative for a second time in 1992, only to have the state supreme court rule it to be effectively impossible for citizens to gather sufficient signatures to get an initiative on the ballot.[25] While some progress has been made in adding the initiative or other forms of direct democracy to additional states, politicians seem unlikely and unwilling to give voters the chance to participate in direct democracy. As succinctly articulated by a Texas Republican explaining his party’s shift from supporting to opposing direct democracy in the state, “If you’re out of government, you’re in favor of initiatives. If you’re in government, they become not so appealing.”[26]

How Does the Initiative Process Work, and How Is It Different State by State?

Having established that there is significant state variation in the existence of direct democracy across the fifty states, it is also worthwhile to dig deeper to examine further differences. Not all states utilize direct democracy at the same rate, and they have very different rules and regulations governing its use. In 1978, California voters approved Proposition 13 by almost a 2–1 margin, drastically limiting future property tax increases and requiring supermajority support for additional tax increases.[27] This led many to call for a “taxpayer revolt,” which sparked many similar initiatives and referendums across the country.

As depicted in Figure 7.7, the last forty years have seen a significant growth in the number of ballot measures. However, the trend appears to be slowing down in the last few election cycles, as many states have passed legislation making it harder for initiatives to reach the ballot.

Data Source: National Conference of State Legislatures. “Statewide Ballot Measures Database.” n.d. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/statewide-ballot-measures-database; Initiative and Referendum Institute. “Direct Democracy Historical Database.” n.d. Graph made by author.

While the number of initiatives has risen over the last half-century, the use of the initiative is uneven across the twenty-four states that feature this institution. The five states that most frequently utilize the initiative (California, Oregon, Colorado, Washington, and Arizona) account for 53 percent of all initiatives in our country’s history. The top ten states account for more than 75 percent of all initiatives.

|

State |

Number of Initiatives |

|

California |

501 |

|

Oregon |

440 |

|

Colorado |

397 |

|

Washington |

342 |

|

Arizona |

209 |

|

Missouri |

206 |

|

North Dakota |

205 |

|

Arkansas |

186 |

|

Massachusetts |

153 |

|

Montana |

100 |

|

Oklahoma |

99 |

|

Ohio |

97 |

|

Florida |

96 |

|

Michigan |

95 |

|

South Dakota |

86 |

|

Maine |

81 |

|

Nevada |

79 |

|

Nebraska |

69 |

|

Alaska |

59 |

|

Idaho |

37 |

|

Utah |

23 |

|

Mississippi |

12 |

|

Wyoming |

7 |

|

Illinois |

1 |

In general, the states with the most use have the easiest time accessing it and are least hampered by the state legislature.[28] Shaun Bowler and Todd Donovan created a six-point index for how difficult it is for an initiative to qualify for the ballot. Higher scores are associated with greater levels of difficulty. The general procedure for how the initiative process works is articulated in the following paragraphs with references made to Bowler and Donovan’s index.[29]

|

State |

Qualification Difficulty Score |

Legislative Insulation Index |

|

Oregon |

0 |

3 |

|

California |

1 |

1 |

|

Colorado |

1 |

4 |

|

North Dakota |

1 |

3 |

|

Arkansas |

2 |

2 |

|

Ohio |

2 |

6 |

|

Michigan |

2 |

3 |

|

South Dakota |

2 |

4 |

|

Idaho |

2 |

4 |

|

Utah |

2 |

4 |

|

Arizona |

3 |

3 |

|

Washington |

3 |

4 |

|

Oklahoma |

3 |

4 |

|

Montana |

3 |

6 |

|

Missouri |

3 |

6 |

|

Massachusetts |

3 |

8 |

|

Nebraska |

4 |

6 |

|

Maine |

4 |

8 |

|

Nevada |

4 |

5 |

|

Florida |

4 |

6 |

|

Illinois |

4 |

5 |

|

Alaska |

5 |

6 |

|

Mississippi |

5 |

7 |

|

Wyoming |

6 |

9 |

The first item that is considered part of Bowler and Donovan’s index is whether the state allows both statutory and constitutional initiatives (0) or only one of the two types of initiatives (1). As previously discussed, the last three states to add the initiative (Florida, Illinois, and Mississippi) only add constitutional, and not statutory, initiatives.

Once an idea is generated—whether by active citizens, organized interest groups, or even the state legislature (in the instances of legislative referendums), a proposal is submitted to the appropriate state official for review. This preliminary filing includes draft language that supporters would like to see on the ballot.[30] In most states, two or more government officials or entities play a role in drafting the language that appears on the ballot and is distributed to voters. The most common elected officials are the state legislature (or some committee of the legislature), the attorney general, or the secretary of state.

Figure 7.8 – Responsibility for Ballot Language

Data Source: Boldt, A. “Direct Democracy in the States: A 50-State Survey of the Journey to the Ballot.” State Democracy Research Initiative, University of Wisconsin Law School. 2023. . Graph made by author.

Data Source: Boldt, A. “Direct Democracy in the States: A 50-State Survey of the Journey to the Ballot.” State Democracy Research Initiative, University of Wisconsin Law School. 2023. . Graph made by author.

https://pressbooks.palni.org/theexcitingdynamicsofstateandlocalgovernment/wp-content/uploads/sites/79/2025/07/Figure-7.8.png

Part of what the government reviews is whether the proposed policy is appropriate for the initiative. The second part of Bowler and Donovan’s index is whether there are substantive subject restrictions. Seven states (Alaska, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Montana, Ohio, and Wyoming) have specific limits on the types of policies the initiative can and cannot address.[31] Some of these restrictions are making appropriations (dictating how state money will be spent), modifying judicial proceedings, or infringing upon rights or liberties spelled out in the state’s constitution.

Sixteen states also include single-subject rules as part of their initiative process.[32] This restriction limits initiatives to address a single policy area to prevent logrolling—that is, preventing groups from combining initiatives together in order to garner additional support. For example, groups in Missouri interested in raising the minimum wage and legalizing recreational marijuana would not be permitted to combine forces in a single initiative. Voters must consider each initiative on its own merit.

As part of the official review, the appropriate government representative drafts an official title and the summary language that would appear on the ballot. The process of drafting language can be contentious and litigious (i.e., end up being the subject of a lawsuit). Who is writing the ballot language often shapes whether the perspective is sympathetic to supporters or opponents, whether it is neutral, and how accessible or understandable the language is for the average voter.[33]

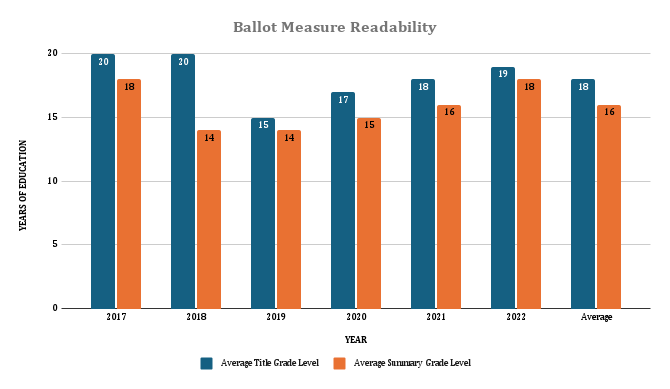

In recent years, Ballotpedia has started to assess the average grade level voters would need to possess in order to fully understand ballot titles and language.[34] The average reading level to understand the title (which averages 57 words) between 2017 and 2022 is eighteen (two years of postgraduate education). The average reading level to understand the summary on the ballot (which averages 193 words) is sixteen (a senior in college). As of the 2020 Census, only 38 percent of people over the age of twenty-five possess at least a bachelor’s degree. While citizens with a college degree are more likely to vote than adults without a college degree and are overrepresented among regular voters, a substantial number of voters have no college degree.[35]

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “Ballot Measure Readability Scores, 2022.” n.d. Graph made by author.

Once supporters have filed their proposed initiative, it has been reviewed by the appropriate government source, and the formal ballot title and summary are prepared, the next step in the process is collecting signatures to ensure that the measure has enough support to qualify for the ballot. The remaining four components of Bowler and Donovan’s ballot access index are (1) whether the length of time supporters have to collect signatures is limited, (2) whether signatures must adhere to geographic distribution requirements, (3) whether the proportion of signatures required is at least 7 percent, and (4) whether the proportion of signatures required is more than 10 percent.

Of the twenty-four states that possess the initiative, fourteen of them have a signature distribution requirement.[36] With the exception of Colorado, four of the five states with the most initiatives over the last century do not require signatures to come from any specific geography within the state. This makes it easier for signature gatherers to concentrate on dense, urban populations or communities where support is more readily available. Florida, Missouri, Mississippi, and Nevada base their signature requirements on congressional districts throughout the state. As previously mentioned, Mississippi’s initiative is currently in flux, since the signature requirement warrants signatures from five congressional districts even though the state only has four since redistricting after the 2020 Census. Arkansas, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Ohio, and Wyoming utilize counties for the geographic requirement. The remaining five states (Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and Utah) require signatures to be dispersed throughout state legislative districts. Maryland and New Mexico have signature requirements for their popular referendum but do not have the initiative in their states.

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “Signature Distribution Requirements for Ballot Initiatives.” n.d. Map made by author.

Increasing the signature distribution requirements is a common way that state governments attempt to limit the ability of citizens to utilize the initiative. In 2023, Ohio voters controversially were asked to consider Issue 1, which would have doubled the geographic requirement from half (44) to all (88) counties. It also would have eliminated the “cure period,” where supporters have ten days to submit additional signatures if their initial submission fails to meet the signature and geographic distribution requirements. Voters rejected this measure with 57 percent of the vote.[37]

The sheer volume of signatures required, especially if states have high thresholds for geographic distributions, often leaves supporters of initiatives relying on paid signature gatherers. This is even more pronounced depending on the window in which supporters can collect signatures, which ranges from ninety days to an unlimited amount of time.[38] Colorado attempted to limit the use of paid signature gatherers, but this was struck down in the US Supreme Court case Meyer v. Grant for violating the First Amendment’s protection of political speech.[39]

As a result, many organized interest groups, like the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center (BISC), exist to provide training, strategic advice, and assistance in utilizing paid signature gatherers. While states are unable to prevent signature gatherers from being paid, states do have considerable variation as to whether the signature gatherers must be state residents, whether they can be paid per signature, or whether they can impose other requirements on signature gatherers.[40]

Once the signatures are submitted and the state government reviews them to ensure that they are legitimate and meet any necessary distribution requirements, the next step in the process is determining when voters will get a chance to weigh in on the initiative. Some states require that ballot initiatives be placed on the ballot for the next general election, whereas other states are able to place initiatives on the ballot during either a primary or a special election.[41] As voter turnout is higher in general elections compared to primary or special elections and higher in presidential elections compared to midterm elections, the decision of when to allow voters the opportunity to vote is often a strategic choice.

Prior to the election, many states are required by law to provide additional information about any initiatives and referendums to voters. Of the twenty-four states that utilize the initiative, fifteen of them are required by law to either send a pamphlet with information about the initiatives to registered voters, publicly display the pamphlet, or make it available online.[42]

Finally, voters get a chance to weigh in and vote in favor of or in opposition to the initiative. Most elections in the United States follow the plurality rule, meaning whichever candidate receives the most votes wins the election. This “first past the post” framework allows a candidate to win the election without receiving more than 50 percent of the vote. Since voters are given the choice to vote yes or no on an initiative, rather than voting on two or more candidates, direct democracy largely relies on majority rule: Whichever outcome receives 50 percent plus one vote is the winner.

However, some states utilize supermajority rule, some numerical requirement above a majority, to pass ballot measures.[43] These thresholds are frequently for approving constitutional amendments (whether initiated by citizens or the state legislature) but also for specific policy areas like taxation. In 2022, Arizona voters approved Proposition 132, which increased the majority requirement from a simple majority to 60 percent in order to approve any future tax increases. Another way that states require more than a simple majority to pass a ballot measure is by utilizing a different denominator to measure turnout. Some states do not simply use whether an initiative received 50 percent plus one vote of all votes cast in the given race but rather utilize the total number of registered voters in the state, the total number of votes cast for the highest office, or some other predetermined number. Proponents of these higher thresholds point to the fact that they prevent voters from abstaining on ballot questions and ensure that election outcomes reflect the preferences of all state voters, not just those who cast a ballot on a given question.

Given the states previously mentioned, it is imperative to highlight how much the initiative process varies from state to state. No two states are completely alike when it comes to how citizens are able to utilize the initiative or other forms of direct democracy. The process, however, surely matters. State differences in the rules governing direct democracy are part of the reason why a state like Wyoming has only seven initiatives in the last one hundred years while states like Oregon and California have more than one thousand combined.

What Are the Arguments in Favor and Opposed to Direct Democracy?

Political scientists frequently debate the merits and shortcomings of direct democracy.[44] In this section, some of the more prominent arguments in favor of and opposed to the initiative will be considered.

The first major argument in favor of direct democracy is that it helps overcome the “sins of omission” of representative democracy.[45] Elected officials may be unwilling or unable to turn the public opinion preferences of their constituents into public policy. Given the polarization and gridlock at the national level, many activists turn their attention to the states (and the initiative) to pursue policy goals.[46]

For example, Republicans have a trifecta, where they control both chambers of the state legislature and the governorship, in twenty-three states. Voters in these states elect and reelect Republicans to control all levels of government. However, when given the opportunity to vote for individual policies, voters in these Republican-controlled states have used the initiative to raise the minimum wage, legalize recreational and medicinal marijuana, expand Medicaid, and protect abortion rights.[47]

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “State Government Trifectas.” 2024. https://ballotpedia.org/State_government_trifectas. Map made by author.

Voters via the initiative are also more likely than the elected branches of government to implement “good government” reforms. For example, nineteen of the twenty-one states that adopted term limits for state legislators during the 1990s and 2000s did so via the initiative.[48] Elected officials are less likely to vote themselves out of the job, but citizens are more than willing to do so.

The second major argument in favor of direct democracy is similar to the “sins of omission” in that the presence of the initiative, referendum, and recall acts as a (pardon the expression) “gun behind the door” and forces the elected branches to be more responsive. The rapid advancement of marijuana legislation at the state level is a perfect example. States first utilized the initiative to adopt medicinal marijuana policies and programs before expanding into recreational marijuana in both Republican and Democratic states.[49] Where the initiative was not utilized, it often spurred legislatures to act. While some studies disagree as to the extent that the mere presence of the initiative is associated with greater responsiveness, others point to evidence that suggests that the threat of the initiative forces legislators to act, leads policy to be more closely aligned with public opinion, and leads to the initiative being used more frequently only when the preferences of voters and elected officials diverge.[50]

The initiative plays an important role in agenda setting and shaping the contours of races between candidates for office.[51] After the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade and a woman’s right to have an abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson, many states utilized the initiative to enshrine abortion rights at the state level. Ten states had abortion-related measures on their ballot in the November 2024 general election.[52] Candidates often have to communicate with voters about where they stand on these initiatives. During the 2022 and 2024 cycles, many Republican candidates for office struggled with how to talk about the issue, balancing between downplaying, adjusting, or doubling down on their positions.[53]

One of the primary arguments against direct democracy is concerns about voter competence. To put it bluntly, are voters “dumber than chimps?”[54] While political scientist V. O. Key famously said, “Voters are not fools,” it is dubious to suspect that most voters understand the substance of all ballot measures.[55]

One of the reasons the founding fathers pursued representative democracy rather than democracy was their belief that elected officials would be better able to make decisions to promote the public good rather than just make self-serving decisions. Voters are less likely to be aware or knowledgeable of the various initiatives or referendums on the ballot, let alone make an informed decision.[56] Most voters need to rely on elite cues or endorsements from trusted interested groups, politicians, and political parties to inform how they believe they should vote on a ballot measure.[57]

When voters are uninformed heading to the polls or are unable to understand a ballot measure, they are more likely to default and vote no to preserve the status quo[58]—that is, when they decide to cast a vote at all. Voters experience “voter fatigue” and “roll-off” if the ballot is too long or they are uninformed about the various ballot measures facing them.[59] During the 2022 November general election, more voters cast a ballot for the highest office (whether that is a race for US Senate, governor, or some other office) than for any ballot measure. The median difference in the number of votes between the two types of contests was 70,936.

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “2022 Ballot Measure Election Results.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/2022_ballot_measure_election_results#November_8; US Elections Project. “2022 General Election.” n.d. https://www.electproject.org/2022g. Graph made by author.

Even if voters are aware of and understand the ballot measures before them in any given election, which is often difficult given that the writing of official language is often intended to confuse, they may not be able to handle democracy à la carte. That is, by voting on some (but not all) legislation, citizens may send conflicting messages to their elected officials and produce unintended challenges. Voters, many of whom are symbolically conservative but operationally liberal, can hamstring elected officials by limiting the amount of revenue the government is able to collect while simultaneously approving new spending priorities.[60]

The second major critique of direct democracy is, What if a majority of voters actually gets what they want? If the majority wins, who loses?

First, many express concerns that direct democracy has long abandoned the populist and progressive aims of those who established the institution.[61] The Supreme Court has repeatedly struck down attempts to regulate the amount of money spent supporting and opposing initiatives as a protection of the First Amendment.[62] As a result, interest groups and wealthy donors invest heavily, spending more than $1.24 billion and $1.10 billion in campaign contributions across more than one hundred different statewide ballot measures in the 2020 and 2022 elections, respectively.[63]

The pure majoritarian nature of direct democracy also poses the threat of “tyranny of the majority.” Without many of the features of representative democracy (e.g., separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism), there is little to stop majorities from imposing their will on minorities. Moreover, behind the anonymity of a secret ballot compared to an open roll-call vote on the floor of the state legislature, it is easier for the majority to impose policies and restrict the civil rights of minorities—whether they be rooted in terms of gender, racial or ethnic group, religious identity, or sexual orientation.[64]

That is not to say that these minority groups lose on every ballot measure. When a minority group is the target of a ballot measure, they generally find themselves outnumbered. Over the last thirty years, states have successfully passed ballot measures that ban same-sex marriage, implement anti–affirmative action proposals, restrict the rights of immigrants, and so on. However, on initiatives or referendums where policy preferences cut across demographic groups, members of the majority and historically oppressed or vulnerable groups win at similar rates.[65] As a result, it is argued that direct democracy works for “the many rather than the few.”[66]

The promise of direct or participatory democracy is that it promotes advantages even beyond the direct or instrumental benefits of the policies passed by the citizens.[67]

Living in a state with direct democracy is associated with all sorts of characteristics and virtues associated with democratic citizenship.[68] This includes higher levels of political knowledge and political efficacy, or the belief that citizens can enact meaningful change. Citizens living in states with direct democratic institutions also report higher levels of personal trust and trust in government. The health or quality of democracy also is theoretically higher, as citizens participate and vote in greater numbers in states with direct democracy.

Citizens living in states with direct democracy report being happier and more satisfied with their lives.[69] Arguably, more important as a democratic institution, the vast majority of citizens support direct democracy. A majority of Americans agree with statements like “A democratic system where citizens, not elected officials, vote directly on major national issues to decide what becomes law would be a good way of governing the country” or “Voters should have the right to propose and pass laws through a citizen initiative process.”[70]

While political scientists continue to weigh the benefits and shortcomings of direct democracy, these competing arguments have real-world consequences.[71] What citizens want, however, appears to be increasingly in conflict with their state government. Whether through legislation being considered by state legislatures or legislative referendums placed in front of voters, many states are attempting to roll back and make direct democracy more difficult to utilize.[72]

For these states, they have direct democracy if they can keep it.

Bibliography

Ballot Initiative Strategy Center. “11-State Ballot Initiative Voter Attitudes Research.” n.d. https://ballot.org/11-state-ballot-initiative-voter-attitudes-research/.

Ballotpedia. “Abortion on the Ballot.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Abortion_on_the_ballot#By_year.

Ballotpedia. “Ballot Measure Campaign Finance, 2022.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Ballot_measure_campaign_finance,_2022.

Ballotpedia. “Ballot Measure Readability Scores, 2022.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Ballot_measure_readability_scores,_2022#Historical_readability_scores.

Ballotpedia. “California Proposition 13, Tax Limitations Initiative (June 1978).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_13,_Tax_Limitations_Initiative_(June_1978).

Ballotpedia. “Constitutional Amendment.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Constitutional_amendment#.

Ballotpedia. “Difficulty Analysis of Changes to Laws Governing Ballot Measures.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Difficulty_analysis_of_changes_to_laws_governing_ballot_measure.

Ballotpedia. “Gavin Newsom Recall, Governor of California (2019–2021).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Gavin_Newsom_recall,_Governor_of_California_(2019-2021).

Ballotpedia. “Gray Davis Recall, Governor of California (2003).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Gray_Davis_recall,_Governor_of_California_(2003).

Ballotpedia. “Laws Governing Ballot Initiative Signature Gatherers.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Laws_governing_ballot_initiative_signature_gatherers.

Ballotpedia. “Length of Signature Gathering Periods for Ballot Initiatives.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Length_of_signature_gathering_periods_for_ballot_initiatives.

Ballotpedia. “List of Veto Referendum Ballot Measures.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/List_of_veto_referendum_ballot_measures.

Ballotpedia. “Ohio Issue 1, 60% Vote Requirement to Approve Constitutional Amendments Measure (2023).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Ohio_Issue_1,_60%_Vote_Requirement_to_Approve_Constitutional_Amendments_Measure_(2023).

Ballotpedia. “Ohio Issue 1, Right to Make Reproductive Decisions Including Abortion Initiative (2023).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Ohio_Issue_1,_Right_to_Make_Reproductive_Decisions_Including_Abortion_Initiative_(2023).

Ballotpedia. “Recall Overview.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Recall_overview.

Ballotpedia. “Scott Walker Recall, Wisconsin (2011–2012).” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Scott_Walker_recall,_Wisconsin_(2011-2012).

Ballotpedia. “Signature Distribution Requirements for Ballot Initiatives.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Signature_distribution_requirements_for_ballot_initiatives.

Ballotpedia. “Single-Subject Rule for Ballot Initiatives.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Single-subject_rule_for_ballot_initiatives.

Ballotpedia. “Subject Restrictions for Ballot Initiatives.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Subject_restrictions_for_ballot_initiatives.

Ballotpedia. “Supermajority Requirements for Ballot Measures.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Supermajority_requirements_for_ballot_measures.

Ballotpedia. “2023 and 2024 Abortion-Related Ballot Measures.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/2023_and_2024_abortion-related_ballot_measures.

Ballotpedia. “2024 Ballot Measures.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/2024_ballot_measures.

Barber, B. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. University of California Press, 2003.

Barth, J., C. Burnett., and J. Parry. “Direct Democracy, Educative Effects, and the (Mis)Measurement of Ballot Measure Awareness.” Political Behavior 42 (2020): 1015–1034.

Beauchamp, Z. “Sen. Mike Lee’s Tweets Against ‘Democracy,’ Explained.” Vox, 2020. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/21507713/mike-lee-democracy-republic-trump-2020.

Bernhard, L. “Does Direct Democracy Increase Civic Virtues? A Systematic Literature Review.” Frontiers in Political Science 6 (2024): 1287330.

Biggers, D. Morality at the Ballot: Direct Democracy and Political Engagement in the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Boehmke, F., T. Osborn, and E. Schilling. “Pivotal Politics and Initiative Use in the American States.” Political Research Quarterly 68 (2015): 665–677.

Boldt, A. “Direct Democracy in the States: A 50-State Survey of the Journey to the Ballot.” State Democracy Research Initiative, University of Wisconsin Law School, 2023. https://statedemocracy.law.wisc.edu/direct-democracy/.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. Demanding Choices: Opinion, Voting, and Direct Democracy. University of Michigan Press, 1998.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. “Democracy, Institutions, and Attitudes About Citizen Influence on Government.” British Journal of Political Science 32 (2002): 371–390.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. “Enduring Questions and Unsatisfactory Answers About Direct Democracy.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. The Limits of Electoral Reform. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. “Measuring the Effect of Direct Democracy on State Policy: Not All Initiatives Are Created Equal.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 4 (2004), 345–363.

Bryan, F. Real Democracy: The New England Town Meeting and How It Works. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Carter, S., A. Chapman, and A. Comella. “Politicians Take Aim at Ballot Initiatives.” Brennan Center for Justice, 2024. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/politicians-take-aim-ballot-initiatives.

Churchill, W. “The Worst Form of Government.” International Churchill Society, 2016. https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/the-worst-form-of-government/.

Council of State Governments. “How Ballot Measures Get on the Ballot.” 2023. https://www.csg.org/2023/11/09/how-ballot-measures-get-on-the-ballot/.

Crary, D. “US States Spit on Allowing Citizen Ballot Initiatives.” Associated Press, 2018. https://apnews.com/article/efb5b289cfb544968c5b79c2d0be20f7.

Cummins, J. “Are Initiatives an End-Run Around the Legislative Process? Divided Government and Voter Support for California Initiatives.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 23 (2023): 443–462.

Dave Leip’s Atlas of US Elections. “1892 Presidential General Election Results.” n.d. https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/.

Dobski, B. “America Is a Republic, Not a Democracy.” Heritage Foundation, 2020. https://www.heritage.org/american-founders/report/america-republic-not-democracy.

Donovan, T. “The Promise and Perils of Direct Democracy: An Introduction.” Politics and Governance 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i2.2267.

Donovan, T., D. Smith, T. Osborn, and C. Mooney. State and Local Politics: Institutions and Reform. 4th ed. Cengage, 2015.

Drum, K. “Happy 35th Birthday, Tax Revolt! Thanks for Destroying California.” Mother Jones, 2013. https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2013/06/tax-revolt-35th-anniversary-prop-13-california/.

Dyck, J. “New Directions for Empirical Studies of Direct Democracy.” Chapman Law Review 19 (2015): 109–128.

Dyck, J., and E. Lascher. Initiatives Without Engagement: A Realistic Appraisal of Direct Democracy’s Secondary Effects. University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Dyck, J., and S. Pearson-Merkowitz. “Ballot Initiatives and Status Quo Bias.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 19 (2019): 180–207.

Ellis, R. Democratic Delusions: The Initiative Process in America. University Press of Kansas, 2002.

Elmendorf, C., and D. Spencer. “Are Ballot Titles Biased? Partisanship in California’s Supervision of Direct Democracy.” UC Irvine Law Review 3 (2013): 511–549.

Elvin, R. “Is America a Democracy or a Republic? Yes, It Is.” National Public Radio, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/10/1122089076/is-america-a-democracy-or-a-republic-yes-it-is.

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. “Direct Democracy.” 2021. https://www.eda.admin.ch/aboutswitzerland/en/home/politik-geschichte/politisches-system/direkte-demokratie.html#.

Ferraiolo, K. “State Policy Activism via Direct Democracy in Response to Federal Partisan Polarization.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 47 (2017): 378–402.

Fuller, J. “Why Are Ballot Measures So Darn Confusing? Because They Are Supposed to Be.” The Washington Post, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2014/08/05/why-are-ballot-measures-so-darn-confusing-because-they-are-supposed-to-be/.

Gamble, B. “Putting Civil Rights to a Popular Vote.” American Journal of Political Science 41 (1997): 245–269.

Gerber, E. The Populist Paradox: Interest Group Influence and the Promise of Direct Democracy. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Grossman, M., and D. Hopkins. Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Guttmacher Institute. “State Bans on Abortion Through Pregnancy.” 2024. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-policies-abortion-bans.

Haider-Markel, D., A. Querze, and K. Lindman. “Lose, Win, or Draw? A Reexamination of Direct Democracy and Minority Rights.” Political Research Quarterly 60 (2007): 304–314.

Hajnal, Z., E. Gerber, and H. Louch. “Minorities and Direct Legislation: Evidence from California Ballot Proposition Elections.” Journal of Politics 64 (2002): 154–177.

Hamilton, A., J. Madison., J. Jay, C. Rossiter, and C. Kessler. The Federalist Papers. Mentor, 1999.

Hannah, A. L., and D. Mallinson. “Defiant Innovation: The Adoption of Medical Marijuana Laws in the American States.” Policy Studies Journal 46, no. 2 (2018): 402–423.

Hartig, H., A. Daniller, S. Keeter., and T. Van Green. “Republican Gains in 2022 Midterms Driven Mostly by Turnout Advantage.” Pew Research Center, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/07/12/republican-gains-in-2022-midterms-driven-mostly-by-turnout-advantage/.

Hayward, S. “The Tax Revolt Turns 20.” Hoover Institution, 1998. https://www.hoover.org/research/tax-revolt-turns-20.

Hicks, W. “Initiatives Within Representative Government: Political Competition and Initiative Use in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 21 (2021): 471–494.

Initiative and Referendum Institute. “The History of the Initiative and Referendum Process in the United States.” n.d. https://www.initiativeandreferenduminstitute.org/history-us-direct-democracy.

Initiative and Referendum Institute. “I&R Historical Timeline.” n.d. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/64fb2a824bc4a564c732b324/t/6547f6da992d3b25ee06bbae/1699215066808/Almanac – I&R Historical Timeline (1).pdf.

Keating, J. 2020. “The Real Reason Why Republicans Keep Saying ‘We’re a Republic, Not a Democracy.’” Slate, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/10/republic-democracy-mike-lee-astra-taylor.html.

Key, V. O. The Responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting, 1936–1960. Harvard University Press, 1966.

Lacombe, S., and F. Boehmke. “The Initiative Process and Policy Innovation in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 21 (2021): 286–305.

Lakoff, G. “Why Are Many Ballot Measures So Confusing?” The New York Times, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/cp/opinion/election-night-2016/why-are-many-ballot-measures-so-confusingly-worded.

Lascher, E., M. Hagen, and S. Rochlin. “Gun Behind the Door? Ballot Initiatives, State Policies, and Public Opinion.” Journal of Politics 58 (1996): 760–775.

Lewis, D. Direct Democracy and Minority Rights: A Critical Assessment of the Tyranny of the Majority in the American States. Routledge, 2012.

Lewis, D., S. Schneider, and W. Jacoby. “The Impact of Direct Democracy on State Spending Priorities.” Electoral Studies 40 (2015): 531–538.

Lupia, A. “Dumber Than Chimps? An Assessment of Direct Democracy Voters.” In Dangerous Democracy? The Battle over Ballot Initiatives in America, edited by L. Sabato, B. Larson, and H. R. Ernst, 66–70. Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

Lupia, A., and J. Matsusaka. “Direct Democracy: New Approaches to Old Questions.” Annual Review of Political Science 7 (2004): 463–482.

Mallinson, D., and A. L. Hannah. “Policy and Political Learning: The Development of Medical Marijuana Policies in the States.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 50, no. 3 (2020): 344–369.

Matsusaka, J. “Direct Democracy Backsliding? Quantifying the Prevalence and Investing Causes 1960–2022.” Initiative and Referendum Institute, 2023. https://www.initiativeandreferenduminstitute.org/research-on-direct-democracy.

Matsusaka, J. For the Many or the Few: The Initiative, Public Policy, and American Democracy. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Miller, J. “‘A Republic If You Can Keep It’: Elizabeth Willing Powel, Benjamin Franklin, and the James McHenry Journal.” Library of Congress Blogs, 2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/manuscripts/2022/01/a-republic-if-you-can-keep-it-elizabeth-willing-powel-benjamin-franklin-and-the-james-mchenry-journal/.

Mulvihill, G., and K. Kruesi. “Arizona and Missouri Join States with Abortion Amendments on the Ballot. What Would the Measures Do?” Associated Press, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/abortion-election-2024-roe-ballot-4403190b898e501b0834053c3417d072.

National Conference of State Legislatures. “Initiative and Referendum Overview and Resources.” 2022. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/initiative-and-referendum-overview-and-resources.

National Conference of State Legislatures. “Initiative and Referendum States.” n.d. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/initiative-and-referendum-states.

National Public Radio. “Gray Davis Reflects on His Recall, as Californians Decide Gov. Newsom’s Fate.” 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/09/12/1036475253/gray-davis-reflects-on-his-recall-as-californians-decide-gov-newsoms-fate.

New, M. “The Tax Revolt Turns 25.” Cato Institute, 2003. https://www.cato.org/commentary/tax-revolt-turns-25.

Nicholson, S. “The Political Environment and Ballot Proposition Awareness.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (2003): 403–410.

Nicholson, S. Voting the Agenda: Candidates, Elections, and Ballot Propositions. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Oyez. “Meyer v. Grant.” n.d. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1987/87-920.

Pateman, C. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Perry, N., and L. Rathke. “In Vermont, ‘Town Meeting’ Is Democracy Embodied. What Can the Rest of the Country Learn from It?” Associated Press, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/democracy-town-meeting-vermont-elections-civility-elmore-11d7d1b63037d054506e77e261aff87c.

Phillips, J. “Does the Citizen Initiative Weaken Party Government in the U.S. States?” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 8 (2008): 127–149.

Piper, K. “California’s Ballot Initiative System Isn’t Working. How Do We Fix It?” Vox, 2020. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/11/6/21549654/california-ballot-initiative-proposition-direct-democracy.

Pittman, A. “‘Democracy Dies Blow by Blow’: How Mississippi’s Supreme Court Killed the Ballot Initiative Twice in 99 Years.” Mississippi Free Press, 2021. https://www.mississippifreepress.org/democracy-dies-blow-by-blow-voters-ask-supreme-court-for-initiative-65-rehearing/.

Pott, M. “Why Republican Voters Support Ballot Initiatives Their Red States Do Not.” FiveThirtyEight, 2022.https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-republican-voters-support-ballot-initiatives-their-red-states-do-not/.

Qvortrup, M. Referendums Around the World. Springer, 2024.

Radcliff, B., and G. Shufeldt. “Direct Democracy and Subjective Well-Being: The Initiative and Life Satisfaction in the American States.” Social Indicators Research 128 (2016): 1405–1423.

Rosenbaum, J. “Abortion Rights on the Ballot May Not Be Bad News for Republicans Everywhere.” National Public Radio, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/04/27/1246609040/abortion-rights-ballot-missouri-republicans.

Rovner, J. “Republican Candidates Are Downplaying Abortion, but It Keeps Coming Up.” National Public Radio, 2024. https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2024/07/01/nx-s1-5023157/abortion-republican-candidates-voting-election-issue.

Sabato, L., B. Larson, and H. Ernst. Dangerous Democracy? The Battle over Ballot Initiatives in America. Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

Simonovits, G., A. Guess, and J. Nagler. “Responsiveness Without Representation: Evidence from Minimum Wage Laws in U.S. States.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (2019): 401–410.

Smith, D., and D. Fridkin. “Delegating Direct Democracy: Interparty Legislative Competition and the Adoption of the Initiative in the American States.” American Political Science Review 102 (2008): 333–350.

Smith, D., and C. Tolbert. Educated by Initiative: The Effects of Direct Democracy on Citizens and Political Organizations in the American States. University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Smith, D., and C. Tolbert. “The Instrumental and Educative Effects of Ballot Measures: Research on Direct Democracy in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 7 (2007): 416–445.

Steck, E., A. Kaczynski, M. Chacón, and P. Gallagher. “Republican Candidates Downplay Past Anti-Abortion Stances Ahead of 2024 Election.” CNN, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2024/04/politics/abortion-rights-republican-2024-election-dg/index.html.

Sundquist, J. Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States. Brookings Institution, 1983.

Thrush, G. “‘We’re Not a Democracy,’ Says Mike Lee, a Republican Senator. That’s a Good Thing, He Adds.” The New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/08/us/elections/mike-lee-democracy.html.

United States Census Bureau. “Census Bureau Releases New Educational Attainment Data.” 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2023/educational-attainment-data.html.

Vollers, A. “Despite GOP Headwinds, Citizen-Led Abortion Measures Could Be on the Ballot in 9 States.” Stateline, 2024. https://stateline.org/2024/06/21/despite-gop-headwinds-citizen-led-abortion-measures-could-be-on-the-ballot-in-9-states/.

Wattenberg, M., I. McAllister, and A. Salvanto. “How Voting Is like Taking an SAT Test: An Analysis of American Voter Rolloff.” American Politics Research 28 (2000): 234–250.

Wike, R., J. Fetterrolf, M. Smerkovich, S. Austin, S. Gubbala, and J. Lippert. “Representative Democracy Remains a Popular Ideal, but People Around the World Are Critical of How It’s Working.” Pew Research Center, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/02/28/representative-democracy-remains-a-popular-ideal-but-people-around-the-world-are-critical-of-how-its-working/.

Wilson, R. “‘If This Thing Qualifies, I’m Toast’: An Oral History of the Gray Davis Recall in California.” The Hill, 2021. https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/556014-if-this-thing-qualifies-im-toast-an-oral-history-of-the-gray-davis-recall/.

Zimmerman, J. The New England Town Meeting: Democracy in Action, Praeger, 1999.

Zuckerman, M. “Mirage of Democracy: The Town Meeting in America.” Journal of Public Deliberation 15 (2019): Article 3.

- Miller, “‘Republic If You Can Keep It.’” ↵

- Beauchamp, “Sen. Mike Lee’s Tweets”; Dobski, “American Is a Republic”; Elvin, “Is America a Democracy?”; Keating, “Real Reason Why”; Thrush, “‘We’re Not a Democracy.’” ↵

- Hamilton et al., Federalist Papers. ↵

- Churchill, “Worst Form of Government.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Constitutional Amendment.” ↵

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Initiative and Referendum States.” ↵

- Pittman, “‘Democracy Dies Blow by Blow.’” ↵

- Pittman, “‘Democracy Dies Blow by Blow.’” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “2024 Ballot Measures.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “List of Veto Referendum Ballot Measures.” ↵

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Initiative and Referendum Overview.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “2024 Ballot Measures.” ↵

- Qvortrup, Referendums Around the World. ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Recall Overview.” ↵

- Wilson, “‘If This Thing Qualifies.’” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Gray Davis Recall”; National Public Radio, “Gray Davis Reflects.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Scott Walker Recall”; Ballotpedia, “Gavin Newsom Recall.” ↵

- Bryan, Real Democracy; Zimmerman, New England Town Meeting; Zuckerman, “Mirage of Democracy.” ↵

- Perry and Rathke, “In Vermont, ‘Town Meeting.’” ↵

- Initiative and Referendum Institute, “I&R Historical Timeline”; Initiative and Referendum Institute, “History of the Initiative.” ↵

- Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, “Direct Democracy.” ↵

- Sundquist, Dynamics of the Party System. ↵

- Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Elections, “1892 Presidential General Election Results.” ↵

- Initiative and Referendum Institute, “I&R Historical Timeline”; Initiative and Referendum Institute, “History of the Initiative”; Smith and Fridkin, “Delegating Direct Democracy,” 333–350. ↵

- Pittman, “‘Democracy Dies Blow by Blow.’” ↵

- Crary, “US States Spit.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “California Proposition 13”; Hayward, “Tax Revolt Turns 20”; New, “Tax Revolt Turns 25”; Drum, “Happy 35th Birthday, Tax Revolt.” ↵

- Bowler and Donovan, “Measuring the Effect,” 345–363. ↵

- The Council of State Governments, “How Ballot Measures Get on the Ballot”; Boldt, “Direct Democracy.” ↵

- The Council of State Governments, “How Ballot Measures Get on the Ballot.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Subject Restrictions for Ballot Initiatives.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Single-Subject Rule for Ballot Initiatives.” ↵

- Fuller, “Why Are Ballot Measures So Darn Confusing?”; Lakoff, “Why Are Many Ballot Measures So Confusing?”; Elmendorf and Spencer, “Are Ballot Titles Biased?,” 511–549. ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Ballot Measure Readability Scores, 2022.” ↵

- United States Census Bureau, “Census Bureau Releases”; Hartig et al., “Republican Gains.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Signature Distribution Requirements.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Ohio Issue 1, 60% Vote.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Length of Signature Gathering.” ↵

- Oyez, “Meyer v. Grant.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Laws Governing Ballot Initiative.” ↵

- Boldt, “Direct Democracy.” ↵

- Boldt, “Direct Democracy.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Supermajority Requirements.” ↵

- Dyck, “New Directions,” 109–128; Smith and Tolbert, “Instrumental and Educative Effects,” 416–445; Lupia and Matsusaka, “Direct Democracy,” 463–482. ↵

- Donovan, Smith, Osborn, and Mooney et al., State and Local Politics. ↵

- Phillips, “Does the Citizen Initiative Weaken?,” 127–149; Ferraiolo, “State Policy Activism,” 378–402; Lacombe and Boehmke, “Initiative Process,” 286–305; Hicks, “Initiatives,” 471–494; Cummins, “Are Initiatives an End-Run,” 443–462. ↵

- Pott, “Why Republican Voters Support”; Simonovits, Guess, and Nagler et al., “Responsiveness Without Representation,” 401–410; Vollers, “Despite GOP Headwinds.” ↵

- Bowler and Donovan, Limits of Electoral Reform. ↵

- Mallinson and Hannah, “Policy and Political Learning,” 344–369; Hannah and Mallinson, “Defiant Innovation,” 402–423. ↵

- Lascher, Hagen, and Rochlin et al., “Gun Behind the Door?,” 760–775; Lewis, Schneider, and Jacoby et al., “Impact of Direct Democracy,” 531–538; Boehmke, Osborn, and Schilling et al., “Pivotal Politics,” 665–677; Simonovits, Guess, and Nagler et al., “Responsiveness Without Representation,” 401–410. ↵

- Nicholson, Voting the Agenda; Smith and Tolbert, Educated by Initiative; Smith and Tolbert, “Instrumental and Educative Effects,” 416–445. ↵

- Ballotpedia, “2023 and 2024 Abortion-Related Ballot Measures.” ↵

- Rovner, “Republican Candidates Are Downplaying Abortion”; Rosenbaum, “Abortion Rights on the Ballot”; Steck et al., “Republican Candidates Downplay.” ↵

- Lupia, “Dumber Than Chimps?” ↵

- Key, Responsible Electorate. ↵

- Nicholson, Voting the Agenda; Barth, Burnett, and Parry et al., “Direct Democracy,” 1015–1034. ↵

- Smith and Tolbert, Educated by Initiative; Lupia and Matsusaka, “Direct Democracy,” 463–482. ↵

- Dyck and Pearson-Merkowitz, “Ballot Initiatives,” 180–207. ↵

- Nicholson, “Political Environment,” 403–410; Wattenberg, McAllister, and Salvanto et al., “How Voting Is lLike Taking an SAT Test”; Bowler and Donovan, Demanding Choices. ↵

- Piper, “California’s Ballot Initiative System”; Grossman and Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics. ↵

- Gerber, Populist Paradox; Ellis, Democratic Delusions; Sabato, Larson, and Ernst et al., Dangerous Democracy? ↵

- Initiative and Referendum Institute, “I&R Historical Timeline.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Ballot Measure Campaign Finance, 2022.” ↵

- Gamble, “Putting Civil Rights to a Popular Vote,” 245–269; Lewis, Direct Democracy and Minority Rights; Haider-Markel, Querze, and Lindman et al., “Lose, Win, or Draw?,” 304–314; Hajnal, Gerber, and Louch et al., “Minorities and Direct Legislation,” 154–177. ↵

- Hajnal, Gerber, and Louch et al., “Minorities and Direct Legislation,” 154–177. ↵

- Matsusaka, For the Many or the Few. ↵

- Pateman, Participation and Democratic Theory; Barber, Strong Democracy. ↵

- Bowler and Donovan, “Democracy, Institutions, and Attitudes,” 371–390; Smith and Tolbert, Educated by Initiative. But see Dyck and Lascher, Initiatives Without Engagement; Bernhard, “Does Direct Democracy Increase Civic Virtues?”; Biggers, Morality at the Ballot. ↵

- Radcliff and Shufeldt, “Direct Democracy,” 1405–1423. ↵

- Wike et al., “Representative Democracy”; Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, “11-State Ballot Initiative.” ↵

- Donovan, “Promise and Perils”; Bowler and Donovan, “Enduring Questions.” ↵

- Carter, Chapman, and Comella et al., “Politicians Take Aim”; Ballotpedia, “Difficulty Analysis”; Boldt, “Direct Democracy”; Matsusaka, “Direct Democracy Backsliding?” ↵