6 State Judicial Systems

Nicholas LaRowe

Chapter Summary

In the complicated dual-judicial structure, Americans are governed by two types of courts: the federal and the state. As each chapter on state institutions illustrates, few Americans know about the state judicial system, including the structure, process, and people involved. This chapter opens with a description of the implications of federalism on justice in our nation, then explains the general structure of state courts, trends in policymaking through the judicial branch, and the various ways in which judges come to the bench (appointments, elections, and hybrid processes). The impact of judicial decision-making will be a major focus, as salient issues such as transgender rights and abortion policy are decided in state courts even though they do not attract the same magnitude of attention as the federal court system.

Student Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Identify the functions of the minor trial courts, major trial courts, and production-line-style justice in state government.

- Assess the role that the judicial system plays in state policy.

- Understand the different mechanisms for judges to get to the bench, including partisan and nonpartisan elections, gubernatorial appointments, and the appointment/retention-election process.

- Compare the central components of judicial policymaking (such as needing standing to bring a case, passive judicial decision-making, and special rules of access) to policymaking through the legislative and executive branches.

- Distinguish between common law and statutory law and their applications.

- Analyze the impact of judicial federalism on salient policy issues.

Focus Questions

These questions illustrate the main concepts covered in the chapter and should help guide discussion as well as enable students to critically analyze and apply the material covered.

What are the basic components of a state court system? What role does each court play? What role do specialty/problem-solving courts play?

What are the various ways in which judges can come to the bench to serve in state judicial systems? Which do you feel is most appropriate and why?

What factors influence how judges make their decisions? Which model of decision-making is most persuasive to you?

What role do state courts play in protecting existing rights and recognizing new rights?

Introduction

For many people, June is a month eagerly anticipated. For children, it marks the long-awaited end of the school year. For many couples, forever begins in June as they tie the knot. For Court watchers, June is the month when the Supreme Court hands down its most consequential rulings of the term, and their anticipation is mixed with glee or dread, depending on the case. On June 24, 2022, nearly fifty years after ruling that the Constitution protected a woman’s right to an abortion, the Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization reversed itself and overruled Roe v. Wade.

Source: “A person holding a sign that says never […] again” by Aiden Frazier, “A group of people holding a sign” by Harrison Mitchell, and “Person holding red Stop Abortion Now signage” by Maria Oswalt on Unsplash / Unsplash License.

The decision sent shockwaves through society. Some celebrated; others mourned. Both supporters and opponents of abortion rights knew what came next: a battle at the state level. And it would be as it had been for the previous fifty years: Courts and judges would be in the thick of the action. Between the Roe and Dobbs rulings, state courts interpreted state abortion legislation guided by Supreme Court rulings such as Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. With the Dobbs ruling, abortion case law disappeared. Whether a right to abortion existed, or what abortion restrictions were permissible, was now no longer a federal matter. Judges in twenty-three states were now tasked with applying state constitutions to laws restricting or altogether banning abortion.[1] As of 2024, courts of last resort in twelve states have recognized a right to abortion in their state’s constitution.

As discussed in Chapter 2, an essential part of any description of the American system is that it is federal, with national and state levels of government. That means politics occurs at the state and national levels. Sometimes the issues and actions are clearly either state level or national; other times discussion and debate occur at both levels simultaneously.

More than that, state courts are largely responsible for the major judicial decisions that impact Americans. Many of the federal court cases come from divisions either among states or between the state and federal powers. At the state level, courts play a vital role in the formation of policy. As in Dobbs v. Jackson (2023), differences within states’ interpretations of constitutional limits can dramatically change how we interpret constitutional rights and freedoms. More directly, one of the most significant functions of government is law and order, and much of that responsibility belongs to the state court system.

Courts have long been at the center of national and state politics and policy. During the first half of the twentieth century, as the country nationalized, the Supreme Court played a major role in policy debates over the size and scope of government during the Great Depression and the 1930s. In the 1960s during the civil rights movement, the Supreme Court broadened civil liberties for criminal defendants. But in the 1970s, as the Court (and the country) moved to the right, state courts became a site of significant political action. This judicial federalism[2] describes efforts by civil libertarians to broaden or win new rights in state-level litigation. In cases as various as same-sex marriage, tort law, gerrymandering, transgender rights, and abortion, state courts have been at the center of the action. Though rulings of the Supreme Court garner more attention and affect the entire nation, such cases are relatively rare; most of the action on the policy debates of the day takes place at the state level. Therefore, to understand the American political system, we must understand the court system. I open the chapter with a brief explanation of what the judicial branch does. I then cover the organization of courts, how judges are selected, and how they make the decisions they do. At the end of the chapter, I return to a discussion of judicial federalism, highlighting some contemporary policy fights and how state courts are involved.

What Does the Court System Do?

The judiciary or court system is the branch of government that interprets the laws that govern society and applies them to specific situations. The judiciary has two basic kinds of courts: trial and appellate courts. Trial courts determine matters of legal fact. They are tasked with determining what is true. Appellate courts determine matters of law. Their role is to look at previously decided court cases and assess whether the law was interpreted and applied correctly. Legal systems are organized in a hierarchy. At the bottom are trial courts. Above the trial courts are one or more levels of appellate courts.

Another organizing feature of legal systems is subject matter jurisdiction. In the United States, two primary kinds of law are civil and criminal law. Civil law concerns the rights and duties of individuals and is used to resolve disputes about these rights and duties. Criminal law has to do with punishing those who commit offenses (crimes) against society. Key to understanding a state’s court or legal system is understanding subject matter jurisdiction, hierarchy, and whether a court decides matters of law or fact.

What Is the Structure of State Courts?

The court systems of the fifty states are, to use a cliché, like snowflakes. Although they share significant similarities, no two are exactly alike. Typically, states will have two levels of trial courts: an appellate court, a state high court, and perhaps one or more courts created to handle specific areas of law. However, there is also significant variation. Texas and Oklahoma have two high courts.[3],[4] In New York, the “supreme” court sits below the court of appeals.[5]

If there were such a thing as an average state court system, it would look something like that in Virginia or Indiana. Virginia’s system has four levels: two levels of trial courts, an appellate court, and a state high court. Indiana’s legal system has four levels as well. However, Indiana also has specific courts for tax cases and probate cases and a small claims court for its most populous county, Marion County.

|

Difference |

Civil Law |

Criminal Law |

|

Who are the parties involved? |

Plaintiff vs. defendant |

The people (the government) vs. a defendant |

|

What is the standard of proof? |

Preponderance of evidence |

Beyond a reasonable doubt |

|

Where does the burden of proof rest? |

With the plaintiff |

With the government |

|

What are some examples of each? |

Personal injury, property dispute, contract disputes |

Murder, larceny, arson |

|

What are common penalties? |

Fines, injunctions, community service |

Incarceration, injunctions, fines |

Minor Trial and Limited Jurisdiction Courts

At the lowest level in the legal system are trial courts. Trial courts are courts of “original jurisdiction.” They hear cases first and determine matters of legal fact. The vast majority of people who come into contact with their state court system do so at what is called the “minor” trial court level. Though the variation in state court systems and quality of recordkeeping makes summary claims difficult, Ohio provides a nice example. In 2022, Ohio recorded approximately 2.4 million trial cases; nearly 1.9 million of those cases landed in minor trial courts.[6] Contrary to how trials are depicted in popular culture, the experience at this level more closely resembles a trip to the department of motor vehicles and is sometimes referred to as production-line justice. Given the immense caseload and the low legal stakes, cases are processed quickly and relatively informally.

These courts handle low-stakes cases such as misdemeanors, traffic cases, and small claims civil cases.[7] They also handle preliminary hearings for more serious cases. Decisions of these trial courts can be appealed to trial courts of general jurisdiction and reheard from the beginning, or de novo.[8]

Sometimes included in this level are courts that deal specifically with family, juvenile, and probate cases and are thus called courts of limited jurisdiction. The jurisdiction of minor and limited jurisdiction courts is at the level of either city or county, and they are generally funded by the level of government they serve.

Major Trial Courts

Beyond the seriousness of the case, major trial courts differ from minor trial courts in several ways. Unlike the production-line brand of justice in the minor trial courts, trials at the major level hear felony cases and look more like the trials of the popular imagination. They can involve juries and witnesses, and proceedings are recorded. Appeals from major trial courts go to appellate courts and are not reheard de novo. Appellate courts accept the legal facts as they have been determined by trial courts. They look at the interpretation and application of law and are discussed further in “Intermediate Court of Appeals.”

|

Trial Courts |

Appellate Courts |

|

•One judge •Jury •Lawyers present evidence •Witness testifies before judge/jury •Emphasis is on debating the facts of the case •Most cases begin (and end) in trial courts |

•More than one judge •No jury •Lawyers do not present evidence •Witnesses do not testify •Emphasis is on matters of the law (and process), not rehearing the facts of the case |

Intermediate Courts of Appeal

Appellate courts are courts that have appellate jurisdiction; that is, they review appeals from lower courts. Unlike trial courts, which determine matters of fact, appellate courts hear appeals about the legal process and interpretation of law. Also unlike trial courts, which accept witness testimony and other evidence to determine matters of fact, appellate courts read legal briefs from both parties, listen to oral arguments, and then issue an opinion, or ruling, on the appeal.

Many appellate courts have both mandatory and discretionary jurisdiction; there are some kinds of appeals they must hear and others they may decide to hear or not. Those appeals they must hear are called appeals by right, and those over which the court has discretion are called appeals by permission. States with small populations, such as Wyoming, may have no intermediate appellate court but only a state high court. In other states, like Utah, there is a single appellate court below the state high court, where cases are heard by a small group, or panel (typically three), of judges who hear oral arguments. In larger states, the appellate courts are organized by geographic district. Our largest state, California, has six appellate districts.

Figure 6.4 – How Cases Reach the Supreme Court

Source: Vox. “How does a case get to the Supreme Court.” YouTube, March 28, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KEjgAXxrkXY / Embedded with the Standard YouTube License.

State Courts of Last Resort

In most states, the highest court in the judicial system is called the supreme court. However, the organization and structure of state court systems vary. Texas and Oklahoma have separate high courts, a supreme court (for civil cases), and a court of criminal appeals. Thus, such courts are typically called state high courts or courts of last resort. One of the most important roles they play in their state’s legal system is to provide interpretive guidance on important matters of law or the state constitution. Lower courts are guided by the rulings of state high courts.

These high courts generally have both mandatory and discretionary appellate jurisdiction as well as original jurisdiction over a small number of cases, such as professional disciplinary matters, advisory opinions, and in some states, capital cases. In rare cases (.00036 percent in 2019), if federal law or the US Constitution is implicated, a case can be appealed from a state court of last resort to the United States Supreme Court.[9] Otherwise, rulings in state courts of last resort are the end of the line.

In one instance, such a case had a seismic effect on the criminal justice system. In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Clarence Gideon, holding that the Sixth Amendment’s right to an attorney applied to felony cases in state court systems—where nearly 99 percent of all cases occur.[10] The ruling required retrials or the freeing of thousands of inmates in Florida alone.[11] Since a large majority of criminal defendants are indigent (the Department of Justice estimates that 80 percent cannot afford an attorney) and since access to an attorney was now a constitutional right, states were obligated to provide attorneys to indigent defendants. They typically did so by either hiring attorneys to serve as public defenders or entering into contracts with local law firms to do the job.

Specialty and Problem-Solving Courts

Outside the “mainstream” judicial system in the state are two other kinds of courts that merit discussion: specialty and problem-solving. Such courts are created to help relieve the caseload burden, deal with difficult and technical bodies of law, and pioneer new methods of dealing with persistent social problems.[12]

Specialty courts are created to deal with some specific subject matter. Several states (e.g., Rhode Island and Nebraska) have worker’s compensation courts, and Oklahoma has a tax court. Though such courts have their own rules, litigation in these courts usually resembles that in the mainstream system; the process is adversarial and overseen by a judge.

In problem-solving courts, the goal is diagnosing and solving issues rather than adversarial litigation aimed at determining matters of fact. In jurisdictions with drug courts, for instance, users of illicit drugs are not punished; rather, their addiction is treated and progress is monitored.[13] In juvenile courts, judges may collaborate with social workers and law enforcement to determine the cause of a problem and devise a solution to help a minor child overcome their troubles. In community courts, low-level criminal and civil matters are handled through the paradigm of restorative justice and reconciliation involving community stakeholders rather than state punishment by government officials. Shoplifters, for example, may be required to pay back what they stole and vandals to repair what they damaged.[14]

What Is the History of State Courts?

The American court system resembles the English system, which is not surprising given America’s origin.[15],[16] However, colonial and then early state courts were adapted in several ways to the conditions of American life. In these early years, before separation of powers had developed as a concept, colonial courts played a major role in government: adjudicating cases and performing various administrative functions such as providing for local roads, issuing licenses, and collecting taxes.[17],[18] In Kentucky, the chief official at the county level is a “judge-executive,” one of the last living descendants of the old system.[19]

Shortly after gaining independence, the American reaction against legal and judicial abuses at the hands of English courts meant an increase in the power of supposedly more responsive and democratic state legislatures at the expense of state courts.[20] A particular sore point was the role courts played in debt collection. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, many veterans had not been paid for their service and were also in debt. In one case, popular anger at this state of affairs boiled over into armed intimidation of local judges and courts, temporarily shutting them down.

Source: “Appalachian Trail 2012” by John Hayes on Flickr / CC BY.

After the Civil War, dramatic changes in society, such as urbanization, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of capitalism, required changes to a court system designed to serve a rural nation. New courts were created to handle a rising caseload. And juvenile and small claims courts were created to deal with specific problems arising out of a changing society. The idiosyncratic nature of state systems and their sometimes haphazard adaptations at times produced unwieldy and complex court systems. In some states, courts had overlapping jurisdictions. There was no effective administrative organization, and legal interpretation often varied by judge.[21] Early in the twentieth century, many states underwent court reunification reforms to streamline, standardize, and better administer the judicial branch.

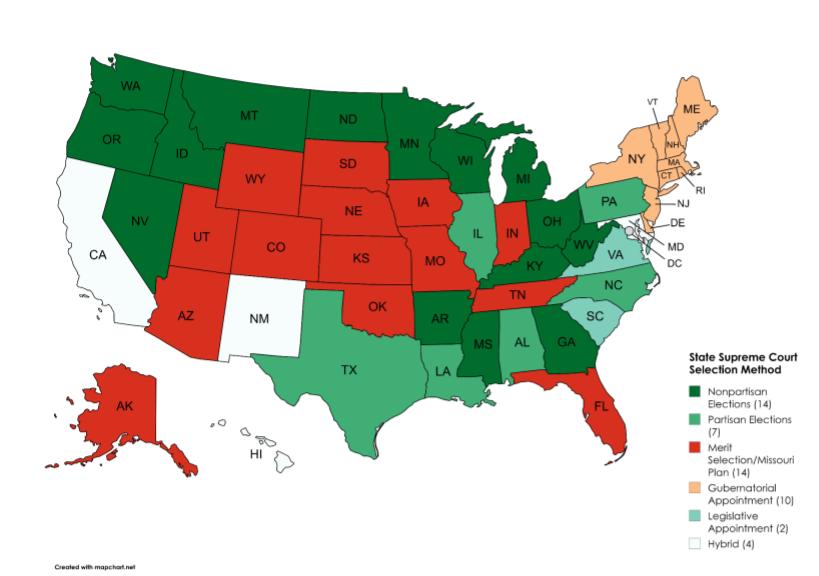

Data Source: Brennan Center for Justice. “Judicial Selection: An Interactive Map.” 2024. https://www.brennancenter.org/judicial-selection-map. Map made by author.

How Are Judges Selected?

Judicial selection reflects two competing values: democratic accountability and judicial impartiality.[22] On the one hand, it seems that judges, like other officials, should be accountable to the people. Yet as interpreters of law, it is important that they do their job impartially, “without fear or favor.” Clearly, these values can be in tension, and the varied models of judicial selection reflect this tension. In some places and at some times, states opted for the accountability promised by judicial elections. At other times, reformers tried to make courts independent, removing politics from the process.

|

Method |

Supreme Court (of 53) |

Court of Appeals (of 45) |

|

Partisan elections |

8 |

9 |

|

Nonpartisan elections |

13 |

16 |

|

Legislative elections |

2 |

4 |

|

Gubernatorial appointment |

5 |

3 |

|

Assisted appointment |

22 |

15 |

|

Combination or other |

1 |

9 |

At the state level, judges come to office generally through one of two methods: elections (partisan or nonpartisan) or appointment (gubernatorial or legislative), with a handful of states using some other plan. In states using appointment, the judges often stand in a retention election after a short period in office. If retained, the judge then sits for a much longer period before subsequent retention elections. Many states employ different processes at different levels; judicial selection in Indiana includes partisan elections, nonpartisan elections, and gubernatorial appointments.

Election

Nearly 90 percent of state court judges come to office via election.[23] Nineteen states hold partisan elections, twenty-one hold nonpartisan elections, and three hold both partisan and nonpartisan elections.[24] In partisan elections, democratic accountability is at its strongest, and these first arose during the Populist Era encompassing President Andrew Jackson’s tenure in office (1829–1837).[25] Such elections have increasingly become indistinguishable from other partisan elections as candidates fundraise, criticize their opponents, and since 2002, are allowed to make policy pledges.[26] Though typically disliked by legal elites, judicial elections are highly popular despite the fact that few people vote in them.[27]

At the turn of the twentieth century, Progressive reformers attempted to make judges more independent of partisan politics. In many states, judicial elections became nonpartisan and candidates ran for office without party labels, leaving voters to make decisions based on factors like name recognition or perceived gender.[28],[29] In many cases, however, partisan influence is not far away. In Michigan, for example, candidates are chosen by political parties but then run in nonpartisan elections.[30] In low-information elections such as these, party identification is a useful cue for confused voters,[31] and candidates often attempt to make their partisan affinity known one way or another.

Appointment

Various appointment plans are another attempt to minimize the political element of judicial selection. Under this heading are several methods of judicial selection, but all share the basic features of candidate nomination and appointment. The most common plan, used in some form by nearly half the states, is the “Missouri” (Missouri was the first adopter in 1940) merit selection plan. As the name suggests, merit selection is a method of choosing judges that attempts to remove politics from judicial selection in favor of simply selecting the best candidate.

The specifics of merit selection vary slightly by state, but the basic outlines of a three-step process are as follows: First, a nominating commission composed of legal elites (judges, lawyers, law professors, and prominent lay members) scrutinizes applicants and recommends candidates. Second, the governor or legislature selects a candidate from the list. Typically, the chosen candidate will sit for a short term, usually one or two years. Third, after this short stint, they stand in a retention election, where voters are asked whether the judge should remain in office. Nearly always victorious, these judges then serve longer terms before the next retention election.[32]

Other Methods

There are simply too many other variations in judicial selection among the states and by the level of court to provide any kind of systematic discussion of selection methods beyond election and standard appointment schemes. It is perhaps best to note again the overwhelming variation and end the section with a few examples: In North Dakota, appellate court judges are selected by state high court justices; in New Hampshire, it is the governor who nominates and an executive council that must approve the nominees. These judges have a rare lifetime appointment, which is limited by a mandatory retirement age of seventy. Delaware requires an even partisan balance on their courts.[33] One could fill an entire book simply delving into the details of judicial selection in the states.

Seeing the variation in judicial selection, a question naturally arises: Which method is best? Those looking for a clear answer are destined to be disappointed. On the one hand, the campaigning involved in judicial elections helps inform the electorate about the candidates for office.[34] Americans tend to view judges more as policymakers than objective legal experts, so the opportunity to choose judges can enhance the perceived legitimacy of the judicial branch. However, campaign contributions reduce the perceptions of legitimacy.[35] Elected judges tend to be more punitive in their sentencing and are less likely to rule in favor of criminal defendants on appeal.[36] Whether this is an argument for or against judicial elections depends on the individual. On the other hand, there is evidence of a racial bias in punitive sentencing, which is a clear drawback of judicial elections.[37] And some research suggests that elected judges produce worse-quality work than appointed judges.[38]

Some had hoped that merit selection would lead to a more diverse and more apolitical judiciary. However, that does not seem to be the case. While merit selection leads to slightly more minority judges, judicial elections have produced more female judges. And as to the claim that merit selection removes politics from the process, critics question whether merit selection removes politics or merely shifts it to the selection of the nominating commission.[39] Even the retention elections used in appointive systems can become contentious, as three Iowa State Supreme Court justices lost their retention elections after they voted to legalize same-sex marriage in 2010.[40]

Thus, if elected judges are more responsive, appointed judges are more impartial. The public overwhelmingly prefers to elect its judges, but appointed judges may be of better quality. And political contention seems inevitable no matter the method of judicial selection. If there is an answer to the question “Which system is best?” it may depend on whether one prioritizes accountability or independence.

How Do Judges Make Decisions?

How judges make it to the bench is an important aspect of state judicial systems. Once they are on the bench, court watchers turn their attention to judicial behavior—how and why judges rule as they do. A significant amount of attention and scholarship[41] focuses on judicial decision-making at the appellate and high court levels, as these decisions guide the legal interpretation and decision-making of lower courts in the legal system. However, the vast majority of cases begin and end at the trial court level, so we begin this section with a discussion of judicial decision-making in trial courts.

In any event, three sets of variables can explain the majority of what goes into judicial decision-making at all levels: judicial policy preferences, legal factors, and the policy preferences of other actors. First, judges have policy views that shape their decisions, whether consciously or unconsciously. Second, statutory and common law, legal reasoning, and case facts shape how a judge decides in a case. Third, in the governmental system of separation of powers, other actors have policy preferences that shape how court rulings are interpreted, applied, complied with (or not), debated, and reformed. The preferences and likely actions of others also shape how judges decide cases. The Supreme Court famously dropped its opposition to the policy initiatives of President Franklin Roosevelt after the popular president threatened to add several members to the Court. Yet these three sets of factors are not exhaustive, and other variables are discussed in “Trial Court Decision-Making” as well.

Trial Court Decision-Making

Trial court decision-making is different from that of appellate courts in several ways. First, judges supervise civil or criminal cases and in many instances must make rulings more or less instantaneously as issues arise during a case. Also, trial judges are the sole deciders on issues, whereas appellate judges typically work in panels of three or more. Furthermore, trial courts have their decision-making shaped by the rulings of state appellate and high courts.

Juries provide a critical function in the judicial process. The US Constitution provides for guarantees to a jury trial (Article III, Section 2), one that is impartial (Sixth Amendment) and available in civil trials (Seventh Amendment). Some courts utilize petite juries, which are smaller in size and are more likely to make efficient decisions, while other courts rely on grand juries, larger in number of members but also more comprehensive. Regardless of the jury size, the scope and mission remain the same: to provide a group of community members serving as a neutral arbitrator of justice.

Despite these differences, decision-making on trial courts is influenced in large part by the same variables as on appellate courts. Trial court decision-making is shaped by the text of the law and the facts at hand. While interpretation and application can vary in nuanced or unclear cases, the law and case facts significantly impact decision-making. Additionally, judges are trained in law school to reason by example, and analogy teaches them to apply underlying legal principles of law (e.g., fairness, equality) in cases where that principle is at play. When applicable, they also use precedent, which is a basic judicial technique to ensure fairness and stability in the application of law to facts. If there is no clear precedent or if there are conflicting precedents, judges may discard this tool.

Van Orden v. Perry (2005) provides an example of legal reasoning, the use of precedent, and how the use and application of precedent can be a matter of dispute—not to mention the federal nature of the system. In this case, a Texas trial court decided that a monument of the Ten Commandments in a public park was not a violation of the First Amendment’s ban on a government “establishment” of religion. On appeal, a majority of the United States Supreme Court agreed, ruling that the display served a “valid secular purpose,” a public acknowledgment of the influence of religion, as they had previously ruled when they permitted a public display of a nativity scene (Lynch v. Donnelly [1984]). However, four of the nine judges disagreed, arguing that the presence of the monument constituted an endorsement of a specific religion, Christianity, and thus was an unconstitutional establishment of religion as they had decided in County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union, Greater Pittsburgh Chapter. Do you think such displays should be allowed, or do they constitute a government establishment of religion?

The policy views of trial judges matter as well. One of the most reliable indicators of how a judge will decide is their party affiliation.[42] In states that hold partisan judicial elections, like Texas, that party affiliation is explicit. In states that hold nonpartisan elections, judges may be affiliated with a party. In states with nonpartisan elections, parties might endorse judicial candidates. Even in states where judges are appointed, there is often a discernible ideological pattern in judicial rulings, consistent with the governor or legislative majority that appointed them.

Beyond legal factors and policy preferences, judges are but single actors in a wider political context. Judges do not enforce their own rulings, so the state legislature, governor, and public opinion shape judicial actions as well.[43] Legislatures can override statutory decisions by passing a law; if necessary, they can initiate amendments if the state constitution is implicated. Governors, as head of the law-enforcing branch, exert significant control over how, and even whether, a ruling is enforced. In many cases, public compliance is necessary for rulings to take effect. Judges are mindful that their political power rests on the respect they are afforded by other actors and hesitate to make rulings that go beyond what others are willing to accept. Even when the ruling came from the Supreme Court, as in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), it led to little desegregation in the Deep South until it was backed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and a supportive president.[44]

Finally, trial court judges often work in the same area where they grew up and were educated. Differences in local political culture can have an impact on decision-making as well. Some jurisdictions are known for particularly lenient or stringent rulings or perhaps are particularly favorable or hostile toward specific cases or parties. For example, the ethnic and religious demographics of Minneapolis and Pittsburgh produced distinct patterns of legal reasoning and decision-making.[45]

How much each set of variables matters is the subject of some dispute among those who study courts. There are generally three models offered to explain judicial decision-making: the legal model, the attitudinal model, and the strategic model.

Legal Model

In this model of judicial decision-making, judges arrive at their conclusions by scrutinizing the plain meaning of the law, the facts of the case, and any relevant precedent. In this paradigm, judges are, as Chief Justice John Roberts argued in his confirmation hearings, “umpires” who simply call balls and strikes.[46]

Although the law, facts, and precedent certainly have some influence on how a case is decided, the legal model is generally criticized as idealized at best and perhaps simplistic and naive.[47] First, the language of the law is not always clear. In such cases, do judges look to legislative intent or consult a dictionary and use the literal meaning of the law, or should judges attempt to apply the basic principles and purposes of the law to the facts before them? Furthermore, in many cases, the facts are equivocal, and reasonable judges could disagree as to which party deserves to win. The same goes for precedent; in many instances, there are enough cases decided so that a judge on either side of a case could find ample precedent to support their decision. Finally, if judges simply look to the law, facts, and precedent, why is it that judges seem to rule on cases in stable and predictable patterns? Such critiques led court scholars (if not judges) to discard the legal model in favor of a more “realistic” theory of judicial decision-making.[48]

Attitudinal Model

The attitudinal model is a parsimonious explanation of judicial behavior, which holds that how a judge rules on a case is simply a function of their policy views. Judges, like any other political actor, have policy views and wish to advance those views. They do so by ruling in predictable ideological patterns on the cases before them. It would not be too much of an exaggeration to describe judges in this model as little legislatures of three, five, seven, or nine members. As court scholars Segal and Spaeth put it, “Rehnquist votes the way he does because he is extremely conservative; Marshall voted the way he did because he is extremely liberal.”[49] There is substantial empirical support for this model. Judges do in fact vote in predictable patterns. This theory is at its strongest when the judges are at the top of the legal hierarchy, in either the state or federal judicial system.[50]

However, the attitudinal model has also come under criticism.[51] The fundamental weakness of the theory is that it is reductionist: While policy views are undoubtedly an important factor, they are not the sole factor in judicial decision-making. There are a number of instances of judges breaking their voting tendencies. In other cases, we see unanimous rulings on courts with established ideological divides. How can an explanation based solely on policy views explain such outcomes?

Strategic Model

A third model of judicial decision-making synthesizes insights from both the legal and attitudinal models and incorporates an additional factor: policy preferences of other relevant actors. In the strategic model, judges hold policy views and wish to advance them. But rather than acting as single-minded partisans, they take into account the policy views of others, which are “constraints” on judges otherwise simply voting their preference on a case. One major conceptual insight of the strategic model is that judges—even state high court justices—are but single actors in a large political context that influences how (and sometimes whether) rulings will be interpreted and applied. These constraints are either internal or external to the court. The internal constraints are the law, case facts, precedent, and views of the other judges.[52] The law may be open to interpretation, but it is not completely malleable. And judges must consider the views of their colleagues on the panel, as they all get to vote. Externally, judges must pay heed to the views of the governor, state legislature, and even public opinion, as discussed earlier.

What Role Do Courts Play in the Policymaking Process?

When people think about government policymaking, what likely comes to mind is lawmaking by the legislature or the governor taking action or issuing an executive order. Or perhaps even administrative agencies passing and enforcing regulations. But as Alexis de Tocqueville observed, “There is almost no political question in the United States that is not resolved sooner or later into a judicial question.”[53] Since the earliest days of the nation, courts have been involved in the contention of politics.

Despite protests by judges that they merely interpret and apply the law, judges are policymakers. This may sound strange, but when judges apply a law to a specific set of facts, they issue a legally binding command or prohibition. If a trial court judge finds funding for local school districts inequitable, a funding increase is required. If a state court of last resort rules that an abortion restriction is permissible, the state is empowered to enforce restrictions. Though judicial policymaking differs in important ways from legislative or executive policymaking, their decisions have the force of law and create winners and losers. In those ways, courts can be considered “political.”[54]

However, courts are also distinct from the more purely political legislative and executive branches. First, they have less control over the issues they do and do not hear. Unlike a legislator or governor, who can pick and choose which issues they want to prioritize, courts are passive decision-makers. They have to wait for others to bring a case or controversy to them. And unlike legislators or governors, courts have less ability to avoid issues they would rather not decide. So long as a case is properly before them, they must act. The requirements are that it must be a “live” (not hypothetical or resolved) dispute, the parties involved must be directly implicated, other avenues of resolution have been exhausted, and the issue is not more appropriately handled by the other branches. These requirements are collectively referred to as the “doctrines of access.”[55] Finally, while those in the legislative and executive branches are free to bring in any moral or political perspective or data or evidence they wish to the policymaking process, in court the process is far more structured regarding how arguments are made, what counts as evidence, and how issues will be decided.

I now return to discussing the role state courts play as policymakers and political actors, in particular since the judicial federalism movement of the 1970s.[56] In addition to the fears of civil libertarians that a more conservative Supreme Court would narrow or reverse past favorable rulings, another reason why policy fights moved to state courts has to do with the content of state constitutions. Many state constitutions contain more rights guarantees than the national Constitution does.[57] In 2016, Indiana joined nearly two dozen other states and adopted a right to hunt and fish.[58] In 2021, Maine added a constitutional right to food.[59] Thus, the rights the national Constitution protects can be thought of as a floor, so litigation of rights claims at the state level held much more potential for policy victories for advocates of various causes.

At the beginning of the era of judicial federalism, the action in state courts was the result of national trends and rulings: The fight to preserve or expand the rights of criminal defendants moved to state courts. In the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, state courts were involved in the debate over same-sex marriage as state judges grappled to apply their state constitutions to the question of whether the right to marry extended to same-sex couples. The last two states admitted to the Union were two of the first states to recognize claims of same-sex couples. In 1993, the Hawaii high court ruled that denying marriage licenses to same-sex couples violated Hawaii’s equal protection clause.[60] In 1998, a superior court judge in Alaska ruled that absent a compelling state interest,[61] same-sex couples had the same fundamental right to marry as did opposite-sex couples.[62] It was only later, in 2015, that the Supreme Court held that marriage was a fundamental right that extended to same-sex couples.[63] As was the case in other issues, the Supreme Court ruling served to ratify an evolving national consensus bubbling up from the states rather than serving as a political trailblazer.[64]

In recent years, state courts increasingly have become the site of debate over an evolving array of questions regarding transgender rights. As of 2024, the Kansas state high court currently is weighing who decides, and on what basis, sex is determined in official state records.[65] In Indiana, judges are grappling with a challenge to a state ban on gender transition treatments for minors.[66] And in Tennessee, courts have fielded a challenge to a state law requiring transgender students participating in school-sponsored athletics to play for a team that matches their sex at birth.[67] However these and other debates play out, state judges and courts will play a significant role in the process.

Conclusion

Though courts are arguably the least understood branch of government, they play a vital role in both the “political” and legal systems of their states.[68] In a country of approximately 340 million people, state courts hear nearly one hundred million cases a year, ranging from family law to traffic tickets to the most serious crimes. Courts are also deeply implicated, whether they wish it or not, in policy debates, including school funding levels, abortion, and gay and transgender rights. Whether in small claims court or in the state court of last resort, judges are a part of the wider sociopolitical context. Some are elected; others are selected. They bring their own policy views and institutional concerns to the table and are keenly aware of the policy preferences of other major political actors. If we are to fully understand the political dynamics and policy outcomes in the fifty different states, understanding how state courts function and what makes judges tick is an essential piece of the puzzle.

Bibliography

Abbe, Owen G., and Paul S. Herrnson. “Public Financing for Judicial Elections? A Judicious Perspective on the ABA’s Proposal for Campaign Finance Reform.” Polity 35, no. 4 (2002): 535–554.

Baehr v. Lewin, 74 Haw. (1993), 530.

Ballotpedia. “Indiana Right to Hunt and Fish, Public Question 1.” 2016. https://ballotpedia.org/Indiana_Right_to_Hunt_and_Fish,_Public_Question_1_(2016).

Belenko, Steven S. “Research on Drug Courts: A Critical Review, 2001 Update.” National Drug Court Institute Review 2 (2002): 1–58.

Bermann, Greg, and John Feinblatt. “Problem-Solving Courts: A Brief Primer.” Law and Policy 23 (2002): 125–140.

Berry, Kate. “How Judicial Elections Impact Criminal Cases.” Brennan Center for Justice, 2015.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Damon M. Cann. “Party Identification and Vote Choice in Partisan and Nonpartisan Elections.” Political Behavior 7, no. 1 (2015): 43–66.

Brause v. Alaska, WL 88743 (1998).

Brennan Center. “Judicial Selection in the States.” 2024. https://www.brennancenter.org/judicial-selection-map.

Brennan Center. “State Court Abortion Litigation Tracker.” December 5, 2023. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/state-court-abortion-litigation-tracker.

Bybee, Keith J. “Legal Realism, Common Courtesy, and Hypocrisy.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 1, no. 1 (February 2005): 76.

Canes-Wrone, Brandice, and Tom S. Clark. “Judicial Independence and Nonpartisan Elections.” Wisconsin Law Review 1 (2009): 21–65.

Carp, Robert A., Ronald Stidham, and Kenneth L. Manning. Judicial Process in America. 8th ed. CQ Press, 2011.

Choi, Stephen J., G. Mitu Gulati, and Eric A. Posner. “Professionals or Politicians: The Uncertain Empirical Case for an Elected Rather Than Appointed Judiciary.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 26, no. 2 (2008): 290–336.

Coltri, Laurie S. Alternative Dispute Resolution: A Conflict Diagnosis Approach. Prentice-Hall, 2009.

Council of State Governments. The Book of the States. 2021. https://bookofthestates.org.

Court Statistics Project. “New York.” n.d. https://www.courtstatistics.org/state-courts/state-court-structures.

Court Statistics Project. “Oklahoma.” n.d. https://www.courtstatistics.org/state-courts/state-court-structures.

Court Statistics Project. “Texas.” n.d. https://www.courtstatistics.org/state-courts/state-court-structures.

Coyle, Marcia. “State Courts, Voters Increasingly Turning to State Constitutions to Protect Rights.” National Constitution Center, 2023. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/state-courts-voters-increasingly-turning-to-state-constitutions-to-protect-rights.

DuBois, Philip. From Ballot to Bench: Judicial Elections and the Quest for Accountability. University of Texas Press, 1980.

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. The Choices Justices Make. CQ Press, 2001.

Friedman, Lawrence M. A History of American Law. 3rd ed. Touchstone, 2005.

Geyh, Charles G. “Why Judicial Elections Stink.” Ohio State Law Journal 43 (2003): 64.

Gibson, James L. Electing Judges: The Surprising Effects of Campaigning on Judicial Legitimacy. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Glick, Henry R., and Kenneth N. Vines. State Court Systems. Prentice-Hall, 1973.

Hall, Melinda G., and Chris W. Bonneau. In Defense of Judicial Elections. Routledge, 2009.

K.C. v. Medical Licensing Board of Indiana (2023).

Kansas v. Harper (2023).

Kentucky Legislative Research Commission. “Fiscal Court.” 1996. County Government in Kentucky: Informational Bulletin No. 115.

Kincaid, J. “New Judicial Federalism.” Journal of State Government 61, no. 5 (September/October 1988): 163–169.

L.E. v. Lee (2023).

Levin, Martin A. Urban Politics and the Criminal Courts. University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Magleby, David B., Paul C. Light, and Christine L. Nemacheck. Government by the People. 24th ed. Pearson, 2014.

Maltzman, Forrest, James F. Spriggs II, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. Crafting Law on the Supreme Court: The Collegial Game. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

McDermott, Monika L. “Voting Cues in Low-Information Elections: Candidate Gender as a Social Information Variable in Contemporary United States Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 1 (1997): 270–83.

Neubauer, David W., and Stehpen S. Meinhold. Judicial Process: Law, Courts, and Politics in the United States. Cengage Learning, 2017.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 US (2015), 644.

Park, Kyung H. “The Impact of Judicial Elections in the Sentencing of Black Crime.” Journal of Human Resources 52, no. 4 (2017): 998–1031.

Rosenberg, Gerald N. The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Harold J. Spaeth. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Segal, J. A., and H. J. Spaeth. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Surrency, Erwin C. “The Courts in the American Colonies.” American Journal of Legal History, 11, no. 3 (1967): 253–276.

Tarr, G. Allen. “State Constitutional Rights Federalism.” Federalism in America: An Encyclopedia. Last updated August 2020. https://encyclopedia.federalism.org/index.php?title=State_Constitutional_Rights_Federalism, also, available under the federal Constitution.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. Edited by Harvey C. Mansfield and Debra Winthrop. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

United States Courts. “Chief Justice Roberts Statement—Nomination Process.” n.d. https://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/chief-justice-roberts-statement-nomination-process.

Watson, Richard A., and Rondal G. Downing. The Politics of Bench and Bar: Judicial Selection Under the Missouri Non-Partisan Court Plan. Wiley and Sons, 1969.

Wheat, Elizabeth, and Mark S. Hurwitz. “The Politics of Judicial Selection: The Case of the Michigan Supreme Court.” Judicature (January/February 2013): 178–188.

- Brennan Center, “State Court Abortion Litigation Tracker.” ↵

- Kincaid, “New Judicial Federalism.” ↵

- Court Statistics Project, “Texas.” ↵

- Court Statistics Project, “Oklahoma.” ↵

- Court Statistics Project, “New York.” ↵

- https://www.courtstatistics.org/court-statistics/interactive-caseload-data-displays/csp-stat-nav-cards-first-row/csp-stat-overview. ↵

- The upper limit to qualify for small claims court ranges from ,500 in Kentucky to ,000 in Tennessee. ↵

- Magleby, Light, and Nemacheck et al., Government by the People. ↵

- https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/09/empirical-scotus-the-importance-of-state-court-cases-before-scotus/. ↵

- https://www.courtstatistics.org/court-statistics/state-versus-federal-caseloads. ↵

- https://www.floridabar.org/the-florida-bar-journal/gideon-v-wainwright-a-40th-birthday-celebration-and-the-threat-of-a-midlife-crisis/. ↵

- Bermann and Feinblatt, “Problem-Solving Courts,” 125–140. ↵

- Belenko, “Research on Drug Courts,” 1–58. ↵

- Coltri, Alternative Dispute Resolution. ↵

- Neubauer and Meinhold,. Judicial Process. ↵

- Forty-nine of fifty states use a common law legal system inherited and adapted from the English system of common law. The exception is Louisiana, which has a hybrid common law and civil law system, reflecting both French and English influence. ↵

- Friedman, History of American Law. ↵

- Surrency, “Courts in the American Colonies,” 253–276. ↵

- Kentucky Legislative Research Commission, “Fiscal Court.” ↵

- Six of the twenty-seven grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence have to do with courts, judges, or trials. ↵

- Glick and Vines, State Court Systems. ↵

- Council of State Governments, Book of the States. ↵

- https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/judicial-selection-21st-century. ↵

- Arizona, Georgia, and Indiana. ↵

- DuBois, From Ballot to Bench. ↵

- Hall and Bonneau, In Defense of Judicial Elections. ↵

- Geyh, “Why Judicial Elections Stink,” 64. ↵

- McDermott, “Voting Cues,” 270–83. ↵

- Canes-Wrone and Clark, “Judicial Independence,” 21–65. ↵

- Wheat and Hurwitz, “Politics of Judicial Selection,” 178–188. ↵

- Bonneau and Cann, “Party Identification,” 43–66. ↵

- Council of State Governments, Book of the States. ↵

- Brennan Center, “Judicial Selection in the States.”; https://www.brennancenter.org/judicial-selection-map. ↵

- Hall and Bonneau, In Defense of Judicial Elections. ↵

- Gibson, Electing Judges. ↵

- Berry, “How Judicial Elections Impact.” ↵

- Park, “Impact of Judicial Elections,” 998–1031. ↵

- Choi et al., “Professionals or Politicians,” 290–336. ↵

- Watson and Downing, Politics of Bench and Bar. ↵

- https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/04/us/politics/04judges.html. ↵

- E.g., Segal and Spaeth, Supreme Court. ↵

- Carp, Stidham, and Manning et al., Judicial Process in America. ↵

- Epstein and Knight, Choices Justices Make. ↵

- Rosenberg, Hollow Hope. ↵

- Levin, Urban Politics and the Criminal Courts. ↵

- United States Courts, “Chief Justice Roberts Statement.” ↵

- Segal and Spaeth, Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. ↵

- Bybee, “Legal Realism,” 76. ↵

- Segal and Spaeth, Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model. ↵

- Segal and Spaeth, Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. ↵

- Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck et al., Crafting Law. ↵

- Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck et al., Crafting Law. ↵

- Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 257. ↵

- Neubauer and Meinhold, Judicial Process. ↵

- Neubauer and Meinhold, Judicial Process. ↵

- Tarr, “State Constitutional Rights Federalism.” ↵

- Tarr, “State Constitutional Rights Federalism.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Indiana Right to Hunt and Fish.” ↵

- Coyle, “State Courts.”; https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/state-courts-voters-increasingly-turning-to-state-constitutions-to-protect-rights. ↵

- Baehr v. Lewin, 74 Haw. (1993), 530. ↵

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/strict_scrutiny. ↵

- Brause v. Alaska WL 88743 (1998). ↵

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 US (2015), 644. ↵

- Rosenberg, Hollow Hope. ↵

- Kansas v. Harper (2023). ↵

- K.C. v. Medical Licensing Board of Indiana (2023). ↵

- L.E. v. Lee (2023). ↵

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1989/06/23/wapner-v-rehnquist-no-contest/3bbbd97f-8c38-4cd0-b24c-dd0290855f86/. ↵