1 An Introduction to State and Local Government

Gregory Shufeldt

Chapter Summary

This chapter provides an introduction to the unique rights and responsibilities of state and local governments. Many students are familiar with the federal government, as they were introduced to it as early as grade school, but they are not used to thinking about state governments, what they do, and how the states can vary (and the ways in which they cannot) from other states. This chapter frames the exciting nature of state and local politics by comparing two competing visions for democratic governance: States serve as laboratories of democracy or laboratories of autocracy. We encourage students to begin to think about both the magnitude of influence state policies have and the range of differences we can see across the fifty states in our nation.

Student Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Explain the difference between politics and political science.

- Identify the role of politics, comparisons, and cultural differences in state governments.

- Understand the role that differences in historical context, economic development, racial/ethnic/religious background, and other cultural components play in the unique identity of a state.

- Assess the value in comparing state governments and local governments, with an emphasis on the impact behavior and institutions have in the resulting policy.

- Analyze why state political comparisons emphasize measurable, objective characteristics.

- Apply state political comparisons to current salient issues, such as K–12 education or election laws.

Focus Questions

These questions illustrate the main concepts covered in the chapter and should help guide discussion as well as enable students to critically analyze and apply the material covered.

Which concept, laboratories of democracy or autocracy, best describes how state and local governments promote democratic governance?

What is the essential difference between political science and politics?

What makes the study of state and local government different from the study of the federal government?

How does the comparative method help political scientists understand and assess differences across state governments?

What Makes the Dynamics of State and Local Government Exciting?

We cannot imagine a more exciting time to study state politics.

If you are predisposed to optimism, state and local governments are able to function and produce public policy in accordance with the majority in more instances much more frequently than the federal government is able to do. If you are predisposed to cynicism (or reality, per some), state and local governments reveal the worst impulses of human nature.

With hints of optimism and pessimism, this is the point of view offered by this textbook. It celebrates the diversity and inclusion—while illuminating the ugliness of prejudice and exclusion—fundamental to the beauty and complexity of being fifty different states under one nation. This tension is not new, and we are not the first to observe it.

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (after which Brandeis University is named) famously remarked, “It is one of the happy accidents of the federal system that a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”[1]

Source: “Brandeis, Louis D. Justice” by Harris & Ewing, photographer / Public Domain.

States have been and continue to be at the vanguard of public policy, a laboratory of democracy. They often serve as the breeding ground for policy experimentation that leads to national changes. As you will read in the following chapters, it was states that gave women and racial minorities the right to vote before the federal government. States sought to legalize same-sex marriage before the federal government intervened in Obergefell v. Hodges. States set a more generous minimum wage than the state floor. States have innovated to reduce the costs of voting by introducing convenience voting measures like vote by mail, early voting, and same-day registration. We have seen states elect women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community to offices high and low.

States innovate and design policies that diffuse to other states or become the framework for federal legislation. For example, current federal policies that govern diverse policy realms like education, health care, and social welfare all started as state plans. Likewise, by requiring balanced budgets, states have been at the forefront of limiting the amount of money the government can collect, requiring the government to be responsible stewards of taxpayers’ money.

Yet at the same time, states are not delivering on the promise of democracy—far from it, as the quality of democracy varies considerably across the fifty states.[2] Better said, they are laboratories of autocracy or “laboratories against democracy.”[3] Whether through the tyranny of the majority that James Madison and the Federalists feared at the founding of the country or through political leaders exploiting and abusing the powers available to them, states also serve as bulwarks to or the antithesis of progress. At one moment in time (and yet again, today) states thought that federal laws were merely suggestions and they could pick and choose which to follow—leading to the ultimate result of secession and the Civil War. It was states that upheld injustices such as Jim Crow laws that ensured segregation under the mantle of “states’ rights” under one-party Democratic rule.[4] This is not a relic of centuries or decades past—today, it is states implementing Jim Crow 2.0, banning books, and imposing a White Christian Nationalist viewpoint of America on an increasingly diverse country.

We encourage you, the readers, not only to think about different states’ approaches to issues and matters of public policy today, to consider which is most fair, just, or equitable, but also to consider how democracy works in each state. In short, to make normative arguments about how you believe government (and state and local governments, specifically) should work. While we anticipate readers will center their reading based on their specific home state, we encourage you to take a broader, comparative lens. Consider how other states approach these challenges to evaluate both the benefits and disadvantages of how states work to address these pressing issues. Each chapter is accompanied by a case study that highlights this conflict between laboratories of democracy and autocracy.

And so we want to properly set the stage for what is to come. You are studying state and local government and politics in an unprecedented era. Never before, including during the Civil War, has the country faced a time when competition between two major parties is intense, ideologically polarized, and national in scope.

Figure 1.2 – Polarization in Congress Explained

Source: Business Insider. “This 60-Second Animation Shows How Divided Congress Has Become over the Last 60 Years.” YouTube, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tEczkhfLwqM / Embedded with the Standard YouTube License.

Nationally, the two parties are very evenly divided, which has made working together the exception, not the rule.[5] Since 1950, the House of Representatives has changed hands seven times (i.e., gone from Republicans controlling the House to Democrats after an election or vice versa). However, four of these instances have happened in the last fifteen years. Likewise, which party controls the US Senate has changed ten times, three of which occurred in the last fifteen years. In November 2024, it was possible for both chambers to flip—but in the opposite direction for the first time in our country’s history—as Democrats had a chance to retake the House of Representatives, while Republicans had a good opportunity to retake the Senate.[6] Ultimately, Republicans won control of both chambers.

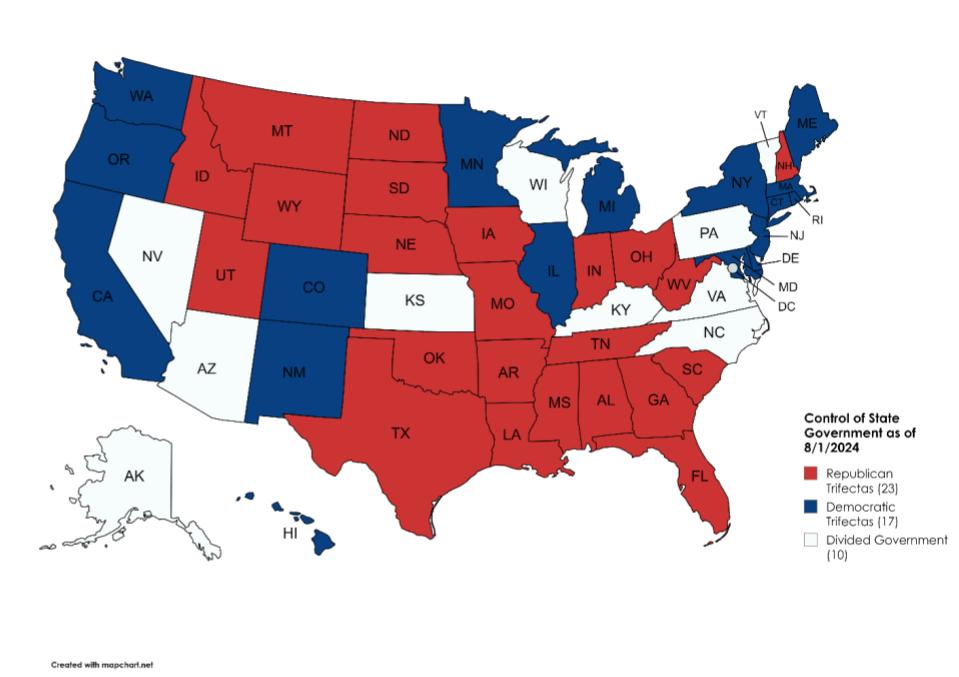

While the two parties are competitive nationally, this competition obscures or masks the general absence of competition at the state and local levels. While control of Congress is tightly contested, this is not the case in individual districts. For example, more than 60 percent of all 435 seats for the House of Representatives now are routinely and safely won by the same party by more than 10 percent (i.e., at least 55 percent to 45 percent).[7] At the state level, the absence of competition is even more stark. More than 82 percent of Americans live in a political trifecta state, where one political party controls both chambers of the state legislature and the governorship. Forty states are currently under one-party control: twenty-three Republican trifectas and seventeen Democratic trifectas.[8]

Data Source: Ballotpedia. “State Government Trifectas.” n.d. Map made by author.

We end this section with a paradox utilizing data from the Pew Research Center. Americans have dismal views toward the federal government:[9]

- 63 percent report having little to no confidence in the future of the US political system.

- 72 percent report that the political system is working either not too well or not at all today.

- 80 percent report feeling angry or frustrated with the federal government.

- 72 percent report unfavorable opinions of Congress.

- 54 percent have an unfavorable view of the Supreme Court.

- 22 percent of Americans trust the federal government to do what is right just about always or most of the time.[10]

- More than 60 percent report negative opinions toward Joe Biden and Donald Trump.[11]

However, Americans report more positive views toward their state and local governments:

- 51 percent report that their state’s governor is doing a good job.

- 73 percent of Republicans think their Republican governor is doing a good job.

- 72 percent of Democrats think their Democratic governor is doing a good job.

- 50 percent have a favorable opinion of their state government.[12]

- 70 percent of Republicans have a favorable opinion of their Republican state government.

- 72 percent of Democrats have a favorable opinion of their Democratic state government.

- 61 percent have a favorable opinion of their local government.

- 63 percent of Republicans and 64 percent of Democrats have favorable opinions of their local government.

Yet here comes the paradox. These mismatched views do not manifest in political knowledge or participation. Americans consistently report higher levels of trust in but lower levels of knowledge of state government than federal government.[13] They report greater feelings of political efficacy, or the belief that the government will listen to them, but lower rates of voting and participation.

Why might that be?

How Do Political Scientists Approach the Study of State Government and Politics?

Politics frequently is defined as “who gets what, when, and how.”[14] In politics, there are winners and losers. We ascribe “right” and “wrong” to different points of view, public policies, and behavior. This is not a politics textbook; this is a textbook for students of political science.

Political science is an academic discipline engaged in the rigorous scientific study of politics and government. It is a social science dedicated to generating knowledge to better understand political thought, behavior, and institutions. Political science in the United States largely is divided into four broad subfields. The two most relevant for our purposes here are comparative politics and American politics. Comparative politics seeks to make comparisons across countries in political behavior and institutions. American politics seeks to examine political behavior and institutions within the United States.

State and local politics is a subfield within American politics. It marries the richness of comparative politics within the context of the United States. Within the American Political Science Association, the professional organization for political scientists, State Politics and Policy is an organized section to connect scholars with this common interest. It hosts an annual conference and produces quarterly issues of State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

While not specific to state politics in the United States, another academic, peer-reviewed journal frequently dedicated to scholarly questions about state politics is Publius: The Journal of Federalism. Federalism is the system of government that we have in the United States where power is divided and shared between the national and state governments.

These two journals are frequent landing spots for state politics research. You will note that articles from both of these outlets appear repeatedly throughout the rest of this textbook. However, the study of state politics is versatile in that it engages in both of the two dominant strands within American politics—political behavior and institutions. As a result, work on American state politics appears in many general political science journals.

It addresses questions regarding political behavior—the political opinions and participation of individuals and groups. This includes political knowledge, public attitudes, political participation, and so on. State politics engages in the study of formal political institutions—the formal branches of government and the rules that govern them. Finally, scholars of state politics also explore mediating institutions—the groups and entities that connect individual political behavior with formal institutions like political parties, interest groups, and the media.

The study of state politics possesses at least two advantages over the broader study of American politics in general. The first is the ability to overcome the “small N” problem. The small sample size associated with the study of national politics and the federal government makes some research questions unanswerable or at least extremely difficult to answer. For example, at any one moment in time, the country has only one president. Famously, this is an N of 1. However, there are fifty governors, which allow political scientists to test hypotheses about the executive branch.

For us, this is what makes the study of state and local government so exciting. We have fifty states and more than ninety thousand government units to utilize to draw conclusions to answer research questions that interest us. Here, Washington, DC, and the fifty states are our unit of analysis, the level that we are utilizing to test our hypothesis.

The second problem the study of state politics is able to overcome is the ability to draw conclusions based on ample variation. In national politics, we do not have the ability to look at a counterfactual. How might the party of the leader of the executive branch affect how they address a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic? Political scientists might be able to draw conclusions between the end of Donald Trump’s presidency and the beginning of Joe Biden’s, but both served as president during very different moments in time that prevent political scientists from truly drawing a one-to-one comparison. There was no variation in March 2020; likewise, there was no variation in March 2021.

In the subsequent chapters, there are some examples of potential questions that cannot be answered to the same extent at the national level compared to the state and local levels.

In Chapter 6, for example, we can explore the relationship between judicial selection methods and the demographic breakdown of the Supreme Court. We cannot truly answer this question at the federal level, since all nine US Supreme Court justices are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. There is no variation. At the state level, however, state supreme court justices are appointed or elected depending on the state. Thus, we have the variation necessary to test a hypothesis about how the selection process impacts the diversity of the bench.

For another example, Chapter 7 will examine how minorities fare in states with direct democracy, where citizens are able to directly vote on public policies. At the federal level, we are unable to test hypotheses about whether minorities (whether in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation, etc.) fare better or worse in representative versus direct democracies. The United States is one of the rare advanced industrial democracies without a process for citizens to vote on a national referendum. At the state level, however, about half of all the states have opportunities for citizens to vote via initiative or referendum.

Each subsequent chapter has a similar type of research question that can only be examined due to the variation and comparability of looking at multiple states. While some scholars of state politics utilize case studies—in-depth examinations of a single geography, political actor, or institution—to draw broader themes and generalizations, this approach is restricted to the same limitation questions faced at the national level. We have only one president at a time, only one party controls the House of Representatives, and so on. If we restrict our analysis to a single state, we lose the ability to make comparisons.

In the study of state politics, political scientists utilize the comparative method. By drawing comparisons across the fifty states, political scientists are better able to understand the relationship between two or more variables. States (state political actors, state political institutions, citizens living within states, etc.) are the units of analysis, the cases used for comparison.

Within the comparative case study method, there are two dominant approaches to identifying the nature of relationships between an independent and dependent variable.[15] Table 1.1 walks through the logic of these two different approaches.

Mill’s Method of Difference (Most Similar)

|

|

Independent Variables |

Dependent Variable |

|

State A |

A B C D E F |

Y |

|

State B |

A B C D E X |

−Y |

|

Since X is the only variable that both State A and State B do not have in common, we can posit that F is associated with or is the cause of Y. |

||

Mill’s Method of Agreement (Most Different)

|

|

Independent Variables |

Dependent Variable |

|

State A |

A B C D E F |

Y |

|

State B |

A V W X Y Z |

Y |

|

Since A is the only variable that both State A and State B have in common, we can posit that A is associated with or is the cause of Y. |

||

But first, a dependent variable is a variable whose value relies on or is contingent on the value of another variable. It “depends.” Some may choose to think of a dependent variable as an outcome or consequence. The value depends on the value of the independent variable. The independent variable is the variable that a researcher either manipulates or does not change. The value is “independent.” While political scientists rarely are comfortable talking in terms of causation, for the purposes of understanding this concept, some may consider dependent variables the “effect.” If a dependent variable is thought of as an effect, then the independent variable is the “cause.” Take for example, state variation in the minimum wage, the dependent variable is a state’s minimum wage, and the independent variables are party control of state government, the presence of the ballot initiative, and the cost of living in each state.

The two dominant approaches were developed by John Stuart Mill. The first approach is called the method of difference, often also called a “most similar” design. Here political scientists would consider two or more states with many similarities (independent variables) but that have different outcomes (dependent variable). By isolating the common variable these states have that is different, researchers would be able to identify this as the likely factor. For example, take Missouri and Indiana. Both are relatively similar in that they are both Midwest states and have comparable costs of living. The Republican Party has enjoyed considerable success controlling both chambers of the state legislature and the governorship. Likewise, the demographics of the two states are similar in many respects. However, Missouri voters are able to collect signatures to put an initiative on the ballot (which they did), while Indiana does not have any form of direct democracy. Therefore, with confidence, we can attribute this policy difference between two similar states to this key variable they do not share.

The second approach from Mill is called the method of agreement, also known as the “most dissimilar” design. In this approach, political scientists would compare states that have considerable differences in most key variables of interest (independent variables) but have the same outcome (dependent variable). By identifying the one or key variable that the states have in common, political scientists can attribute the shared outcome to this variable.

To pick a different policy topic as an example, marijuana legalization is another policy where state variation is tied to the use of the ballot initiative. Missouri has a low cost of living and a Republican-controlled state government. California has the highest cost of living in the country and a Democratic-controlled state government. The one thing (and perhaps one of the few things) these states have in common is that citizens are able to utilize the initiative. In California, voters legalized marijuana in 2016, while Missouri voters did so in 2022.[16]

What’s Next?

Here is how the rest of this textbook is organized.

First, we establish the foundation of state government through the next two substantive chapters. In Chapter 2, federalism, where power is divided and shared between the national and state governments, is explored in more detail. First, the chapter will examine how federalism compares to other systems of government like unitary and confederate models. Then students will learn about how the relationship between states and the federal government has evolved (or devolved) from the time of the Articles of Confederation to today. While the US Constitution provides some broad parameters, much of the nuance for how the levels of government ought to work together is ambiguous and subject to vigorous debate.

Chapter 3 first contrasts the US Constitution with fifty state constitutions. By relying on a constitution, the government is restricted in some ways compared to countries without any formal limits. Given the variations in state constitutions, the power of self-government looks different within a federal system for citizens of each state. While there are significant similarities between the two levels, state constitutions vary in considerable ways and have been revised repeatedly over the nearly 250-year history of the United States.

Next, the textbook shifts its focus to political institutions. Chapter 4 addresses state legislatures. While the legislative branches at the federal level and state legislatures have many similar structures, the diversity across fifty state capitols provides leverage and opportunities to examine a host of features. For example, states vary in the size of their legislative chambers, whether state legislators are subject to term limits, and the length of their terms in general. Utilizing 7,500 state legislators compared to only 535 members of Congress (435 Representatives + 100 Senators) makes drawing conclusions about how the people’s branch can better resemble the people more meaningful.

In Chapter 5, we turn our attention to the state executive branch with a particular emphasis on governors. States vary in which statewide executive positions are elected and the roles and responsibilities of each office. The powers of the governor vary considerably—with some having a significant amount of autonomy and playing a significant role in the legislative process, while others are more limited in scope.

Next, Chapter 6 engages the last of the three branches of government, the judicial branch. Given the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson to overturn nearly fifty years of precedent since Roe v. Wade protected a woman’s right to an abortion, state courts have had their hands full unpacking this new legal framework. While the Supreme Court receives the vast majority of public (and scholarly) attention, most criminal and civil cases start and end within the state judicial system. As such, this chapter helps highlight state variation in how judges are selected and make decisions across the fifty states.

Chapter 7 describes an institutional feature available in slightly more than half of the states. Direct democratic institutions, such as the initiative, the referendum, and recall elections, provide voters with a more hands-on opportunity to influence government compared to the institutions solely available to a representative democracy. As such, this chapter provides a modern opportunity to relitigate many of the debates that shaped the founding of the country. How can democratic institutions promote majority rule while upholding minority rights? This chapter plays a vital role as a point of transition between the other formal political institutions and citizen engagement and the mediating institutions that connect citizens with their government.

In Chapter 8, we identify the various types of and opportunities for political participation. While voting is the most common form of political participation, it lags in state and local elections. This chapter examines how states facilitate and hinder voter participation through the different ways elections are administered across the fifty states. Chapter 9 extends these themes by adding how campaigns—whether from the perspective of the candidate, political party, or voter themselves—experience the different ways elections are conducted at the state and local levels.

In Chapters 10 and 11, we turn our focus to mediating institutions. In Chapter 10, we first explore the role of political parties. More than 82 percent of all Americans currently live in a state where one party dominates, possessing a trifecta where a single party controls both branches of the state legislature and the governorship.[17] In part, political parties now lack much of the local flavor or character that aptly described them for much of our country’s history. Most states are now broadly considered to be “red” states or “blue” states, with little in between.

In Chapter 11, our attention turns to interest groups and the media. Interest groups play an interesting role in state government, where they can provide citizens an opportunity to level the playing field but simultaneously produce inequitable outcomes by allowing those with more—whether it be money, influence, or information—to dictate the outcomes for everyone. Likewise, the media has the potential to serve as an advocate and watchdog for voters—but also plays a role in further polarizing many Americans into opposing camps of us versus them.

Finally, in Chapter 12, we conclude by turning our attention inward toward local governments. In the United States, there are more than ninety thousand different levels of government. Many of them are local; whether it be counties, municipalities, or school boards, these bodies of government play a preeminent role in the life of every American—even though they receive the least amount of attention and voter participation.

Bibliography

Abramowitz, A. “Redistricting and Competition in Congressional Elections.” The Center for Politics, 2022. https://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/redistricting-and-competition-in-congressional-elections/.

Ballotpedia. “Marijuana Laws and Ballot Measures in the United States.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Marijuana_laws_and_ballot_measures_in_the_United_States.

Ballotpedia. “State Government Trifectas.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/State_government_trifectas.

Ballotpedia. “Tennessee General Assembly.” n.d. https://ballotpedia.org/Tennessee_General_Assembly.

Beauchamp, Z. “A Study Confirms It: Tennessee’s Democracy Really Is as Bad as the Expulsions Made You Think.” Vox, 2023. https://www.vox.com/policy/2023/4/7/23673998/tennessee-expulsions-state-democracy-measure.

Bryan, F. Real Democracy: The New England Town Meeting and How It Works. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Conlan, T. “Federal, State, or Local? Trends in the Public’s Judgment.” The Public Perspective 4 (1993): 3–10.

Copeland, J. “Americans Rate Their Federal, State, and Local Governments Less Positively Than a Few Years Ago.” Pew Research Center, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/11/americans-rate-their-federal-state-and-local-governments-less-positively-than-a-few-years-ago/.

Fishkin, J., and D. E. Pozen. “Asymmetrical Constitutional Hardball.” Columbia Law Review 118 (2018): 915–982.

Flavin, P., and G. Shufeldt. “Citizens’ Perceptions of the Quality of Democracy in the American States.” Social Science Quarterly 105 (2024): 817–831.

Flavin, P., and G. Shufeldt. “Comparing Two Measures of Electoral Integrity in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 19 (2019): 83–100.

Flavin, P., and G. Shufeldt. “State Pride and the Quality of Democracy in the American States.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 54 (2024): 386–406.

Foa, R. S., and Y. Mounk. “The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect.” Journal of Democracy 27 (2016): 5–17.

Gelman, A. “About That Bogus Claim That North Carolina Is No Longer a Democracy…” Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science, 2017. https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2017/01/02/bogus-north-korea/.

Gracia, S., and J. Copeland. “Biden, Trump Are Least-Liked Pair of Major Party Presidential Candidates in at Least 3 Decades.” Pew Research Center, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/06/14/biden-trump-are-least-liked-pair-of-major-party-presidential-candidates-in-at-least-3-decades/.

Grumbach, J. Laboratories Against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics. Princeton University Press, 2022.

Hill, K. Democracy in the Fifty States. University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Huq, A., and T. Ginsburg. “How to Lose a Constitutional Democracy.” UCLA Law Review 65 (2018): 80–169.

Kane, P. “House, Senate Elections Are Being Fought on Very Different Political Terrain.” The Washington Post, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/04/06/congressional-elections-house-senate-majority/.

Key, V. Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knopf, 1949.

Lasswell, H. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How. McGraw Hill, 1936.

Lee, F. Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. Broadway Books, 2018.

Lyons, J., W. Jaeger, and J. Wolak. “The Roots of Citizens’ Knowledge of State Politics.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 13 (2012): 183–202.

Matthews, D. “Political Scientist: North Carolina ‘Can No Longer Be Classified as a Full Democracy.’” Vox, 2016. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/12/27/14078646/north-carolina-political-science-democracy.

Mill, J. S. A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. University of Toronto Press, 1843.

New State Ice Co. v. Liebman, 285 US 262 (1932).

Pepper, D. Laboratories of Autocracy: A Wake-Up Call from Behind the Lines. St. Helena Press, 2021.

Perry, N., and L. Rathke. “In Vermont, ‘Town Meeting’ Is Democracy Embodied. What Can the Rest of the Country Learn from It?” Associated Press, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/democracy-town-meeting-vermont-elections-civility-elmore-11d7d1b63037d054506e77e261aff87c.

Pew Charitable Trusts. “Elections Performance Index: Methodology.” 2016. http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2016/08/epi_methodology.pdf.

Pew Research Center. “Americans’ Dismal Views of the Nation’s Politics.” 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/09/19/americans-dismal-views-of-the-nations-politics/.

Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2024.” 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/.

Reynolds, A. “North Carolina Is No Longer Classified as a Democracy.” The News & Observer, 2016. https://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/op-ed/article122593759.html.

Rogers, S. “What Americans Know About Statehouse Democracy.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 23 (2023): 420–442.

Rosen, J. “Americans Don’t Know Much About State Government, Survey Finds.” Johns Hopkins University, 2018. https://hub.jhu.edu/2018/12/14/americans-dont-understand-state-government/.

Varol, O. “Stealth Authoritarianism.” Iowa Law Review 100 (2015): 1673–1742.

Vinson, R. “The Birthplace of American Democracy.” William & Mary, 2019. https://www.wm.edu/sites/1619/news/the-birthplace-of-american-democracy1.pdf.

Waldner, D., and E. Lust. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 29 (2018): 93–113.

Wolak, J. “Why Do People Trust Their State Government?” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 20 (2020): 313–329.

Wolak, J., and C. Palus. “The Dynamics of Public Confidence in U.S. State and Local Government.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 10 (2010): 421–445.

Zhou, L. “The Tennessee Legislature’s Expulsion of Two Black Democrats Is Unprecedented and Undemocratic.” Vox, 2023. https://www.vox.com/politics/2023/4/5/23671339/tennessee-justin-jones-republicans-legislature-expel-democrats.

Zimmerman, J. The New England Town Meeting: Democracy in Action. Praeger, 1999.

Zuckerman, M. “Mirage of Democracy: The Town Meeting in America.” Journal of Public Deliberation 15 (2019): Article 3.

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebman, 285 US 262 (1932). ↵

- Hill, Democracy in the Fifty States. ↵

- Pepper, Laboratories of Autocracy; Grumbach, Laboratories Against Democracy. ↵

- Key, Southern Politics. ↵

- Lee, Insecure Majorities. ↵

- Kane, “House, Senate Elections.” ↵

- Abramowitz, “Redistricting and Competition.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “State Government Trifectas.” ↵

- Pew Research Center, “Americans’ Dismal Views of the Nation’s Politics.” ↵

- Pew Research Center, “Public Trust in Government.” ↵

- Gracia and Copeland, “Biden, Trump Are Least-Liked.” ↵

- Copeland, “Americans Rate Their Federal.” ↵

- Conlan, “Federal, State, or Local?”; Lyons, Jaeger, and Wolak et al., “Roots of Citizens’ Knowledge”; Wolak and Palus, “Dynamics of Public Confidence”; Rosen, “Americans Don’t Know”; Wolak, “Why Do People Trust”; Rogers, “What Americans Know.” ↵

- Lasswell, Politics. ↵

- Mill, System of Logic. ↵

- Ballotpedia, “Marijuana Laws and Ballot Measures.” ↵

- Ballotpedia, “State Government Trifectas.” ↵