2 Cultural Considerations in Online Learning

Chapter Overview

In chapter two, faculty take a deeper dive into the specific challenges international students face in online learning environments. This chapter provides faculty with cultural dimension frameworks to help them identify how various cultural factors can impact learning in online classes.

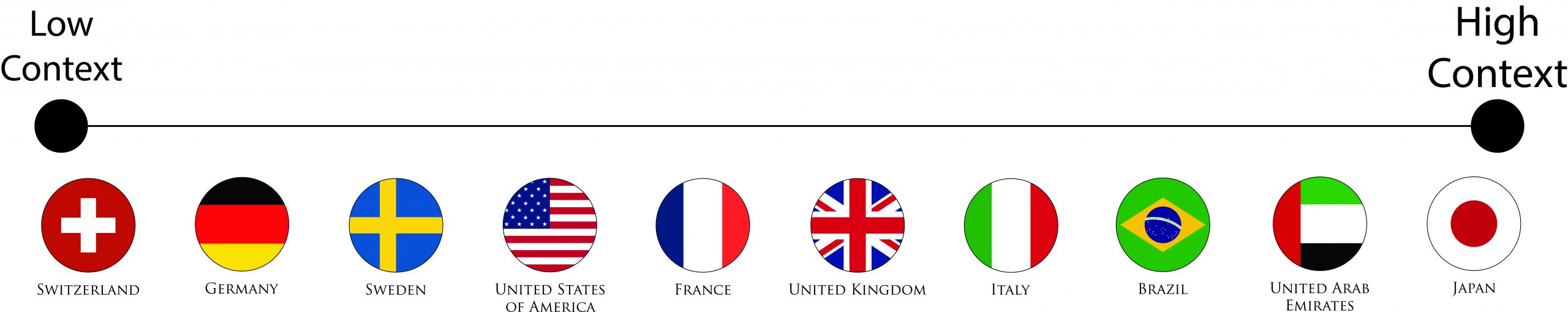

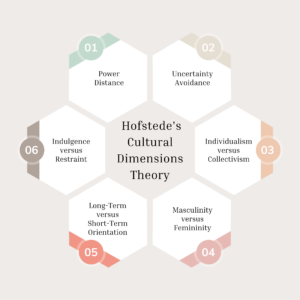

Geert Hofstede’s (2011) proposes a Cultural Dimensions Theory with six dimensions that influence cultural variations: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, long-term versus short-term orientation, and indulgence versus restraint. These dimensions significantly impact educational settings. For instance, instructors in Western cultures are less likely to assume a dominant role, favoring learner-centered approaches (Sadykova & Meskill, 2019).

These educational differences can cause stress for learners adapting to a new culture while balancing their own cultural preferences (Chen et al., 2008). The consideration of how learners from diverse cultures will adapt to potentially unfamiliar education systems is essential to the success and satisfaction of the international student population.

Green et al. (2022) break down Hofstede’s 6 Dimensions into more detail. Let’s explore them.

Your Cultural Identity

Now that you have a better understanding of the cultural considerations we as educators should recognize when teaching diverse student populations, it is time for some self-reflection. By better understanding your own cultural identity, you will be better prepared to recognize the different cultural identities of your students. This will allow you to be more open-minded and aware of their unique challenges when taking online courses in the United States, a culture different from their own.

To help you reflect, here are some questions for you to consider.

- How comfortable are you questioning authority figures (instructors) in a classroom?

- Do you feel your primary loyalty is to yourself and your immediate family, or to a broader group like your community?

- When working on a project, do you value competition and assertiveness, or cooperation and building relationships?

- How comfortable are you with ambiguity and uncertainty in new situations?

- How much emphasis is placed on nonverbal cues like gestures and facial expressions in your culture to convey meaning?

- How will you continue to learn about different cultures throughout your teaching career?

- Consider a time when you experienced a misunderstanding with a student or an academic integrity issue. How might what you have learned in this chapter allow you to view the situation differently?

Attributions

This chapter, Cultural Considerations in Online Learning, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Keirsten Eberts.

This material is adapted from Understanding Cultural Differences by Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, and Darcy Lease-Gubrud, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

This material is adapted from Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions by L. D. Worthy, Trisha Lavigne, & Fernando Romerod, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

References

- Campbell, A. (2017, December 20). Cultural Differences in Plagiarism. Turnitin. https://www.turnitin.com/blog/cultural-differences-in-plagiarism

- Chen, R. T., Bennett, S., & Maton, K. (2008). The adaptation of Chinese international students to online flexible learning: two case studies. Distance Education, 29(3), 307–323. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1080/01587910802395821

- Hayes, N., & Introna, L. D. (2005). Cultural values, plagiarism, and fairness: When plagiarism gets in the way of learning. Ethics & Behavior, 15(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1503_2

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Kumi-Yeboah, A. (2018). Designing a cross-cultural collaborative online learning framework for online instructors. Online Learning, 22(4), 181-201. doi:10.24059/olj.v22i4.1520

- Liu, X., Liu, S., Lee, S., & Magjuka, R. J. (2010). Cultural differences in online learning: international student perceptions. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 13(3), 177–188.

- Sadykova, G., & Meskill, C. (2019). Interculturality in online learning: Instructor and student accommodations. Online Learning Journal, 23(1), 5–21. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.24059/olj.v23i1.1418

- Wang, C., & Reeves, T. (2007). Synchronous online learning experiences: the perspectives of international students from Taiwan. Educational Media International, 44(4), 339–356. https://doi-org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/10.1080/09523980701680821