8 Leveraging Data Visualization to Communicate Across Gaps

One of the criticisms I’ve faced over the years is that I’m not aggressive enough or assertive enough or maybe somehow, because I’m empathetic, it means I’m weak. I totally rebel against that. I refuse to believe that you cannot be both compassionate and strong.

—Jacinda Ardern, prime minister of New Zealand

What Do You Think?

Emilee just joined the conference session entitled A Trio of Perspectives in Data Visualization. She was surprised when the presenter announced that the first task was to join her assigned team based on a preconference survey. As Emilee found her team, the conference presenter gave them additional instructions—to share how their organizations publish information about diversity, equity, and inclusion along with other related issues.

Emilee joined her assigned teammates, Barbara and Tonya. After introducing herself, she discovered that Barbara works at a multinational corporation with a diverse workforce spanning multiple continents. Barbara, beaming with pride, said, “My organization creates visually stunning dashboards showcasing our diversity metrics to represent a comprehensive snapshot of my organization’s demographics to especially highlight and promote gender and ethnic diversity.” As Barbara opens her laptop to share the website, Tonya offers, “I’m not sure I’m in the right team! I’m in sports.”

Tonya works for a sports consulting corporation where she works with different organizations to increase their fan base by reaching diverse cultures, generations, and gender. Tonya offered, “The world of sports faces unique challenges in conveying their commitment to diversity and inclusion. They request specific data visualizations that convey unity and empowerment. I do my best work where I can feature individual stories and collective triumphs.”

Emilee looks at Barbara’s laptop and compliments the aesthetics of her organization’s dashboard. Emilee feels somewhat intimidated. Taking a breath, she says, “I work for a nonprofit and we operate on a shoestring budget. We rely on simple impactful visuals that convey the lived experiences of the communities we serve. We don’t have a metric of our organization; in fact, we only have 12 employees. Instead, our metric is based on the number of clients we help. Most of our clients are from marginalized groups. We provide free-legal counsel.”

Barbara looks perplexed and asks, “What kind of cases?”

Emilee is quick to respond, “Well things like gender pay gap, diversity issues, and inclusion issues. We use minimalist, community-centric visuals. Nothing as fancy as Barbara’s organization!”

Discussion: What do you think?

Introduction

In the era of an increasingly interconnected world, diversity reigns as both a challenge and an opportunity. Effective communication bridges the gaps among diverse populations to foster collaboration, understanding, and progress. Hiring a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) officer can be a significant step for any organization, but thinking about the scenario in the “What Do You Think?” section, how would a nonprofit that has 12 employees justify this action?

One topic DEI officers address is the gender wage gap. According to Elise Gould at the Economic Policy Institute, the gender wage gap in the United States still persists across all levels (low, middle, and high income) and women are paid less than men at every education level (2024). In 2023, “women were paid 21.8% less on average than men in 2023, after controlling for race and ethnicity, education, age, and geographic division” (Gouse, 2024, para. 1). It’s an even bleaker picture if you dive into the data on Black and Hispanic women.

At its core, this chapter focuses on communication for diverse audiences. Topics to consider for diverse populations include gender, culture, generation, equity, and inclusion. This chapter includes DEI best practices including people-first labeling, purposeful order labels, consideration of missing groups, awareness of stereotyping, and mindful use of icons and shapes. It also includes leadership and communication strategies in relation to the relative burnout that marginalized populations are facing.

As you embark on this journey, it is imperative to recognize that effective communication is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. It requires an understanding of audience dynamics, cultural nuances, and cognitive biases. It is hoped that this chapter will equip you to harness the power of data visualizations as a catalyst for change, driving meaningful dialogue, and fostering a more inclusive society.

Chapter 8 addresses the following learning objectives.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- LO 1: Share strategies that address gender communication issues.

- LO 2: Identify competing ways to influence within the global organization.

- LO 3: Share strategies that address multigenerational communication issues.

- LO 4: Identify data visualization techniques and strategies to address gender, cultural, and multigenerational issues.

- LO 5: Identify how poor visualizations impact diversity, equity, and inclusion.

- LO 6: Apply leadership strategies when your team is burned out (especially from virtual meetings).

- LO 7: Demonstrate best practices of communication for Global Leaders.

Key Terms: Audience and audience perceptions, Brain dominance, Cognitive preference, Conflict, credibility, gender tendencies, gender motivation theory, global leader communication, interruptions, motivation, nonverbal cues, PechaKucha, PESTLE, power through character strengths, presentation designs, remote engagement, remote presenting, SWOT

8.1 Gender Communication Issues

The hope is that laying out what we understand about essential differences in the minds of men and women may lead to greater acceptance and respect of differences.

—Simon Baren-Cohen

Gender communication issues are a complex phenomenon that reaches various aspects of society, from workforce dynamics to decades of gender disparity and stereotyping. To begin, let’s look at gender tendencies. Gender tendencies refer to a pattern or inclination commonly associated with a particular gender based on social norms, cultural expectations, and stereotypes. Examples of gender tendencies include (a) communication style, (b) occupational choices, (c) emotional expression, and (d) leadership style. A critical examination of gender tendencies can help challenge stereotypes and foster a greater understanding of inclusivity across diverse gender identities. It is important to note that gender tendencies are not a fixed characteristic of individuals; instead, they are socially constructed and can vary across different cultures and contexts.

So What Are Gender Tendencies?

Before we start, we must deal with an important caveat. The communication expectations are based on the tendencies of men and women as a group. Individuals may exhibit any combination of “male” and “female” behaviors. For example, when I am in a meeting, I tend to nest and take up a lot of room. I have my laptop and iPad, my notebook always turned to a new blank page, a few mechanical pencils, a couple of pens, and always a cup of coffee. Women normally take less room at a conference table, even pulling in their elbows. Not me. I’m crowding my neighbors and that is a typical male tendency. So let’s look at these male and female tendencies to understand the environment and the audience. Remember, understanding your environment and your audience is the first step to successful communication.

Let’s start with a comparison of tendencies: According to Winstok et al. (2018), “according to gender motivation theory, men are driven by a desire to enhance their status; whereas women are motivated by a desire to reduce risk” (p. 276). Leonard, Beauvais, and Scholls (1999) introduced sources of motivation from three attributes: traits (“repeated behavioral patterns”), competencies (“skills, abilities, talents, knowledge”), and values (“beliefs about desirable outcomes”) (pp. 974–975). Just as one has a dominant hand (either left-handed or right-handed), individuals have a dominant source of motivation. But how did we develop these tendencies through motivation and conflict? And what does that have to do with communication?

Gender Tendency #1–Motivation and Conflict

Male: Childhood games taught him that competition is fun, winning is good, performing aggressively is acceptable, and boasting of your success is normal (Shaffer, D. & Kipp, K., 2013). And these social cues learned in childhood are the foundation of why a male views conflict as impersonal. He may even consider conflict a necessary part of a working relationship!

Female: Childhood games taught her to compromise and collaborate. She competes primarily with herself and tends to be modest about accomplishments. She is motivated by connections and causes. She takes conflict personally (Doyle, 2022).

In a study by Eagly et al. (1994) the Miner Sentence Completion Scale (MSCS) showed that men scored higher than women on competitive games, competitive situations, assertive roles, imposing issues and standing out from the group. Women scored higher on authority figures and routine administrative functions. It is no surprise that male managers are often perceived as autocratic leaders. However, a newer study, using the same MSCS, discovered there was no significant difference between men and women for “competitive situations” or “standing out in a group” (Thorton et al., 1997).

The most common workforce conflicts include employment conditions, supervisor decisions, personality conflicts, and uncivil behavior. According to Van Gramberg et al. (2020), only 21% of conflicts are fully resolved. No wonder organizations are experiencing high turnover!

As an aside, conflict resolution in the workplace must start with both parties recognizing that a problem exists with the intent of reaching a mutual agreement. Changes in attitudes or behaviors can lessen negative feelings. However, understanding what triggers the episodes of conflict can often lead to someone saying, “I didn’t know that bothered you.” Using “active listening” is a communication technique for conflict resolution. It requires the listener to restate or paraphrase what they just heard to confirm their understanding. Instead of mentally preparing a response, listen to points being made (Chastain, 2013)!

What Data Visualization Strategies Help With Communicating?

Effective data visualization strategies that cater to different genders should aim to be inclusive, engaging, and relatable. Let’s look through some of these strategies.

- Use gender-neutral language, imagery, and color. Create data visualizations that use language and imagery that are inclusive and gender neutral. Avoid stereotypes. If you know you have a diverse audience, opt for visuals and language that resonates with all members of the audience.

- Example #1: Avoid using pink for girls and blue for boys as part of the color palette.

- Example #2: In a survey, several participants did not answer the gender question (male or female). As a visualization designer, do not introduce the gender synthetically. Instead, just indicate “identity not listed” instead of “other.” To most, other feels like a catchall category.

- Balance visuals and textual information to tell a story: Strive for a balance between visual elements and textual annotations in your data visualizations. Provide clear, concise explanations alongside visual representations to ensure comprehension.

- Example #1: Use people-first language. So “people with disabilities” or “communities of color.”

![]() Shonk, K. (2024, April 18). Conflict Styles and Bargaining Styles. Daily Blog—Program on Negotiation—Harvard Law School. https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/conflict-resolution/conflict-styles-and-bargaining-styles/

Shonk, K. (2024, April 18). Conflict Styles and Bargaining Styles. Daily Blog—Program on Negotiation—Harvard Law School. https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/conflict-resolution/conflict-styles-and-bargaining-styles/

![]() Kahane, A. (2017). Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don’t Agree with or Like or Trust. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Kahane, A. (2017). Collaborating with the Enemy: How to Work with People You Don’t Agree with or Like or Trust. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Gender Tendency #2—“I” Versus “We”

Male: Males have traditionally been afforded attention-getting roles and have no trouble using the word I. According to Sarah Carmichael (2014) in The Perils of Self-Promotion, a routine use of “I did this” or “I did that” is a symptom of self-promotion. And this tendency is tied to what males typically value: power, ability, and achievement. Carmichael shares, “People do not value confidence unless it is accompanied by competence” (para 8).

Female: Females have traditionally been afforded attention-giving roles attached to an affiliation or the wider needs of a corporate community. She uses the word we. She is impressed by personal transparency and professional courage.

Teddy Roosevelt was often teased at his overuse of “I.” In fact, the “New York World put a running score on its front page that year at 563,877,207 to record the number of times Roosevelt used ‘I’ in his public addresses” (Dalton, 2007, p. 361). TR was quite the character; we especially enjoyed his attempt to legislate a change in the spelling of 300 words. He failed then, but now we use them (check instead of cheque, or color instead of colour, etc.).

Currently, most leadership programs talk about the use of “We” instead of “me.” A Harvard Business Review article, “If You Want to be the Boss, Say ‘We’ Not ‘I,’” has some relevant insight. Changing to “we” language can help “shift your perspective from self-focused to others-focused, make you more aware of the needs of others . . . [and] make you a better leader” (Burkus, D., 2015, para. 8). It is worth fighting the tendency to say “I” if you wish to lead a team!

What Examples of Using “We” Can Help With Data Storytelling?

- Use inclusive framing through shared goals and experiences using “we/us” to emphasize common goals and a common purpose.

- Example #1: Use phrases like “Together, we can address this challenge.”

- Use collaboration techniques. Engage the audience to contribute problem-solving strategies.

- Example #1: Use phrasing like, “Let’s work together to find innovative solutions to this problem.”

- Share power techniques. Empowerment grows exponentially when you build your narrative around shared values and aspirations.

- Example #1: Use phrasing like, “Together, we have the power to make a difference in our communities.”

- Example #2: When you need the audience to share responsibility and accountability and to take ownership of the issue, you can use phrasing like, “It’s up to all of us to ensure we . . .”

Gender Tendency #3—Cognitive Preference Instead of Brain Dominance

Male: Early literature associated males with left-brain orientation, which “produces problem-solving skills that are logical, analytical, factual, and hierarchical” (American Management Association International Presentation Skills Workshop, 2015, p. 131).

Females: Early literature associated females with right-brain orientation, which “produces problem-solving skills that are creative, sensitive, and nonhierarchical” (American Management Association International Presentation Skills Workshop, 2015, p. 132).

Females are great creative problem-solvers, but you find this same ability in males. A study conducted by Hardy & Gibson discovered that there was a gender difference in the approach to problem-solving in two of four samples, so the results are somewhat inconclusive. However, this same study indicated, “on average, females were found to produce higher quality creative problem solutions in all four samples” (Hardy & Gibson, 2015, p. 101). Creative problem-solving is defined as the production of elegant solutions in response to complex, novel, and ill-defined problems (Hardy & Gibson, 2015).

The dialogue surrounding left-brain versus right-brain orientation has taken place over the last decade. It’s almost like comparing left-handed and right-handed people. Over 85% of the population is right-handed. Which hand you use does not cause much of an impact (except the early stigma several decades ago where children were forced to write with their right hand). Mostly, you hear about left-handed people when you watch baseball (or bowling!). So the left-brain versus right-brain arguments sound familiar. That’s why the “whole brain thinking” introduced by Herrmann is so interesting.

According to the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument, a four-quadrant model of cognitive preferences is more applicable. Herrmann’s theory was for either gender to develop “whole brain thinking” to lead to creative problem-solving (Faust, 2019, para. 20). The quadrant reminds us of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), and you can find research that makes a comparison. But for now, let’s look at the Herrmann model. As you review Table 8.1 keep in mind that this is a framework for understanding cognitive preferences. Each person’s brain operates across these dimensions and individual strengths can exceed specific quadrants. According to LEADx, the organization that carries on the work of Herrmann, the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument helps you determine your dominance in how you think. But even more interesting is the ability to recognize your team’s quadrants.

Table 8.1: Four Quadrants of Brain Dominance

|

Quadrant |

Keywords to describe |

Preferred Activities |

|

Quadrant A—Left cerebral hemisphere—analytical |

Logical, factual, critical, technical, and quantitative. |

Collecting data, listening to informational lectures, reading textbooks. Judging ideas based on facts, criteria and logical reasoning. |

|

Quadrant B—Left limbic system—sequential |

Conservative, structured, organized, detailed, and planned |

Following directions, repetitive detailed problems, time management and schedules. Known as organizers. |

|

Quadrant C—Right limbic system—interpersonal |

Kinesthetic, emotional, spiritual, sensory, feeling |

Listening to and sharing ideas, looking for personal meaning, sensory input, and group study. Sometimes called humanitarians. |

|

Quadrant D-Right cerebral hemisphere—imaginative |

Visual, holistic, intuitive, innovative, and conceptual |

Looking at the big picture, taking initiative, simulations (what if questions), visual aids. Appreciate the beauty of a problem, brainstorming. Innovators fall in this category. |

What Examples of Leveraging Our Understanding of Brain Dominance Can Help With Data Storytelling?

- When presenting: Make sure you provide data visualizations or narrative that resonates with each quadrant.

- Example #1: Quadrant A will want to see facts. Quadrant B will want to see an organized approach, Quadrant C will want to see the value of solving the issue, Quadrant D will want to see how the solution fits in the big picture.

![]() A great resource for “whole brain thinking” can be found at the Herrmann website. Essentially, the free resources “help decode and harness your cognitive diversity to achieve better management results” (Herrmann, 2020). Link: https://www.thinkherrmann.com/resources. Link to Herrmann Example Report

A great resource for “whole brain thinking” can be found at the Herrmann website. Essentially, the free resources “help decode and harness your cognitive diversity to achieve better management results” (Herrmann, 2020). Link: https://www.thinkherrmann.com/resources. Link to Herrmann Example Report

As you can tell from Table 8.1, you don’t see gender in the mix, but you may recognize the quadrant you resonate with just by looking at the preferred activities. Let’s look at nonverbal cues next.

Gender Tendency #4—Nonverbal Cues

Male: Males are likely to hear your literal words and miss your underlying emotion or see your nonverbal cues. He is “not likely to express his feelings through facial expressions” (American Management Association International Presentation Skills Workshop, 2015, p. 131).

Female: Females are very proficient at decoding nonverbal meaning and “nonverbal messages carry over four times the weight of verbal messages” (National Alliance for Partnerships in Equity, 2020, p. 2). Additionally, females are likely to display feelings through facial expression or body language. But males are likely to miss it!

As an aside, in most “two-person conversations, nonverbal messages convey more than 65% of meaning” (National Alliance for Partnerships in Equity, 2020, p. 2). That’s no surprise when you realize our “faces can demonstrate more than 10,000 facial expressions!” (Point Park University—Online, 2017).

Even more interesting is the 7-38-55 rule by Mehrabian, Wiener, & Ferris (1967) that shared this formula but with some caution. The rule states that 7% of meaning is communicated through spoken word, 38% through tone of voice, and 55% through body language. The authors urge caution because the formula does not apply to every situation. Note that 55% is nonverbal! Even the way you stand can have an influence on your audience and impact you as well.

For example, because someone crosses their arms over their chest doesn’t always mean they are closed to your presentation; it may just mean they are cold!

Just remember, nonverbal cues can contradict or negate verbal messages. An interaction where words say one thing and nonverbal cues say another is called a double message, and everyone finds this confusing.

What Examples of Leveraging Our Understanding of Our Audience and Looking for Nonverbal Cues Can Help With Data Storytelling?

- When presenting: Make sure you pay particular attention to your nonverbal cues.

- Example #1: If you stand with your hands clasped down low in front of you, it may look like you are trying to make yourself small. Audiences won’t react to that as well (Weiss, 2015).

- Example #2: Know your audience. In the book Presentation Skills: Educate, Inspire, and Engage Your Audience (2015), Michael Weiss points out four personalities that should influence how you present (pp. 46–56). These four personalities are the Driver, the Amiable, the Analytical, and the Expressive, and each type has preferences in how you present to them.

- Presenting to the Driver: Use brief, short-term options, and keep things focused on the present. Let the driver take control if they request it. The best data visualization is a dashboard to provide options, which should be up to date. Nonverbal cues of the Driver include leaning forward, putting elbows on the table, and giving a firm handshake.

- Presenting to the Amiable: The presentation should be traditional and inclusive of the entire team. Personal sharing is OK; the Amiable appreciates a safe, comfortable environment and doesn’t like to feel rushed or confronted. They will get back to you. If Drivers are in the same room, emphasize “This is a safe environment.” Nonverbal cues of the Amiable include palms open and welcoming, great eye contact, and animated hands, face, and eyes.

- Presenting to the Analytical: The Analytical wants all data (past, present, and future). They are detail oriented, want to see the plan, need time to verify data analysis, and have an obsession with being right. Nonverbal cues of the Analytical include the following: sits up very straight, is somewhat rigid but tends to lean back, and gives limited eye contact.

- Presenting to the Expressive: The Expressive wants to hear how the story will end. Painting a picture with your narrative will engage the Expressive. The Expressive wants to be asked what they think, appreciates compliments, and feels comfortable and engaged if they can contribute their ideas and tell their stories. Nonverbal cues of the Expressive include leaning forward to make eye contact and being animated in posture (restless).

If you are interested in learning more about presenting, please feel free to read this book by Michael Weiss. It is especially helpful if you struggle with getting nervous before a presentation!

Weiss, M. (2015). Presentation Skills: Educate, Inspire, and Engage Your Audience. Business Expert Press. ProQuest EBook Central Database.

NAPE. (2023). Gender Communication Quiz. National Alliance for Partnerships in Equity. https://napequity.org/pipe-training/r1e-gender-communications-quiz/

Gender Tendency #5—Interruptions

Male: Males are more likely to interrupt women than interrupt other men and they mean nothing personal by the interruption. “According to world-renowned gender communication expert Deborah Tannen, men speak to determine and achieve power and status. Women talk to determine and achieve connection” (Ibarra, Tannen, Williams, & Hewlett, 2019, p. 80).

Given that in American society speaking is perceived as a power position, it is no wonder that men interrupt to take the floor more often. “In using conversation to enhance connection, women are much less likely to interrupt, as it is seen as disrespectful” (Shore, 2017, p. 37)

Female: Females are less likely to interrupt men, but when females are interrupted by men, they tend to take it personally.

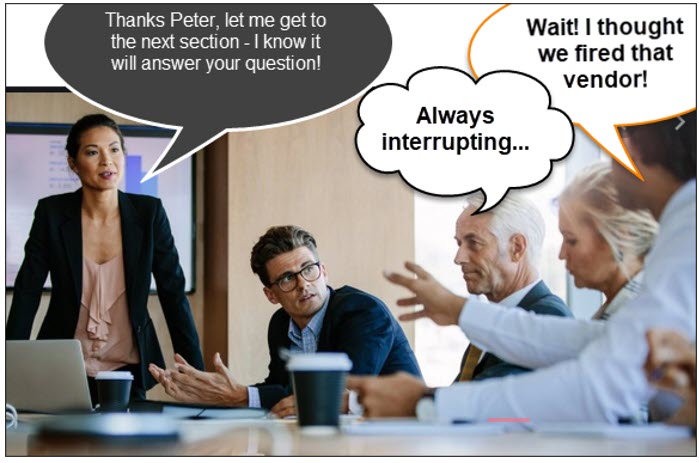

Figure 8.1—Interruptions and How to Handle It

What Strategies Can We Use When a Presentation Gets Interrupted?

- When your presentation is interrupted, determine the reason first.

- Example #1—Is the interruption for clarity? There are strategies for deflecting interruptions (for any reason other than clarity). For example, you can ask, “There are a few more essential points I’d like to make. Can you delay a moment?”

- Example #2—Is the interruption because they want to support your position? This can happen when men feel motivated to support based on your language and word choice. Instead of words like “believe,” use “know” or instead of “might” use “will.” (Shore, 2017, p. 37) and don’t use phrases like “I just” or “I think” because these phrases limit your authority and conviction.

- Another strategy is to notice body language. When you see men lean away or look away from you, they may be ready to interrupt, so “look them in the eye, lean in and take yourself seriously if you want to be heard” (Shore, 2017, p. 35).

Reflective listening: If you face interruptions from your team, ask your team to practice a version of “reflective listening.” “Anyone interrupting repeats or paraphrases what the speaker was saying and then explains the connection to the new thought. This prompts teams to be more aware of when and who they’re interrupting. This won’t work for every meeting because it slows the pace, though it is a good exercise to default to when excessive interruptions re-emerge” (Dotter, 2019, para 5).

Gender Tendency #6—Defining a Problem and Situation

Male: Men tend to define a situation in terms of outcome. Males will assume that your presentation of a problem (even a hypothetical problem used for illustration) is a direct request for a solution.

Female: Females tend to define the same issue in terms of the people affected by it. Other females will respond to your presentation of a problem with support and reassurance with a willingness to collaborate, to share experiences, and to jointly discuss solutions. “Successful collaboration requires a cooperative spirit and mutual respect” (Doyle, Careers, 2020, para. 15). A good collaborator can analyze the problem without assigning blame and women are better at this than men.

These observations highlight the different perspectives. While men lean toward analytical solutions, women often consider the human aspect. These tendencies are generalizations and don’t apply to all. Individual variations exist; expect a blend.

What Strategies Can We Use When Presenting a Problem to a Mixed Audience?

- When you present to a mixed audience, plan to appeal to both genders.

- Example #1—If you are presenting to a mixed audience, what can you do? The strategy is to define the problem in a manner that appeals to both genders. Defining the problem is key—paint the picture, show the impact, the consequences, and the emotions the problem is creating for those involved (Cooper, 2014). You already consider the decision-makers in your audience; this is just considering the additional issues based on “gender.”

-

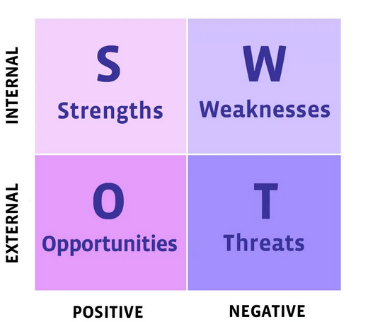

- Example #2—Use analytical tools like PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental) or SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) so males can focus on the specific industry competition in related industries or organizations. Be direct and show results-oriented impact on the organization’s bottom line. These tools were demonstrated in previous chapters.

-

- Example #3—Share the most important information first. One of our favorite quotes made in Storytelling With Data is “If you only had a limited amount of time or a single sentence to tell your audience what they need to know, what would you say?” (Knaflic, 2015, p. 39).

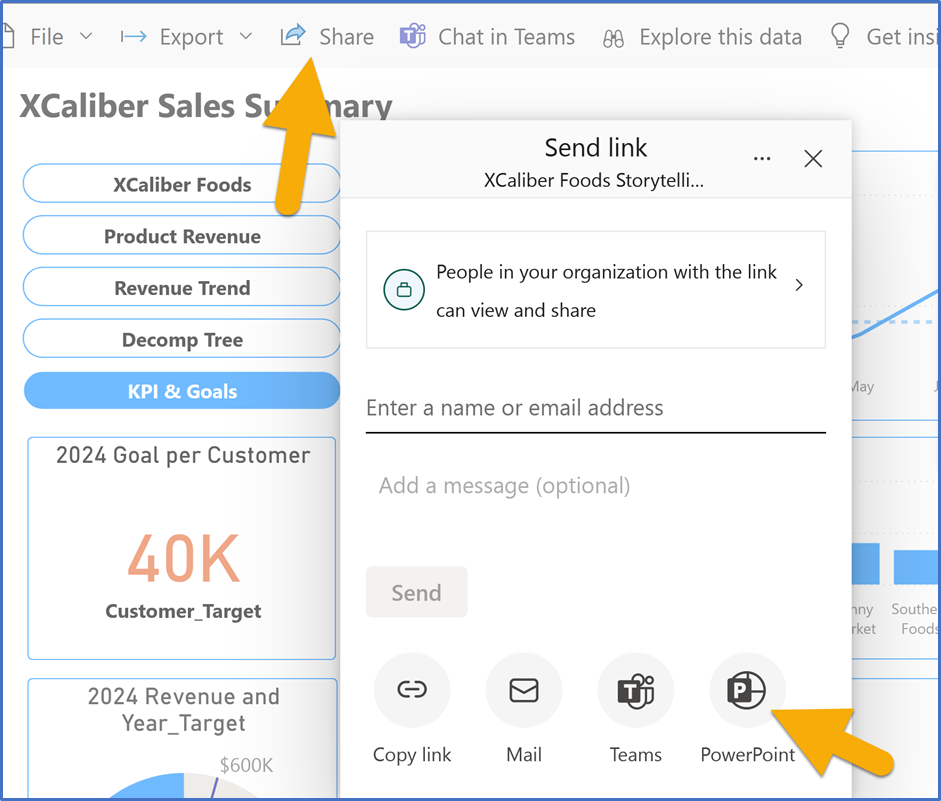

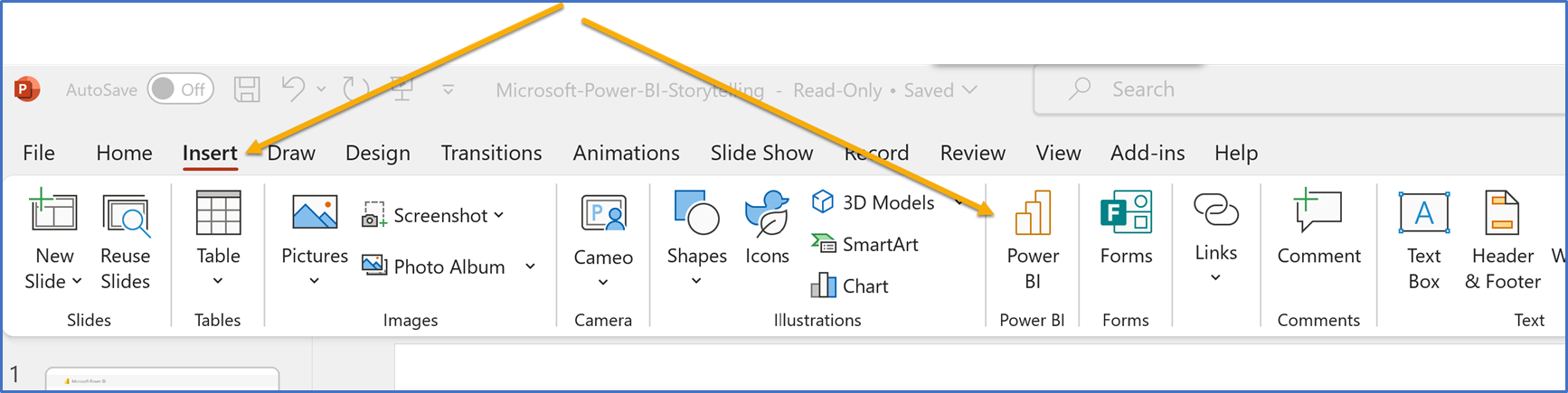

Note: Author Illustration (2025) - Example #4—Most presenters use PowerPoint but if you want to show an interactive report from PowerPoint, make sure to install the Power BI add-in in PowerPoint. Let’s look at the step-by-step section to see how this might be used.

- Example #3—Share the most important information first. One of our favorite quotes made in Storytelling With Data is “If you only had a limited amount of time or a single sentence to tell your audience what they need to know, what would you say?” (Knaflic, 2015, p. 39).

Step-by-Step to Bring Power BI Into PowerPoint

Step-by-Step to Bring Power BI Into PowerPoint

Screenshots of PowerPoint Interface © Microsoft Corporation. Author Annotations Added.

This application would be for fairly sophisticated audiences where your audience might be asking questions and asking for on-the-spot analysis.

Step 1—Open Power BI Services (Online)

Step 2—Open a report found in My Workspace. I opened XCaliber Foods Storytelling-Draft 2.

Step 3—Click the share button and choose PowerPoint as you see in Figure 8.2.

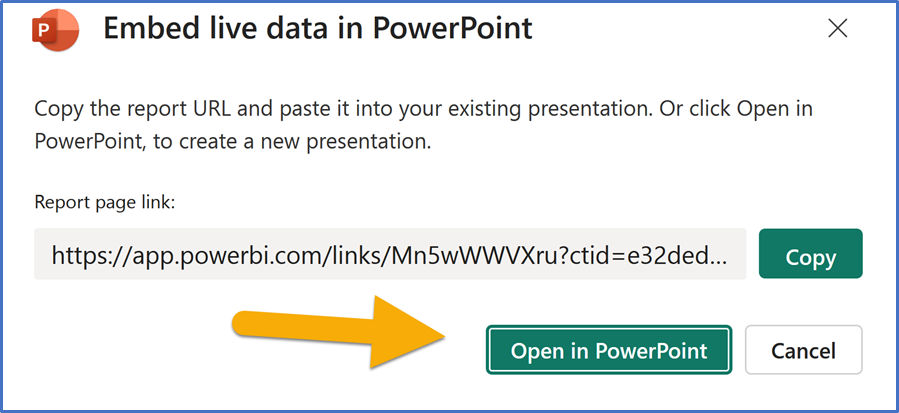

Step 4—When you see the pop-up (Figure 8.3), choose Open in PowerPoint

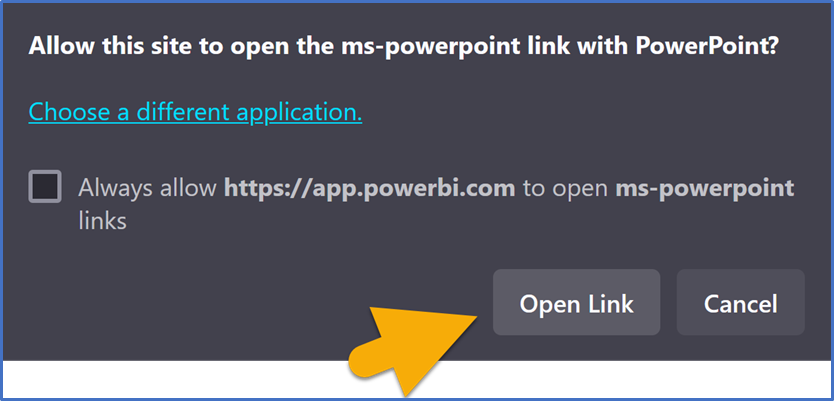

Step 5—In the next pop-up, choose open the link (Figure 8.4) so PowerPoint will connect to it.

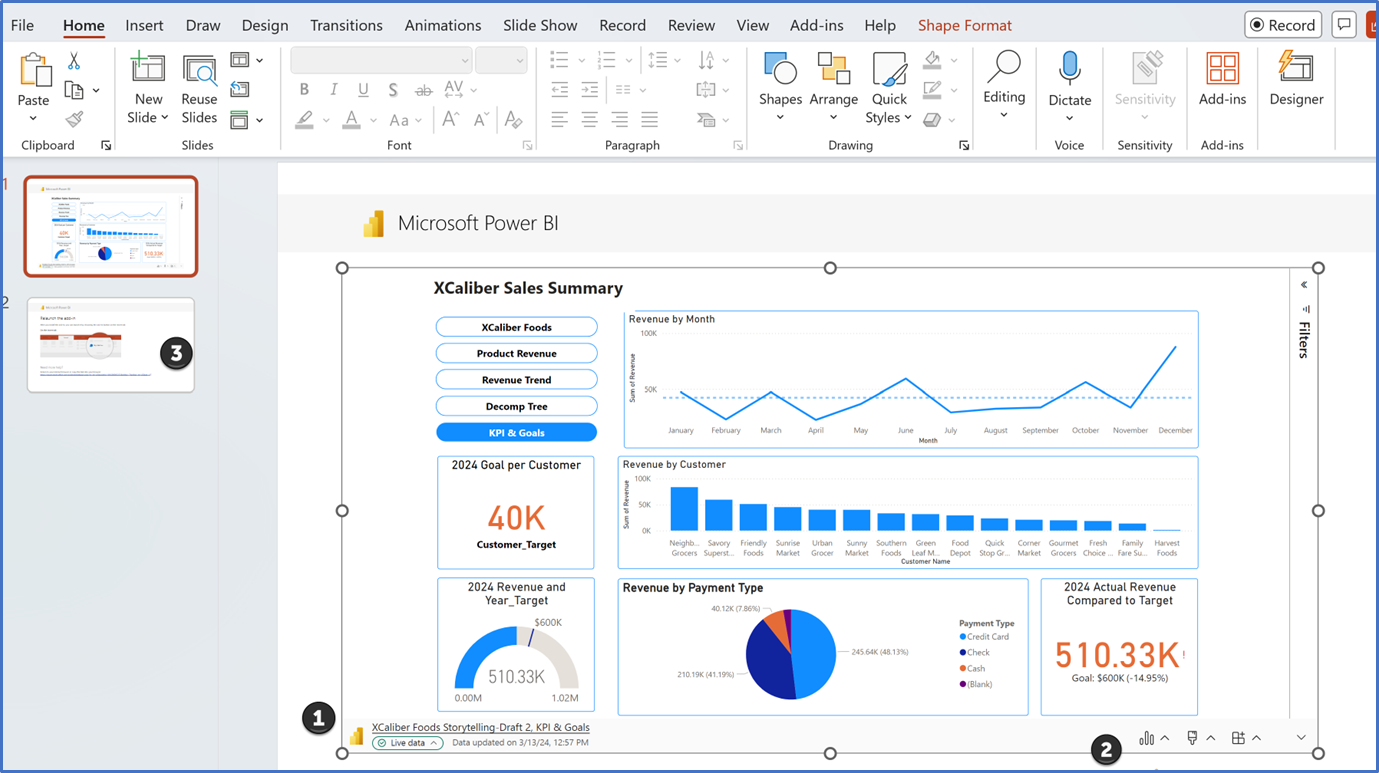

Step 6—Customize the Power BI Report in PowerPoint as shown in Figure 8.5.

![]() In this step, please note the information on the lower left (Live data) of the PowerPoint (see Figure 8.5). It should identify the name of the Power BI Report (in this case XCaliber Foods Storytelling—Draft 2, KPI & Goals), along with the date updated.

In this step, please note the information on the lower left (Live data) of the PowerPoint (see Figure 8.5). It should identify the name of the Power BI Report (in this case XCaliber Foods Storytelling—Draft 2, KPI & Goals), along with the date updated.

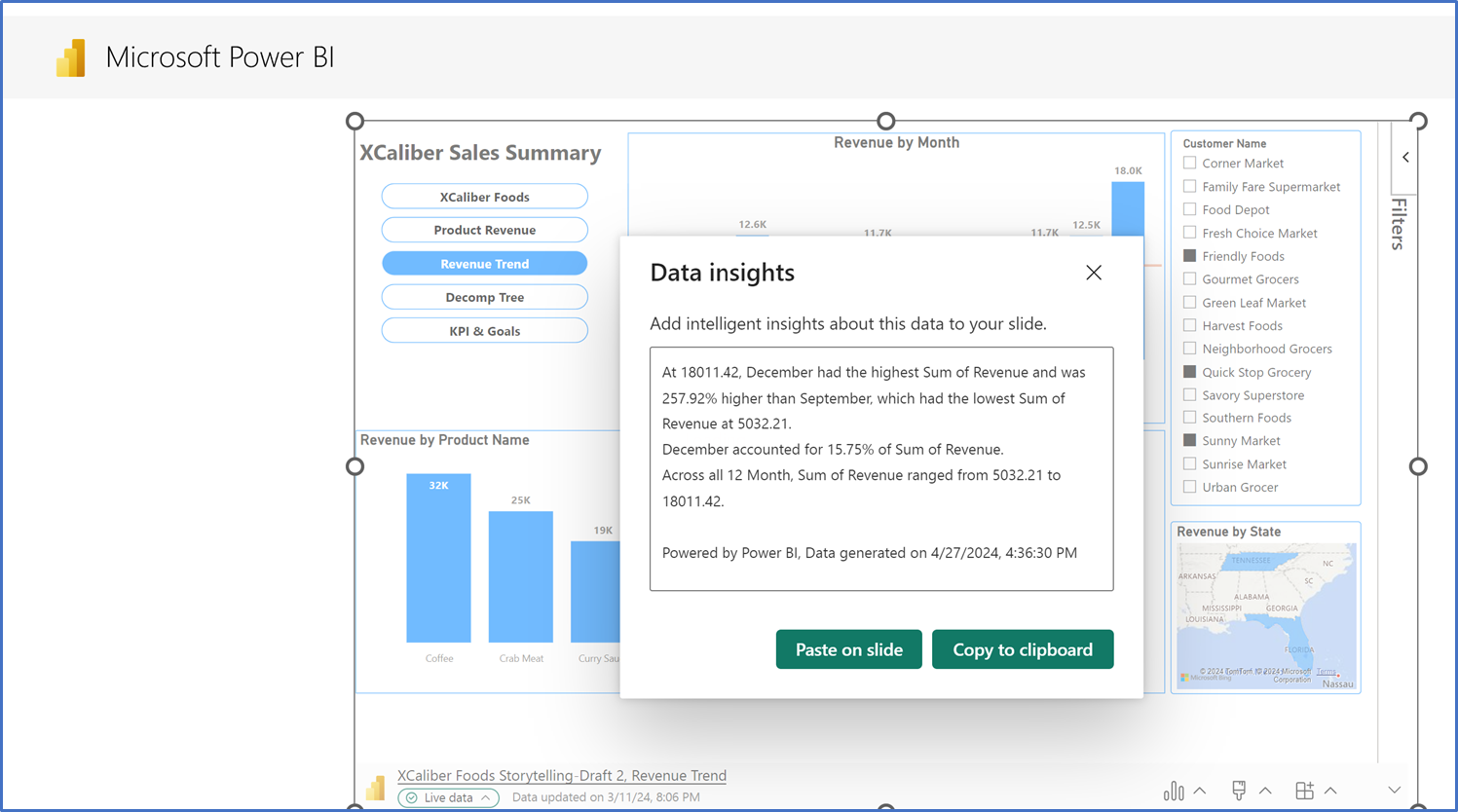

![]() In the lower right of PowerPoint, you will notice several icons. The first icon looks like a three-column chart. When you click on it, you see the options filter, data insights, refresh, and reset, as shown in Figure 8.6[1]. Data Insights is like what you would expect from Power BI. If you have trouble loading Data Insights, troubleshoot the Power BI add-in for PowerPoint. In Figure 8.6, we demonstrate the data insight feature by using the Revenue Trend section of the report. Notice, you can paste on a slide or copy to the clipboard.

In the lower right of PowerPoint, you will notice several icons. The first icon looks like a three-column chart. When you click on it, you see the options filter, data insights, refresh, and reset, as shown in Figure 8.6[1]. Data Insights is like what you would expect from Power BI. If you have trouble loading Data Insights, troubleshoot the Power BI add-in for PowerPoint. In Figure 8.6, we demonstrate the data insight feature by using the Revenue Trend section of the report. Notice, you can paste on a slide or copy to the clipboard.

The second icon in the lower right allows you to add style to your Power BI Report—you can add an outline. The last icon allows you to clear data, set slide show settings, and Learn.

![]() When you share the report to PowerPoint, it creates two slides—one that is from XCaliber Foods, but the other is an instruction about using the add-in feature in PowerPoint to launch the report. The Power BI button shows up on the ribbon.

When you share the report to PowerPoint, it creates two slides—one that is from XCaliber Foods, but the other is an instruction about using the add-in feature in PowerPoint to launch the report. The Power BI button shows up on the ribbon.

![]() Recall your best and your worst presentation. What strategies would you apply to your worst presentation?

Recall your best and your worst presentation. What strategies would you apply to your worst presentation?

8.1 Self-Assessment: Gender Communication Issues

Learning Objective #1—Share strategies that address gender communication issues

![]()

8.1 Exercise 1: What Do You Think?

Learning Objective #1—Share strategies that address gender communication issues

Learning Objective #5—Identify how poor visualizations impact diversity, equity, and inclusion

Instructions: Go to the “What Do You Think?” section at the beginning of the chapter and answer the following questions.

Instructions: Go to the “What Do You Think?” section at the beginning of the chapter and answer the following questions.

- Compare and contrast the three organizations in leveraging data visualizations to promote diversity, inclusion, gender equity, and so on. What are the common themes that emerge and what unique insights can each organization offer?

- How does the context of sports influence the effectiveness of data visualization in promoting diversity and inclusion? Are there unique opportunities or limitations inherent in this domain compared to the corporate and nonprofit sectors?

- Consider the role of leadership in shaping the narrative around diversity and inclusion. How might the leadership styles be different?

- Is one approach more effective than another?

- Reflect on your own experiences with data visualization. Have you encountered a visualization that resonated deeply, and how did it contribute to your understanding of a particular issue?

Post to the discussion board, or be prepared to discuss in class.

8.2 Cultural Communication Issues

Different does not mean deficient, it simply means different.

—Tatiana Kolovou, teaching professor of management

Making Sense of Cultural Differences in a Communicative World

The rapid rise of global business, combined with the challenges brought on by the pandemic, has made cross-cultural considerations and planning an urgent priority for even the most indifferent organizational communicators. During the difficult days of the pandemic, nearly the entire world was forced to remote work, requiring immediate connection with colleagues across various parts of the globe. In Upwork’s Future Workforce Survey, 1,000 U.S. hiring managers were asked, “Has responding to the pandemic forced you to make changes to the following management practice areas that will stay with you in the long-run?” (Ozimek, 2021, para. 15). The survey results indicated over 60% changed management practices for team meetings (structure and cadence) and over 55% indicated changed management practices for employee/internal communication.

At any given moment, countless individuals are connecting instantly with their organization’s global offices. This shift has brought together a diverse array of cross-cultural communicators, who collaborate virtually to solve problems, present proposals, and engage in meaningful exchanges through numerous virtual platforms. Despite this reality, not all participants have received training on the nuances of cross-cultural communication.

This section seeks to address that gap by discussing key considerations for effectively engaging with diverse audiences and making compelling pitches in our increasingly globalized communication landscape.

Cultural Context Matters

Each culture presents differences, and as highlighted in the quote at the start of this section, these differences should be celebrated for the diversity they bring rather than viewed as deficiencies. Culture encompasses the customs, arts, social institutions, and traditions of a particular nation, people, or other social group. Extensive research has been conducted on the differences between cultures, and while entire books could be written on this topic, this section aims to introduce a few key resources that we believe will be particularly helpful to you.

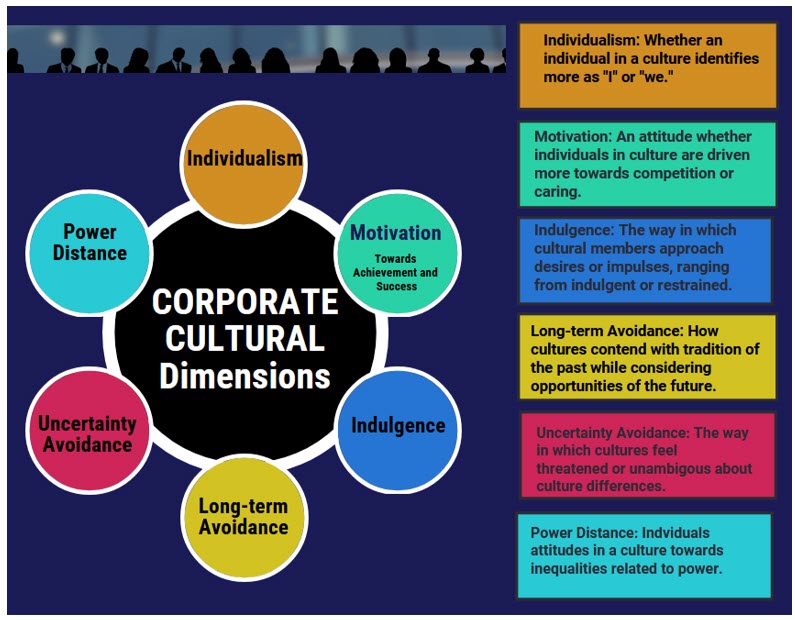

Researchers like Geert Hofstede leveraged his practical experience at IBM to develop a framework of six cultural dimensions that encapsulate common experiences across cultures. These dimensions—power distance, individualism, motivation toward achievement and success, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence continue to guide leaders and scholars. Organizations like the Culture Factor Group assist individuals seeking to understand these cultural differences by providing country comparison tools to help guide those who seek to understand and appreciate cultural diversity.

Figure 8.8—Six Cultural Dimensions

![]() Try the country comparison tool offered by The Culture Factor Group. Begin by selecting countries that you seek to compare. Once your selection has been made, visit the country comparison tool. Culture Factor Group. (2023). The Country Comparison Tool. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

Try the country comparison tool offered by The Culture Factor Group. Begin by selecting countries that you seek to compare. Once your selection has been made, visit the country comparison tool. Culture Factor Group. (2023). The Country Comparison Tool. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

The Culture Map

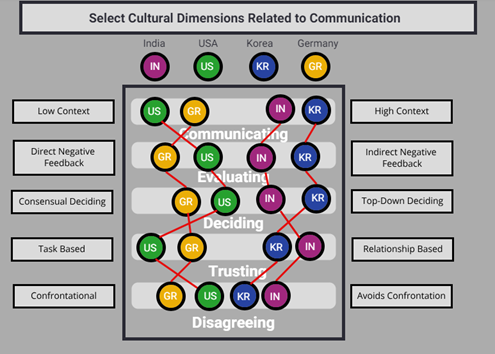

Erin Meyer, author of the Culture Map, helped to further Hofstede’s cross-cultural considerations by offering an eight-scale dimension to guide audiences. These dimensions help global audiences better identify cultural differences from a highly practical approach. The cultural dimensions of communicating, evaluating, persuading, leading, deciding, trusting, confronting, and scheduling help explain the various approaches that guide leaders as they interact with another culture. Table 8.2 explains the dimensions while the subsequent illustrations suggest how the dimensions may play out, interaction by interaction.

Table 8.2: Dimensions, Scale and Differences Explained

|

Dimension |

Scale |

Differences Explained |

|

Communicating |

Low to high context |

Low context speakers offer all details to others, being very specific and looking for the same from others. High context speakers let audiences read between the lines to get meaning and be surprised by low context details. |

|

Evaluating |

Direct to indirect negative feedback |

Those giving direct negative feedback are explicit and clear while those providing indirect negative feedback leave much unsaid or offer their reaction subtly. |

|

Persuading |

Principal-first to Application-first |

Principal-first communicators offer a theory or complex concept before presenting a fact, statement, or opinion. Application-first communicators lead with a fact, statement, or opinion. |

|

Leading |

Egalitarian to hierarchical |

Egalitarian leadership preferences desire group decision-making and may be comfortable with such a system or outcomes. Hierarchical preferences look to a top-down structure for such decisions. |

|

Deciding |

Consensual deciding to top-down decision-making |

Similarly, consensual decision-makers look to the group to have sign-off while top-down decision-making provides such an answer for everyone to then follow. |

|

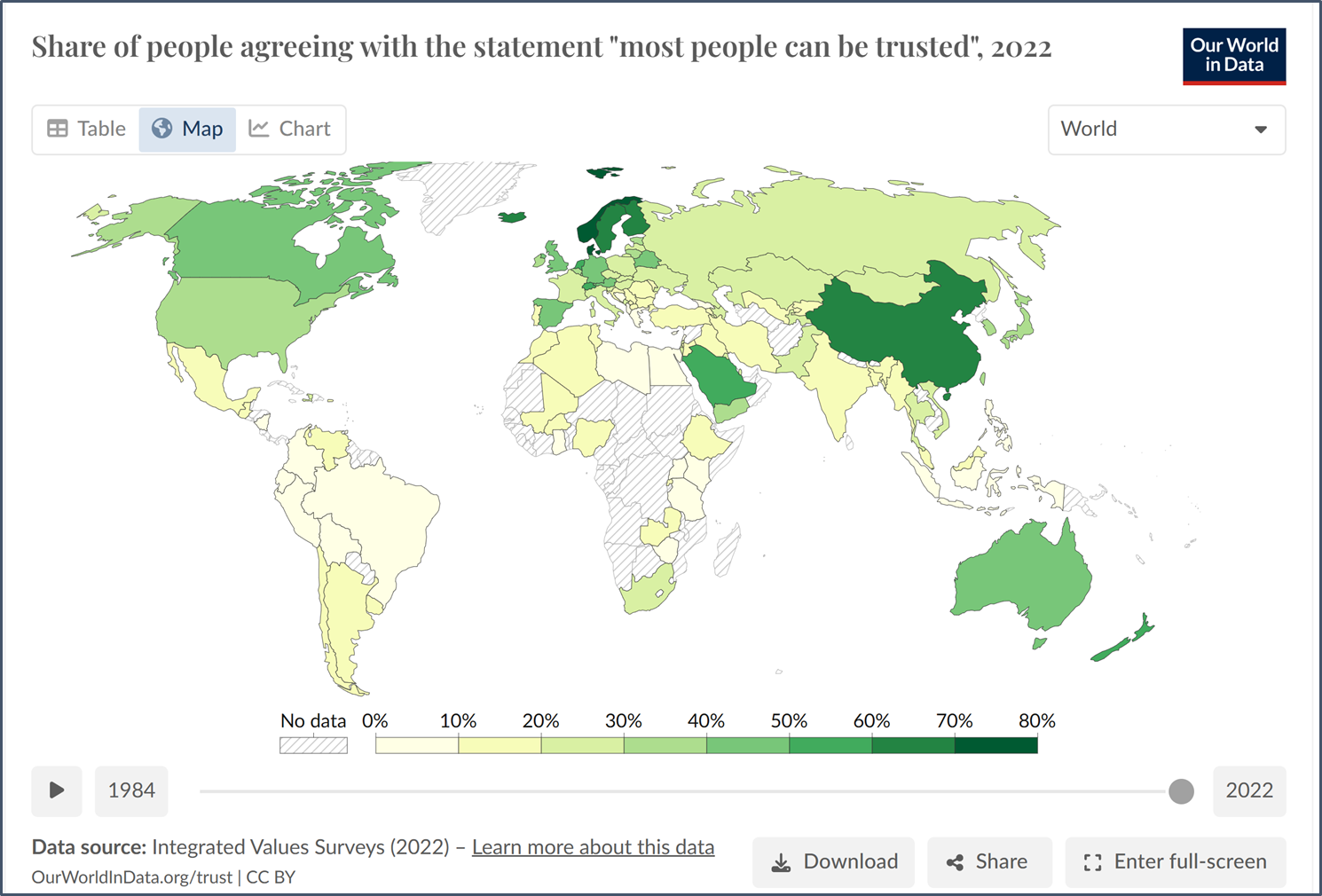

Trusting |

Task-based to relationship-based |

Task-based orientations see interactions to be largely centered on getting to work around a project or goal and if it goes well, trust is established. Relationship-based preferences like to know those they are working with before getting down to pursuing projects or goals. |

|

Disagreeing |

Confrontational to avoid confrontation |

Those that prefer confrontation to work through differences will be different from those communicators who avoid confrontation at all costs while not seeing it useful. |

|

Scheduling |

Linear to flexible time |

Linear time schedulers see meetings, appointments, and deadlines as a precise thing to be followed. They may see arriving early as actually being on time. Those in flexible time cultures tend to be approximate on start times, not seeing the need to rush from their timelier counterparts. |

Figure 8.9 illustrates how select dimensions relate to how communication may differ, culture-by-culture, in four specific countries. While audience members are never monolithic, leaders and communicators would be wise to heed these general parameters to better understand their audiences when approaching communication in such situations.

Understanding these cultural differences is just a starting point to recognize the ways in which different people connect. The next key step for any communicator is to identify specific actions to effectively communicate. First, listen to and observe your surroundings. Even when you are with a familiar work group, observe what they do daily. What are the spoken and unspoken patterns you observe? How do individuals interact and behave with each other? What is known by the in-groups, those that regularly work and interact in these spaces versus the out-group, those who do not. These key observations can begin to help you understand and see the differences.

Figure 8.9—Select Cultural Dimensions Related to Communication

Keeping in mind that differences do not mean deficiencies, a potential next step would be for a group to read resources like the Culture Map or take the online Cultural Profile available from Harvard Business Review in the next web resource offered in this chapter. So often, understanding diverse audiences begins by understanding ourselves and this important resource may help to illustrate key differences between you and other audience members from different cultures.

Finally, when comfortable, your working group should openly discuss and manage cultural differences. Sometimes this means acknowledging the cultural differences in daily actions. For instance, a low-context team member may acknowledge that the follow-up email they send after every meeting is simply a product of their cultural experience and not an assertion that other team members are disorganized, lazy, or not doing their work. Discussing this openly can prevent hours of unproductive soul-searching and bruised egos every time such a communication occurs. Similarly, the entire group can better understand that the manager providing very direct feedback may be operating from a cultural dimension to which they are very accustomed, rather than choosing to be critical. While that understanding alone may not help the team as they absorb the feedback, it can help everyone understand that the feedback is not personal but simply the way that manager communicates.

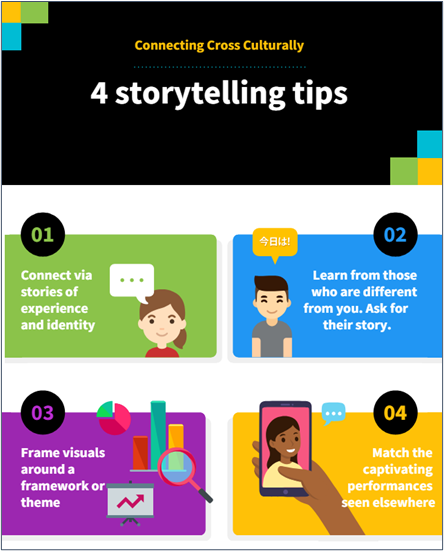

Considering cross-cultural communication also means examining the ways in which individuals connect routinely and a reminder of the importance of storytelling. Historical experience has taught us that individuals connect around needs, experiences, and hopes, which are often shared through story or narrative. Very often, these important discussions take place when one member connects with another via narrative and shared understanding. Storytelling is a phenomenon that exists beyond cultural dimensions and as a result, may be the precise way to connect with others via some tried and true practices depicted in Figure 8.10.

Figure 8.10—Tips for Connecting Cross Culturally

The Culture Map: The Future of Management. You can see the origins of the eight dimensions from Erin Meyer herself as well as hear this groundbreaking author comment on the future of management in the global organization based on her very important research.

![]() Meyer, E. (2014). The Culture Map: The Future of Management. [Video]. YouTube.

Meyer, E. (2014). The Culture Map: The Future of Management. [Video]. YouTube.

What’s Your Cultural Profile? This great resource from Erin Meyer and available via Harvard Business Review will allow you to take your own cultural profile and learn more about audience identity in your global organization. As you do, think about what surprises you. What was confirmed from your understanding of your own culture?

![]() Meyer, E. (2014). What’s Your Cultural Profile? Harvard Business Review: Business communication. https://hbr.org/2014/08/whats-your-cultural-profile

Meyer, E. (2014). What’s Your Cultural Profile? Harvard Business Review: Business communication. https://hbr.org/2014/08/whats-your-cultural-profile

One additional consideration is the ways in which persuasion may be different by culture. You will recall discussion in chapter one about the need in some cultures, like the United States, to be more upfront with an argument while following a “cut to the chase” or “time is money” philosophy. This contrasts with other cultures, such as those in China, who may be more indirect with a persuasive argument. For such speakers, it may be important to pay particular attention to how they begin their argument, make their points, and reach a decision with audience members. Table 8.3 offers important considerations for such speakers to consider, depending on the audience.

Table 8.3: Persuasive Style on How Some Cultures Communicate

|

Persuasive Style |

Key Components |

Countries Practiced |

|

Application-first |

✓Individuals begin with a fact, statement, or the idea being proposed before outlining why and how it will be implemented ✓Visuals lead with little background, often getting right to the point |

✓Australia ✓Canada ✓United States |

|

Principles-first |

✓Individuals begin with theoretical considerations, background, or other details before offering a possible solution or decision-point. ✓Visuals present this information for audiences to consider |

✓France ✓Germany ✓Russia |

8.2 Exercise 1: Considering Culture and Persuasion

Learning Objective #2—Identify competing ways to influence a global organization

Please read the case and identify the elements of cross-cultural communication that may assist you in developing responses to the case:

Please read the case and identify the elements of cross-cultural communication that may assist you in developing responses to the case:

Yuri, a Russian partner in a global company, listened to his American counterpart, Michael, as he presented his idea at a pitch session. Yuri found the message from Michael a little off-putting. Michael had come in and before barely sharing his slide deck, offered that the entire East European division should be melded into Yuri’s portfolio for Central Asia.

While the idea made good sense and was somewhat expected, Yuri was very surprised that Michael quickly came to this conclusion without any reasoning or evidence. Yuri would have preferred to see data, consider its merits, and then revisit after careful thought. It’s not that he objected to the idea entirely. Truthfully, he would likely agree, but it was the way Michael said it. Outside of this interaction, Yuri generally liked Michael. The two connected very well after discussing their families, experiences in the workforce, and common visions they had for the company’s future. While Michael continued talking, Yuri wondered if there had not been a better way to handle all of this . . .

- In reaching each other on this important message related to the company, what did Yuri, Michael, or both do wrong in connecting cross culturally?

- What strategies, if any, could have been used by Michael to reach Yuri on this decision?

- In handling this for future situations, do you have a recommendation for the company going forward?

8.3 Multigenerational Communication Issues

If you get the culture right, most of the other stuff, like great customer service, or passionate employees and customers, will happen on its own naturally.

—Tony Hsieh, former Zappos CEO

Company Culture and Multigenerational Communication Issues

Company culture plays out differently for large companies compared to small companies. In a large company, all leaders at the executive level are likely from the baby boomer generation. In fact, “roughly 80% of S&P 500 companies have baby boomer CEOs and approximately one-third of that group is 65 or older” (Potter, 2018, para. 4). As of 2016, the Pew Research Center indicated that millennials became the largest percentage of the workforce at 35%, and by 2025, 75% of the global workforce will be millennials (Fry, 2018).

In small start-up organizations, the owner influences the company culture and Millennials and Gen Z are more likely to start their own businesses. In a nonprofit, both the director and the executive board or board of trustees influence the organization’s culture. On the board, expect a mix of all generations, but directors and staff are normally not Baby Boomers. Wong and Main (2023) explained that “company culture is about the shared norms, values, attitudes, and practices that form the collective identity of your company [shaping] how things are done within your organization” (para. 6). The return on investment (ROI) is long-term. If you’ve ever worked in a toxic culture where generations don’t hold the same values, you can expect these symptoms: low employee engagement, high turnover, the blaming of politics, frequent use of the phrase “That’s not my job,” lack of trust, and high absenteeism.

Adding to the communication complexity of company culture is the multigenerational workforce. A leader’s role is essential in shaping the culture that bridges a multigenerational workforce. Different generations prefer different communication styles, may have biases (negative stereotypes), and hold different expectations for their employment. Although you may be well aware of the different generations, let’s review them.

The Five Generations of the Workforce

The following information is based on the Pew Research Center.

- Traditionalists or Silent (1925–1945)

- Traits: Dependable, straightforward, tactful, and loyal

- Communication style: personal, handwritten notes, not a fan of email, top-down approach

- Pew Research Center: Less than 2% of workforce and 9.8% of the population

- Baby Boomers (1946–1964)

- Traits: Optimistic, competitive, workaholic, team-oriented

- Communication style: Prioritize personal and formal communication. They appreciate phone calls, meetings, and memos. They may print out emails.

- Survey: Close to half (49%) of Baby Boomers are expected to or already are working past the age of 70 (Hicks, 2023).

- Generation X (1965–1980)

- Traits: Flexible, informal, skeptical, independent

- Communication style: prefer communication that is efficient, can easily adapt to digital, work hard play hard

- As of 2021, 35% of those employed include Generation X (Kuligowski, 2021).

- Millennials (1981–1996*)

- Traits: Competitive, civic and open-minded, achievement-oriented, well educated

- Communication style: Digitally adept, which shapes their communication preference, IMs, texts, specific internal platforms like Slack, want ample feedback and recognition.

- Less likely to remain at one organization. By 2025, 75% of the global workforce will be millennials (Fry, 2020).

- Generation Z (1997–2012*)

- Traits: Global, entrepreneurial, progressive, less focused

- Communication style: Digital natives, tech-savvy, quick learners, expect instant communication, but also IMs, social media, texts, like self-direction.

- Seek organizations that align with their values, will self-identify as digital addicts.

* Using the new definition period for each generation from the Pew Research Center. These classifications are globally understood and recognized. More information is coming for Gen Z as they come of age.

Let’s explore the number one issue of low employee engagement—knowing what is expected.

Low employee engagement: The value of engaged employees is their entrepreneurial spirit. They own their work. And as owners, they are motivated to drive change and contribute to innovation. Disengaged workers are less productive, more stressed, and less secure. Gallup’s 2023 U.S. survey indicates that 33% of employees were engaged in 2023, which means that 67% of employees are not engaged. Actively disengaged employees, or loud quitters, are at 16%, which is down from 2022 (Harter, 2024). “The most fundamental engagement element is knowing what is expected of you,” and the fallout of COVID-19 is that “70% of managers report to Gallup that they have no formal training in how to lead a hybrid team” (Harter, 2024, para 10).

If your work involves teams, consider using the CliftonStrengths Assessment from Gallop. This assessment measures your unique talents and categorizes them into 34 Clifton Strength themes. Knowing your strengths can help you leverage them, especially in a team setting. According to CliftonStrengths, it is important to discover the collective talents of your team. “To successfully manage or lead others, you must individualize your approach. You must understand what makes each of your team members unique. And you must lead meaningful conversations about performance that focus on what each person naturally does best” (Gallup, 2024). There is more about CliftonStrengths in Section 8.6. As a reminder of the 7Cs of communication, good communicators should be clear, concrete, concise, complete, courteous, and coherent.

Leaders are expected to be good communicators, so how can we leverage data visualization or communication tools to support better communication?

Key Strategies for Communicating Across Generations

Balanced Hybrid Work Model: Bridging cross-generational communication gaps can be done through a balanced hybrid work model. Everyone has experienced COVID-19, and it certainly changed how we communicated during the pandemic’s rage across the globe. The lessons we learned impact communication in the present. A Forbes expert panel recommends a blend of face-to-face meetings and virtual meetings (Uzialko, 2024). Training should be delivered across all generations to make sure everyone can use the communication and collaboration tools effectively.

Multichannel approach: Leaders need to utilize a diverse range of communication channels. This need is why you see so many communication channels: Slack, Google Chat and Google Meet, Chanty, Microsoft Teams, Basecamp, Zoho Cliq, and dozens more. The point is that leaders need to provide a multichannel approach, perhaps an email to the Traditionalists and Boomers and an instant message (through Slack or an alternative) to other generations.

Tone, jargon-free, inclusive language: Consider the seven Cs of communication: clear, concise, concrete, correct, coherent, complete, and courteous. Tailor messages to have the right tone and free of jargon. Stay central to the topic. If your team has global members, communicate to them in their preferred language, avoid slang and colloquialisms, be conscious of time zones, and be careful of humor.

Role of AI and automation: AI-powered tools can help with internal communication (personalizing communication), predict communication patterns to help you anticipate communication needs. For example, have you ever come into a meeting late and felt like saying, “What did I miss?” Leveraging AI means that now you can ask the AI questions like this and even a question like “Did my name come up for any projects?”

Embracing remote communication methods: Use Zoom/Teams/Slack or other virtual meeting software features to their fullest by adopting interest-based conversations instead of position-based conversations. Choose the whiteboard before the meeting. Set up your polls (for feedback) before you meet. All virtual meeting software has a long list of whiteboards. In Exhibit 8.1, Zoom has templates ranging from strategy to planning, brainstorming to ideation, mapping, diagramming, meetings, and retrospectives.

Exhibit 8.1—Templates in Zoom

Remote Meeting Strategies

Additionally, the whiteboards are visual cues to the members of your team. They will retain important facts like deadlines better when they work on it visually in collaboration with the team.

- For multigenerational teams pair partners within the team (one techy and one not) so participants who have fewer technology skills (normally Baby Boomers) can participate comfortably.

- For all team members, request a page summary to send out to the team.

- For all team members, record the meeting.

- For all team members, set up a poll using feedback questions to make sure everyone has the opportunity to contribute.

- For all meetings, identify trends across the generations and support a balance of several communication styles.

- For all meetings, adapt a policy of camera on, so you can facilitate verbal and nonverbal communication.

- For all meetings, work from an agenda, and set a time limit. The majority of employees struggle to get work done because of the sheer number of communications they receive.

- For all meetings, meet regularly and ask team members to display availability. Different organizations will have different needs, but every organization should have communication guidelines.

- For meeting follow-up, have periodic check-ins (either daily or weekly). A list of check-in questions can help you determine progress, employee focus, employee concerns, and so on. You can even do a periodic emotional check-in to see if your team members are feeling stressed.

- For all meetings, cultivate culture. Share core values and the company’s mission and/or visions. Recognize employees publicly. Plan team bonding and networking—remote coffee breaks, achievements like employee-of-the-week, and use icebreakers to start a meeting. A good icebreaker for building relationships with a global team is using a map where individuals can pin their location to answer the question, “where are you from?” This template is shown in Exhibit 8.2. Just seeing where your team calls in from can help others understand the challenge of time zones, especially if you include that information as part of pinning where you are located!

Exhibit 8.2—Zoom Whiteboard: Where Are You From?

8.3 Exercise 1: Evaluate a Recent Meeting

Learning Objective #3—Share strategies for multigenerational communication issues

Part 1: Investigate Zoom or Teams and discuss the potential whiteboards that you could use at your organization to help improve efficiency, brainstorming, or collaboration.

Part 1: Investigate Zoom or Teams and discuss the potential whiteboards that you could use at your organization to help improve efficiency, brainstorming, or collaboration.

Part 2: Discuss a recent meeting (either remote or face-to-face) that had some challenges. Discuss one of the challenges. What strategies were used to resolve the communication issue or what strategy should have been used to resolve the communication issue?

Part 2: Discuss a recent meeting (either remote or face-to-face) that had some challenges. Discuss one of the challenges. What strategies were used to resolve the communication issue or what strategy should have been used to resolve the communication issue?

Part 3: Considering the diverse communication preferences and technological proficiencies across different generations in the workplace, how can leaders effectively leverage data visualization or communication tools to support better communication in a balanced hybrid work model?

Part 3: Considering the diverse communication preferences and technological proficiencies across different generations in the workplace, how can leaders effectively leverage data visualization or communication tools to support better communication in a balanced hybrid work model?

8.4 Data Visualization Techniques to Fill the Gaps

Everybody needs data literacy, because data is everywhere. It’s the new currency, it’s the language of the business. We need to be able to speak it.

—Piyanka Jain, speaking with MIT Sloan

It is no surprise that organizations face a rapidly changing landscape of contemporary issues. Effective communication has emerged as a cornerstone for success, partially in the realm of data-driven decision-making. “In a recent survey of analytics leaders, 67% said organizational culture is the biggest barrier to becoming a data-oriented company” (Mayor, 2021, para 8). A data-oriented organization makes strategic decisions based on data; however, “only 20% of analytics insights will deliver business outcomes through 2022 according to Gartner research” (Mayor, 2021, para 3). As organizations strive to capture the power of data to drive innovation and communicate through storytelling, the audience is becoming increasingly diverse. This section delves into the intersection of data visualization and storytelling techniques as dynamic tools for communication, with a focus on the needs of the diverse composition of modern teams.

As workplaces become increasingly diverse in terms of gender, culture, and generational backgrounds, the challenge of effectively communicating data insights to a broad spectrum of team members has become more challenging. Added to this mix is the necessary recommendation for how data are visualized from a DEI point of view. DEI is discussed more thoroughly in Section 8.5. This section explores strategies for crafting visual narratives that resonate with multiple genders, considers cultural barriers, and engages multigenerational cohorts. The point here is to cultivate a climate of technical data analysis, human-centric storytelling, and collaborative decision-making processes that harness the collective intelligence of a diverse team.

Design choice that considers the science behind visual perceptions and cognition is important to communicate effectively. Drawing upon insights from psychology, sociology, and communication theory, this section adopts a user-centric approach to data visualization and narrative construction.

Before starting this section, review some of the current population statistics:

- As of 2020, Baby Boomers are at 18.6%, Generation X is at 34.8%, Millennials are at 38.6%, Generation Z is at 6.1%, and the traditionalist or silent generation is at 2% (Purdue Global, 2020).

- “As of February 2023, women 16 years and over make up 55.4% of all U.S. employees” and “women’s wages equal 83.6 percent of men’s wages” (Reiners, 2024, para. 15–17).

- The 2015 census data show 56% of Millennials are white, whereas 75% of Baby Boomers are white.

- “Diverse companies have 2.5 times higher cash flow per employee” (Reiners, 2024, para 22).

- Companies that are diverse (gender, race, and culture) are more profitable (Reiners, 2024).

Design Strategies

The following strategies are based on working with a diverse team or presenting to a diverse audience.

Strategy #1—PechaKucha: Plan a Beginning, Middle, and End in 7 Minutes

Emphasize the personal benefit in the introduction concisely so you can quickly get to the major point. Plan to reestablish said personal benefit in the conclusion (McMahon, 2016). Just as important, you need to develop techniques, so the presentation does not drag. A Japanese management style called PechaKucha is an approach where you have 20 slides timed at 20 seconds each. The slides automatically advance giving you less than seven minutes to tell your story, and most slides should complement the speaker when vocalizing (Eckfeldt, 2019). Data Visualizations that use charts and graphs need to focus—so automatic zooming or animation might be required.

To effectively connect using the PechaKucha, use these techniques:

- Personalized introduction: Begin with a brief but impactful introduction. Tailor this introduction to resonate with diverse audiences. The introduction does not mean you are introducing yourself. Introduction means sharing personal anecdotes, sharing experiences, using images that make sense to your audience, and using metaphors that fit your audience. All audiences prefer a visualization in context. Test it out before presenting.

- Utilize structured storytelling: Ensure each segment flows seamlessly into the next. Use the CASS framework and keep your storytelling framework universal in design. Be careful with humor. Illustrate the main point clearly. Always show impact on the bottom line.

- Visual technique: Use techniques that resonate, such as (a) simple and clear charts, (b) color considerations, (c) iconography and symbols, (d) infographics, and (e) interactive visualizations for your tech-savvy audience members.

- Cultural context in imagery: Incorporate culturally relevant imagery and references—that is, if you use images, make sure they include diverse backgrounds. Avoid macho sports metaphors.

- Accessible design: Alt tags, color contrast adjustments

- Do NOTs: On occasion, you might be tempted to use a data visualization that makes you look like a technology wizard. Fight this! The sole purpose for data visualizations is to “help you tell stories by curating data into a form easier to understand, highlighting the trends and outliers,” . . . and that means . . . “removing the noise from data and highlighting the useful information” (Tableau, 2020, para. 8).

![]() Title: PechaKucha: Visual Storytelling That Celebrates Humanity. Link: https://www.pechakucha.com/

Title: PechaKucha: Visual Storytelling That Celebrates Humanity. Link: https://www.pechakucha.com/

Strategy #2—Get to the Point!

One of my favorite quotes made in the Storytelling With Data book is “If you only had a limited amount of time or a single sentence to tell your audience what they need to know, what would you say?” (Knaflic, 2015, p. 39). Mitchell and Deckard have reviewed thesis and final projects for over a decade. Imagine a presenter receives instructions to present for 15–20 minutes. The student has great visuals sharing the background and challenge or issue at an organization. If you are sitting in the audience still waiting on the recommendation and the presenter is already fifteen minutes into the presentation, you may be so frustrated that you stop listening. And you may be thinking, “Get to the point!” Even visuals can suffer from “getting to the point.”

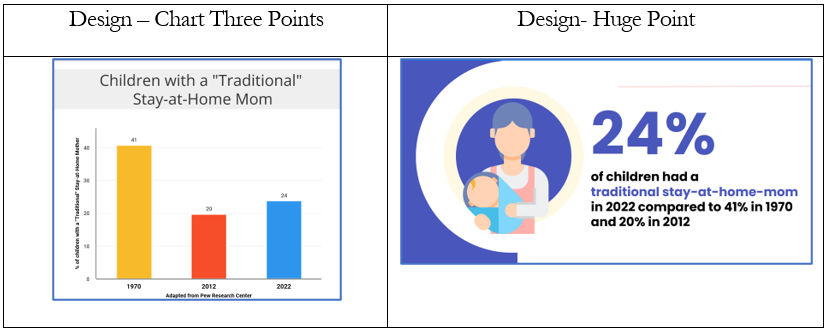

Which is better when you review Figure 8.11? The graphic on the right has a “get-to-the-point” component since the focus is on 24% in 2022.

Figure 8.11—Graphic Design Makes a Difference

Regardless of gender, cultural, or generational preferences, everyone prefers clear and concise key points. Now look at specific data visualizations.

Strategy #3—Use the Appropriate Data Visualizations

Here are some other key points experienced by the authors. These guidelines apply to presenting to either gender. Consider this section the basics of data visualization techniques using Excel and a few references to Power BI. Keep in mind that previous chapters shared other types of data visualizations (word clouds, infographics, maps, etc.).

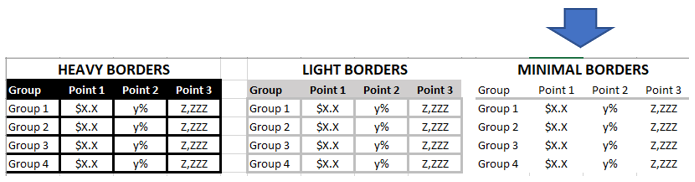

1. Tables: Do not use tables in a presentation unless you have no choice. If you must use a table, get rid of the borders and grid lines or the audience will focus on the borders and gridlines! The best visual in a large room presentation has minimal borders. See Figure 8.12.

Figure 8.12—Minimal Borders Best for Large Venue

2. Heatmaps: Heatmaps were discussed in earlier chapters but let’s consider why this is a good choice for a diverse audience. The appeal of heat maps can vary based on individual preferences, demographics, and cultural backgrounds. In terms of gender, research suggests that males and females may have different cognitive preferences and visual processing styles, which could impact how they perceive and interpret heat maps.

Generational differences: Baby Boomers, who grew up in a different technological era, may have different levels of familiarity and comfort with data visualization techniques like heat maps compared to millennials, who are often more digitally savvy. Again, individual preferences are most likely to drive their understanding of a heat map. A heat map can be produced in Excel using conditional formatting. Creating a correlation matrix is available in Data Analysis (an add-in to Excel) for the Data table. Then you can set up conditional formatting. Refer back to Chapter 3 (Table 3.16: Heatmap Shows That Board Members and CEOs Are Not on the Same Page) to see the benefits and how easy it is to see patterns.

3. Scatterplots: Scatterplots are great for showing the relationship between two things, but they aren’t used as much in business, mostly because perhaps folks are not as familiar with them. Scatterplots are much easier to understand if you show the average or modify the chart with a band of color (this is shown in Section 3.7). Another way to show a relationship is with maps (see Section 3.7). Individual preferences and experiences play a significant role in determining which generations in the workforce prefer scatterplots.

Generational differences: Younger generations may be more receptive to scatterplots, but factors such as job role, industry, and personal interests, may play a part in how well younger generations understand them. You would expect the traditionalist generation to be less familiar with scatterplots, but scatterplots with average and customized bands of color can add value for all generations.

4. Line graphs: Line graphs are used to plot continuous data. Adding an average to a graph adds value. Line charts are great for long-term trends.

Generational differences: All generations understand a line graph, but not all line graphs are equal. For example, you can create an animated line graph using Flourish. This will appeal to the tech-savvy generations, more specifically the Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z cohort.

5. Slope graphs: A slope graph, introduced by Edward Tufte in 1983, is useful when you have two points of comparison, and you want to quickly show increases and decreases. An example would be an annual employee satisfaction survey, and the analyzers want to display the changes quickly between 2023 and 2024.

Generational differences: Traditionalist and Baby Boomers will like slope graphs because it is an easy way to measure change. The tech-savvy cohorts will appreciate the ease of identifying patterns but may feel just as comfortable looking for a pattern in a sparkline in Excel.

![]() Title: Excel Slope graph. By: Online Training Hub. Template Link: https://www.myonlinetraininghub.com/excel-slopegraphs

Title: Excel Slope graph. By: Online Training Hub. Template Link: https://www.myonlinetraininghub.com/excel-slopegraphs

6. Bar Charts: A bar chart is familiar to your audience. The audience can easily see the biggest and smallest. There is one rule you should never break. Bar charts must have a zero baseline. Although this is discussed in previous chapters, we want to emphasize the importance of using a zero baseline. If you don’t use a zero baseline, you misrepresent the data by exaggerating differences and losing the trust of your audience. It violates a visualization principle. If you want to revisit this, see the figures in Chapter 2.

Generational differences: Violation of the zero-baseline principle can end up breaking the trust you work so hard to build with your audience. This is true regardless of the generation. Use a zero baseline. Otherwise, you can introduce significant issues that compromise integrity and effectiveness. Don’t lose your credibility!

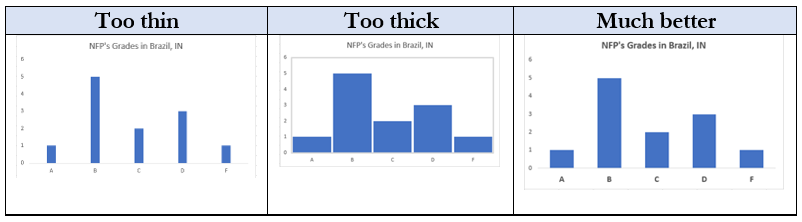

7. Column Bar Charts: The column bar (also vertical bar chart) can contain multiple columns, but consider your audience and what you want them to compare. Too many data series (columns), and it becomes difficult for your audience to visualize and connect to the “insight” you are trying to convey. Use your spacing appropriately. Figure 8.13 is a grading of nonprofits in Brazil, Indiana (this is just for illustration purposes). Besides the spacing, the gridlines were removed, and in the third illustration, the text was increased in size and made bold.

Figure 8.13—Column Bar Chart Comparison

Generational differences: Both Baby Boomers and traditionalists may have been exposed to traditional forms of data presentation (printed!) and have seen column bar charts frequently. Tech-savvy cohorts are used to the column bar charts and find them intuitive.

Is there a better chart? As you review your charts, consider changing the vertical bar chart to a horizontal bar chart because horizontal bar charts are easy to read. Baby Boomers are more accustomed to viewing information in a left-to-right format, making horizontal bar charts more intuitive. Think about how you read—starting at the top left and moving across the screen—this means the eyes can read the category names before the data in a natural process similar to reading.

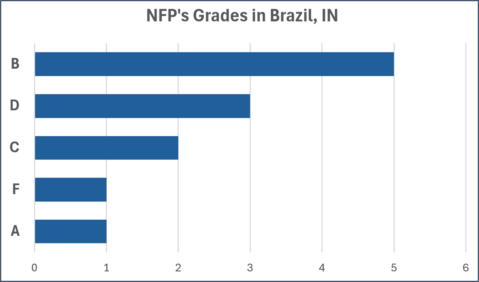

8. Horizontal Bar Charts: As mentioned earlier, a horizontal bar chart is familiar to your audience because the data are organized from the far left corner and across—very similar to the way we read. Horizontal bar charts can have single series or multiple series. They are especially good when the information labels are too long to appear clearly on the x-axis of a vertical bar chart. A second thought is to consider if organizing the chart from biggest category to least category will help your audience get the big picture. The reader will see the top horizontal bar first, so this makes sense. However, if your categories are grouped by age, or donation size, or letter grades, keep the categories in order! Otherwise, as shown in Figure 8.14, the audience may struggle to make sense of it. So the natural order is best.

Figure 8.14—Horizontal Bar Chart: When Sorting Causes Confusion

Figure 8.15—Horizontal Bar Chart: Correct Order

Generational difference: Baby Boomers and Traditionalists are accustomed to this format and find it easy to read (not Figure 8.14 though!). Individual preferences can vary within each generational cohort. What is most important is selecting the appropriate chart type for effective communication.

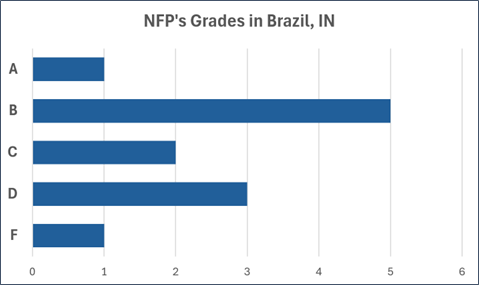

9. Multiple Series—Column Bar Charts: Bar charts with multiple series can become crowded. The chart in Figure 8.16 shows an example of a survey where administrators and board members rated the staff and the staff rated themselves. The survey has eight groupings of three variables each. The ideal number of groupings is a total of 12 bars (or in this case four groupings) for a presentation, so pick the groupings that are significantly different. For example, there is a big difference between how the administrators and boards saw the staff’s patience compared to how the staff see themselves. There is an effective use of colors that is consistent across all groupings. The survey ratings are 0–10, and no distortion or exaggeration is apparent.

Figure 8.16—Multiple Series Column Bar Chart

The Soft Skills Survey Results chart could be better though. It could contain a more descriptive title and a date.

Generation difference: When you start including multiple series of data, Millennials and Generation Z often prefer interactive visualizations. For example, this could be designed so you could compare various combinations of the survey. So comparing administrators to staff might be more important than including the board. In this chart, administrators and board members rated the staff and the staff rated themselves.

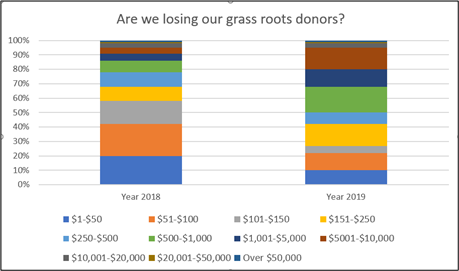

10. Stacked Vertical Bar Charts: Stacked bar charts are used to show quantity, dollars, or a percentage that adds up to 100%. The illustration shown here is from a not-for-profit and they’ve grouped their donations by the size of the donations. Although they raised a similar amount of money in 2018 and 2019, the makeup of donors has changed. When you look at this chart, do you think a change in marketing is needed? And when you view Figure 8.17, do you agree with the question, “are we losing our grass roots donors?”

This chart has almost too many categories. According to Vora (2019), the maximum number of bars to show trends or relationships is 12 bars (12 categories). This chart has 11, but you can answer the question by reviewing the chart.

Figure 8.17—Stacked Vertical Bar Charts: Too Many Categories

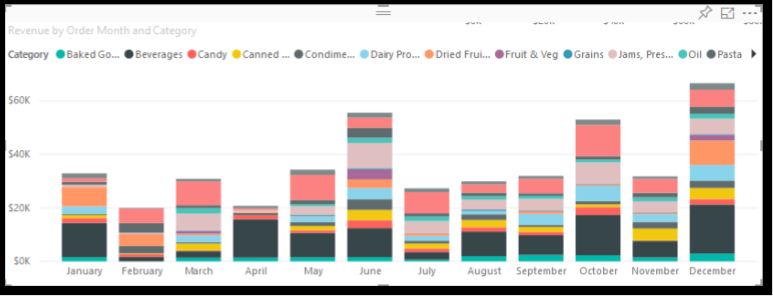

Microsoft Power Business Intelligence (BI), suggests using stacked bar charts if you use slicers. Slicers are a type of visual filter. Once you see the charts, you will understand why! Figure 8.18 does not have a slicer, and these data are very difficult to understand. But if you select an item from the legend (e.g., Candy), it will show the revenue for that item for each month. You can also select multiple products by using the control key to select two or more categories. However, this may not be intuitive to a new user of Power BI.

Figure 8.18—Power BI Stacked Bar Chart, Where Every Category Can Be a Slicer

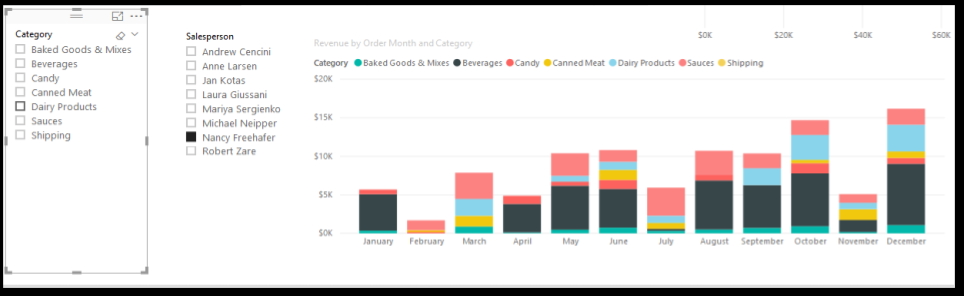

The next two charts show how adding slicers makes it easier to understand. This is the same dataset as seen in Figure 8.18, but the slicer allows us to filter on the salesperson (in this case, Nancy), and on the category of goods. Slicers are a wonderful tool for helping understand complex data, and showing them with the charts means even novice users of Power BI will know what to do to trigger a filter.

Figure 8.19—Power BI With Salesperson Slicer Selected

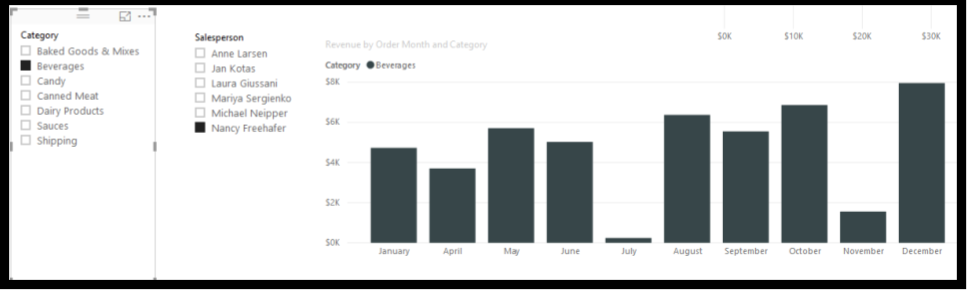

Figure 8.20 shows two slicers in play. The slicer for the salesperson (Nancy) and the corresponding dollar in sales of beverages she has sold each month.

Figure 8.20—Power BI With Two Slicers Selected: Salesperson and Beverages