1 Communicate Results

Data saturation is everywhere. We’ve often had the belief that more is better; however, that actually isn’t true in the case of data. The rapid rise in our ability to collect data hasn’t been matched by our ability to support, filter, and manage data. As an example, think about the first problem that people complain about when a city experiences great growth—the roads are too crowded. The infrastructure can’t keep up.

—Sarah Spivey, Forbes 2020 World’s Most Influential Chief Marketing Officers

What Do You Think?

Michelle, the CEO of a midsize engineering company, was in another one of those meetings she had grown to dread in the three months she had been running the growing and in-demand firm. Dane, one of her brightest lead engineers, was supposed to be explaining a new product line to the management team. The line would be unveiled in the next few months. Appearing somewhat nervous, Dane had been allotted just 20 minutes on the official meeting agenda but had already spent 15 minutes discussing the project’s background. Nearly every decision-maker in the room was already familiar with the need for the project and had been for some time. At 10 minutes in, Michelle, squirming a bit in her seat, knew he would never get to the crucial part that everyone desperately needed to hear. Specifically, the management team needed to understand the functions of the new product line. They also needed to understand the benefits for existing clients and how to market in an organization-wide, all-hands-on-deck capacity.

Michelle, a successful executive who had come up through the sales side, had been handed the reins of the organization after the start-up founders decided to take a step back from the day-to-day operations. The founders, who were also engineers, had been impressed by the powerful way that Michelle had described her vision for the organization over a series of get-to-know-you meetings. Michelle was energetic and succinct and used visionary language that portrayed a vivid story of the company’s future. She credited these abilities to her work experience sharing data with clients who appreciate efficiency and effective reporting. This day, Michelle had purposely given Dane, the best engineer on her team, a 20-minute slot. She had already summed up what she thought he needed to do effectively to bring the team up to speed.

Dane struggled through the background information, unaware he was repeating information most decision-makers in the room already knew. The voluminous slide deck he prepared was full of data and excessive bullet points, and each page appeared identical to the next as he droned on and on to the room of important insiders. Michelle, who prided herself on understanding the details of company initiatives and products, found herself struggling to follow along. Her attention drifted off, and other audience members were noticing. She worried about moving Dane along in the presentation, fearing it might aggravate his nervousness and cause the meeting to go further adrift. She also noted that Dane’s presentation was reflective of many such presentations that lost their focus in presenting important ideas, relevant data, or discernible takeaways for audiences. As Dane continued, Michelle wondered if there was something different her team could do to be more influential during these important moments. . . .

How does this case relate to your own experiences at work, home, or school? What do you think Dane could have done differently with his pitch? What outcomes or goals should Dane have kept in mind? Who is the audience in this case, and how do you think they felt? Why should Michelle be concerned about the communication of her team? Do you have any suggestions for her moving forward?

Introduction

Michelle’s quandary about the missed opportunities for better communication in her organization is not an isolated example. Her situation may have invoked some sympathy from your own experiences and feelings of frustration as you thought through a range of similar struggles. Those struggles may have included memories of a work meeting where communicators never got to the point or a class lecture that contained information that seemed indecipherable. It may have also included a close friend or loved one who aimlessly guided their half of a conversation to everywhere except a finish.

The failure of presenters to share important information seems almost like a rite of passage in many leadership tenures and organizational cultures. Failure to reach an audience in these situations seems almost the rule instead of the exception. As a result, the need for a speaker to reach an audience is more important than ever, particularly when the goal of their message is to gain buy-in, to reach a decision, or for action to be taken on the part of the audience members.

This text provides readers with tools to communicate their ideas and data clearly. Clarity is key to connecting audience members to important information. Throughout this text, you will see additional resources and learning objectives to guide the journey. While not everything can be learned in this text (applied practice is needed), the information will provide a solid foundation for readers to discover tools that work for them and that reach their intended audience. To that end, the following chapter unpacks essential communication models on which the following processes are based, accompanied by discussions surrounding audience analysis. This chapter then turns to the powerful use of persuasion and storytelling to deliver our messages.

Chapter 1 addresses the following learning objectives.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- LO 1: Identify communication models that predict connection and identification between speaker and audience.

- LO 2: Describe the various aspects of audience perception and of speaker and message, and conduct key analysis before creating or delivering a presentation.

- LO 3: Flex between direct and indirect persuasion models to deliver influential communication.

- LO 4: Listen critically to identify powerful narratives and use effective storytelling to frame meaningful messages.

Key Terms: channel, context, direct and indirect persuasion, environment, feedback, message, narratives, presentation software, sender, source, storytelling

1.1 Communication Models and Management of Information

It is the responsibility of the sender to make sure the receiver understands the message.

—Joseph D. Batten, leadership scholar

Considering the Complexity of Communication in a Busy Sender-Receiver World

Too often in our communication experiences, we find ourselves overwhelmed with information as we struggle to assign meaning to the plethora of messages we are receiving. As our opening case already displayed, these moments can incite a flurry of emotions and confusion. Those familiar with travel or navigation can appreciate the feeling of being in “uncharted waters” despite having a clear travel plan or destination.

In such moments it is easy to miss important parts of the message necessary for understanding. Think through your personal experience in situations where others are sending you messages. You may spend a lot of time trying to determine the actual message you are receiving. You might also wonder about the messenger—their motives and how you fit into the messenger’s plans. Additionally, you may spend time thinking about a potential response and how others will process your response. Those moments may feel confusing, and we may find ourselves with more questions than answers . . . and a strong desire to put off any decision at all. Many audience members are reluctant to voice their confusion out of fear of embarrassment—their own or the speaker’s.

The Communication Process as an Ongoing Play Between Sender and Receiver

In situations like this, it’s common to feel responsible for our failure to understand. However, it’s essential to recognize that understanding is a joint responsibility between the messenger and the recipient. The way the message is conveyed plays a critical role. Assumptions about the recipient’s knowledge, vocabulary and terminology, or bias can hinder effective communication. As authors, we view communication as a multifaceted and dynamic process that occurs between individuals within their environment and amid the context of their circumstances. Imagine communication as a complex theater performance—a play unfolding between two people.

The Communication Process: A Play by Mitchell and Deckard

The play starts with a sender, a coequal actor in our play and otherwise known as an individual seeking to impart information to the receiver. The sender and receiver approach each other with their own unique culture, experiences (professional and personal), perceptions, biases, and knowledge. We can call those background considerations context. Both the sender and receiver may be aware of, indifferent to, or oblivious to the differences between themselves and others. Together, sender and receiver operate on a channel of communication that includes a plethora of tools that can be issued verbally or conveyed nonverbally through facial or body language, written word, or items they produce. As you can see, there are a great deal of factors present for every communicator as they convey their message, which ideally is the information they seek to impart to their coequal actor on this proverbial stage.

While we all enjoy a play with a happy ending, this acting is a bit more complex. It includes some other details that we must first decipher. First, returning to those concepts of verbal and nonverbal, we must consider the reactions that the sender and receiver give each other during this communication process. We call those reactions feedback, and it includes words, facial expressions, and body language expressed by either party while processing the message. Feedback can be abundantly clear or very subtle, with the potential for both characteristics to occur within seconds of each other during our communication play. We also must consider another concept, noise, as it becomes an important element of the communication process and is prominent in our play. Noise refers to anything in the context, channel, or message that delays, disrupts, distracts, or prevents the otherwise normal flow of communication. Noise can be caused by anything, whether we notice it or not.

By the way, the ongoing communication doesn’t necessarily follow a script; it’s an infinite play. Achieving success in this communication play can be hindered by many distractions. What is the audience noticing? Let’s revise the concept of “noise” within our play. Imagine the receiver of the message arriving at a 9 a.m. meeting after a difficult and distressing morning. Upon arriving at work, they are bombarded by four hot-button problems requiring immediate resolution. Simultaneously, their office mates and email inboxes demand attention. To add to the stress, they skipped breakfast due to a family matter that couldn’t wait until after work. And guess what? That same urgent matter will likely require additional attention during their nonexistent lunch break. All these profound factors contribute to the noise that disrupts communication between sender and receiver in our play. Sometimes, the noise is barely discernible to the sender, or perhaps the sender faces similar challenges while trying to convey their message through the channel.

Introducing the Credible Speaker and Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

The factors that make communication complex also highlight the need for practitioners to consider their messages for audience-centeredness, clarity, and organization. Aristotle, a Greek philosopher and scholar, encouraged a combination of ethos, pathos, and logos. He contended that the well-rounded speaker could reach audiences in highly effective ways via these three appeals. Ethos refers to the credible speaker—their experiences and character as the reputation that audience members come to know and trust. Pathos considers the emotion a speaker conveys in their words and, more importantly, how those feelings are considered by audience members. Logos describes the logic or reasoning through evidence that a speaker utilizes to reach their audience. Logos can be the very structure of an argument, or it can consider the best types of evidence to use with a particular audience. Together, these three appeals act as strong pillars that support the speaker, their connection with the audience, and their argument.

![]() Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. You can learn more about the use of ethos, pathos, and logos from this video produced by the Texas A&M Writing Center. Tamu Writing Center. (2020, Jun 12). Ethos, Pathos & Logos. [Video]. YouTube.

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. You can learn more about the use of ethos, pathos, and logos from this video produced by the Texas A&M Writing Center. Tamu Writing Center. (2020, Jun 12). Ethos, Pathos & Logos. [Video]. YouTube.

![]() Aristotle: A Complete Overview of His Life, Work, and Philosophy. Aristotle’s life and work extend into a wide swath of learning and philosophy. This article by Viktoriya Sus for the Collector, which produces daily articles on ancient history, philosophy, art, and artists by leading authors, explores this influential thinker. Sus, V. (2023, May 16). Aristotle: A Complete Overview of His Life, Work, and Philosophy. The Collector. https://www.thecollector.com/aristotle-life-works-philosophy/

Aristotle: A Complete Overview of His Life, Work, and Philosophy. Aristotle’s life and work extend into a wide swath of learning and philosophy. This article by Viktoriya Sus for the Collector, which produces daily articles on ancient history, philosophy, art, and artists by leading authors, explores this influential thinker. Sus, V. (2023, May 16). Aristotle: A Complete Overview of His Life, Work, and Philosophy. The Collector. https://www.thecollector.com/aristotle-life-works-philosophy/

1.1 Exercise 1: Identify Ethos, Pathos, and Logos in an Appeal

Learning Objective #1—Identify communication models that predict connection and identification between speaker and audience

Consider the last request you heard. Think back through the last 24 hours of your day and the last time someone asked you to consider something or do something of significance. What evidence of ethos, pathos, and logos did you hear in their appeal? Do you think the sender of the message intended their appeal to have those aspects? How do you think they specified their appeal to you as an audience member?

Consider the last request you heard. Think back through the last 24 hours of your day and the last time someone asked you to consider something or do something of significance. What evidence of ethos, pathos, and logos did you hear in their appeal? Do you think the sender of the message intended their appeal to have those aspects? How do you think they specified their appeal to you as an audience member?

Communication Models That Decipher the Complex Communication Process

If you sense that this text on data visualization and storytelling leans heavily toward audience focus, trust your senses. Effective communication, where sender and receiver manage to relay the desired message despite the distraction of noise, must start by considering the audience before creating the message. This consideration should occur even in the split seconds available in the bustle of life. That said, regarding communication, an audience-centered approach has not always been the case despite Aristotle’s advice on ethos, pathos, and logos.

As communication models from the last century illustrate, we’ve only recently begun to fully consider the complex interplay of sender and receiver. The Linear Model, offered by Sharron and Weaver (1949) relied solely on the messenger for analysis. Osgood and Schramm’s Interactive Model, offered in 1950, considered the receiver of the message but did not fully capture the nuance of verbal and nonverbal communication in a busy model. Both the Linear and Interactive Models reflect times in society where speakers, rather than audience, had the most agency in communicating widely. The Transactional Model, introduced by Barnlund in 1970, recognized the subtlety of complex interactions where sender and receiver continuously decipher each other’s language. It also accounts for the constant presence of nonverbals including facial expressions and body language within the context, field of experiences, and relational dimensions present in the sender and receiver exchange. Table 1.1 provides a summary of these models.

Table 1.1: The Evolution of Communication Models in the Last Century

|

Model |

Description |

Characteristics |

|

Linear Model (1949) (Shannon and Weaver) |

The sender is central; communication flows one way from sender to receiver. Model heads one way, regardless of audience, audience perception, or audience reaction. |

Sender-centric One-way flow Simplicity |

|

Interactive Model (1954) (Osgood and Schramm) |

Acknowledges the receiver but lacks depth in understanding verbal and nonverbal cues. Communication is almost like synchronized, sequential dance moves with one participant being studied at a time. |

Sender and receiver interaction Verbal and nonverbal nuances Busy model |

|

Transactional Model (1970) (Barnlund) |

Recognizes dynamic interplay between sender and receiver. This model allows for a complete and nearly infinite process where sender and receiver of communication continuously evaluate verbal and nonverbals of each other. |

Mutual influence Continuous deciphering Nonverbals matter (facial expressions, body language, context) |

![]() Explore the Transactional Model on your own through the link found in the following resource. Communication coach Alexander Lyon shares a good introduction to better understand the communication process and learn more about the Transactional Model. As you consider the video, think about the relational dimensions and fields of experience in your regular communication at home, school, or work. Lyon, A. (2017, Sep 4). Transactional Model of Communication. Communication Coach. [Video]. YouTube.

Explore the Transactional Model on your own through the link found in the following resource. Communication coach Alexander Lyon shares a good introduction to better understand the communication process and learn more about the Transactional Model. As you consider the video, think about the relational dimensions and fields of experience in your regular communication at home, school, or work. Lyon, A. (2017, Sep 4). Transactional Model of Communication. Communication Coach. [Video]. YouTube.

Step-by-Step Instructions for Considering the Transactional Model of Communication

Step-by-Step Instructions for Considering the Transactional Model of Communication

Keep the following in mind while receiving messages to ensure you capture all the information being communicated intentionally and unintentionally:

- Observe: Note how the sender enters the conversation. What was their body language before communicating? What nonverbals were displayed during their message, after they were done, and while you were responding? Be aware of the context, field of experiences, and relational dimensions present in this channel.

- Listen: What is the person saying? How are they saying it? What do they intend for you to hear?

- Confirm: As needed, confirm the message you believe you are receiving to get greater clarification and, in some cases, to validate what they are telling you. Remember: Your own nonverbals such as nodding and looking intently show signs of interest.

- Note: Is there information they are not sharing? Do you need further information before responding? Before asking, it may be good to ask if they are open to your questions.

- Respond: Once satisfied with your understanding of what they are saying and after gaining additional information, if necessary, is it important to respond immediately? While responding, observe nonverbals and listen for affirmation or questions they may have for you.

Please note this process may happen quickly, interchangeably, and with several layers of sender and receiver feedback.

Before turning away from the transactional communication model, it is important to note that all communication, including the complex deciphering of the sender and receiver process, can be overwhelming and not perfect. All communicators need to give themselves permission to unpack these experiences through trial-and-error learning.

Exploring Cognitive Overload and the Buffet Effect

Christoper Schimming at the Mayo Clinic (2022) formally identifies “noise” as information overload. They indicate the phenomenon, which they call cognitive overload, occurs when the brain has too much information to process. Cognitive overload can be overwhelming to the individual experiencing the phenomenon. It can also lead to a point of paralysis where the receiver chooses not to do anything, incapable of deciphering or acting upon the information received. The situation is compounded if the person is relied upon to make a judgment based on the information. It is easy for both parties to become frustrated. This condition is exacerbated by constant sources of data and information through television or streaming shows, movies, social media, and the internet, to name a few. As teachers, your authors have even noticed that our lectures and exercises compete with iPhone text messages and emails. It’s important to fully understand the symptomatic reactions to cognitive overload and their effects as detailed in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Reactions to Cognitive Overload With Explanations

|

Reactions to Cognitive Overload |

Reaction Explained |

|

Paralysis |

You are unable to deal with the topic or information because it appears more complex than manageable. |

|

Anger |

If information is not consistent with what you know or feel, you may get angry as your beliefs, knowledge, or experiences get challenged. Repeated efforts to address an issue with this information may make it worse. |

|

Passivity |

You decide to go along because forming an opinion on the topic may be too overwhelming. |

|

Understanding |

You may process information by relying on the knowledge or input of others who are more trusted. You may also rely on your trusted ways of learning to slowly gain the knowledge you need to arrive at an opinion or a decision. |

Finally, when considering cognitive overload, we should also consider that many senders have arrived equipped with information-heavy messages filled with data, graphs, and exuberant amounts of PowerPoint slides due to what we call the Buffet Effect. If you have ever enjoyed the plentiful choices of an elaborate buffet, you know that at the onset, the choices seem irresistible and delicious. However, those of us who decided to try many (or even all those choices) know it is impossible to do so without feeling the aftereffects of our choices. In such a moment, the food once considered for its nutrition and sustenance has instead become something that causes indigestion, sleepiness, or lethargy. Simply put, we don’t need all those buffet choices. Instead, we need food items that will give us the requisite calories, energy, and ability to conquer our day.

Applying the Buffet Effect to communication, senders preparing their messages may have adopted a similar approach as the restaurant owners hosting a lavish buffet, although with less appeal for the receivers. Instead of making strategic choices about evidence to support their claims, senders may have decided to add a bit of everything to their argument. They may include elements of excessive background along with undecipherable and endless graphs and statistics. If given 15 minutes to talk, they may have used every minute and still not gotten their information across. We can easily see how the Buffet Effect, reinforced by access to information, can lead to cognitive overload.

1.1 Exercise 2: Monitoring the Buffet Effect in Communication Experiences

Learning Objective #2—Describe the various aspects of audience perception and of speaker and message, and conduct key analysis before creating or delivering a presentation

Consider a time when the Buffet Effect happened in your own communication experience. You can consider this cognitive overload from the point of the sender or receiver. How did you feel during this experience? Was this feeling the sender’s intention?

Consider a time when the Buffet Effect happened in your own communication experience. You can consider this cognitive overload from the point of the sender or receiver. How did you feel during this experience? Was this feeling the sender’s intention?

The Use of Figurative Language

You’ve probably noticed we use figurative language in this text. As two teachers authoring a text on data visualization and storytelling, this was intentional. A term like Buffet Effect, a metaphor for how cognitive overload can affect messages, is an example of figurative language. As communicators and teachers, we see this as a valuable resource. Beyond metaphor, we can include simile, personification, and hyperbole as powerful language tools.

![]() To learn more about how to power up your audience-centered language, check out DifferenceBetween.com, where expert authors tackle a variety of subjects.Sethmini. (2021, June 18). Difference Between Simile Metaphor Personification and Hyperbole. https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-simile-metaphor-personification-and-hyperbole/

To learn more about how to power up your audience-centered language, check out DifferenceBetween.com, where expert authors tackle a variety of subjects.Sethmini. (2021, June 18). Difference Between Simile Metaphor Personification and Hyperbole. https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-simile-metaphor-personification-and-hyperbole/

Before turning away from the Buffet Effect, it’s important to note that practices that offer too much information can be the exception instead of the rule. In this text, we will talk about different types of evidence, tools, tips, and best practices to effectively reach your audience. The remainder of this chapter will explore strong persuasive tips and storytelling to frame the reasoning behind the message. Before doing that, however, let’s turn next to audience analysis.

1.1 Self-Assessment: Buffet Effect

Learning Objective #1—Identify communication models that predict connection and identification between speaker and audience

![]() Look at your calendar for the last three days. Make a list of all the meetings you had and think about the communication in those meetings. Particularly consider the appeals and requests from senders and receivers. Place an × next to those meetings where the cognitive overload or Buffet Effect was evident. If the Buffet Effect was not present, place a + next to the meeting. Then for each × and + meeting, describe the following information.

Look at your calendar for the last three days. Make a list of all the meetings you had and think about the communication in those meetings. Particularly consider the appeals and requests from senders and receivers. Place an × next to those meetings where the cognitive overload or Buffet Effect was evident. If the Buffet Effect was not present, place a + next to the meeting. Then for each × and + meeting, describe the following information.

For × meetings, what went wrong? What did you not understand? What should the sender have done differently?

For + meetings, what went well? What was the sender asking of you? What did the sender do to be so effective?

1.2 Exploring and Unpacking Audience Perceptions

It all starts with being curious and humble: putting yourself in the shoes of your audience.

—Samara Johansson, strategic marketing specialist

Managing Fear Among Unknown Audience Members

In this section we explore the audience and how to gain information about them. The audience can often be the most fearful aspect of our communication experience. After all, most of the appeals we make as senders involve leaving the decision-making strictly in their hands. While most of us have a fear of the unknown, we often have a greater fear of how an audience will react to anything we are offering. We might ask: Will they like me? Am I dressed appropriately? What do they know about the subject I am discussing? Will they accept the information I provide? Will someone ask a hard question? Of course, it is perfectly human for every communicator to face dwindling confidence levels and feel a tinge of panic by simply considering these questions.

This fear of public speaking may include fear of being seen as nervous, anxiety about panic setting in, toxic perfectionism, and terror at the thought of going forth on your own. It could also include defensive thinking and behavior, detachment from thoughts and feelings, and even rationalizing a career or class change to justify not speaking in public (SocialAnxiety.com, 2021).

Fear of public speaking can happen to anyone when not managed. A notorious incident took place when Michael Bay, a successful movie producer and director, left the stage at a Samsung product rollout after a teleprompter failed. You can watch the video and consider what went wrong, how you might have reacted in that same situation, and obvious details that Michael missed in the flurry of the moment. How could this difficult experience have been different?

![]() CNET. (2014, Jan. 6). Michael Bay quits Samsung’s press conference. [Video]. YouTube.

CNET. (2014, Jan. 6). Michael Bay quits Samsung’s press conference. [Video]. YouTube.

Regaining Confidence Through an Affirming Set of Guides

Many individuals walk into communication experiences with a variety of baggage. After years of working with students who were struggling with confidence, we came up with four recommendations to help communicators. Many of those students were overwhelmed by anxiety, which never permitted them to consider their audiences. We hope this confidence-affirming guide as shown in Figure 1.1 helps you too as you prepare for audience analysis.

Figure 1.1—Every Communicator’s Guide to Better Confidence

![]() To get practice speaking in front of others, consider visiting a Toastmasters International Club. Toastmasters is an organization that helps individuals develop communication skills and overcome public speaking anxiety through a variety of tools and techniques in a safe learning environment. To find a club, visit https://www.toastmasters.org/Find-a-Club/.

To get practice speaking in front of others, consider visiting a Toastmasters International Club. Toastmasters is an organization that helps individuals develop communication skills and overcome public speaking anxiety through a variety of tools and techniques in a safe learning environment. To find a club, visit https://www.toastmasters.org/Find-a-Club/.

Step-by-Step Instructions to Take Inventory of Your Assets

Step-by-Step Instructions to Take Inventory of Your Assets

A healthy way to see the tremendous gifts you bring to any organization or moment is to look exhaustively at the various things you’ve accomplished. Use this exercise to develop those skills by which you can teach others and share with audiences.

List 3 examples of experiences you have in the following categories:

- Work (professional): Just as it sounds. What work activities bring you to this moment?

- Work (formative): These jobs may not be your current professional trajectory, but they made you who you are as you were developing into the professional you’ve become.

- Education: Which key learning experiences played a role in your development?

- Home internship: Think through the roles in the family business, chores, duties, or other activities.

- Training: Beyond education or experience, did you have specific training that equipped you for what you presently do?

- The good: Think about the other things that have happened to you, personally or professionally, that were positive.

- The bad (and ugly): These were negative at the time, but they are now part of your story, and you learned from them.

- I can . . . ! It could be a hobby, trait, skill, or interest you have that is awesome. When you do it, you do it well.

Beyond Fear: Learning About Different Types of Audience Members

Let’s explore some special considerations regarding audience types. We all walk into a situation with life experiences that guide us, inform our cultural experiences and judgments, and assist us as we meet new people and make sense of those meetings. Rhetorical scholar Kenneth Burke termed such moments and judgments, particularly as they engage our persuasive processes, as identification. Identification is the way that communicators relate with each other based on background, differences, tone, speaking styles, and so on. While this identification might sound like individuals will only relate to those who have similar experiences, this is just a starting point. As we meet more people and learn of their differences, our identification bubble expands through common ground.

![]() Unpacking Kenneth Burke’s theory on identification can take some time, but this resource can help. The process also requires self-awareness of our own characteristics and identities. Once we become more aware, we can find common ground with our audiences and will be in better shape as communicators.Writing with Andrew. (2021, Oct 4). Finding Common Ground With Identification | Kenneth Burke’s Rhetoric of Motives. [Video]. YouTube.

Unpacking Kenneth Burke’s theory on identification can take some time, but this resource can help. The process also requires self-awareness of our own characteristics and identities. Once we become more aware, we can find common ground with our audiences and will be in better shape as communicators.Writing with Andrew. (2021, Oct 4). Finding Common Ground With Identification | Kenneth Burke’s Rhetoric of Motives. [Video]. YouTube.

A key part of that identification process is recognizing the differences inherent in all audiences. Specifically, we must consider the audience’s demographic and psychographic aspects. According to Land et al. (2020), demographics consist of the characteristics of a population. Psychographics consist of a buyer’s habits, hobbies, spending habits, and values. Both demographics and psychographics are key to our preparation and can be predictive of an audience member’s openness to our message. That said, it is imperative to remember that audiences vary despite common characteristics. Approaching all groups as if they are the same can lead to unfair biases that may be off-putting to audience members. While keeping in mind demographics, psychographics, and maintaining flexibility in our approaches, let’s list key aspects of each, as shown in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Demographic and Psychographic Aspects

|

Demographics |

Psychographics |

|

✓Age |

✓Values and Beliefs |

|

✓Gender |

✓Attitudes |

|

✓Economic Background |

✓Political Affiliation |

|

✓Ethnicity |

✓Interests |

|

✓Location |

✓Personality Traits |

|

✓Education |

✓Lifestyle |

![]() Learn more about demographics and psychographics in this quick video. As you listen to John Fallon, note how diverse and expansive your audiences can be while considering these aspects.Fallon, J. (2012, Aug 3). Audience Demographics and Psychographics. [Video]. YouTube.

Learn more about demographics and psychographics in this quick video. As you listen to John Fallon, note how diverse and expansive your audiences can be while considering these aspects.Fallon, J. (2012, Aug 3). Audience Demographics and Psychographics. [Video]. YouTube.

1.2 Exercise 1: Explore Demographics and Psychographics of Audience Members

Learning Objective #2—Describe the various aspects of audience perception, of speaker and message, and conduct key analysis before creating or delivering a presentation

Consider the list of demographics and psychographics. What are some of the ways that communicators reach you via these important and powerful categories? What are things they ignore? Document both and draft out the following alongside each identified demographic and psychographic miss: What opportunities were lost, what appeal could have been added, and what are the repercussions of the miss?

Consider the list of demographics and psychographics. What are some of the ways that communicators reach you via these important and powerful categories? What are things they ignore? Document both and draft out the following alongside each identified demographic and psychographic miss: What opportunities were lost, what appeal could have been added, and what are the repercussions of the miss?

Diversity and Bias

As you may be starting to understand via this chapter and through your own experiences, audiences are all different, and in any consideration, this is a wonderful thing. As a popular colleague of ours often says, “different” does not mean deficient—it just means different. Recognizing diversity, otherwise known as our differences among various demographic and psychographic traits, can be powerful for communicators. Even more impactful is when we assemble and recognize diverse teams or unite them through the communication we offer. In fact, Forbes (2021) indicated that simply boosting diversity in our workplaces can increase creativity and innovation, create greater organizational opportunities for professionals, and lead to better overall decision-making.

We also must recognize the bias that influences our perspectives, practices, and resulting modes of communication. Bias is a prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared to another, usually in a way that can impair or eliminate fairness. For instance, as midwestern university authors working at global institutions, we are likely to have differing perceptions from the global gathering of students and faculty we regularly meet. This can include our concept of time, customs such as greetings, or how we build trust.

The important first step in confronting bias is recognizing that we all have certain predilections that favor certain cultural experiences. If that bias remains unchecked, it can be detrimental to how we connect and communicate with others. In Chapter 8, we will explore to a greater extent how we communicate across gaps to reach diverse audiences, including those of different genders, cultures, and generational demographics.

In the meantime, keep reflecting on the fact that bias is real, and account for it. Often the term bias raises concerns for individuals. That said, by considering how bias (e.g., our natural experiences or cultural backgrounds) may influence our communication, we prepare for healthy audience interactions.

![]() In this section we discussed bias that can account for an individual’s perception, but there is also research bias. The University of Wisconsin–Green Bay Libraries produced a great online resource to get you thinking about research bias. Check it out and see why bias is such a problem in our communication and research, as it undermines our arguments, research, and work when left unchecked. University of Wisconsin–Green Bay Libraries—Research Guides. (2024, Jan 16). Identifying Bias. https://library.uwgb.edu/bias

In this section we discussed bias that can account for an individual’s perception, but there is also research bias. The University of Wisconsin–Green Bay Libraries produced a great online resource to get you thinking about research bias. Check it out and see why bias is such a problem in our communication and research, as it undermines our arguments, research, and work when left unchecked. University of Wisconsin–Green Bay Libraries—Research Guides. (2024, Jan 16). Identifying Bias. https://library.uwgb.edu/bias

Conducting Audience Analysis Toward Successful Communication

Now that we have accounted for bias while considering the demographics and psychographics of diverse audiences, let’s determine how to move forward with our messages. Peter Cardon (2021), an expert on effective business communication, wrote about key components for audience analysis. First, as communicators looking to have influence, we should identify any benefits our message contains for audience members. Similarly, we also must recognize any constraints posed by our communication within the existing system structure. The term system structure refers to the overall organization and interconnections within a communication system. It includes how different components interact and influence the flow of information. A good example of a constraint is the limitation on the number of characters when writing a tweet.

Next, what are the recipients’ values and priorities? These key determiners help us fiercely home in on our audience. After values and priorities are analyzed, we should review our own credibility on the subject. Remember, we often undersell our abilities, experience, and knowledge in this area, and this can be a core mistake of an otherwise strong message. We should also estimate and anticipate audience reactions to our message. Remember that communication is an imprecise tool; however, anticipating a response that has not yet been received can lead to a better understanding of your audience. Finally, we should simultaneously keep secondary audiences in mind as we prepare our message. Secondary audiences may not be the front line for our message, but they certainly factor into how decisions are made at multiple levels.

Now that you know the initial planning steps for your message, how often have you used audience analysis in your current strategy? It is common for many communicators to do one or more of these steps. It is also common that many otherwise highly skilled and talented individuals do none. How do you think their communication improves by performing this analysis?

![]() Custom-tailoring your public speaking. Communication coach Alexander Lyon discusses tips for prioritizing the audience and why.Lyon, A. (2022, Feb 14). How to Analyze an Audience for Public Speaking. Communication Coach Alexander Lyon. [Video]. YouTube.

Custom-tailoring your public speaking. Communication coach Alexander Lyon discusses tips for prioritizing the audience and why.Lyon, A. (2022, Feb 14). How to Analyze an Audience for Public Speaking. Communication Coach Alexander Lyon. [Video]. YouTube.

Beyond the audience analysis, there are specific steps to ensure our message resonates with our audience. Rather than relying on guesswork, we can directly investigate opinions. Consider any one or more of the steps in Exhibit 1.1 for potential audience analysis tools.

Exhibit 1.1—Potential Tools for Audience Analysis

✓What information is readily available? Find out via

-

- internet

- social media accounts

- current audience members you know and trust who will be most effective

✓If applicable, ask the organizer.

-

- What does the group want to know?

- What is the physical setup where you’ll be communicating and expectations?

- If appropriate, where has past communication gone wrong?

- Are there other organizational culture components that are important to them?

✓Survey the crowd.

-

- What do they know?

- What would they like to know?

- What do they expect to know when you are done?

✓Utilize a focus group.

-

- Create or survey a similar demographic or psychographic group.

- If the information is case-sensitive, try some broad ideas.

- Consider this formally and informally to scale.

Audience analysis can be a complicated endeavor. As always, no one may do it identically or perfectly for every situation. That said, diligence in seeking information about your audience, as well as their interests, can be highly beneficial to a communicator. Managing our confidence, accounting for audience diversity, and recognizing bias, maximizes your preparation skills.

1.2 Self-Assessment: Audience Analysis

Learning Objective #2—Describe the various aspects of audience perception and of speaker and message, and conduct key analysis before creating or delivering a presentation

![]() Applying what you know, identify opportunities for improvement in the following scenario: Kyla arrived where she was giving a presentation. She had made sure to arrive early, not knowing anything about the audience and wanting to get a look five minutes before she was due to talk to the community group. As she looked around, she noticed that the location was not a building but rather a park. Would this space accommodate her 30-slide PowerPoint deck or have the technology needed to view the slides? She nervously approached the group and saw an overwhelming number of senior audience members gathering in the shelter house. Kyla, a community activist, had been arguing for months that Congress should lower social security payouts to balance the budget. Now she wondered if that subject was appropriate for this audience. . . .

Applying what you know, identify opportunities for improvement in the following scenario: Kyla arrived where she was giving a presentation. She had made sure to arrive early, not knowing anything about the audience and wanting to get a look five minutes before she was due to talk to the community group. As she looked around, she noticed that the location was not a building but rather a park. Would this space accommodate her 30-slide PowerPoint deck or have the technology needed to view the slides? She nervously approached the group and saw an overwhelming number of senior audience members gathering in the shelter house. Kyla, a community activist, had been arguing for months that Congress should lower social security payouts to balance the budget. Now she wondered if that subject was appropriate for this audience. . . .

1.3 Powerful and Influential Presentations

Words have power.

—Seanan McGuire, author

Seeing the Infiniteness of Sources for Our Persuasive Influence

Anytime you observe the word influence, we encourage you to consider the word persuasion. Influence is the capacity to affect the character, development, or behavior of someone or something, or the effect itself. When we use influence, we persuade. The definition of persuasion points to the process in which one or more persons try to influence another person or group’s behaviors. Some teaching scholars make the argument that both influence and persuasion can be separated from other forms of communication that may take on more objective natures void of subjectivity. While we appreciate the sentiment, we would point out that selecting objective communication involves subjectivity that suggests influence and persuasion.

Textbooks, including this one, are arranged by decisions about what information to include/exclude and how it should be portrayed. In our classrooms, our campuses have made very subjective decisions about what a higher education classroom should look like, just as teachers and students alike have decided how best to appear, dress, and be present in such an environment. On the way to the classroom, we are bombarded by persuasion in advertisements, podcasts, and social media feeds that portray a life those posting wish it to be displayed. Everything, as it turns out, knowingly and unknowingly, has some element of persuasion. With this notion in mind, we should seek to make our influence impactful, dynamic, and with the most efficient communication possible. In the following section, we will discuss potential structures to format influential, persuasive, and audience-centered presentations. We will also discuss learning tools for that process, including presentation software to augment our argument.

1.3 Exercise 1: Identifying Persuasion in Our Everyday Life

Learning Objective #3—Flex between direct and indirect persuasion models to deliver influential communication

Be mindful of the persuasion in your life. We defined persuasion in the opening of Section 1.3. With that in mind, list the top 10 things that have persuaded you in the last 24 hours. What made your list? What does that reveal about you as an audience member? Was that persuasion effective? Was there anything you now recognize as subtle persuasion?

Be mindful of the persuasion in your life. We defined persuasion in the opening of Section 1.3. With that in mind, list the top 10 things that have persuaded you in the last 24 hours. What made your list? What does that reveal about you as an audience member? Was that persuasion effective? Was there anything you now recognize as subtle persuasion?

Leading to Direct and Indirect Persuasion

We discussed ethos, pathos, and logos at the start of our chapter. Ethos refers to the credible speaker while pathos refers to the important emotional connection between sender and receiver in the communication process. Logos, which consists of the evidence we assemble to support our argument, also includes the way we construct that message. Constructing a message effectively speaks to the very influence and persuasion we referred to in this chapter.

Ethos, pathos, and logos become powerful tools to account for in an argument. However, for a communicator, it is important to note that simply including elements of those three is not necessarily the most effective way to reach an audience. Communicators should also understand the varying degrees ethos, pathos, and logos can be used depending on the audience. For instance, how we present our ethos (credibility) will be different depending on the receiver. Our pathos (emotional connection) may center on shared values in a professional setting whereas personal pathos might center on family bonds. Certain groups, such as cultures that value relationships and trust in decision-making, may not be as receptive to evidence at the onset of a presentation before establishing a relationship.

In the case of transactional communication, flexibility is key to prioritizing the audience. Some audiences need a direct approach when asked to act. Direct persuasive approaches, where the solution or answer is upfront, are often effective in the United States with audiences that are familiar with U.S. business culture. Other audiences, such as those in Chinese organizations, may find direct approaches to be off-putting and unsettling. Such audiences will likely prefer indirect persuasive approaches that reflect their processes (e.g., learning background, time to consider potential solutions, followed by determining logical next steps).

We will talk more about audience and cultural differences in Chapter 8. For now, let’s examine direct and indirect approaches to persuasion to gain familiarity with two powerful techniques. As always, keep in mind that no uniform method is a sure bet for all audiences. Instead, take these tools and determine the best way to craft your communication.

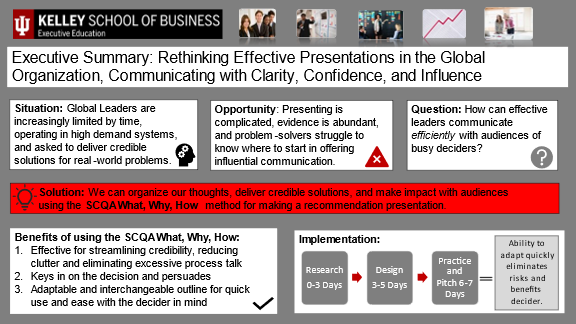

Direct Persuasion in Action With Busy Deciders

Direct persuasive approaches work well when audience members want their answers up front. We often call these audience members deciders. These leaders may fully understand the problem and the solution but have not yet committed to a specific change.

Business scholar Barbara Minto (2021) developed a way to reach such deciders in a highly effective way while training new sales associates; she called it the Pyramid Principle. Its adaptation, naming, and usage have been commonplace in business communication. The process involves an introduction of the problem called the Situation, Complication, Question, and Answer, or SCQA. It is followed by the What, Why, and How. Exhibit 1.2 better explains the function of this adapted version of the Pyramid Principle.

Exhibit 1.2—Adapted Pyramid Principle

Adapted Pyramid Principle

Introduction

Situation (S): Set the scene for the present circumstances.

Complication (C): Name the problem or opportunity that needs to be fixed.

Question (Q): Pose the question being asked for the problem that sets up the solution.

Answer (A): Briefly provide the named solution you will explain in the body of the presentation.

The SCQA should consist of no more than 20% of the total presentation. We don’t want to dwell on a background the audience of deciders already knows.

Body

- What: Expand upon an answer or idea. Name the component parts the audience needs to understand.

- Name three whys to support adopting the “what.” Keep at least one financial in nature, particularly in business.

- Describe how to make the solution happen.

- Discuss the timeline for completion. With visuals, this can be very appealing.

- State the risks to adopting your solution, then discuss how those risks could be mitigated.

The Pyramid Principle can be hard to decipher for eager audiences. Exhibit 1.3 showcases an example of how the pyramid components work in practice.

Exhibit 1.3—Showcasing the SCQA Structure

Learn about Barbara Minto’s background, motivations, and the experience that lead to a breakthrough in practical communication. McKinsey Alumni. (2024). Barbara Minto: “MECE: I invented it, so I get to say how to pronounce it.” Alumni News. https://www.mckinsey.com/alumni/news-and-events/global-news/alumni-news/barbara-minto-mece-i-invented-it-so-i-get-to-say-how-to-pronounce-it

1.3 Exercise 2: Implementing a Direct Persuasive Model

Learning Objective #3—Flex between direct and indirect persuasion models to deliver influential communication

Putting the Pyramid Principle into Practice. Review the Bailey’s Orchard case scenario using the SCQA What, Why, How method. You may approach the case as any relevant convincer to any relevant decider. Keep in mind that solutions to the scenario may seem obvious to you but unclear to others, hence the power of using a direct persuasion tool.

Putting the Pyramid Principle into Practice. Review the Bailey’s Orchard case scenario using the SCQA What, Why, How method. You may approach the case as any relevant convincer to any relevant decider. Keep in mind that solutions to the scenario may seem obvious to you but unclear to others, hence the power of using a direct persuasion tool.

Case Scenario—Bailey’s Orchard

Bailey’s Orchard is a small produce store on the outskirts of town that features seasonal goods, bakery items, and home-craft specialties produced by local artisans. The store, in operation since 1947, is located five miles from downtown Harrison City and seven miles from a thriving university. Bailey’s is rooted in their traditional way of doing business and just recently got an electronic cash register in addition to their pen and paper inventory system. Bailey’s does not use social media and certainly does not advertise. In fact, 80% of their business comes from repeat customers living in the community surrounding the store. Their biggest competitor, Taylor’s Pumpkins and Specialties, is located 15 miles from Harrison City and 17 miles from the university, with 55% of their yearly sales coming from university students buying pumpkins alone. The manager of Bailey’s is Mariah, and she often closes a quiet shop while wondering if they could be doing something more. . . .

Indirect Persuasion and Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Now that we have addressed direct persuasive approaches, we should also consider indirect persuasion and how it applies to our argument. Indirect persuasion is appropriate for audiences who may already be familiar with the topic but have not yet made up their mind. It also resonates with potential allies toward a solution or open-minded individuals. Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is a method of persuasion and is based on Dr. Allan Monroe’s studies related to psychology. Monroe made the case that humans, when presented with a dilemma, are inclined to respond to the need. His sequence allows the author to offer a solution after presenting the problem. It also offers communicators a complementary vision of what they present.

Exhibit 1.4—Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Attention: In this phase, we connect with the audience. This might be a story, example, rhetorical question, startling statistic, and so on that reels the audience in. The important thing is to get their attention.

Need: This is the problem that frames our sequence. What is the thing that needs to be solved? This should be thorough.

Satisfaction: Monroe was careful not to call this solution, though that is just what it does. Satisfaction is the sender’s solution to remedy the problem and take the burden away, therefore satisfying the need.

Visualization: This crucial step allows the audience to see what life will look like when the change is adopted. It allows them to dream and visualize the solution.

Action: The last step is to give the audience the crucial steps to get started.

![]() Monroe’s Motivated Sequence has many uses in persuasion and can take on many different forms. Anyone watching commercials may have noticed its characteristics of quick and repetitive use, such as here with Ruby Space Triangles. Global Shop Direct. (2023, Feb 15). RUBY Space Triangles—As Seen on TV. [Video]. YouTube.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence has many uses in persuasion and can take on many different forms. Anyone watching commercials may have noticed its characteristics of quick and repetitive use, such as here with Ruby Space Triangles. Global Shop Direct. (2023, Feb 15). RUBY Space Triangles—As Seen on TV. [Video]. YouTube.

![]() It can also be seen in this more formal presentation on cell phone use by Comm Studies.Comm Studies. (2020, Nov 30). Persuasive Speech: Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. [Video]. YouTube.

It can also be seen in this more formal presentation on cell phone use by Comm Studies.Comm Studies. (2020, Nov 30). Persuasive Speech: Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. [Video]. YouTube.

Persuading and Influencing Through Presentation Software

Finally, having the proper means to display the information for our arguments, whether that be through direct or indirect persuasion, is a fundamental responsibility of the author. This means we are duty-bound as communicators to support our message with appropriate visualization. While this text will refer to data visualization throughout the remaining chapters, it’s important to start by understanding what that means within presentation software. Presentation software will allow you to display your ideas and persuasion in a convenient and organized way.

We’ve compiled a list of presentation software for you to consider. This list is not exhaustive; you may have your favorite. As visualization designers, we would note two things. First, we recognize that some software is more common to us because we became familiar with it through its availability, learning, and organizational use. Second, we should all be cognizant that trying new software may be beneficial to slide preparation and design. Table 1.4 shows only a partial list!

Table 1.4: Slide Preparation—Host of Choices

|

Visme |

Prezi |

Keynote |

Google Slides |

|

Microsoft PowerPoint |

Ludas |

Slides |

Slidebean |

|

Beautiful.ai |

Genially |

Canva |

Venngage |

|

Flowvella |

Haiku Deck |

Microsoft Sway |

Zoho Show |

It is important to note that for your presentation software to be effective, it must work for you. Its usage should be convenient and efficient, supportive of your ideas, and not distracting. Beyond this, you should consider what we hold as the primary rule of slide design: Everything you create should strive to be consistent aesthetically with the culture of your audience and their visual consumption. Essentially, if it works well for the audience, the design works well for your needs.

Strategies for Effective Slide Visuals

First, you should outline your design before creating slides. This ensures that the number of slides is consistent with your time limits as a presenter. Next, your slide deck should have a title slide that states the name of the presentation along with your own. It can also offer imagery that supports the idea you are presenting. Consider adding a visual agenda bar that allows audience members to see your place in the presentation as it advances. This reminds audience members of your place in the presentation, what has been covered, and what will be covered next.

Visual animations can be appealing, and they lend support to your idea—be sure they do not distract from your presentation. Color templates and fonts should be consistent, and where possible, add claim headings at the top that summarize each slide. Remember to only display information relevant to the presentation in the most effective way. Too much or too little can be distracting. Also, information that does not need to be in the presentation but could be supportive during questions may be placed in appendix slides at the end of your deck. Finally, if you have a company logo, you could consider placing it at the top right of your slides throughout the deck. Remember, accommodating the audience means providing the most important parts for their consideration.

![]() PowerPoint Storytelling using SCQA. Learn how to create compelling presentations. Analyst Academy. (2021, Nov 17). PowerPoint Storytelling: How McKinsey, Bain and BCG Create Compelling Presentations. [Video]. YouTube.

PowerPoint Storytelling using SCQA. Learn how to create compelling presentations. Analyst Academy. (2021, Nov 17). PowerPoint Storytelling: How McKinsey, Bain and BCG Create Compelling Presentations. [Video]. YouTube.

![]() Watch a funny video from Don McMillan. This video is a classic on how slide design first emerged and was abused by many presenters. Enjoy this while also learning a few lessons on what might annoy your audiences. McMillan, D. (2009, Nov 9). Life After Death by PowerPoint (Corporate Comedy Video). [Video]. YouTube.

Watch a funny video from Don McMillan. This video is a classic on how slide design first emerged and was abused by many presenters. Enjoy this while also learning a few lessons on what might annoy your audiences. McMillan, D. (2009, Nov 9). Life After Death by PowerPoint (Corporate Comedy Video). [Video]. YouTube.

1.3 Self-Assessment: Presentations

Learning Objective #2—Describe the various aspects of audience perception, of speaker and message, and conduct key analysis before creating or delivering a presentation

![]() Applying what you know, complete the following statement.

Applying what you know, complete the following statement.

1.4 The Power of Storytelling

Story is probably the most fundamental and important element of entertainment in the world. It’s a basic building block. It comes into play in virtually every creative medium. Storytelling is the oldest profession. Don’t believe what you’ve heard. People were telling lies long before another business was invented.

—Jim Shooter, former editor-in-chief, Marvel and Valiant Comics

Rethinking Our Communication for the Frame and Narrative of Storytelling

Once upon a time there were two teachers who decided to write a textbook about data visualization and storytelling. . . . Sound familiar to you? It is because we all have been absorbing stories from the very start of our lives. As authors, we have found that whenever we discuss storytelling, certain audience members start to get a little nervous. Some business leaders, for example, don’t see a place for storytelling in their vast networks of official decision-making where bulky slide decks and Excel spreadsheets abound. Others see storytelling as something reserved for personal time and not at all part of their communication.

We push back on the notion that storytelling doesn’t belong in communication. In fact, we think it is more effective and supplies both the shared sense-making and underlying communication of all that we do. As an example, the same business that denies the use of storytelling may simultaneously pay millions of dollars for advertising in commercials that feature entities and characters that are fictitious. The breakroom of the organization may also contain a few people making sense of the new addition to the company handbook. We can almost hear Lisa explaining to Kim what happened to Jerry at last year’s holiday party that prompted the handbook’s update. The same employees will arrive at work fresh from listening to story-filled ballads in music, podcasts, news, and biographies. They most assuredly spent the night before binge-watching streaming shows on cable, television, and smartphones. Perhaps they even curled up with a good book. Storytelling is occurring for nearly everyone. The question remains how we use it for ourselves.

Think about your own last 24 hours of story consumption. List all the forms you engaged in (biographies, books, gossip, movies, music, podcasts, poems, streaming shows, and workplace conversations).

For our purposes, storytelling and narrative become fluid terms in practice that we place under a banner of storytelling. Storytelling describes processes by which communicators account for past experiences, support ideas with framing, offer certain dream-casting visions for the future, justify values through real-world or fictitious examples, and discuss leadership through verbal or written artifacts that describe those who have gone before, lead today, or are yet to come (D’Abate & Alpert, 2017, Hansen, 2012). Further, we see storytelling as relating and meaning-making. This supports the work of narrative scholar Walter Fisher (1985), who first crafted this notion that stories connect the sender and receiver. In summary, our influence, arguments, and ideas are a form of storytelling too. This doesn’t mean we will replace our Excel sheets with “Once upon a time . . . ,” but it does mean we will examine how storytelling may help us reach audiences.

Freytag’s Pyramid for Storytelling

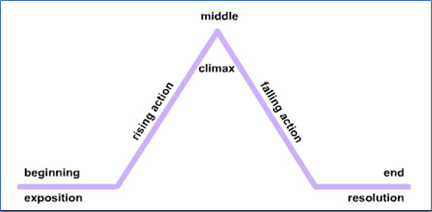

The fundamentals of storytelling are made more common to us by our constant absorption of them on a daily basis. Aristotle himself noted that a story has a beginning, middle, and end. Later, Gustave Freytag, a German novelist and playwright, developed a pyramid in the late 1800s that explains the familiar action of the story. Called Freytag’s Pyramid, it has since been adapted to describe the familiar patterns (see Figure 1.2) we see in many stories to this day. In the beginning, we have the exposition or starting point of the story that sets the scene and establishes the characters. Next, the rising action builds up the key moments in which the protagonist must face a crucial moment, otherwise known as the climax or turning point. Next, the falling action ensues, which often contains the winding down of drama following the climax as characters and circumstances fall into their new places. The resolution or denouement is considered the end, where events conclude, takeaways and lessons are applied, and meaning is derived from the action.

Figure 1.2—Freytag’s Pyramid for Storytelling

![]() See Freytag’s Pyramid in action via a familiar children’s story. You can quickly see this very common framework represented in simple stories. After you are done, think through the last movie you saw. Did it follow Freytag’s Pyramid?Tolzin, T. (2015, Jun 8). Freytag’s Pyramid. [Video]. YouTube.

See Freytag’s Pyramid in action via a familiar children’s story. You can quickly see this very common framework represented in simple stories. After you are done, think through the last movie you saw. Did it follow Freytag’s Pyramid?Tolzin, T. (2015, Jun 8). Freytag’s Pyramid. [Video]. YouTube.

Introducing Narratives to Frame Powerful Messages

Establishing the building blocks of storytelling alone does not help us connect our communication with storytelling. In fact, there are times we might be called to utilize only a part of a story to convey the idea of our message. To discuss this further, let’s examine narratives as described by Fisher (1985). Narratives, known as Narrative Paradigm Theory, operate from the basis that every speaker, both knowing and unknowing, is a storyteller and that we connect to each other via these devices often and openly. In fact, as authors, we encourage students and interested practitioners to examine how often others communicate using stories, imagery, descriptive narratives, or even looser examples of figurative language such as metaphor or simile. Example: “I am so hungry, I could eat a horse!” While most audience members doubt that we want to eat a horse when we make such a declarative statement, they do understand the implied meaning in our message.

Seven Basic Plots to Every Story

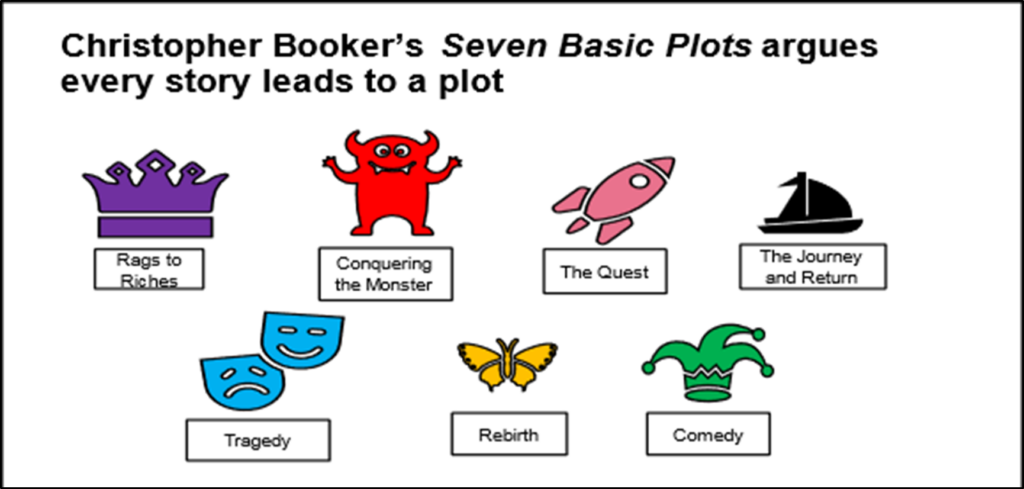

As communicators, we often rely on such devices to better explain ourselves. In fact, we regularly utilize common narratives between sender and receiver. Christopher Booker, an English journalist and author, studied stories from across the globe featured in books, movies, music, plays, and poems. Entitled The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Booker (2004) recounted the common plots within most stories (as shown in Exhibit 1.5). These plots include overcoming the monster, rags to riches, the quest, journey and return, comedy, tragedy, and rebirth. While most of our own stories have purposes of their own, there are certainly elements of each that can be utilized to describe our experiences.

Exhibit 1.5—Christopher Booker’s Seven Basic Plots

|

Plot |

Description |

|

Rags to Riches |

An unrecognized hero overcomes adversity to be lifted out of obscurity. |

|

Conquering the Monster |

The hero overcomes a menacing threat to their environment, others, and self. |

|

The Quest |

Human imagination guides the hero forward on a yet-to-be-experienced adventure. |

|

The Journey and Return |

The hero is transported from their world into others, then home again to reflect on the journey. |

|

Tragedy |

Difficult figures or entities are brought down to their untimely demise by a fundamental flaw they often cannot otherwise correct or see. |

|

Rebirth |

A hero experiences a new life or purpose after difficult and overwhelming setbacks. |

|

Comedy |

An unlikely hero or community rises through challenges and is seen for their accomplishments. |

You may still be struggling with how these narratives fit into your everyday storytelling academically, personally, or professionally. To get your creative juices going, we will provide some examples.

- A rebirth story: Jim talks about the time he overcame the disruptions to his life while learning to manage his alcoholism.

- A tragedy narrative: Suyeon discusses a brilliant yet fundamentally flawed supervisor, who was cruel to his subordinates and in turn was promptly dismissed after costing the company a lot of money.

- Journey and return: Ingrid might discuss her college experience in her valedictory address. While doing so, she tells a story about the graduates’ future; she might borrow from quest narratives.

- Rags to riches narrative: Sports teams that win Cinderella Story championship games or stories like Oprah Winfrey’s rise to fame.

Step-by-Step Instructions to Plot Your Own Basic Story

Step-by-Step Instructions to Plot Your Own Basic Story

Take a story that is important to you, could be meaningful to others, and which you would be willing to share, and construct a story using just one of the plots. Refer back to Freytag’s Pyramid on story structure. Keep in mind a basic story needs a beginning, middle, and end. After constructing the story, find someone and share it with them. How did it go? What was it like to formally use the narrative? What were some benefits or weaknesses to this method?

Ten Great Stories Every Leader Should Tell

Beyond those plots, author Paul Smith (2019) provided insight into common stories that organizational leaders should utilize to connect with audience members. We have found these stories depicted in The 10 Stories Great Leaders Tell, much like the previously discussed plots, to be insightful, interesting, and refreshing for eager audiences in workplace cultures. These stories, described in Table 1.5, range from founding stories to the customer profiling of who we serve stories. These 10 stories match the functions of most organizations to such a degree that at times they seem universal. The work of Smith (2019) responds to the prevailing drive for professionals to engage in more storytelling while making it predictable, recognizable, and most importantly, structured for those doing the work.

Table 1.5: Story and Theme of 10 Stories Great Leaders Tell

|

Story |

Theme |

|

Where we came from |

A founding story |

|

Why we can’t stay here |

A case-for-change story |

|

Where we’re going |

A vision story |

|

How we’re going to get there |

A strategy story |

|

What we believe |

A values story |

|

Who we serve |

A customer story |

|

What we do for our customers |

A sales story |

|

How we’re different from our competitors |

A marketing story |

|

Why I lead the way I do |

A leadership-philosophy story |

|

Why should you want to work here |

A recruiting story |

It’s important to remember that Smith’s stories can be powerful tools to frame your argument. Frames follow the structure of your argument and serve as a connecting theme or narrative to reinforce your ideas.

- For example, if you are developing a new product and pitching it within your organization, you could utilize the who we serve or what we do for our customers frames to discuss the idea. We might create the idea of Julia, an 18–24-year-old female-identifying consumer who has an interest in apparel. Using Julia as our frame, we could describe her demographic, the buying power of that demographic when amassed globally in the billions, and how they are currently underserved for such products.

- A founder of a start-up could utilize a where we came from frame to discuss the history of the organization and returning to some of the fundamentals of customer service that helped create their products. They could also point to some much-needed innovation by using a why we can’t stay here frame or talk about the future through a where are we going story.

1.4 Exercise 1: Identifying a Storytelling Narrative for Use

Learning Objective #4—Listen critically to identify powerful narratives and use effective storytelling to frame meaning messages

Which of these stories resonates most with you? If you found more than one that worked well with your organization or team, consider what venue, space, and timeline you might sketch out to reach more audience members. Be sure to document the results during your exercise and spread the word to others about their ease.

Which of these stories resonates most with you? If you found more than one that worked well with your organization or team, consider what venue, space, and timeline you might sketch out to reach more audience members. Be sure to document the results during your exercise and spread the word to others about their ease.

Think of how such stories can fit into your slides and data visualization. These narrative devices can be employed subtly, directly, or implicitly to reinforce your ideas without distracting the audience. Returning to the core of this chapter, utilizing story, frames, or narratives to encase your evidence fulfills the very notion of Aristotle’s ethos, pathos, and logos.

Chapter 1 Summary

There has been a lot of information to process in this first chapter! You were introduced to multiple topics that provide a foundation for audience-driven communication through data visualization. Special attention was placed on the power of clarity to express ideas and data effectively.

This chapter opens with Aristotle’s credible speaker utilizing ethos, pathos, and logos—the experiences, emotions, and motivations accompanying each speaker in their communication efforts. These factors make communication complex and dynamic. Communication models serve as tools to organize the complexities of the interplay of communication and to predict the connection between speaker and audience. The Transactional Model was highlighted specifically for its recognition of the experience between sender and receiver utilizing demographics and psychographics.

This chapter then turns to the powerful use of persuasion and storytelling to deliver effective messages. Strong communicators use a combination of direct and indirect persuasion models. Barbara Minto’s (2021) Pyramid Principle, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, and SCQA were highlighted for their ability to frame powerful messages.

Our influence, arguments, and ideas are a form of storytelling. Storytelling in communication design is an effective tool for an audience-centered experience. Storytelling frameworks such as Freytag’s Pyramid for organization and Christopher Booker’s Seven Basic Plots for reasoning strengthen the speaker’s intended message. An overview of different types of narratives is provided to spark ideas for designing messages.

Communicators need to analyze the intended audience. This chapter introduced you to the speaker’s responsibilities throughout the design process as well as the presentation of data. The Buffet Effect describes the cognitive overload audiences might feel when looking at overwhelming (messy) data. Awareness of biases and audience perception are necessary for reaching diverse audiences. How a speaker uses their own biases within their message also plays a role.