4 Content and Structure

Chapter Goals

This chapter is designed to help you:

Understand:

- The terms scope and sequence

- What should be included in the scope of a discipleship curriculum

- The importance of flexibility in sequencing

Be able to:

- Develop an appropriate curricular scope for a specific target audience

- Organize curriculum content into relevant themes and topics

Every profession is associated with a specific body of knowledge, what one has to understand, value, or be able to do to hold that position. Airline pilots only have to be seventeen to get a private pilot certificate, but to fly for an airline, they must be high school graduates or have completed a GED, though most airlines prefer a four-year college degree. A pilot has to be proficient in reading, writing, speaking, and understanding English. Pilots must also be in good health and obtain a Federal Aviation Administration medical certificate. They must have strong spatial awareness and coordination. Regarding emotional stability and personality traits, pilots need to possess excellent communication skills, be able to work with a team, demonstrate leadership, be decisive and quick-thinking, and demonstrate self-confidence.[1] Those are the personal qualifications, but that doesn’t include everything a pilot has to learn. That’s a more complicated list.

Pilots have to become familiar with the aircraft and the parts of the plane they’ll fly. This includes external components like the wings and ailerons and also the cockpit instruments, including the navigation and communication systems. The fuel system, oil, and electrical systems also have to be understood, as well as the aircraft engine. A pilot has to be able to compare and contrast the performance of different aircraft using charts and understand how to file accurate flight logs and communicate with maintenance personnel.

Pilots also learn applied physics by studying aircraft maneuvers and investigating the different forces at work, such as Bernoulli’s principle, which explains how various air pressures flowing over and under an airplane wing generate lift. Additionally, pilots need to understand how to keep an aircraft balanced in flight by understanding how the weight of cargo, passengers, and fuel impacts its performance. A pilot’s training includes a study of aeromedicine, focused on how flight affects the human body. A pilot must understand how atmospheric pressure and other aerodynamic forces can impact the passengers and crew. Pilots must be able to react effectively when medical emergencies take place on their aircraft. Besides understanding the aircraft and how it functions and how to care for those within the plane, a commercial pilot also has to have an understanding of weather conditions that impact flying. They must study weather phenomena, such as cloud formations, fronts and air masses, humidity and temperature, wind changes, and weather hazards, including thunderstorms and various types of precipitation.

The list of what a pilot needs to be, understand, and do is already quite long, but there is more. Flying the aircraft requires learning to navigate—plan, control, and record an aircraft’s movement from one destination to another. Pilots must follow the visual flight rules, which include using visual cues, magnetic compass readings, and dead reckoning (the process of determining your position based on the last known position). Using radio navigation, air traffic control radar, and flight computers is also part of the process. Commercial pilots must also be competent in instrument flight rules to fly when they can’t use visual cues. They must learn how to use GPS systems, nondirectional beacons, and VHF omnidirectional range radio transmitters to position their aircraft to stay on course. They must learn what to do in emergencies if all navigation and communications systems fail.

Finally, learning to fly an aircraft requires learning how to prepare, including preplanning a route and doing system checks. Other necessary skills include learning how to taxi, take off, and land with the wind or in a crosswind; how to follow airport traffic patterns when entering or departing; how to fly straight and level and make level turns; how to make climbing turns; and how to avoid collisions, wind shear, and wake turbulence. Additional necessary skills include descending the aircraft, including with turns or high and low drag configurations; flying at different speeds; handling stalled engines and other equipment malfunctions; proceeding in an emergency; and performing forward slips and sideslips. Knowledge of high-altitude operations, postflight procedures, and night flying experience are also essential.[2]

As you read over this extensive list of what it takes to be a pilot, you might have been overwhelmed, or you might have been grateful to realize that the person who flies your commercial airplane has such an extensive amount of tested knowledge and experience! This list represents a significant part of a curriculum, the planned content of the journey toward becoming a commercial pilot. This body of knowledge is referred to as scope. As you can imagine, there is also a structure or order to the way this content is taught and learned. A pilot doesn’t learn how to take off before learning how to taxi, and those lessons don’t take place until a pilot understands the aircraft’s engine and instruments. This structure and order of a curriculum plan is known as sequence.

Focus Activity

- Think of a specific profession or job and identify everything that would be included in the scope of qualifications for that position. Separate your list into attitudes or values one would need to have, information that should be known and understood, and specific motor skills required by someone in this career.

- What might you include in the scope for a disciple? What attitudes, values, information, and skills should a disciple possess and continue to develop?

Scope

A helpful way to understand scope is to think of other uses of the term. A microscope brings into sharp focus whatever has been placed on a slide underneath the scope. A telescope only reveals a portion of the sky that is within the range of where the scope is pointing. The same is true of a rifle scope. There is an entire landscape in front of a hunter, but the target appears within the circumference of the scope used for sighting the prey. With that understanding, we may think of the scope of a curriculum as everything within the range of a curriculum’s mission. It is the entire field of what is appropriate to deal with in a curriculum designed for a particular purpose. This use of the term encompasses everything that could possibly be included, even if it isn’t covered in a plan. While publishers typically use the term scope to refer to what is actually included in their curriculum plans, a more accurate term for this might be the content. Instead of the entire relevant scope, it describes what has been selected for inclusion in the curriculum, even though some possible topics have been omitted.

Why would curriculum designers only select part of the scope to include in their plan? Why not make sure that everything is covered? A scope is often limited because of the intended audience. The faith level of the students might dictate the inclusion of some content areas in a curriculum and the exclusion of others. The mission of making disciples and fostering spiritual formation must always consider the cultural and developmental characteristics of those for whom it is intended. There are topics and truths within Scripture that may not be appropriate to teach to young children, for example. Theologian and teacher L. Harold DeWolf suggests that the manner in which we teach various parts of the scope should differ depending on the age group, though he believes that we should teach the full scope of Christian education to all ages. He states, “The longer I have taught at both senior and adult levels, the more firmly convinced I am that the whole gospel must be taught at each of these levels, almost as if it had never been taught before.”[3] While some argue that everything within Scripture is appropriate for everyone, most curriculum designers focus only on what is most relevant for a particular age group.

Some curriculum developers may omit theological perspectives or spiritual disciplines that differ from a church or ministry’s tradition or doctrinal position. Another scope consideration is time. If a curriculum plan is designed for a ministry that has a start and end date, such as a Vacation Bible School, or for a particular stage of development, such as for teenagers, it would not be possible to adequately teach everything that could possibly be included within the scope. Another practical consideration for selecting content from within a possible scope relates to the background of those teaching. For instance, if a curriculum plan is designed to be led within a context where those leading are newer Christians or aren’t highly educated, it might be advisable to focus on content within the teachers’ areas of expertise.

If a curriculum plan is designed by a church focusing on spiritual maturity and learning across the entire lifespan, then an attempt might be made to include a comprehensive scope. Still, it will be necessary to determine which parts of the scope will be covered within various ministries, in what order, and for which groups within the church. In effect, there will be a curriculum within the curriculum. A lifelong race will be constructed, but it will take place in stages. It is more common to develop a specific curriculum for a particularly selected target audience, often defined by life stages. That is the perspective from which this book is written, though the same principles and procedures would apply on a broader scale.

Selecting which parts of a scope to omit must be done with care, but it is part of the overall process. Those topics chosen for omission are referred to as the null curriculum. They are part of the scope but are nullified in the curriculum because there are no plans to cover them. What has been selected for inclusion is often called explicit curriculum.

One aspect of a scope falls outside of either one of these categories. It isn’t explicit and it isn’t null, but it is hidden. Hidden curriculum refers to content that is not intentionally planned but is often intentional in terms of outcome. It isn’t hidden in the sense that it is a secret set of indoctrination goals kept from the learners. Hidden curriculum refers to what is learned in addition to what is explicitly stated within the scope. It is implicit, or implied. Think of hidden curriculum as the understandings, values, or attitudes students gain from the total curricular journey. Students often graduate from high school and leave behind a youth ministry that they love. The leaders and relationships have shaped their value for the community and had a positive influence on their understanding of the Christian life. Their commitment to that local church may become a standard by which they measure their future involvement in a new church. These outcomes were never explicitly stated, but they were shaped and transmitted throughout the entire teaching and learning experience, their curricular journey. Hidden curriculum may result from the learning context, how the environment is arranged, the group size, the personality of the leader, or the connections made with other learners. Each of these characteristics can shape what a student takes away from an experience.

Hidden curriculum is often implicitly taught through modeling. The expectations for interpersonal interactions, the standards of behavior expected, the style of worship, and the community and global needs we emphasize all shape the hidden curriculum. A ministry’s core values, when lived out, powerfully impact the totality and outcome of the spiritual formation curriculum because the personality of churches and ministries shapes the discipleship journey. The transmission of these values and standards is aspirational, something hoped for, but when they aren’t identified in the scope, they become part of the hidden curriculum.

In describing school-based education, Elliot Eisner emphasizes the reality that explicit curriculum is what is most easily recognizable, but null and hidden (implicit) curriculum also shape learning outcomes:

Schools also teach through the implicit curriculum, that pervasive and ubiquitous set of expectations and rules that defines schooling as a cultural system that itself teaches important lessons. And we can identify the null curriculum—the options students are not afforded, the perspectives they may never know about, much less be able to use, the concepts and skills that are not part of their intellectual repertoire. Surely, in deliberations that constitute the course of living, their absence will have important consequences on the kind of life that students can choose to lead.[4]

Focus Activity

- Reread the quote at the beginning of this chapter. Use your creativity to discover connections between Pooh’s and Piglet’s views of a good day and the concepts of explicit, null, and hidden curriculum.

- How would you describe the hidden curriculum within a ministry or academic setting where you are currently involved? What have you learned in this setting that isn’t part of the explicitly stated curriculum plan?

- As you think about this same ministry or academic setting, can you think of components of the scope that are null? In other words, what could be part of this learning experience that would meet the stated purpose but is not part of what is covered or taught?

Organizing the Scope

It can be overwhelming to think about a curricular scope, let alone determine what will constitute the actual explicit content. For our purposes, we will begin using the term scope interchangeably with content. In other words, throughout the rest of this book, scope will refer to the breadth of what is intentionally included in a curriculum plan. As stated previously, this is the way publishers describe their various curricular materials, only referencing what they choose to cover in their resources. In your planning, you will begin by identifying a scope that is suitable for the curricular mission, and then you will determine the content of your curriculum or actual portions of the scope you will include. We will refer to that as the scope of your curriculum. This use of the term will minimize confusion as you develop your plans.

An important first step in determining scope is to review the intended mission. What is the purpose of the plan, and what is necessary for students to believe and understand for that to be accomplished? What do growing disciples need to know, understand, value, and exhibit? How would you begin listing everything? It is still an enormous focus, but it offers clues on bringing structure to the planning. The process becomes more manageable if you think about organizing the scope into various parts. Are there natural ways to categorize the scope? What guidelines might allow you to think about the scope in smaller, more manageable components?

In the mid-twentieth century, the Cooperative Curriculum Project (CCP) was initiated to provide guidance for the educational ministry of the Church. It was an interdenominational effort, resulting in an extensive plan that could be adapted and used by denominations to help “the church in its task of nurturing persons in the faith, thus preparing them for the mission of the church.”[5] The project described the curricular scope as “the whole field of relationships viewed in light of, or from the perspective of, the gospel—God’s whole continuous redemptive action toward man, known especially in Jesus Christ.”[6] This focus on all relationships in light of the gospel offers a guideline that the CCP used to bring organization to the curriculum. It is part of what is known as an organizing principle. Howard P. Colson and Raymond M. Rigdon explain an organizing principle as “the rationale for the approach curriculum builders take to assure the proper relation of the design elements in a curriculum plan. The organizing principle is also a valuable instrument for testing the curriculum plan to see that it has in it the essential elements of design in proper relationship.”[7]

The CCP’s stated organizing principle was as follows:

The learner “becomes aware of God through his self-disclosure…and responds in faith and love” when through involvement in the Christian community he comes face to face with the great concerns of Christian faith and life as they are relevant to him in his situation by “listening with growing alertness to the gospel and responding in faith and love.”[8]

This statement provides organizational clarity by suggesting that the curriculum plan’s intent is for students to grow in their awareness of God, commit to becoming a disciple, and become part of a local church where the scope will be encountered as it is relevant to their lives and that their participation in the life of the Church will contribute to even greater levels of commitment and growth. The scope will rely on the organizing principle for its development.

Remember that the CCP’s scope included all of the students’ relationships in light of the gospel. As this group further developed the scope of their curriculum plan, they organized their thoughts around the Christian experience of man under God, man’s relationship to man, and the experience of man in the world. These three ideas are rooted in Scripture and are the foundational realities that gave shape to the CCP’s scope. To make the development process more manageable, the CCP organized the scope into five curriculum areas: life and its setting, revelation, sonship, vocation, and the Church. None of the areas is more significant than any other, and they aren’t sequenced in any order. They are simply ways of thinking about the entire scope to assist in planning.

Think of your scope in terms of a home. Families live in homes, and families are the cradle or foundation of existence. They matter, so where they live also matters. It should be a place that provides shelter, protection, comfort, and nurturing and a place where family members can grow into responsible and fulfilled individuals as they interact with those who live with them. Each of the rooms in the dwelling place represents a distinct area designed to contribute to the overall purpose. A house may have bedrooms, a kitchen, bathrooms, a laundry room, an office, a family room, a garage, an attic, or a basement. These rooms represent the various areas of scope, with the house itself representing the entire scope.

Each of the areas in the CCP’s plan has a unique focus or perspective, and each area is further divided into themes or major motifs that are important throughout the lifespan. For example, the area of “life and its setting” is about the meaning and experience of life. The themes assigned to this area are man discovering and accepting himself, man living in relationship with others, man’s relation to the natural order, man’s involvement in social forces, man’s coping with change and the absolute, and man’s creativity with life’s daily routines. The plan explains the meaning of each theme and provides biblical examples, then identifies specific ways in which each theme is significant for various age levels.[9] These age-level considerations are listed and can be considered as appropriate thematic topics to be included in a plan for a particular age-focused curriculum plan.

<

Reflection Exercise

- Can you describe the meaning and importance of an organizing principle for ministry?

- Review the work you have done for your curriculum plan. As you think about your mission, core values, and target audience, how would you describe an appropriate organizing principle for your plan?

Areas, Themes, Topics, and Subtopics

One approach to determining a curricular scope is for a group to brainstorm everything that could or should be included in a ministry for it to realize its overall mission. Once the list is exhausted, the items can be organized into general related areas, with all related subjects grouped together. They can be further organized or grouped by major themes and associated topics. For obvious reasons, this is not the best strategy for developing a comprehensive scope. Entire categories can be overlooked, the scope can be heavily influenced by those who participate in the brainstorming session, and the experiences and faith maturity of the planning group will limit the ideas generated from the brainstorming session.

Starting with a general framework that identifies areas of the scope is advisable. This was the approach of the CCP. This framework should follow the organizing principle you crafted from your plan’s preliminary elements. Think about the mission, vision, core values, target audience, and teaching/learning context and weave the ideas together into a guiding principle to help you organize the plan. Once you have identified the areas, or the big chunks of your scope, then you can begin to identify each of the major themes that should be included for each area. Continue this process by identifying more specific topics that further define each theme. Subtopics add more specificity to the scope, identifying various aspects of each topic that more narrowly define the content.

It may also be helpful to think in terms of units of study appropriate for your target audience, related to various topics or subtopics. However, not everything in the scope will be accomplished through a small group, Bible study, or sermon series. Remember that designing a curriculum is like designing a racecourse, and it includes everything students will experience as they run the race. Special events, retreats, camps, and projects related to various components of the scope can all be designed to help students learn and grow. Your plan identifies the boundaries of the curricular racecourse through its various areas, themes, topics, and subtopics. The race itself will involve formal and informal teaching and learning sessions as well as events and experiences related to the scope.

When designing a curriculum for the first time, it may be confusing to think about areas, themes, topics, and subtopics in the abstract. Most of your previous educational experiences utilize these principles, however. The following excerpts from a university’s core curriculum plan are intended to clarify further how these concepts are related and how they can be implemented. Students enrolled in this university select a variety of majors, so their comprehensive curriculum isn’t identical. However, as is the case with many universities, there is a core curriculum plan designed to help students accomplish the school’s mission, regardless of which major they declare.

University Core Curriculum

University Mission: With the conviction that all truth is God’s truth, the University exists to carry out the mission of Christ in higher education. Through a curriculum of demonstrated academic excellence, students are educated in the liberal arts and their chosen disciplines, always seeking to examine the relationship between the disciplines and God’s revelation in Jesus Christ.

Organizing Principle for the Core Curriculum: The…University Core Curriculum challenges students to integrate knowledge, values, and skills into a coherent worldview that equips them for a life of faithfulness to God through service in the world.

Scope Areas for the Core: Faith Integration, Critical Thinking, Communication, Multicultural Thinking, Empirical Thinking, Creative Expression

-

-

- Themes Related to the Faith Integration Core Area: Biblical Studies, Christian Faith, Religious Perspectives

- Topics Related to the Biblical Studies Theme: Apocalyptic Literature, The Gospels, New Testament Historical and Prophetic Literature, Hebrew Historical Literature

- Topics Related to the Religious Perspectives Theme: Religions of the World, History of Christianity, Religion of Scientific Thought, Philosophy of Religion, Contemporary Christian Theology, God and Ethics, Philosophical Theology, Theological Bioethics

- Themes Related to the Empirical Thinking Core Area: Mathematical Science, Natural Science, Social Science, Wellness

- Topics Related to the Social Science Theme: Principles of Macroeconomics, Public Policy, Introduction to Psychology, Principles of Sociology, Cultural Anthropology

- Themes Related to the Faith Integration Core Area: Biblical Studies, Christian Faith, Religious Perspectives

-

As you can imagine, each topic represents a semester-long course of study, and each course has its own set of subtopics and objectives.[10] This model can be used to construct a scope. Determine your mission and your organizing principle and establish relevant areas that will make up your scope. Then determine themes and topics for each area. For each of the topics, begin to think about subtopics related to each one. This is similar to how each course listed in the university example includes its own content. If you have taken a psychology course, for example, you realize that this is a very broad subject and includes many separate units of study on various subtopics in psychology. Identifying your scope subtopics represents a similar approach.

Reflection Exercise

- Look over the various themes the CCP included in the area of life and its setting. Select a couple of the themes and identify three or four relevant topics related to each of the themes you selected.

- Next, select two of the topics you listed for each of the two themes. Create two appropriate subtopics for each topic you selected.

Sequence

When constructing an organized curriculum plan that will guide the ministry’s teaching and learning, it is important to establish a planned sequence for engaging with the various components you selected as part of the explicit curriculum. Consider the order in which it makes the most sense to offer the various themes, topics, and subtopics in the scope to help learners develop. Some topics or subtopics build on one another and require a level of prior understanding before they can be effectively understood.

In chapter 3, you read about Robert J. Havighurst’s view on teachable moments. He proposed that various portions of the scope need to be repeated because age isn’t the only thing that determines learning readiness. Some learners might not be at a point where they can fully understand or appropriate various topics when they’re first presented, so weaving them into the sequence at more than one point will maximize the possibility that everyone will learn what you have determined is important for their spiritual growth. Not everyone will be present for every teaching and learning opportunity. If a student is absent, they will miss out on essential portions of the scope if those are not repeated in various places throughout the curriculum.

The Bible references the importance of sequence and the need for repetition in teaching as part of spiritual growth. Paul describes a group of gullible people that are easily swayed by false teachers because they “are so loaded down with sins and are swayed by all kinds of evil desires, always learning but never able to come to a knowledge of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:6–7, NIV). Another example of why repetition is important is found in Hebrews 5. The author is addressing Jewish Christians who are not at the level of spiritual maturity they should have already attained:

We have a lot to explain about this. But since you have become too lazy to pay attention, explaining it to you is hard. By now you should be teachers. Instead, you still need someone to teach you the elementary truths of God’s word. You need milk, not solid food. All those who live on milk lack the experience to talk about what is right. They are still babies. However, solid food is for mature people, whose minds are trained by practice to know the difference between good and evil.

Hebrews 5:11–14, GW

The key to developing an appropriate curricular sequence is to consider how best to arrange the elements of the scope for spiritual growth. If the plan is developed for an entire ministry, then sequencing might also require determining which themes or topics to include for various age groups. If a curriculum is developed for one particular age group, then there is a limited time frame to consider when planning a sequence. For example, if it is a curriculum plan for high school students, it will probably be a three- or four-year sequence, depending on which grade levels are considered high school.

When developing a scope, publishers tend to think of cycles of learning, with entire cycles repeated every three or four years, sometimes less frequently and sometimes more often. If a ministry develops a separate curriculum for intergenerational learning or for specific purposes, such as a new believers’ program, the length of the sequence and cycle needs to be considered in the planning stages for both the scope and the sequence.

Excerpts from a Published Scope and Sequence

Three-Year Plan for Children[11]

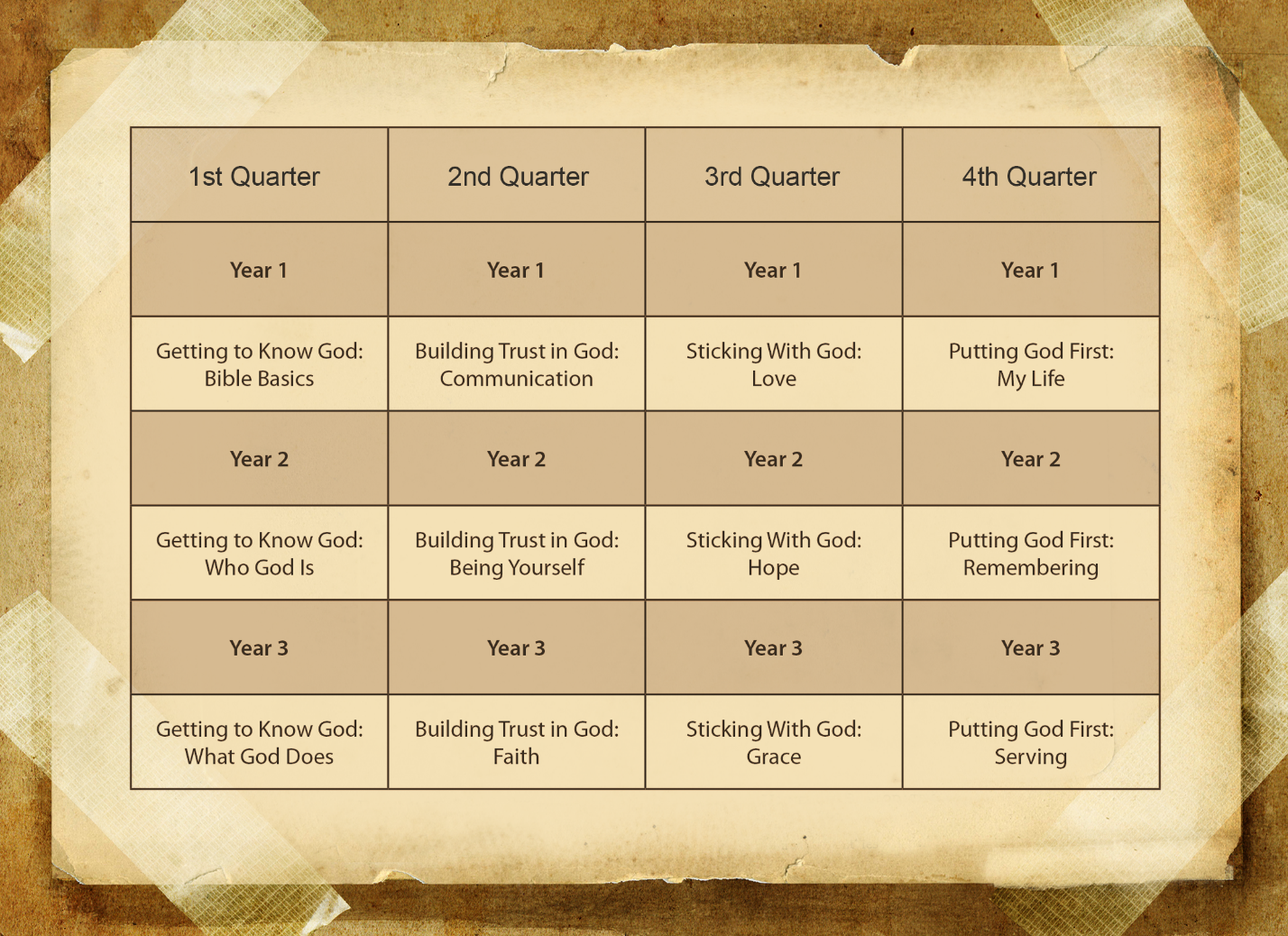

Areas: Getting to Know God, Building Trust in God, Sticking With God, and Putting God First

Themes Related to Area 1 Getting to Know God

Themes: Bible Basics, Who God Is, What God Does

Topics Related to the Theme: What God Does

*God helps us, God guides us, God keeps His promises, God protects us, God forgives us, God provides everything we need, God always stays with us (is faithful), God heals, God does miraculous things, God uses common people to accomplish his plans, God looks for the lost, God longs for us, There are some things God will not do

Themes Related to Area 2 Building Trust in God

Themes: Communication, Being Yourself, Faith

Topics Related to the Theme: Faith

*Faith is believing what you can’t see, Have childlike faith in God, Have faith that God has plans for you, Have faith that God knows best, Have faith when you’re in trouble, Have faith when things look tough, Have faith when you don’t know everything, Have faith when you need help, Have faith when others need help, Have faith when you don’t have much, Have faith when you don’t see the answer, Have faith when you stand up for God Have faith in Jesus’s power

Themes Related to Area 3 Sticking With God

Themes: Love, Hope, Grace

Topics Related to the Theme: Grace

*God’s grace is a free gift, Share God’s grace with others, We can ask for God’s grace, God’s grace cleans us, We need God’s grace, God showed His Grace by sending His Son, God’s grace rescues us, God’s grace makes our sins disappear, God’s grace changes us, God’s grace helps us have good relationships, Anyone can ask for God’s grace, God’s grace gives us confidence, We give grace because we have received It from God

Themes Related to Area 4 Putting God First

Themes: My Life, Remembering, Serving

Topics Related to the Theme: Serving

*Jesus taught us to share what you have, God wants us to always help others, God can help us be kind to everyone, God wants us to make peace, Jesus tells us to share our faith, Jesus wants us to help others, Jesus wants us to serve willingly, God says don’t give up, God wants us to be hospitable, God can help us help the poor, God wants us to be a friend, Jesus tells us to be generous, Jesus wants us to put others first

The following illustration shows how the publisher has sequenced the areas and themes over a three-year cycle. Notice that they aren’t taught in a linear progression. Every year in the curricular sequence includes all four areas of the scope, but different themes are covered each year. This graphic doesn’t include the specific topics covered week to week, but this information would be available in a more detailed scope and sequence plan. While none of the exact themes and topics are repeated within the three-year cycle, important biblical truths are covered multiple times in various ways.

Focus Activity

- Read over the abbreviated list of themes and topics in the previous sample. Which of the topics do you think will help students understand the gospel message of salvation? What does this tell you about the importance of both scope and sequence in accomplishing a curricular mission?

- What additional themes or topics might you include for each of the curriculum areas if the plan was designed for adult learners?

Significant Concepts

areas, themes, topics, and subtopics

explicit, hidden, and null curriculum

organizing principle

scope

sequence

Putting It All Together: Chapter Assignment

Continue developing your curriculum plan by identifying an appropriate scope for your intended audience. Refine the organizing principle you created, then use it to specify four areas for your scope. (Your actual final plan may include more than four.) Remember that your organizing principle should reflect your overall mission, vision, values, and target audience. Once you have identified your four areas, list a minimum of four associated themes for each. Next, write a minimum of three related topics for each theme. This will be a total of four areas, sixteen total themes, and forty-eight specific topics. Finally, for each topic, list two related subtopics. This will be a total of ninety-six subtopics. While this may seem like a lot, keep in mind that an overall comprehensive curriculum plan would probably contain many more themes, topics, and subtopics.

- “Requirements and Qualifications to Become a Pilot,” L3 Harris Flight Academy, February 2024, https://l3harrisairlineacademy.com/en-us/how-to-become-a-pilot-in-the-usa/qualifications-to-become-a-pilot-usa/. ↵

- “What Will I Learn in Flight School?,” Spartan College of Aeronautics and Technology, February 2024, https://www.spartan.edu/news/what-will-i-learn-in-flight-school/. ↵

- DeWolf quoted in Howard P. Colson and Raymond M. Rigdon, Understanding Your Church’s Curriculum, rev. ed. (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1981), 60. ↵

- Elliot Eisner, The Educational Imagination (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2002), 97. ↵

- Cooperative Curriculum Project (CCP), The Church’s Educational Ministry: A Curriculum Plan (St. Louis: Bethany Press, 1965), 3. ↵

- CCP, Church’s Educational Ministry, 13. ↵

- Colson and Rigdon, Understanding Your Church’s Curriculum, 50. ↵

- CCP, Church’s Educational Ministry, 36. ↵

- The CCP’s complete plan is outlined in The Church’s Educational Ministry: A Curriculum Plan. This 848-page book describes each aspect of the plan in detail. Each area is thoroughly explained, and learning tasks are also identified for each age level. It is a comprehensive plan that may be useful for those creating their own curriculum. ↵

- This information is a portion of the core curriculum plan for Huntington University, which is included in the Huntington University Traditional Undergraduate Academic Catalog, 2023–2024, vol. 108 (2023): 101–3. ↵

- This is part of Group’s Hands-On Bible Max curriculum scope and sequence for 2008–9. This curriculum has changed over the years and now has a two-year sequence. All of Group’s scope and sequence charts can be downloaded from their website, https://www.group.com. ↵