7 Bringing Curriculum to Life

Chapter Goals

This chapter is designed to help you:

Understand:

- Key learning styles and preferences

- Categories of learning methods

- How to create curriculum resources

Be able to:

- Design learning activities for various learning styles

- Create learning activities that adhere to principles of learning

- Construct lesson plans and units of study

How do you help someone change their perspective when their reasoning seems illogical? How can you dispel misinformation or shatter stereotypes that have become deeply embedded and impact both beliefs and attitudes? It is a challenge to transform the opinions of others and foster change.

Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, has most often been portrayed in movies as an evil and manipulative woman. Her beauty and selfishness are highlighted, with little to no references to her intellect or positive qualities. Cleopatra was actually Greek, though she did speak Egyptian, one of about ten languages at her command.[1] Julius Caesar fell in love with her on a visit to Egypt, and she returned with him to Rome. The Romans weren’t sure what to think about Cleopatra. They hated the idea of an Egyptian queen in Rome, but they were also mesmerized by her charm. However, when Caesar was assassinated, Cleopatra returned home to Egypt and joined Marc Antony as a naval commander, leading ships against the Roman Empire along with Caesar’s nephew, Augustus. The Romans feared that Cleopatra wanted to rule Rome. When the relationship between Antony and Augustus eventually deteriorated, Augustus made it known that Marc Antony planned to leave lands and bestow titles on the children he had with Cleopatra. This convinced the Romans that both Antony and Cleopatra were their rivals and should be eliminated. The Roman Senate removed all of Antony’s power and declared war on Cleopatra.[2] This negative history between the Romans and the Egyptians probably accounts for much of the way Cleopatra has been portrayed. Eventually viewed as an enemy to Rome, the Romans painted her as a beautiful but seductive, power-hungry temptress. Arabic history remembers her as a powerful, intelligent, strong ruler and a great leader.

Ludwig van Beethoven is considered one of the greatest composers of all time. He was introduced to music when he was quite young, and his first teacher was his very strict father. If he failed to practice correctly, his father would beat him and his mother if she tried to intervene. His resolution to become a great pianist is said to have been motivated by his desire to prevent his mother from being abused by his father. She died young, and his father became an alcoholic. Beethoven relied on private donations for his work, and even though his music was loved by many, he often struggled to raise enough support to continue his creative work.

Though he was considered a great musician, Beethoven’s habits were unconventional. He was considered clumsy, ugly, and untidy, and regardless of many attempts to make him behave, the efforts didn’t seem to work. He once told the archduke that it was impossible for him to follow the rules of social behavior. Beethoven’s music was also unconventional in his use of style and form, which caused him to be alienated from more classical teachers of the time.

He began to lose his hearing in his early twenties, but he continued to compose masterpieces. He eventually became totally deaf, but his ability to inwardly hear the music allowed him to create beautiful music. However, his deafness made it difficult to perform with orchestras because he was unable to keep time with the other musicians. This caused him to be ridiculed by the public. Yet his most widely admired compositions, including the Ninth Symphony, were composed during the last fifteen years of his life.[3]

Vincent Van Gogh was a Dutch postimpressionist painter whose most famous works include Sunflowers, The Starry Night, and Café Terrace at Night. While he eventually became known as one of the most celebrated artists of the twentieth century and a pioneer in the development of modern art, Van Gogh’s artistic abilities were largely ignored during his lifetime.

When he was young, Van Gogh worked in his uncle’s art dealership, but after becoming frustrated and unhappy, he became a Protestant minister. He preached in poor agricultural districts and empathized with those who lived in poverty. Van Gogh began to share in their difficult living conditions, but despite trying to live according to the gospel, the Church authorities decided that he was undermining the “dignity of the priesthood,” and they removed him from his post. That is when he became an artist.

Van Gogh was not considered a great artist during his lifetime and only sold one painting. He was demoted from one art academy because of his inability to draw. However, he continued to work hard and improve his technique. His early failures as an artist haunted him throughout his life, and he was troubled by a sense of inadequacy. Van Gogh was also known to have a volatile temper and was considered unstable. He was eventually committed to a mental health facility, where he lived off and on until his death.

Van Gogh didn’t hold a regular job but put his whole being into his art, often neglecting his health, appearance, and finances. His brother Theo often sent him money and provided him with painting materials. While aware of how he was perceived, Van Gogh remained passionate about his vision for life, as evident in this letter to his brother:

What am I in the eyes of most people—a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person—somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then—even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart. That is my ambition, based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion.

—Vincent Van Gogh (Letter to Theo, July 1882)[4]

What do these historical snapshots reveal about human nature? They remind us that people are more complex than we can observe from the outside, that others’ opinions aren’t always accurate, and that not everyone values the same things or views life in the same way. Stereotypes and prejudice can prevent us from changing our beliefs or opinions.

Discipleship isn’t about indoctrination or persuading people to agree with us, but it is about helping others acknowledge biblical truth about God as revealed in Scripture. Sometimes, this involves clearing up misconceptions, and other times, it is about introducing people to ideas that are brand new. Regardless of where people are in their current understanding, the invitation to discipleship is open to everyone. This is the work of spiritual transformation and the purpose of a curriculum plan. This will require teaching and learning resources that take into account all aspects of human diversity and provide all persons the opportunity to grow into Christlikeness, no matter where their journey begins.

Focus Activity

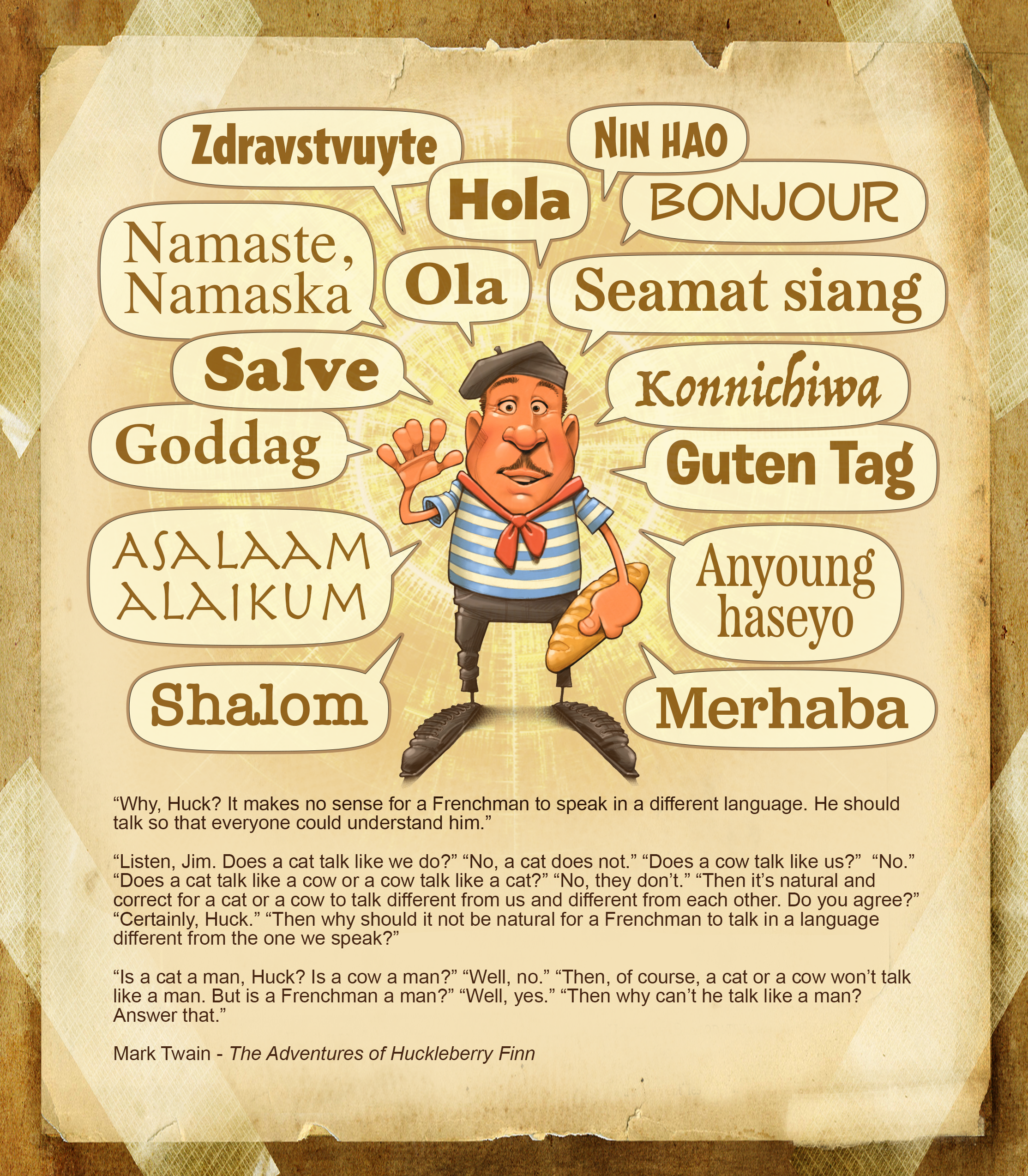

- Review the opening quote from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. What types of challenges might you encounter in teaching someone like Jim?

- What are some specific areas of needed change or learning challenges represented by the lives of Cleopatra, Beethoven, and Van Gogh? Think in terms of individual needs to consider in teaching and learning, such as cognitive abilities, cultural diversity, physical disabilities, or mental health concerns.

- What lessons about curriculum design and spiritual formation can be learned from these examples?

- Can you think of people within your own life context who exhibit similar discipleship challenges?

- What biblical principles might be helpful to remember when trying to disciple learners from diverse backgrounds?

Learner Considerations

A curriculum plan is a complex document, full of potential but completely useless unless it is implemented. In the introduction to this book, it was noted that it is important to design teaching and learning experiences that lead toward spiritual transformation for a specific target audience. Unplanned experiences are also part of the curricular journey because we recognize that not everyone learns the same things or in the same ways, even when participating in the same curriculum. All persons bear God’s image, but that doesn’t mean people act, think, or respond the same way. While it isn’t feasible to try to create unique learning experiences for each individual learner, it is important to recognize the variety of ways in which people learn so that the curriculum comes to life for everyone on the journey.

While the focus of this book is on curriculum development and not teaching, there are some commonly understood patterns of teaching and learning that should guide those who select and create teaching and learning experiences for discipleship. Students differ in how they perceive and process information, how they relate to other learners, what motivates them, their level of self-awareness, and how they communicate. These characteristics represent particular learning styles or preferences. When implementing a curriculum plan, it is important to focus on student learning. This necessitates the incorporation of methods and structures that will provide opportunities for students to encounter experiences that intersect with their preferred learning styles. It is important to realize that these are learning preferences and not required conditions for learning to transpire.

Sometimes learning preferences are the result of conditioning. Cultural expectations on the role of the teacher and learner can shape these preferences and even override natural preferences. If students have grown up sitting passively while the teacher lectures, they may be uncomfortable in a situation that expects them to interact or respond to questions. They may hesitate to ask their own questions or participate in a group activity. However, remember that people can learn in a variety of ways, even when the way in which they are taught doesn’t align with their preferences. Change is always uncomfortable, but if our desire is for students to experience life transformation, then we will consider their learning styles and best practices for teaching and learning in our curriculum design. This doesn’t mean that each learning session will incorporate a smorgasbord of learning methods, but it does suggest that variety will be the hallmark of our teaching.

Global or Analytic Learners

Most people interpret the world from one of two main polarities, referred to as either global or analytic. While all learners engage both polarities to some extent, and there are some who make equal use of both, it is more common for individuals to show a preference as either a global or an analytic learner. A study of the behaviors of naval fighter pilots in World War II revealed this understanding. A psychologist, Herman Witkin, began conducting tests to understand why some pilots were able to fly out of a fogbank, retaining their upright orientation, while others emerged from the fog upside down. What he discovered was that some pilots depended more on their field of vision to maintain an upright position and became disoriented by being unable to see their surroundings. He labeled them field-dependent, or global, learners. Others were labeled field-independent learners because they were able to maintain their upright orientation even though they couldn’t see where they were. They fall into the category of analytic learners.[5] Witkin’s research led to our understanding of how learners interact with the world from either a global or analytic perspective.

Which of the following examples best describes you?

1.A friend asks you about a movie you just saw.

A.You tell your friend who was in the movie, you talk through the plotline, and maybe you even quote a few lines of the dialogue.

B.You tell your friend how the movie made you feel and give a general idea of the theme, but you can’t remember who the actors were, even though you do remember what they looked like.

2.Someone asks you how to get to the nearest fast-food restaurant.

A.You explain which direction to head, where to turn, names of streets, and an approximate distance.

B.You confess that you aren’t really sure which streets to take, but you are able to provide a general idea of where to head and you can describe the buildings and scenery they will pass on the way.

If you see yourself as more of an A, then you are probably more analytic, or field independent. If B sounds more like your style, then you might be more global, or field dependent.[6]

Characteristics of a Global Learner

- Recognizes and remembers faces

- Produces humorous thoughts

- Focuses on big ideas

- Interprets body language

- Subjective

- Likes working with groups

- Prefers instructions by demonstration

- Makes emotional appeals

- Prefers fantasy, poetry, or myth

- Processes information randomly

- Remembers pictures or images

- Paraphrases

- Likes open-ended assignments

Characteristics of an Analytic Learner

- Recognizes and remembers names

- Focuses on the meaning of words

- Produces logical thoughts

- Emphasizes details

- Objective

- Likes working alone

- Prefers verbal instructions

- Makes emotional appeals

- Prefers realistic stories

- Processes information sequentially

- Reads for details or facts

- Outlines

- Likes well-structured assignments

Reflection Exercise

- Refer to the lists of principles of learning from chapter 5 for understanding and for attitudes, values, and beliefs. Which principles would be most helpful for global learners? For analytic learners?

- Select three of the goals and indicators you created in chapter 6. Describe learning activities for both global and analytic learners that would help students achieve each of these goals and indicators. Use the principles of learning to help you create your learning activities.

Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Learners

Learning occurs as we take information in through our senses, including hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, or touching. The three main ways information is perceived are auditory, kinesthetic, and visual. Most traditional teaching, especially for spiritual transformation, relies on auditory methods, though successful learning for the majority of learners often depends on all three modalities.

Auditory learners benefit from hearing, listening, and speaking. Speaking is especially important for the auditory learner, which emphasizes the importance of discussion. Visual learners like to see what they’re learning from charts, diagrams, graphs, or pictures. For instance, they are more apt to remember and learn biblical content if they read it themselves as opposed to listening to someone else. Taking notes is also beneficial. Kinesthetic learners need to become physically involved as they learn, so sitting still can be distracting. Doing a project is beneficial, but so is pacing or walking around. Kinesthetic learners are more likely to remember what they have done than what they have discussed, heard, or read.

Reflection Exercise

- Select three of the goals and indicators you created in chapter 6. You may use the same ones you used for the previous Reflection Exercise. Describe learning activities for auditory, kinesthetic, and visual learners that would help them achieve each of these goals and indicators.

- How might you structure a discipleship small group to benefit all three types of learners, auditory, kinesthetic, and visual?

Learning Style Inventory

Curriculum includes more than the learning content; it also consists of everything a learner experiences. The room arrangement, the time of day, the fellow students, and the temperature all impact learning. Kenneth and Rita Dunn developed the Learning Style Inventory (LSI) to assess these curricular components by studying student environmental learning preferences. Their research has become one of the most widely used, valid, and reliable assessments of its kind.[7] The LSI identifies a learning style as “a biologically and developmentally imposed set of characteristics that make the same teaching method wonderful for some and terrible for others.”[8] The instrument takes the following learning preferences into account:

- Environmental factors: sound, light, temperature, seating arrangements

- Emotional factors: motivation, conformity/responsibility, task persistence, learning/classroom structure

- Physiological factors: perceptual (auditory, visual, tactile/kinesthetic), intake needs of food/drink, time of day, mobility

- Psychological factors: analytic-global, impulsive-reflective

- Sociological factors: working alone, in a pair, with peers, in a group; relationship with authority; need for variety[9]

As you plan for teaching and learning situations, remember that learners have preferences that impact their learning. The emphasis is on preferences that have an impact, not absolutes. Remember that these preferences aren’t necessary for learning to take place. They may make it easier. Accounting for learning preferences may seem insignificant, but if we want to maximize the opportunity for significant life change, then we need to seriously consider the LSI research as we select where learning will take place, what expectations we place on the students, and how we plan the content.

Focus Activity

- Based on your discipleship learning experiences, which of the LSI characteristics have been most overlooked?

- Which of the LSI characteristics would be easiest to accommodate, and which do you think might be more difficult to include as you design discipleship experiences?

Teaching Methods

Spiritual transformation involves learning, but not all learning is done in the context of a small group or structured learning situation. As you review the goals and indicators you created for your scope, you may decide that a retreat, service project, mentoring relationship, or special event might be the optimum method to accomplish your learning intent. Regardless of the structures you implement, it is important to consider a variety of methods you can incorporate into your plan. Repeatedly using the same methods can suppress learning. Routines can be comfortable, but introducing the unexpected can result in positive tension that leads to learning. Using too many methods can also create chaos that can detract from learning, so it is imperative to consider the audience, the goal, and the available resources when you plan creative ways of teaching that are most likely to lead to life transformation.

There are a number of resources available that describe innovative methods of teaching. The following paragraphs describe the most common categories of methods you may want to consider.

Art Techniques

Using art methods is a great way to engage all types of learners, not just those gifted in art. Using cartoons can allow images to offer commentary on human characteristics and situations more effectively than words. Displaying objects around the teaching environment that represent key ideas or concepts can often communicate or illustrate difficult or significant concepts. Posting a series of drawings, paintings, or pictures can be effectively used in a number of ways. Students can select an image representing an idea or feeling, allowing them to reflect on significant ideas and appropriate meaning. Illustrating events, concepts, or reactions to a passage can be accomplished with any number of materials. Remember, when asking students to produce something, the focus is not on the final product but on the process it takes to create. Maps or charts can clarify facts that are hard to visualize, and montages or collages can offer a variety of images and symbols that highlight a particular theme. Sometimes a picture study can allow students to analyze an artist’s understanding of a concept. Warner Sallman’s Christ at Heart’s Door is an excellent example of how this art method can be used.

Drama Techniques

Drama is often used in teaching children or youth, as in acting out Bible stories or creating role-plays. The method can be effective with adults as well and for higher levels of learning than simple comprehension. Creating hypothetical dialogues or monologues or presenting a short dramatic situation relevant to the topic can generate discussion. Engaging in a simulation to reproduce a situation so students can get a feel for the setting and identify what others have experienced can be impactful.

Learning Games

Games are contests in which players operate according to specific rules in order to achieve a goal. The four key characteristics are contest, players, rules, and goals. Learning games include all four of these characteristics and are marked by a serious learning intent. They can include problem-solving, negotiating, questioning, role-playing, information retrieving, or team building.

Music

Music is often used as an introduction to a learning session to focus the attention of a group of learners. It might also serve to unify a group. However, music is also a powerful teaching method when it is purposefully woven into a plan. It can create an atmosphere to enrich learning and provide a means of worship but also contribute to biblical insights and heart transformation. Instead of music being ancillary, learners can engage in encountering musical content. They might study the lyrics from contemporary songs or traditional hymns to evaluate their message or compare it with biblical teaching. Students could also be encouraged to create new lyrics to familiar tunes that reflect personal or life applications aligned with a session goal.

Pencil-and-Paper Techniques

Note-taking, filling out worksheets, and journaling are probably the extent of the writing methods most teachers incorporate into their discipleship sessions. There are so many more ways to utilize this method, which involves students in clarifying their thoughts and feelings and expressing their understanding. Writing requires learners to engage in deeper thinking than asking for spontaneous discussion. Asking students to create an acrostic built around a significant keyword, writing a review or paraphrase of a Scripture passage, or engaging in a creative writing activity are all positive uses of writing methods. Younger children can benefit from coded messages, crossword puzzles, or puzzles to help them review and process content. Creating hypothetical dialogues, expressing feelings or encouragement through letter writing, completing open-ended stories, or answering open-ended statements are additional ways to incorporate paper-and-pencil methods. Writing poetry, lyrics, haikus, or cinquains requires both creativity and critical thinking. Asking for unsigned responses can provide teachers with an indication of whether their affective goals have been achieved.

Verbal Techniques

Brainstorming is an often-overlooked method of problem-solving that allows learners to offer spontaneous ideas or solutions without criticism. Large groups can be divided into small groups to discuss problems or case studies before reporting back to the larger group. One discussion method, the circular response, allows everyone to take turns responding to a posed question or statement. No one can speak twice until everyone has had an opportunity, which can alleviate the common problem of having students who dominate a discussion or those who rarely speak. Panel discussions and informal debates can prompt alternate opinions and encourage critical thinking about significant concepts. Interviews, panel discussions, and lectures are other possible verbal techniques to consider when planning discipleship sessions. Jesus’s preferred teaching method was verbal and often involved storytelling:

He did not tell them anything without using stories. But when he was alone with his disciples, he explained everything to them.

Mark 4:34, CEV

Reflection Exercise

- Jesus used a variety of teaching methods designed to help his followers grow in their understanding and commitment. Which methods are represented by the following passages of Scripture? Matthew 5:1–2, Mark 12:13–17, Matthew 18:1–5, Matthew 16:13–20, Luke 10:1–11, and John 8:1–8. What other examples would you include in this list?

- Select one cognitive goal and one affective goal you created in chapter 6. For each goal, create three separate learning activities using three different methodologies. Don’t describe an activity or method you regularly experience. Instead, use your creativity to develop an activity that would help learners engage in deeper spiritual growth. In your descriptions, include all of the necessary details for leading the activity.

- In your experience, what methods are most overused in discipleship settings? Why do you think that is the case?

Crafting Resources

A curriculum plan comes to life when appropriate resources are selected and experiences are planned that bring about spiritual transformation in the life of the learners. These decisions must be made carefully so that the planned goals and indicators can be achieved. Many outstanding curricular resources are available through Christian publishers that may fulfill various purposes of a plan. Events and unique learning experiences can also be designed to help learners accomplish some of the curricular goals. However, sometimes it is desirable to create your own curriculum materials. It wouldn’t be practical or even advisable to attempt to create all of the learning resources needed to successfully implement a curriculum plan. It is tedious work to produce quality materials, and it wouldn’t be the best stewardship of your time. It may be preferable or even necessary at times if your target audience represents a specialized population for which quality resources don’t exist, aren’t readily available, or are cost prohibitive.

There are many approaches to writing curriculum materials or lesson plans. The first step is to understand the purpose of the resources you are designing. Consideration must also be given to the learning context, the experience and expertise of the teachers, and how the resources will fit into the overall scope and sequence of the plan. Lesson plans may be created for an entire unit of study related to a particular topic or subtopics. Units often include four or five weeks of materials, corresponding to a calendar month. According to Lois LeBar, since most discipleship meetings last only about an hour each week, it can be difficult for students to make connections between various sessions unless they are combined into units of study. A unit allows for a more intentional focus, resulting in greater learning continuity for the students. Each session would include one subtopic or piece of the overall subject. An example of a unit on the Holy Spirit might include sessions such as The Holy Spirit as Teacher and Guide, The Holy Spirit as Counselor, The Holy Spirit as Illuminator, The Holy Spirit as Enabler, and The Holy Spirit as Convicter.[10] Of course, units of study can be combined to form a more robust resource to be used over a longer period of time.

Planning for Discussion Groups

If resources are designed for discussion-based small groups, it is important to consider strategies for both disciple-making and community building as you plan. The purpose should always be spiritual growth, but this is maximized when learners feel connected to one another and experience the freedom to interact honestly and without judgment. It will also be important to carefully craft questions that lead learners toward spiritual transformation. Rarely do worthwhile questions simply emerge in the moment. They should be planned and incorporated into the teaching resource. It takes time to write significant questions, but if discussion is the key structure of a small group, the process can’t be overlooked. Obviously, discussions flow out of questions and responses, and a qualified leader will be able to keep the dialogue moving so it doesn’t come across as an inquisition.

Questions

Yes or no questions aren’t helpful, but open-ended questions can help learners make sense of information and think beyond the obvious. Avoid compound questions, those that combine more than one focus. Long-winded questions and those that are obvious, misleading, or irrelevant should also be avoided. Closed questions are those that solicit one particular correct response. These should be used sparingly, as they focus more on factual information and lower levels of understanding. Steer away from them altogether if they rely on one specific Bible translation for a correct response. Challenging questions allow students to think more deeply about the application of the content to their lives. Utilizing each type of question can be helpful. It is also possible to structure questions that lead learners through Bloom’s taxonomy from basic knowledge through evaluation: What did the people do when they heard the news? What did Jesus mean by his statement? When have you observed a similar reaction? How might their disagreement be resolved in an orderly fashion? How would you structure a worship experience in this environment? How well did the Israelites adhere to God’s commands?

Michael Novelli has written a number of resources about Bible storying as a teaching strategy. He recommends using questions from various categories to help learners understand and apply the meaning of the text. Wondering questions require students to consider the story’s content before they begin appropriating meaning. These may include such questions as, Did you notice anything in the story that you hadn’t realized before, what surprised you in the story, or what questions does the story raise in your mind? Remembering questions call for learners to recount specifics of the story, but they should be used sparingly, since they are a form of closed questioning. Interpreting questions take students beyond knowledge to the comprehension level of understanding. For example, How would you describe (key character’s) commitment, or personality, or emotions, or motive? Why do you think X acted the way he did when X? What does this story teach us about God? Why do you think this story was included in the Bible? Connecting questions require application of the biblical content to the life of the learner. Examples of this type of question include, How is this story your story? Where do you see yourself in this story, or how does this story challenge or encourage you?[11]

Planning for Structured Lessons

Spiritual transformation is the work of the Holy Spirit within an individual, but God works with the human teacher to help facilitate that change. LeBar suggests that the teacher “prepare as if it all depends on God; work as if it all depended on you.”[12] God has chosen to work with and through willing Christians to disciple others. He has commanded us to make disciples, and doing so effectively requires planning. In speaking about worship, Paul reminds us in 1 Corinthians 14:33 that “God is not a God of disorder.” When teachers fail to plan, disorder is likely to follow. What is intended as a Bible study can easily devolve into a social gathering that results in very little learning. God expects our best effort at everything we attempt, and discipling others is one of the most significant tasks we can undertake. If we make the effort to plan a curriculum that will lead to spiritual growth in the life of learners, we can’t simply go with the flow when it comes to teaching and hope that our goals will be accomplished:

Let the message of Christ dwell among you richly as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom through psalms, hymns, and songs from the Spirit, singing to God with gratitude in your hearts. And whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.

Colossians 3:16–17, NIV

HBLT

Larry Richards introduced the hook, book, look, took (HBLT) method for creating structured lesson plans. It is a useful approach to lesson planning that can be adapted for any learning environment or target audience.

In their book Creative Bible Teaching, Richards and Gary Bredfeldt suggest that Paul used this approach when he addressed the philosophers on Mars Hill in Athens. When he was walking through the city, waiting for Silas and Timothy, Paul noticed all of the idols and one in particular that was dedicated to an unknown god:

Paul then stood up in the meeting of the Areopagus and said: “People of Athens! I see that in every way you are very religious. For as I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: to an unknown god. So you are ignorant of the very thing you worship—and this is what I am going to proclaim to you.

“The God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands. And he is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything. Rather, he himself gives everyone life and breath and everything else. From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands. God did this so that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us. ‘For in him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring.’

“Therefore since we are God’s offspring, we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent. For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead.”

When they heard about the resurrection of the dead, some of them sneered, but others said, “We want to hear you again on this subject.” At that, Paul left the Council. Some of the people became followers of Paul and believed. Among them was Dionysius, a member of the Areopagus, also a woman named Damaris, and a number of others.

Acts 17:22–33, NIV

Paul’s approach was to start his teaching from the vantage point of the learner and stimulate their interest by informing them that he could tell them the identity of the unknown god. He hooked them, motivating them to listen. Then Paul shared the truth about God and his desire for a personal relationship with them. He proclaimed the truth about Jesus Christ and his resurrection as the way to enter into that relationship. After sharing the truth, Paul led his audience to consider how this truth was meaningful for all persons everywhere and that the entire world needed to repent. Finally, Paul focused on personal application. We know this because some wanted to hear him again, and others chose to believe and follow Christ.[13]

The HBLT method includes these four key steps of motivation, examination, life application, and personal application. They are designed as four distinct parts of a session, each with a different purpose, but in reality, they should flow together in one seamless plan, and the learners shouldn’t be aware when one part ends and another begins. However, before you begin writing each component of an HBLT plan, you must determine the overall purpose of the unit of study you are creating and identify the specific goals and indicators for each session. You can refer to your curriculum plan to select the topic or subtopics and the associated goals and indicators you identified. Create a template or outline for the entire unit, including the following elements:

- Unit Subject and Title (identify the focal topic or subtopic from your curriculum plan)

- Unit Goal

- Age Group of Target Audience

- Session Topic/Subtopic 1 and Title

- Key Scripture Focus

- Exegetical Idea (the big idea of the biblical passage)

- Pedagogical Idea (the main concept or idea you want the students to learn; the takeaway for the session)

- Learning Goal and Indicator

- List of Needed Materials or Supplies for the Session

- Preparation List (describe any special things the teacher will need to do ahead of time, such as a special room arrangement, queuing up a video clip, making photocopies, etc.)

- List of Learning Activities for the Hook, Book, Look, and Took in Order (include an estimated time frame for each section to help the teacher in planning; these must be written in detail in the plan so that anyone could teach the session from this written document)

- Closing Challenge and Prayer

- Session Outline Repetition for Each of the Subsequent Sessions

Reflection Exercise

- Review your curriculum plan and select one of your topics for developing a unit of study. Each of the subtopics may be used for individual sessions. Plan on a four-session unit.

- Using the template, create an outline for your unit.

Designing HBLT Learning Activities

Each part of the HBLT plan is designed for a specific purpose, but none is limited to one single activity. While a small group discussion-based approach to teaching relies on verbal learning techniques, the HBLT approach to teaching and learning allows for many different techniques and methods, making it an ideal way to connect with students with a variety of learning styles. The hook is introductory and, in a typical one-hour session, should probably not take longer than ten minutes to complete and transition to the book. The book represents an exploration and study of the content, the foundational biblical concepts and truths you want your students to understand and value, so this portion of the lesson should be significant in terms of time allowed. Twenty to twenty-five minutes is a good consideration as you plan. Both the look and the took are significant, but ten to fifteen minutes is often sufficient for each of these if only an hour is dedicated for the entire session. Keep in mind that this doesn’t account for any additional activities a group may engage in when they meet. If there are announcements, a separate time of worship, or refreshments or games included, this time must be factored into the planning process. It is hard to imagine how effective discipleship could take place if less than one full hour of focused group study takes place on a weekly basis.

The hook is designed to motivate students to learn and to stimulate their curiosity by connecting the subject with their personal needs. When learners believe that a session is relevant to their lives, they are more likely to want to participate and be involved. This requires teachers to know their learners. The focus in chapter 3 of this book was on understanding the audience. This will be helpful as you are designing your lesson plans, but additional effort will be required on the part of the teacher to develop personal relationships with those in the group.

A good hook sets the focus for the session and should include a natural transition from that learning activity to the subject or biblical content of the study. In designing the hook, refer to chapter 5, which describes principles of learning for knowledge, understanding, and affective learning. These guidelines can help you think about the types of learning experiences that will be most relevant to your goal. Then refer to the various techniques and methods described previously in this chapter to stimulate your thinking and help you design a learning activity that will pique the interest of your learners and motivate them to participate fully. An effective hook could be a discussion about a current event related to the study, a poignant question, an object lesson, a media clip, or even a short game. The key is to make sure the activity hooks the learner and isn’t simply an irrelevant icebreaker. The hook is part of the lesson and should lead toward learning and growth. Include a transitional statement at the close of the hook that connects this motivational exercise to the overall purpose and focus of the session.

The book portion of a lesson plan is examination, focusing on a deep study of the passage or biblical truths. This requires an accurate understanding of the Scripture under consideration. To accurately plan for the book, it is necessary to have done a prior in-depth biblical study. Deductive studies begin with a topic and use Scripture to illustrate or illuminate the topic so that it is dealt with in a manner that is biblically accurate. Inductive studies focus primarily on a study of Scripture and allow the topics or content to be derived from the text. Discipleship sessions may take either form, but regardless, a comprehensive study of the passage or passages is necessary. A guide for completing an inductive study is included in chapters 4 and 5 in Creative Bible Teaching by Richards and Bredfeldt. Another excellent resource for preparing to teach is Effective Bible Teaching by James C. Wilhoit and Leland Ryken.

The key components of an inductive Bible study are observation, interpretation, generalization, application, and implementation. Observation includes an understanding of who authored a text, when, and for what purpose. It examines the type of literature represented by the passage as well as the structure of the text. Interpretation involves a careful study of the meaning and significance of the passage. It takes into account the continuity of the message as it relates to the totality of Scripture and considers both the context and customary meaning of the passage. Generalization focuses on the big idea of the passage, answering such questions as, What is the author talking about, what is he saying about the subject, and what is the key transferable idea of the passage to life today? The answers to these questions form the exegetical idea for a lesson when summarized into one concise statement of truth. Application in an inductive study is a means of discovering biblical answers to common problems. When studying a passage, it is important to answer the following questions: Is there a teaching here to be learned and followed? Does the passage contain a rebuke or a correction to be heard and obeyed? In what way does the passage train us to be righteous? Implementation is the final part of a study, when the learner is challenged to appropriate personal meaning. This may include identifying the need for personal change, considering how best to make those changes, and asking God for the power to implement the changes the Holy Spirit has revealed to them through the study.[14]

One common mistake that teachers make is to substitute an inductive study for a lesson plan. Often, teachers simply lecture over the background and meaning of a passage and fail to involve the learners in active learning or personal application of the text. While the inductive study includes elements of both examination and application, it is not intended as a substitute for a well-designed group lesson plan. Effective lesson plans rely on comprehensive biblical studies to formulate the content for the book portion of their resources. They are most effective, however, when students engage in active learning and are led to discover biblical significance instead of being told why Scripture matters.

The look portion of a lesson is focused on helping learners understand how the biblical content relates to life today in their culture. It allows them to connect biblical teachings to daily life and understand their relevance in contemporary society. One of the most effective means of doing this is to incorporate case studies or current events. This may be done using a variety of techniques. Learners may be asked to analyze trending shows or the lyrics of popular music. They may use their biblical understanding to propose solutions for current cultural difficulties or evaluate the actions of celebrities or public policies according to what they have learned. Art, drama, or creative writing may be appropriate methods for discovering life applications.

The final part of the HBLT method is the took. This is where personal spiritual transformation is prompted. Lasting change won’t take place within one discipleship session, but the took asks students to begin considering where change is needed in their own lives. It goes beyond an understanding of how the content is generally relevant or applicable. It prompts students to think about areas where they are in need of personal growth. They should have a clear understanding of how the study relates to their lives. It might prompt them to think about changes, such as starting or stopping a behavior. This could involve a personal inventory for them to complete and reflect on their responses. It might ask them to write a letter to someone and seek their forgiveness. Students might be asked to create a personal plan for incorporating a particular spiritual discipline into their lives. Consider your learners as you design meaningful ways for them to begin the process of appropriating what they have learned through the session.

One final consideration for your teaching plan involves determining whether you have included an opportunity for the indicator to be achieved. Remember that the indicator’s purpose is to determine whether the goal has been met. It is useless, however, to determine the evidence needed to prove the achievement of a goal if you never ask for that evidence within your study. At least one of the learning activities should provide an opportunity for the learners to accomplish the indicator. This is often found within the look or the took. It is known as a test because it is a means of testing the accomplishment of the goal.

The test activity should match the indicator in three key ways. It should require the learner to use the same or a similar form of response. If it is a verbal indicator, then the test activity should be verbal. If it is discriminatory, then it should require discrimination. The test activity should also relate to the same content. This is more precise than expecting them to relate to the same subject. Content is a more narrow, specific part of a broader subject. For example, cooking is a subject, but grilling steaks and boiling potatoes are not the same content. Both the indicator and test activity should focus on the same content related to the subject. The final characteristic of a test activity is that it should be at the same level of learning as the indicator. For example, if the indicator calls for application, an appropriate test item would not require the student to synthesize.

Reflection Exercise

- Select three of the goals and indicators you completed for chapter 6. Write a test learning activity for each one. Make sure that your test and indicator match in all three of the key areas: form, content, and level of learning.

- Using the template, create an outline for your unit.

Lesson plans should reflect a variety of methods and appeal to all types of learners through at least one of the activities. Each part of the lesson may include more than one learning activity, but they should build on one another and be presented in a logical order. You may want to number each activity to provide clarity for whoever is going to be teaching. Care should be taken so the session doesn’t become a jumble of disparate activities, but every learner should be able to leave a class with the sense that they have gained something important and relevant for their lives. As you write your plans, focus on balancing your techniques and approaches. Use precise, direct, active verbs that will help potential leaders visualize the action you are calling for in your goal, indicator, or activity. Give enough detail for the reader to know exactly how to do what you are asking them to do. Make sure your learning activities and the methods you suggest can actually be accomplished during the time frame you have established. Proofread what you have written and get rid of ambivalent or vague language that can mean different things to different people.

Significant Concepts

deductive studies

hook, book, look, took

inductive studies

interpretation

learning styles

motivation, examination, life application, personal application

observation, interpretation, generalization, application, implementation

test activity

Putting It All Together: Chapter Assignment

Using the unit template you created for a previous Reflection Exercise, select one of the sessions and write a complete HBLT lesson plan. Include each element of the plan, incorporating various techniques and methods to accomplish your goal and appeal to a variety of learners. Refer to the learning principles from chapter 5 as you design your activities. Don’t forget to include a test activity in your plan that mirrors your indicator. Remember that each portion of the plan may use more than one activity, but the session should have a flow. The learners should not feel as if they have jumped through hoops or bounced from one activity to the next but should experience a seamless time of learning that is personally impactful.

- George Moss, “4 Historical Figures People Often Misunderstand,” Oxford Open Learning, May 2, 2024, https://www.ool.co.uk/a-level-3/4-historical-figures-people-often-misunderstand. ↵

- “The Roman Empire in the First Century: Cleopatra & Egypt,” PBS, 2006, https://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/cleopatra.html#:~:text=A%20final%20solution,three%2Dquarters%20of%20their%20fleet. ↵

- “Beethoven Biography,” Biography Online, accessed January 30, 2025, https://www.biographyonline.net/music/beethoven.html. ↵

- “Vincent Van Gogh Biography,” Biography Online, accessed January 30, 2025, https://www.biographyonline.net/artists/vincent-van-gogh.html. ↵

- Cynthia Ulrich Tobias, The Way They Learn (Colorado Springs: Focus on the Family, 1994), 104–5. ↵

- Karen Jones, “Multiple Intelligences and Learning Styles,” in Teaching the Next Generations, ed. Terry Linhart (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), 86–99. ↵

- Rita Dunn, “Rita Dunn Answers Questions on Learning Styles,” Educational Leadership, October 1990, 15–19. ↵

- Rita Dunn and Shirley A. Griggs, Learning Styles: Quiet Revolution in American Secondary Schools (Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals, 1988), 3. ↵

- Jones, “Multiple Intelligences.” ↵

- Lois LeBar, Education That Is Christian (Old Tappan, NJ: Fleming H. Revell, 1953), 208, 215–16. ↵

- Michael Novelli, Shaped by the Story: Discover the Art of Bible Storying (Minneapolis: Sparkhouse, 2013). ↵

- LeBar, Education, 229. ↵

- Lawrence O. Richards and Gary J. Bredfeldt, Creative Bible Teaching (Chicago: Moody Press, 2020), 169–70. ↵

- Richards and Bredfeldt, Creative Bible Teaching, 68–78. ↵